Abstract

Background

Cancer patients are particularly vulnerable to COVID-19, partially owing to their compromised immune systems and curbed or cut cancer healthcare services caused by the pandemic. As a result, cancer caregivers may have to shoulder triple crises: the COVID-19 pandemic, pronounced healthcare needs from the patient, and elevated need for care from within. While technology-based health interventions have the potential to address unique challenges cancer caregivers face amid COVID-19, limited insights are available. Thus, to bridge this gap, we aim to identify technology-based interventions designed for cancer caregivers and report the characteristics and effects of these interventions concerning cancer caregivers' distinctive challenges amid COVID-19.

Methods

A systematic search of the literature will be conducted in PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Scopus from the database inception to the end of March 2021. Articles that center on technology-based interventions for cancer caregivers will be included in the review. The search strategy will be developed in consultation with an academic librarian who is experienced in systematic review studies. Titles, abstracts, and full-text articles will be screened against eligibility criteria developed a priori. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses procedures will be followed for the reporting process.

Conclusions

COVID-19 has upended cancer care as we know it. Findings of this study can shed light on evidence-based and practical solutions cancer caregivers can utilize to mitigate the unique challenges they face amid COVID-19. Furthermore, results of this study will also offer valuable insights for researchers who aim to develop interventions for cancer caregivers in the context of COVID-19. In addition, we also expect to be able to identify areas for improvement that need to be addressed in order for health experts to more adequately help cancer caregivers weather the storm of global health crises like COVID-19 and beyond.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42020196301

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A growing body of research is exploring the impact of COVID-19 on cancer care and management [1,2,3]. Already acknowledged as being infectious and deadly [4, 5], as of 8 January 22nd, 2021, there are approximately 96.2 million confirmed COVID-19 cases, among which, 2.06 million deaths have already occurred [6]. Through a retrospective analysis of 355 patients dying from the coronavirus, one in five of these patients had active cancer [7]. Individuals with cancer can experience underlying malignancy, treatment-induced immunosuppression, and possible comorbidity [8,9,10], and it has been shown that they are more likely to develop severe symptoms from COVID-19 [8, 9, 11]. Research also indicates that, compared to COVID-19 patients without cancer, COVID-19 patients with cancer are more likely to have higher risks in all severe outcomes (e.g., higher mortality rates) [8, 9]. Additional factors may further increase cancer patients' vulnerability to COVID-19, such as limited access to medical resources and cancer care, during this pandemic [12,13,14].

Due to medical resource rationing, many cancer care and treatment services were either canceled or indefinitely postponed during the early part of the COVID-19 pandemic [15, 16]. No longer having access to the healthcare services they were accustomed to or depended upon [11, 16], informal cancer caregivers may now be shouldering considerably more caregiver burden due to COVID-19. While the effects of this deprivation of access to cancer care on cancer patients are well discussed [17, 18], caregiving responsibilities influencing cancer caregivers’ health and well-being is less examined. Other than healthcare professionals in a caring role as a part of their work, an informal caregiver is generally offered unpaid or ill-compensated care to a family member or a friend, due to disease-centered or aging-related reasons. Pre-COVID-19 data show that caregivers shoulder approximately 70–89% of all care needed by patients in general [19]. Considering the interruptions COVID-19 exerts on cancer care and treatment, it is probable that cancer caregivers are shouldering even greater caregiving responsibilities for patients.

Cancer caregivers have been facing tremendous stressors during the COVID-19 pandemic. The range of issues resembles a triple crisis of (1) confronting the impact of the coronavirus outbreak, (2) shouldering pronounced care needs from the patient, and (3) coping with considerable needs for physical and psychological care from within. In other words, in addition to being forced to deal with a pandemic and patients’ pronounced cancer care needs discussed above, caregivers may also experience substantial physical and psychological health issues that require timely medical attention. Mounting evidence indicates that cancer caregivers often face considerable caregiver burden that can negatively impact their physical and psychosocial health [20,21,22]. In a review study, findings on 21,149 caregivers show that the prevalence of depression and anxiety is 42.30% and 46.55% in these caregivers, respectively [23]. It is important to note that blanket measures, such as lockdowns, self-isolation, and social distancing, can exert further pressure on cancer caregivers. Research suggests that social support from community members can lower anxiety and depression experienced by cancer caregivers; these supports are significantly limited due to social distancing recommendations [24].

Technology-based interventions refer to “the use of technology to manage or support health promotion strategies aiming to produce accessible and affordable health solutions to the target audience” [25]. Studies have shown that technologies (e.g., telehealth) may be beneficial to address issues cancer caregivers experienced during COVID-19; with some research identifying the potential improvement to health and well-being [26,27,28]. Technology-based interventions can offer greater accessibility to care for cancer caregivers that can be (1) delivered remotely without physical contacts between interventionists and the caregivers [29, 30], (2) received cost-effectively without the need for transportation [27], and accessed conveniently with self-paced learning [31, 32] of tailored content [33, 34]. In addressing the unique challenges cancer caregivers face amidst COVID-19, no research has identified technology-based health solutions for cancer patients that can address these needs, such as care needs, general healthcare needs, information and communication needs, and social support needs (see Table 1). Thus, to bridge this gap, this systematic review identifies the literature surrounding technology-based solutions for cancer caregivers that can mitigate challenges they face amid COVID-19.

Methods

Study registration and protocol

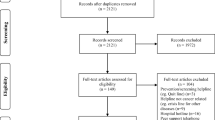

This review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews or PROSPERO (CRD42020196301). We will also follow the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) in our research procedures [35] to further safeguard research rigor.

Search strategy

The following databases will be searched for potential articles: PubMed, PsycINFO CINAHL, and Scopus. The search will be limited to original articles published in English from the database inception to the end of March 2021. Searches incorporated medical subject heading (MeSH) and keyword terms in three categories: cancer, caregivers, and technology platforms. Our search strategy will be developed in consultation with an academic librarian experienced in systematic review studies to ensure research rigor. Snowballing (manual searching reference lists) of included studies will be conducted to obtain additional eligible articles. Furthermore, reverse tracing potential eligible manuscripts that cited included papers will be administered via Google Scholar. An example search string is listed in Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

In the context of this study, caregivers are defined as patients’ family or friends who may offer mostly long-term care to patients, often with little or no financial compensation of any form. This paper broadly defines interventions as stimuli or mechanisms that are aimed to produce changes in outcome variables (e.g., self-care abilities increased). Studies will be included if they are published in English, have relevant information on technology-based interventions for cancer caregiving, and with detailed inclusion criteria listed in Table 3. Ensuring data quality, comments, editorials, gray literature, and reviews will be excluded from the review. Overall, articles will be excluded if they (1) did not include a cancer caregiver population, (2) did not provide information on intervention, and (3) did not describe how technology is integrated into the intervention strategy.

Selection of studies and data extraction

Search results will be managed using Rayyan [36], a free web application that allows sorting and storing articles will be used to remove duplicate records and screen articles. Both two phrases of screening, title-abstract screening and full-text screening, will be conducted by two primary reviewers (ZS and XL) independently. Discrepancies will be solved by consensus, and when needed, with input from the rest of the research team. Data will be extracted independently by the reviewers (ZS and XL) based on the research aim and selection criteria adopted in this study. Specifically, for studies that met the inclusion criteria, the primary reviewers (ZS and XL) will extract the following information from the final included studies: study and participant characteristics (e.g., study aim), intervention characteristics (e.g., the use of technology in interventions), and details on study outcomes (e.g., intervention outcomes).

Data synthesis and analysis

If eligible studies are found to be heterogeneous, we will conduct a narrative synthesis instead, as opposed to a meta-analysis, to summarize key insights from the data. A summary of the key information extracted will be utilized to synthesize the main research findings. Descriptive analysis will be performed on categorical variables. If there are enough similarities in eligible papers to be pooled, a meta-analysis will be conducted to obtain further insights from the data. The Cochrane's Q test and I2 test will be adopted to calculate heterogeneity within studies—I2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75% suggest low, medium, and high heterogeneity, respectively [37]. If much heterogeneity is present, random-effect models will be adopted (as opposed to fixed-effect models), as these models are more robust in detecting large variations in studies [38]. Review manager 5.3 (Cochrane Collaboration software) will be utilized to conduct the random effect model. Visual inspection of funnel plots will be used to evaluate publication bias if needed. If enough data are available for meaningful investigation (e.g., theoretically or clinically meaningful), subgroup analyses will be conducted for diverse types of cancer types, stages, interventions, follow-up duration, caregiver types, and country. A sensitivity analysis will be conducted by sequentially removing one study periodically and reanalyzing the data to evaluate the impact of individual studies on overall outcomes. This process will allow potentially methodologically flawed research included in the review; a study will be considered acceptable if it affects the meta-estimate of less than ± 5%.

Risk of bias and quality of evidence

The Cochrane Collaboration evaluation framework will be utilized to investigate the risk of bias of articles that met the inclusion criteria, including selection, performance, detection, attrition, reporting, and other biases [39]. The framework has seven domains: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and any other source of bias. Two primary reviewers (ZS and XL) will evaluate the included articles’ quality independently, and give the articles a score (high, medium, or low) based on results of the evaluation. These reviewers will also independently adopt the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) framework to assess the overall quality of evidence of the eligible articles. The GRADE guideline has five domains: risk of bias, indirectness, inconsistency, imprecision, and publication bias [40]. Any discrepancies will be resolved via group discussions till a consensus is reached.

Discussion

COVID-19 has upended cancer care as we know it [41,42,43,44,45]. Evidence shows that pandemics of COVID-19’s scale could be particularly deadly to vulnerable populations such as cancer patients [2, 3, 8,9,10, 46]. Furthermore, COVID-19 prevention mechanisms, such as lockdowns, self-isolation, and social distancing measures, as well as COVID-19-induced medical resources rationing, have curbed or cut cancer patients and their caregivers’ access to traditional healthcare services [47,48,49,50]. Not to mention chaos and consequences associated with pandemic information overload, COVID-19 infodemics, and dysfunctional vaccine dissemination may further compound cancer patients and their caregivers’ interaction with the ever-increasingly overstretched and overstressed healthcare systems [51,52,53]. As a result, cancer caregivers often have to step up to address patients’ healthcare needs and wants [42, 54,55,56,57], which, in turn, could exert substantial mental and physical stress on informal caregivers, above and beyond COVID-19-related burdens the general public shoulders daily [20,21,22]. Technology-based health solutions can bypass spatial distancing constraints caused by COVID-19 and have the ability to address unique challenges cancer patients, and their caregivers face amid COVID-19 [58,59,60,61].

As the frontline physician among us observed, the most challenging cancer care component during COVID-19 is how to resume cancer treatment for patients [1]. Because the pandemic has caused severe limitations to access to cancer care and availability of transportation, across the world, many patients, even in severe conditions, had to suspend their treatment plans [1, 56, 62]. Take Chinese cancer patients, for instance. The pandemic occurred during the Chinese traditional spring festival. As a result, a large number of cancer patients traveled home with their caregivers for their extended-family reunion. However, due to the outbreak [63], after the spring festival, most of them were under lockdown at their hometown or somewhere in between, without access to critical cancer care and treatment options. Even among patients and caregivers who managed to rush back to the hospital for their treatments, they had to be self-quarantined for 14 days and then undergo a series of tests. Technologies, such as the “Health Code”, a digital color-coded health system that allows the governments and health agencies to track cell phone location to better determine individuals’ whereabouts (i.e., whether they have recently traveled to places witnessed severe COVID-19 outbreaks) [64], undoubtedly have helped expedite the information processing speed, and saved valuable time these patients and caregivers desperately needed.

However, while useful insights are available in the literature, there is a dearth of research that can shed light on evidence-based and practical health solutions cancer caregivers can use to address and alleviate unique challenges they face during COVID-19 or any future disease pandemics. Therefore, to bridge this gap, we aim to identify technology-based interventions designed for cancer caregivers and report the characteristics and effects of these interventions concerning the distinctive challenges cancer caregivers face amid COVID-19. Additionally, this paper will present practical insights into the diverse intervention approaches that can help deliver digital health solutions for cancer caregivers amid and beyond COVID-19. Furthermore, this study’s results can also offer valuable insights for researchers who aim to develop interventions for cancer caregivers in the context of COVID-19. In addition, it is also expected to identify areas for improvement that need to be addressed in order for health experts to more adequately help cancer caregivers weather the storm of global health crises like COVID-19 and beyond.

Availability of data and materials

None

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PROSPERO:

-

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

References

Cancino RS, et al. The Impact of COVID-19 on Cancer Screening: Challenges and Opportunities. JMIR Cancer. 2020;6(2):e21697.

Robilotti EV, Babady NE, Mead PA, Rolling T, Perez-Johnston R, Bernardes M, Bogler Y, Caldararo M, Figueroa CJ, Glickman MS, Joanow A, Kaltsas A, Lee YJ, Lucca A, Mariano A, Morjaria S, Nawar T, Papanicolaou GA, Predmore J, Redelman-Sidi G, Schmidt E, Seo SK, Sepkowitz K, Shah MK, Wolchok JD, Hohl TM, Taur Y, Kamboj M. Determinants of COVID-19 disease severity in patients with cancer. Nat Med. 2020;26(8):1218–23.

Wang Y, Duan Z, Ma Z, Mao Y, Li X, Wilson A, Qin H, Ou J, Peng K, Zhou F, Li C, Liu Z, Chen R. Epidemiology of mental health problems among patients with cancer during COVID-19 pandemic. Transl Psychiat. 2020;10(1).

Jordan RE, Adab P, Cheng KK. Covid-19: Risk factors for severe disease and death. BMJ. 2020;368:m1198.

Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239–42.

Johns Hopkins University. The COVID-19 global map. 2020 [cited 2021 January 8]; Available from: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html.

Onder G, Rezza G, Brusaferro S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1775–6.

Mehta V, et al. Case fatality rate of cancer patients with COVID-19 in a New York hospital system. Cancer Discov. 2020:CD-20-0516.

Dai M, et al. Patients with cancer appear more vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2: A multicenter study during the COVID-19 outbreak. Cancer Discov. 2020;10(6):783.

Zhang, L., et al., Clinical characteristics of COVID-19-infected cancer patients: A retrospective case study in three hospitals within Wuhan, China. Annals of Oncology, 2020.

Sidaway P. COVID-19 and cancer: What we know so far. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020;17(6):336.

Gray DM, et al. COVID-19 and the other pandemic: Populations made vulnerable by systemic inequity. Nat Rev. 2020.

Saini KS, et al. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer treatment and research. The Lancet. Haematology. 2020;7(6):e432–5.

Segelov E, et al. Practical considerations for treating patients with cancer in the COVID-19 pandemic. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020:OP.20.00229.

Kutikov A, et al. A war on two fronts: cancer care in the time of COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(11):756–8.

CovidSurg Collaborative, D. Nepogodiev, and A. Bhangu, Elective surgery cancellations due to the COVID-19 pandemic: Global predictive modelling to inform surgical recovery plans. BJS (British Journal of Surgery), 2020. n/a(n/a).

Xia Y, et al. Risk of COVID-19 for patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(4):e180.

Romeo A, Castelli L, Franco P. The impact of COVID-19 on radiation oncology professionals and cancer patients: From trauma to psychological growth. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2020.

Hsu T, et al. Understanding caregiver quality of life in caregivers of hospitalized older adults with cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(5):978–86.

Bevans M, Sternberg EM. Caregiving burden, stress, and health effects among family caregivers of adult cancer patients. JAMA. 2012;307(4):398–403.

Charalambous A, et al. Cancer-related fatigue and sleep deficiency in cancer care continuum: concepts, assessment, clusters, and management. Supp Care Cancer. 2019;27(7):2747–53.

He Y, et al, Sleep quality, anxiety and depression in advanced lung cancer: Patients and caregivers. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2020.

Geng H-M, et al. Prevalence and determinants of depression in caregivers of cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2018;97(39):e11863.

García-Torres F, et al. Social support as predictor of anxiety and depression in cancer caregivers six months after cancer diagnosis: A longitudinal study. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(5-6):996–1002.

Su Z, et al. Understanding technology-based interventions for caregivers of cancer patients: A systematic review-based concept analysis. J Med Int Res. 2020.

Carrion-Plaza A, Jaen J, Montoya-Castilla I. HabitApp: New Play Technologies in Pediatric Cancer to Improve the Psychosocial State of Patients and Caregivers. Frontiers in psychology. 2020;11:157. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00157. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7020696/.

Wang J, et al. Mhealth supportive care intervention for parents of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: quasi-experimental pre- and postdesign study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018.

Duggleby W, et al, Feasibility study of an online intervention to support male spouses of women with breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2017.

Kubo A, Kurtovich E, McGinnis M, Aghaee S, Altschuler A, Quesenberry C Jr, Kolevska T, Avins AL. A Randomized Controlled Trial of mHealth Mindfulness Intervention for Cancer Patients and Informal Cancer Caregivers: A Feasibility Study Within an Integrated Health Care Delivery System. Integr Cancer Ther. 2019;18:1534735419850634. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534735419850634. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31092044/.

Kubo A, Altschuler A, Kurtovich E, Hendlish S, Laurent CA, Kolevska T, Li Y, Avins A. A Pilot Mobile-based Mindfulness Intervention for Cancer Patients and their Informal Caregivers. Mindfulness (NY). 2018;9(6):1885–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0931-2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30740187/. Epub 24 Mar 2018.

Mosher CE, Winger JG, Hanna N, Jalal SI, Einhorn LH, Birdas TJ, Ceppa DP, Kesler KA, Schmitt J, Kashy DA, Champion VL. Randomized Pilot Trial of a Telephone Symptom Management Intervention for Symptomatic Lung Cancer Patients and Their Family Caregivers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;52(4):469–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.04.006. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27401514/. Epub 2016 Jul 9.

Dionne-Odom JN, et al. Family caregiver depressive symptom and grief outcomes from the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symp Manag. 2016;52:378–85.

DuBenske LL, et al. CHESS improves cancer caregivers' burden and mood: Results of an eHealth RCT. Health Psychol. 2014;33(10):1261–72.

Santin O, et al. Using a six-step co-design model to develop and test a peer-led web-based resource (PLWR) to support informal carers of cancer patients. Psycho-Oncol. 2019;28(3):518–24.

Moher D, et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5:210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4.

Higgins JP, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928.

Cooper H, Hedges LV, Valentine JC. The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2009.

Higgins JP, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. John Wiley & Sons; 2019.

Balshem H, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):401–6.

Zhen H, et al. COVID-19 outbreak and cancer patient management: Viewpoint from radio-oncologists. Radiother Oncol. 2020: p. S0167-S8140(20)30206-1.

Baddour K, et al. Potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on financial toxicity in cancer survivors. Head Neck. 2020;42(6):1332–8.

Brunetti O, et al. COVID-19 infection in cancer patients: How can oncologists deal with these patients? Front Oncol. 2020;10:734.

De Vincentiis L, et al. Cancer diagnostic rates during the 2020 ‘lockdown’, due to COVID-19 pandemic, compared with the 2018–2019: An audit study from cellular pathology. J Clin Pathol. 2020: p. jclinpath-2020-206833.

Calabrò L, et al. Challenges in lung cancer therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(6):542–4.

Su Z, McDonnell D, Li Y. Why is COVID-19 more deadly to nursing home residents?. QJM: Int J Med. 2021.

Farrell TW, et al. Rationing limited healthcare resources in the COVID-19 era and beyond: ethical considerations regarding older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(6):1143–9.

Smrke A, et al. Telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic: impact on care for rare cancers. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:1046–51.

Kuderer NM, Choueiri TK, Shah DP, Shyr Y, Rubinstein SM, Rivera DR, ... West J. Clinical impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer (CCC19): a cohort study. The Lancet. 2020;395(10241):1907–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31187-9. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)31187-9/fulltext.

van de Haar J, Hoes LR, Coles CE, et al. Caring for patients with cancer in the COVID-19 era. Nat Med. 2020;26:665–71. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0874-8.

Su Z, Wen J, Abbas J, McDonnell D, Cheshmehzangi A, Li X, Ahmad J, Šegalo S, Maestro D, Cai Y. A race for a better understanding of COVID-19 vaccine non-adopters. Brain Behav Immun Health. 2020;9:100159.

Su Z, McDonnell D, Wen J, Kozak M, Abbas J, Šegalo S, Li X, Ahmad J, Cheshmehzangi A, Cai Y, Yang L, Xiang YT. Mental health consequences of COVID-19 media coverage: the need for effective crisis communication practices. Glob Health. 2021;17(1).

Su Z, Wen J, McDonnell D, Goh E, Li X, Šegalo S, Ahmad J, Cheshmehzangi A, Xiang YT. Vaccines are not yet a silver bullet: The imperative of continued communication about the importance of COVID-19 safety measures. Brain Behav Immun Health. 2021;100204.

Guo Q, et al. Immediate psychological distress in quarantined patients with COVID-19 and its association with peripheral inflammation: A mixed-method study. Brain Behav Immun. 2020: p. S0889-S1591(20)30618-8.

Sher L. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide rates. QJM: Int J Med. 2020.

Young AM, et al. Uncertainty upon uncertainty: Supportive care for cancer and COVID-19. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2020;28(9):4001–4.

Laughlin AI, et al. Accelerating the delivery of cancer care at home during the Covid-19 pandemic. NEJM Catalyst Innov Care Deliv. 2020;1(4). https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/cat.20.0258#.

Keshvardoost, S., K. Bahaadinbeigy, and F. Fatehi, Role of telehealth in the management of COVID-19: Lessons learned from previous SARS, MERS, and Ebola outbreaks. Telemedicine and e-Health, 2020.

Al-Shamsi HO, et al. A practical approach to the management of cancer patients during the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic: An international collaborative group. Oncologist. 2020;25(6):e936–45.

Nguyen NP, Vinh-Hung V, Baumert B, Zamagni A, Arenas M, Motta M, ... Thariat J.. Older Cancer Patients during the COVID-19 Epidemic: Practice Proposal of the International Geriatric Radiotherapy Group. Cancers. 2020;12(5):1287. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12051287. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7281232/.

Lonergan PE, et al. Rapid utilization of telehealth in a comprehensive cancer center as a response to COVID-19: Cross-sectional analysis. J Med Int Res. 2020;22(7):e19322.

Mohile S, et al. Perspectives from the cancer and aging research group: caring for the vulnerable older patient with cancer and their caregivers during the COVID-19 crisis in the United States. J Geriatr Oncol. 2020;11(5):753–60.

Chen S, et al. COVID-19 control in China during mass population movements at New Year. The Lancet. 2020;395(10226):764–6.

Pan XB, Application of personal-oriented digital technology in preventing transmission of COVID-19, China. Ir J Med Sci (1971 -). 2020.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their gratitude to Emme Lopez, the academic librarian who helped with finalizing the search strategy. Gratitude also goes to the editors and reviewers for their constructive input.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZS developed the research idea and drafted the manuscript. DMD, BL, JK, XL, SS, SA, BEF, and JW reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:.

PRISMA-P checklist

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Su, Z., McDonnell, D., Liang, B. et al. Technology-based health solutions for cancer caregivers to better shoulder the impact of COVID-19: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev 10, 43 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01592-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01592-x