ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Depression contributes to disability and there are ethnic/racial disparities in access and outcomes of care. Quality improvement (QI) programs for depression in primary care improve outcomes relative to usual care, but health, social and other community-based service sectors also support clients in under-resourced communities. Little is known about effects on client outcomes of strategies to implement depression QI across diverse sectors.

OBJECTIVE

To compare the effectiveness of Community Engagement and Planning (CEP) and Resources for Services (RS) to implement depression QI on clients’ mental health-related quality of life (HRQL) and services use.

DESIGN

Matched programs from health, social and other service sectors were randomized to community engagement and planning (promoting inter-agency collaboration) or resources for services (individual program technical assistance plus outreach) to implement depression QI toolkits in Hollywood-Metro and South Los Angeles.

PARTICIPANTS

From 93 randomized programs, 4,440 clients were screened and of 1,322 depressed by the 8-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8) and providing contact information, 1,246 enrolled and 1,018 in 90 programs completed baseline or 6-month follow-up.

MEASURES

Self-reported mental HRQL and probable depression (primary), physical activity, employment, homelessness risk factors (secondary) and services use.

RESULTS

CEP was more effective than RS at improving mental HRQL, increasing physical activity and reducing homelessness risk factors, rate of behavioral health hospitalization and medication visits among specialty care users (i.e. psychiatrists, mental health providers) while increasing depression visits among users of primary care/public health for depression and users of faith-based and park programs (each p < 0.05). Employment, use of antidepressants, and total contacts were not significantly affected (each p > 0.05).

CONCLUSION

Community engagement to build a collaborative approach to implementing depression QI across diverse programs was more effective than resources for services for individual programs in improving mental HRQL, physical activity and homelessness risk factors, and shifted utilization away from hospitalizations and specialty medication visits toward primary care and other sectors, offering an expanded health-home model to address multiple disparities for depressed safety-net clients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Depressive symptoms and disorders are common in general populations and clients in healthcare settings, impact morbidity, and are priorities for comparative effectiveness research.1,2 Depression is prevalent across cultural groups, yet African Americans may have more severe depression.3 Ethnic minorities have worse access to depression care and worse outcomes in primary care than white patients.4 Evidence-based treatments include psychotherapies such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and antidepressant medication; but the latter has limited efficacy in mild depression.5,6 Some minority groups prefer psychotherapy,7 which is less available in under-resourced areas,8 where depressed adults suffer from medical and social problems and seek support from diverse service sectors. Quality improvement (QI) programs for depression that combine team leadership, care managers, clinician training, client education and system changes9 improve health outcomes relative to usual primary care.10 The Partners in Care study found greater improvement from QI relative to usual care for depressed African Americans and Latinos than for whites in primary care, while the IMPACT study found comparable benefits for minority and white depressed elderly.4,11,12 Despite recommendations to disseminate such programs,13 disparities persist,14 exacerbated in under-resourced communities by homelessness and other social determinants of health.4,15 Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is recommended to reduce disparities,16,17 and CBPR-based interventions can improve outcomes.18,19 CBPR studies confirm the importance of faith-based and community-based programs as partners to healthcare in addressing depression,20–22 but there are no studies of the added value of an expanded health-home model including such partners to address depression outcome disparities.

To address this gap, we developed a CBPR approach to depression in under-resourced communities in Los Angeles23 and used that experience to design Community Partners in Care (CPIC),24 which examines the value of a community engagement and planning (CEP) intervention over and above resources for services (RS) for individual programs to implement depression QI programs across healthcare and community-based service sectors. We hypothesized that CEP, through promoting uptake of QI across a strengthened network of diverse community-based agencies, would be more effective than RS or technical assistance to individual programs plus outreach, in improving clients’ mental health-related quality of life (HRQL) and reducing risk for probable depressive disorder, the study’s primary outcomes. Community members prioritized mental wellness, physical activity, employment and homelessness as outcomes and thought that CEP would shift case management to alternative sectors and improve the ability of social service providers to engage depressed clients in addressing housing. We expected CEP to increase services use relative to RS. This study reports intervention effects on 6-month client outcomes and services use. Future studies will address effects on providers, longer-term client outcomes, costs and mechanisms.

METHODS

Community Partners in Care (CPIC) is a group-level randomized comparative effectiveness trial of community engagement and planning across service sectors over and above resources for services for individual programs plus outreach to implement depression QI toolkits in under-resourced communities.

The study and community engagement intervention were implemented using Community-Partnered Participatory Research (CPPR),25 a form of CBPR that promotes equal authority of community and academic partners through trust building and two-way knowledge exchange. CPPR initiatives feature a council of academic and community members supporting partnered working groups and community forums for broad input.26 Goals and procedures, such as data ownership and handling of disputes are documented in written memoranda. Working groups develop and implement action plans following standard group rules of order and using community engagement activities to foster participation and equality in decision-making. CPPR initiatives have three stages: Vision (goals, concepts, approaches); Valley (main work and evaluation); and Victory (products and celebration).

The CPIC protocol, including changes in response to community input, is available at http://hss.semel.ucla.edu/documents/CPIC_Protocol_Dec2012.pdf. A supplemental appendix for this paper is available online.

Intervention Design

The CPIC Council modified depression QI toolkits4,27 supporting clinician assessment and medication management (manual and pocket cards), case management (manual), patient and education (brochure, video), and CBT (individual and group manuals) for use by diverse agencies, adding a lay health worker manual and team support tools28 from a post-disaster initiative blending QI toolkits8,12,29 (Table 1). The toolkits were available to programs online and through flash drives and hardcopy. The CPIC Council developed two interventions: 1) Resources for Services (RS) offered programs in each community technical assistance in toolkit use under a “train-the-trainer” paradigm through webinars plus site visits to primary care for each community. The trainers included a nurse care manager, licensed psychologist CBT trainer, three expert board-certified psychiatrists for medication management and QI, support staff and community service administrator to support participation and cultural competence. 2) Community Engagement and Planning (CEP) invited administrators to bi-weekly meetings for 5 months to build training capacity for toolkits and networks for services. Planning was co-led by community and academic Council members and followed principles of CPPR,25,26 such as equal authority for decisions and two-way knowledge exchange. CEP councils were provided with a workbook for developing written implementation plans tailored to the community and monitored plan implementation with course corrections as needed.

Within enrolled programs, providers could attend trainings and providers and clients could use intervention resources, even if not personally enrolled. Enrolled client lists were provided to CEP but not RS administrators, except one agency with a shared waiting room where both were given lists. Programs were not asked to limit toolkit use to enrolled clients.

Implementation

For RS, between December 2009 and July 2010 ten webinars were provided per community plus one make-up in one community; one primary care site accepted a visit. Khodyakov et al.49 describe CEP planning including development of trust and partnered co-leadership and completion of a written plan. Common features of plans included multiple training conferences, follow-up for individual programs and telephone and webinar supervision for therapists and case-managers, between December 2009 and July 2011. Los Angeles County’s Service Planning Area 6 (South LA) Council developed train-the-trainer capacities while the Service Planning Area 4 (Hollywood/Metro LA) Council used group case review to identify training modification needs. CEP offered more training and increased staff participation and total training hours relative to RS.

Sampling

The two communities, Los Angeles County Service Planning Areas 6 (South Los Angeles) (1.5 million people) and 4 (Hollywood-Metro Los Angeles) (500K people), have high rates of unemployment, homelessness, avoidable hospitalizations, and low rates of insurance.50 We hosted community meetings to determine service sectors viewed as important to depressed clients,24 and to identify vulnerable populations for oversampling. Across communities, sectors were mental health, primary care and public health, substance abuse, social services, and faith-based programs, parks, hair salons, and exercise clubs. South Los Angeles partners nominated substance abuse clients and African Americans and Hollywood-Metro homeless clients and seniors for over-sampling.

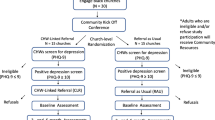

Program Recruitment and Randomization

With no standard approach to recruit diverse sectors, we used county lists supplemented by community nominations to identify agency names. We used an iterative process of contacting programs and assessing eligibility and interest to offer consent to 60 potentially eligible agencies having 194 programs, from which 133 potentially eligible programs (serving ≥ 15 clients per week, one or more staff, not focused on psychotic disorders or home services) were randomized (65 RS, 68 CEP) (Fig. 1). Within each community, programs were paired into exchangeable units or clusters of smaller programs, based on geographic location, service sector, size, population served, services provided, and funding streams; two larger agencies were their own stratum. One unit was randomized to CEP and the other to RS.51 Randomization was conducted by a statistician uninvolved with recruitment. Council members produced seed numbers for the randomization program.52 Site visits were conducted to finalize enrollment using recruiters blinded to assignment; 20 programs were ineligible, 18 refused and 95 programs from 50 consenting agencies enrolled (46 RS, 49 CEP; Fig. 1, Table 2). Administrators were informed of intervention status by letter. From census track data, participating and nonparticipating programs were comparable in age, sex, race, population density, and income at the zip code level (each p > 0.10).

Client Recruitment

After changes in response to community input, the study was designed to achieve a follow-up sample of 780 depressed clients, for a detectable effect size of 0.20–0.22 and percentage point difference between groups of 9.98–10.91 %, assuming power of 80 % with alpha = 0.05 (two-sided), and intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) = 0 .00–.02.51,53,54 To achieve this, we planned to enroll 557–600 clients per condition assuming 65–70 % retention.

Within programs, clients were screened in waiting rooms (consecutive) or events (random) from March 2010 to November 2010. Staff blinded to intervention status approached 4,649 adults (age ≥ 18) on 2–3 days per program and 4,440 (95.5 %) agreed to screening. Eligibility was limited to clients providing contact information and having at least mild depression (score ≥ 10 on the 8-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8), with the same scoring characteristics and cut-point as the PHQ-9.55 Based on community input we counted a response on either of two versions of one PHQ-8 item with and without the word “depression”; Pearson correlation coefficient of items was 0.99. Of 4,440 screened, 1,322 (29.8 %) were eligible and of these 1,246 (94.3 %) consented, a high rate for QI studies.10,12,29 Between April 2010 and January 2011, 981 (78.7 % of consented) completed baseline telephone surveys (interviewers blinded to assignment) and between November 2010 and August 2011, 759 completed 6-month follow-up telephone surveys (61.1 % of consented minus three deaths), a lower rate than some QI studies,27,29 but similar to studies of safety-net clients8,31; 1,018 (81.9 % of consented minus deaths) with baseline or follow-up data (Fig. 1) comprise the analytic sample. One RS and two CEP programs had no clients completing surveys, yielding 90 programs with clients in the analytic sample. The study, funded in 2007, was not considered a clinical trial by the National Institutes of Health and no data safety monitoring board was required; post data collection the study was registered (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01699789). No major design changes were made after recruitment began. Patients reporting recent suicidal ideation on surveys were contacted by telephone by a study clinician following a protocol. Procedures were approved by Human Subjects Protection Review Committees of RAND and participating agencies.

Measures

Baseline measures include program intervention assignment and sector and client data from the screener and baseline survey on demographics (age, sex), presence of three or more chronic conditions from 18 conditions, education level, race/ethnicity; from the 12-item Short Form health survey (SF-12)56 physical and mental health composite scores (PCS12, MCS12) and meeting federal family poverty criteria. Using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI),57 we assessed using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Psychiatric Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria 12-month major depressive or dysthymic disorder, current manic episode, recent anxiety disorder (1-month panic or post-traumatic stress or 6-month generalized anxiety disorder), and alcohol abuse or use of illicit drugs in 12 months. Study outcomes are based on client self-report at 6-month telephone follow-up. Pre-planned primary outcomes are poor mental HRQL (MCS12 ≤ 40, one standard deviation below population mean)56 and exceeding the cut-point for mild/moderate depression on the PHQ-955 (score ≥ 10). In response to community priorities, we developed indicators of mental wellness (three items of having in the prior 4 weeks some feeling of being calm or peaceful, having energy or being happy56); responding somewhat or definitely true to “my life is organized”58 as a resiliency measure; being at least fairly physically active from a single item; working for pay; missing work in the past 30 days; and either currently homeless/living in a shelter or having multiple risk factors for future homelessness,59,60 including no place to stay for at least two nights in the past 6 months or eviction from primary residence, financial crisis or food insecurity in the past 6 months from life events measures.61

We assessed services use in the past 6 months for overnight hospital stays for mental health or substance abuse, overnight substance abuse rehabilitation, emergency room (ER) visits, outpatient mental health or self/family groups visits, hotline calls, and use of outpatient primary care or public health clinics, substance abuse or social services programs, parks and community centers, and faith-based and other community locations, counting as depression-related visits for which the client reported receiving information, referral, counseling, or medication management for depression or emotional problems. We developed indicators for any use and being above the baseline median visits and counts of contacts. Since a single overnight stay could reflect emergency room use, we included for sensitivity analyses having ≥ four hospital nights. To account for potential bias in self-report, we asked participants to provide names and addresses for up to four providers per sector, and for high utilizers and “other” locations, confirmed sector assignment and feasibility of counts through internet searches and program telephone calls.

We conducted intent-to-treat, comparative-effectiveness analyses with intervention status as the independent variable, using logistic regression for dichotomous measures and log-linear models for counts. Consistent with group-randomized trial recommendations,51 we adjusted for baseline status of dependent variables and covariates (age, sex, ≥ three chronic conditions, education, race/ethnicity, family poverty, 12-month alcohol abuse or use of illicit drugs, 12-month depressive disorder, and community). We weighted data for 1,018 clients to characteristics of the eligible sample, with item-level imputation for missing data62,63 and wave-level64,65 imputation for missing surveys. Weights account for non-enrollment among eligible clients and attrition (see Supporting Online Material). All analyses were conducted using SUDAAN Version 10.0 (http://www.rti.org/sudaan/) and accounted for clustering (clients within programs),66 weighting, and multiple imputations.64 Significance of comparisons by intervention status was based on regression coefficients. Results of logistic regression models are presented as odds ratios (OR) and log-linear models as rate ratios (RR) with 95 % confidence intervals. We illustrate results for intervention groups adjusted for covariates using standardized predictions generated from fitted regression models.27,67 For outcomes, we provide adjusted differences in predictions with standard errors.68 We present Cohen’s effect size index h, defined for dichotomous variables,53 where h = 0.20 is small, h = 0.50 is medium and h = 0.80 is large. We supplement adjusted models with unadjusted raw data to assess robustness. We applied a Bonferroni adjustment69 considering two primary outcomes and compared the proportion of results across outcomes favoring one intervention to an assumed null-hypothesis of 0.5.

RESULTS

Baseline

Of 1,018 depressed clients, 57 % were female, 87 % were Latino and or African American; 43.6 % had less than a high school education, 73.6 % had income below poverty, 20 % worked and 54.1 % were uninsured. The percentage having 12-month depressive disorder was 61.9 %, while 39.3 % had substance abuse and 54.7 % had multiple chronic conditions. Over half had risk factors for homelessness. There were no significant differences by intervention status (Table 3).

Outcomes

Relative to RS, CEP reduced the percentage of clients having poor mental HRQL (primary) and overall poor mental health (confirmatory), with adjusted differences of seven percentage points. A similar trend for PHQ9 cut-point was not statistically significant; after Bonferroni adjustment for two primary outcomes, quality of life remains significant (p < 0.025). Community Priorities: CEP increased the percentage reporting mental wellness, an organized life, being physically active and reduced the percentage currently homeless or having multiple recent homelessness risk factors (each p < 0.05, adjusted differences from 8.98 to 12.27). There were no significant intervention differences in working or missing a workday (smallest p = 0.09). The direction favored CEP on all outcomes (Table 4). All effect size indices (Cohen’s h) were ≤ 0.25.

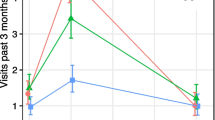

Utilization

The percentage of clients hospitalized for behavioral health was lower in CEP relative to RS (from 10.5 to 5.8 % [p < 0.05] [Table 5]), with a similar reduction for ≥ four nights. The percentage with two or more ER visits (baseline median) did not differ significantly by intervention status. CEP and RS clients had similar use of any specialty visit, but such CEP users had significantly fewer medication visits. The percentage with a primary care/public health depression visit did not differ significantly by intervention status, but such CEP users were more likely to have two or more depression visits (baseline median), adjusted difference of 17.9. There were no significant differences by interventions status in rates of visiting faith-based or park programs, but among users, CEP clients had significantly more depression visits. There were no significant differences by intervention status in use of substance abuse, social services or hotlines for depression (not shown), antidepressant medication use, healthcare counseling visits, or outpatient depression contacts. Findings were similar using raw data (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

This is to our knowledge the first study of the added value to clients’ health of community engagement and planning across sectors over and above resources for services for individual programs for implementing evidence-based depression QI across sectors in under-resourced communities. The collaborative model improved mental HRQL and mental wellness, physical activity and lowered an indicator of being homeless or having multiple risk factors for future homelessness. Outcomes improved in each condition, so RS may have been effective relative to no intervention, a hypothesis we cannot test. The standardized effect sizes were modest by conventional standards, but effects are based on a comparison of two active interventions, and progress in public health is often furthered by applying interventions of modest effect sizes to large populations. Actual effects, such as a seven percentage point reduction in poor quality of life or ten percentage point reduction in being homelessness or having multiple risk factors for future homelessness, seem meaningful in combination for a vulnerable sample. Further, program-level interventions may have affected clients beyond those enrolled, as resources were not limited to study clients. That the collaborative model had benefits spanning health and social determinants of health may have important implications for the design of health homes that activate community partners to co-manage depressed clients. Future research should determine whether intentional, two-way knowledge exchange in mental health and social competencies across healthcare and other community-based sectors further optimizes outcomes.

We found no significant intervention differences in use of antidepressants and healthcare counseling or in probable clinical depression. This may be because both conditions implemented depression QI; a stronger differential shift in treatment use is likely needed to shift depression status. Further, these findings suggest that the mechanism underlying outcome differences is not due to treatment exposure alone. Instead, we found shifts under CEP in depression services away from specialty medication visits toward primary care/public health, faith-based and park services, consistent with community members’ expectation for task shifting. An alternative explanation is that the intervention increased capacity of alternative sectors to engage depressed clients in addressing social determinants such as physical activity and housing. Future research is needed to clarify mechanisms by exploring linkages of system and provider changes to client outcomes and examine long-term outcomes and intervention costs.

In response to the unexpected finding of reduced behavioral health hospitalizations with CEP relative to RS, community partners suggested that patients were stabilized in sectors they already visited and had less need for hospitalization. The community engagement intervention, CPPR model on which it was based and QI toolkits are manualized,25,26 facilitating replication of this finding. CEP implementation required community engagement and trust building over several months and QI training co-led by community and clinical experts. Replication and sustainability may require infrastructure development, such as community-centered behavioral health homes with access to experts in QI for depression and community engagement. The toolkits, findings, and CPIC partners’ experience may support such efforts.

CPIC is one of the largest randomized trials of community engagement for health improvement in the United States, but has important limitations. The study was conducted in two communities where leaders had a history of applying CPPR to depression;20,23 most programs were new to this partnership. Response rates were moderate for agencies and high for programs. Most depression QI and participatory intervention studies use convenience samples of sites or integrated or government systems,4,8–10,18,19,22,27,29; our approach combined public lists and community recommendations to identify financially stable, safety-net programs, where task shifting for depression may be more effective.22 Client enrollment rates were high, but retention lower relative to some QI studies, but comparable to safety-net studies.31,70 Outcomes rely on client self-report at 6-month follow-up.

Overall, the study suggests that developing a collaborative network across healthcare and other community-based service sectors to implement evidence-based QI training for depression brings added value over and above resources for services plus outreach to individual programs, with benefits including mental HRQL, physical activity and reduced homelessness risk factors and behavioral health hospitalizations with shifts in outpatient services toward alternative sectors. While effect sizes are modest, in aggregate they appear meaningful for vulnerable groups that are difficult to stabilize. CEP may offer an approach to address multiple disparities for depressed clients through healthcare-community partnerships integrated by a common clinical QI model.

REFERENCES

Insel TR, Charney DS. Research on major depression. JAMA. 2003;289(23):3167–8.

Kessler R, Chiu W, Demler O, Merikangas K, Walters E. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617–27.

Williams DR, Gonzalez HM, Neighbors H, Nesse R, Abelson JM, Sweetman J, et al. Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites: results from the National Survey of American Life. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(3):305–15.

Miranda J, Duan N, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, Lagomasino I, Jackson-Triche M, et al. Improving care for minorities: can quality improvement interventions improve care and outcomes for depressed minorities? Results of a controlled randomized trial. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(2):613–30.

Schulberg HC, Raue PJ, Rollman BL. The effectiveness of psychotherapy in treating depressive disorders in primary care practice: clinical and cost perspectives. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2002;24(4):203–12.

Turner EH, Rosenthal R. Efficacy of antidepressants. BMJ. 2008;336(7643):516–7.

Dwight-Johnson M, Sherbourne CD, Liao D, Wells KB. Treatment preferences among depressed primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(8):527–34.

Miranda J, Chung JY, Green BL, Krupnick J, Siddique J, Revicki DA, et al. Treating depression in predominantly low-income young minority women. JAMA. 2003;290(1):57–65.

Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, Walker E, Simon GE, Bush T, et al. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines. JAMA. 1995;273(13):1026–31.

Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(21):2314.

Areán PA, Ayalon L, Hunkeler E, Lin EHB, Tang L, Harpole L, et al. Improving depression care for older, minority patients in primary care. Med Care. 2005;43(4):381.

Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, Ettner S, Buan N, Miranda J, et al. Five-year impact of quality improvement for depression: results of a group-level randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(4):378–86.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. New freedom commission on mental health: achieving the promise: transforming mental health in America. Final report. Rockville, MD: USDHHS; 2003. Report No.: SMA-03—3832.

Alegría M, Canino G, Ríos R, Vera M, Calderón J, Rusch D, et al. Inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among Latinos, African Americans, and non-Latino whites. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(12):1547–55.

Marmot MG, Wilkinson RG. Social determinants of health. USA: Oxford University Press; 2006.

Smedley BD, Syme SL. Promoting health: intervention strategies from social and behavioral research. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2000.

Thomas SB, Quinn SC, Butler J, Fryer CS, Garza MA. Toward a fourth generation of disparities research to achieve health equity. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:399–416.

Coppock DL, Desta S, Tezera S, Gebru G. Capacity building helps pastoral women transform impoverished communities in Ethiopia. Science. 2011;334(6061):1394–8.

Tripathy P, Nair N, Barnett S, Mahapatra R, Borghi J, Rath S, et al. Effect of a participatory intervention with women’s groups on birth outcomes and maternal depression in Jharkhand and Orissa, India: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9721):1182–92.

Chung B, Jones L, Jones A, Corbett C, Booker T, Wells K, et al. Using community arts events to enhance collective efficacy and community engagement to address depression in an African American community. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(2):237.

Dobransky-Fasiska D, Nowalk M, Pincus H, Castillo E, Lee B, Walnoha A, et al. Public-academic partnerships: improving depression care for disadvantaged adults by partnering with non-mental health agencies. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(2):110.

Patel V, Weiss HA, Chowdhary N, Naik S, Pednekar S, Chatterjee S, et al. Effectiveness of an intervention led by lay health counsellors for depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care in Goa, India (MANAS): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9758):18–31.

Bluthenthal R, Jones L, Fackler-Lowrie N, Ellison M, Booker T, Jones F, et al. Witness for Wellness: preliminary findings from a community-academic participatory research mental health initiative. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(Suppl):S18–34.

Chung B, Dixon EL, Miranda J, Wells K, Jones L. Using a community partnered participatory research approach to implement a randomized controlled trial: planning Community Partners in Care. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(3):780–95.

Jones L, Wells K. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. JAMA. 2007;297(4):407–10.

Jones L, Wells K, Norris K, Meade B, Koegel P. The vision, valley, and victory of community engagement. Ethn Dis. 2009;19(4 Suppl 6):S6.

Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, Duan N, Meredith L, Unützer J, et al. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care. JAMA. 2000;283(2):212.

Wennerstrom A, Vannoy SD, Allen C. Community-based participatory development of a community health worker mental health outreach role to extend collaborative care in post-Katrina New Orleans. Ethn Dis. 2011;21(Suppl 1):S1–45.

Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, Williams JW Jr, Hunkeler E, Harpole L, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting. JAMA. 2002;288(22):2836–45.

Hepner KA, Miranda JM, Woo SM, Watkins KE, Lagomasino IT, Wiseman SH, et al. Building recovery by improving goals, habits, and thoughts (BRIGHT): A group cognitive behavioral therapy for depression in clients with co-occurring alcohol and drug use problems-Group Leader’s Manual. Santa Monica, Calif: RAND Corporation; 2011.

Ell K, Xie B, Quon B, Quinn DI, Dwight-Johnson M, Lee PJ. Randomized controlled trial of collaborative care management of depression among low-income patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(27):4488–96.

Asarnow JR, Jaycox LH, Duan N, LaBorde AP, Rea MM, Murray P, et al. Effectiveness of a quality improvement intervention for adolescent depression in primary care clinics. JAMA. 2005;293(3):311–9.

Rubenstein LV. Improving Depression Outcomes in Primary Care: A User’s Guide to Implementing the Partners in Care Approach. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2000.

Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, Moody-Ayers S. Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;14(9):537–46.

Gamble VN. Under the shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and health care. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(11):1773–8.

Kataoka SH, Zhang L, Wells KB. Unmet need for mental health care among US children: variation by ethnicity and insurance status. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(9):1548–55.

Meredith LS, Mendel P, Pearson M, Wu SY, Joyce G, Straus JB, et al. Implementation and maintenance of quality improvement for treating depression in primary care. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(1):48–55.

Miller FG, Rosenstein DL. The therapeutic orientation to clinical trials. New Engl J Med. 2003;348(14):1383–6.

Rubenstein LV, Jackson-Triche M, Unutzer J, Miranda J, Minnium K, Pearson ML, et al. Evidence-based care for depression in managed primary care practices. Health Aff. 1999;18(5):89–105.

Schoenbaum M, Unützer J, Sherbourne C, Duan N, Rubenstein LV, Miranda J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of practice-initiated quality improvement for depression. JAMA. 2001;286(11):1325–30.

Sherbourne CD, Wells KB, Duan N, Miranda J, Unutzer J, Jaycox L, et al. Long-term effectiveness of disseminating quality improvement for depression in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(7):696.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mental health: culture, race, and ethnicity—a supplement to mental health: a report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: USDHHS; 2001.

UCLA-NPI/RAND Research Center on Managed Care for Psychiatric Disorders. Community Update. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA/RAND, 2000–04.

Wagner EH. The role of patient care teams in chronic disease management. BMJ. 2000;320(7234):569.

Wang PS, Simon GE, Kessler RC. Making the business case for enhanced depression care: the National Institute of Mental Health-Harvard Work Outcomes Research and Cost-effectiveness Study. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50(4):468–75.

Wells KB, Klap R, Koike A, Sherbourne C. Ethnic disparities in unmet need for alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health care. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(12):2027–32.

Wells KB, Sherbourne CD, Miranda J, Tang L, Benjamin B, Duan N. The cumulative effects of quality improvement for depression on outcome disparities over 9 years: results from a randomized, controlled group-level trial. Med Care. 2007;45(11):1052–9.

Zambrana RE. The role of Latino/Hispanic communities in health services research: strategies for a meaningful partnership. J Med Syst. 1996;20(5):317–28.

Khodyakov D, Shariff M, Dixon E, Mendel P, Chung B, Linski B, et al. An implementation evaluation of the community engagement and planning intervention in the CPIC depression care improvement trial. Community Ment Health J. In press.

Los Angeles County Department of Health Services. LA County Department of Health Services Key Health Indicators. Los Angeles, CA, 2009.

Murray DM. Design and analysis of group-randomized trials. USA: Oxford University Press; 1998.

Belin TR, Stockdale S, Tang L, Jones F, Jones A, Wright A, et al., eds. Developing a randomization protocol in a community-partnered participatory research project to reduce the burden of depression. Proceedings of the American Statistical Association Health Policy Statistics Section, Alexandria Virginia. 2010;5165–5171.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988.

Kish L. Survey sampling. New York: Wiley; 1965.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Ann. 2002;32(9):509–15.

Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;473–83.

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33.

Wong MD, Sarkisian CA, Davis C, Kinsler J, Cunningham WE. The association between life chaos, health care use, and health status among HIV-infected persons. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(9):1286–91.

Apicello J. A paradigm shift in housing and homeless services: applying the population and high-risk framework to preventing homelessness. Open Health Serv Policy J. 2010;3:41–52.

Gundersen C, Weinreb L, Wehler C, Hosmer D. Homelessness and food insecurity. J Hous Econ. 2003;12(3):250–72.

Sherbourne CD, Edelen MO, Zhou A, Bird C, Duan N, Wells KB. How a therapy-based quality improvement intervention for depression affected life events and psychological well-being over time: a 9-year longitudinal analysis. Med Care. 2008;46(1):78.

Little RJA. Missing-data adjustments in large surveys. J Bus Econ Stat. 1988;287–96.

Rubin D. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 1987.

Lavori PW, Dawson R, Shera D. A multiple imputation strategy for clinical trials with truncation of patient data. Stat Med. 1995;14(17):1913–25.

Tang L, Song J, Belin TR, Unützer J. A comparison of imputation methods in a longitudinal randomized clinical trial. Stat Med. 2005;24(14):2111–28.

Binder DA. On the variances of asymptotically normal estimators from complex surveys. Int Stat Rev. 1983;279–92.

Graubard BI, Korn EL. Predictive margins with survey data. Biometrics. 2004;55(2):652–9.

Kleinman LC, Norton EC. What’s the risk? A simple approach for estimating adjusted risk measures from nonlinear models including logistic regression. Health Serv Res. 2009;44(1):288–302.

Dunn OJ. Multiple comparisons among means. J Am Stat Assoc. 1961;56(293):52–64.

Miranda J, Green BL, Krupnick JL, Chung J, Siddique J, Belin T, et al. One-year outcomes of a randomized clinical trial treating depression in low-income minority women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(1):99.

Acknowledgements

We thank the 25 participating agencies of the Council and their representatives: QueensCare Health and Faith Partnership; COPE Health Solutions; UCLA Center for Health Services and Society; Cal State University Dominquez Hills; RAND; Healthy African American Families II; Los Angeles Urban League; Los Angeles Christian Health Centers; Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health and West Central Mental Health Center; Homeless Outreach Program/Integrated Care System; National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) Urban Los Angeles; Behavioral Health Services, Inc.; Avalon Carver Community Center; USC Keck School of Medicine Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences; Kaiser Watts Counseling and Learning Center; People Assisting the Homeless; Children’s Bureau; Saban Free Clinic; New Vision Church of Jesus Christ; Jewish Family Services of Los Angeles; St. John’s Well Child and Family Center; Charles Drew University of Medicine and Science; City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks; To Help Everyone Clinic; QueensCare Family Clinics and the National Institute of Mental Health (funder). We thank the participating Los Angeles programs, their providers and staff, and the clients who participated. We thank the RAND Survey Research Group and trained community members who conducted client data collection. We thank Robert Brook and Jurgen Unutzer for helpful comments on earlier drafts.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support

Community Partners in Care was funded by Award Numbers R01MH078853, P30MH082760, and P30MH068639 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The content is the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the funders.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic eupplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 55 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Wells, K.B., Jones, L., Chung, B. et al. Community-Partnered Cluster-Randomized Comparative Effectiveness Trial of Community Engagement and Planning or Resources for Services to Address Depression Disparities. J GEN INTERN MED 28, 1268–1278 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2484-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2484-3