Abstract

With the growth of new energy economy, proton exchange membrane fuel cell (PEMFC) has great potential to be success. However, the lack of high-performance catalyst layer (CL) especially at cathode limits its applications. It is becoming increasingly important to understand interface property during electrocatalytic oxygen reduction reaction (ORR). Here, the rotating disk electrode (RDE) method is developed to study the temperature and Nafion ionomer content effects on interface formed between Nafion and Pt/C. The results show that the temperature has the significant influence on electrochemical active sites, charging double capacitance, and reaction polarization resistance at low Nafion content region. Excess Nafion loaded in CLs will turn to self-reunion and increase the exposed active sites. We find that the optimum Nafion loading is in the range of 30 to 40 wt.%. The highest specific activity we achieve is 107.8 μA/cm2.Pt at 60 °C with 0.4 of ionomer/catalyst weight ratio, corresponding to the kinetic current 283.5 μA at 0.9 V. This finding provides new insights into enhancing the Pt utilization and designing high-efficiency catalysts for ORR.

The schematic diagram of the predicated interface and structure models of different Nafion content CLs under various temperatures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The first truly commercial fuel cell vehicle “Mirai” was released by Toyota in 2014 which means polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell (PEMFC) vehicles have successfully entered the market introduction period [1]. However, for large-scale commercial applications, PEMFCs still need to solve the large amount platinum cost at cathode because of sluggish oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) [2]. It is significantly important to optimize the configuration of the catalyst layer (CL) and achieve the efficient delivery of reactants and products in reaction interface [3, 4]. Over the last decade, extensive efforts have been paid to reducing the catalyst cost by using low Pt loading in the cathode, resulting in the decease of active sites and the increase of oxygen transfer resistance for ORR [5,6,7,8]. Meanwhile, the Nafion ionomer is widely used in the CL to stabilize the Pt-based catalyst and to improve the reaction interface for proton conductivity. However, this ionomer exists the sulfonate group which has been proposed to block Pt active sites [9, 10]. As a Teflon-based polymer, Nafion is demonstrated as an electron and anion insulator. Therefore, it is necessary to understand the ionomer roles during ORR and to optimize the Nafion content in CL for enhancing Pt utilization.

Nafion is used as a proton conductor and a binder in the CL created the three-phase interface (TPI) for the electrocatalytic reaction. Various studies show that the Nafion content and contribution have a strong impact on the microstructure and performance of the resulting CL. It is found that the optimized loading of Nafion, depending on the Pt loading and MEA fabricating process, ranges from 20 to 50 wt.% in membrane electrode assembly (MEA) [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. However, few researches are reported to study the formation mechanism of CL microstructure. It is thus difficult to understand the interfacial interaction between the catalyst and Nafion ionomer. According to Ma et al., Nafion is more likely to adsorb onto the surface of carbon support than the Pt surface. At low Nafion concentration, the adsorption behavior by hydrophilic bonding follows a Langmuir isotherm. The adsorption equilibrium constant depends on the properties of the catalyst surface [21]. Unfortunately, it is not possible to gain the comprehensive insights into the Nafion roles when conducting ORR operation due to the lack of electrochemical observations. Andersen et al. found that the catalyst surface exposure (CSE) will be decreased with increasing the amount of the Nafion up to 30 wt.%, and further increasing Nafion content will turn out to increase CSE due to Nafion aggregation. They emphasized that the proper content of Nafion covered catalyst surface is crucial to form an optimal electrode structure [22]. Actually, the coverage and morphology of Nafion are sensitive to the surface energy of the applied catalysts. It is widely accepted that systematic study of the ionomer phase in the electrode structure can be highly valuable to maximize the Pt utilization [23,24,25,26]. It is also worth noting that in the realistic MEA, ultrathin Nafion films used have completely different physical properties from the bulk material, including hydrophobicity, proton conductivity, water swelling properties, etc. [27,28,29]. Meanwhile, considering the variety of operational temperature in PEMFC, it is necessary to screen the temperature effect of on the formed Nafion phase.

Rotating disk electrode (RDE) as an electrochemical tool have shown its strong power to evaluate the catalyst performance with minimum testing time and cost assumption. Typically, it uses only a minimum amount of catalyst loaded into a small-area disk electrode in a three-electrode system [30]. Compared with the measurements conducted in a fuel cell, the RDE method has the advantage of low mass transport influence, feasibility of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), and reliable results of the material intrinsic performance [19]. Moreover, the temperature distribution on the CL will be uniform, and it is easy to control the testing temperature by heating the bulk electrolyte solution.

In this study, the CLs loaded with a wide range of ionomer content were prepared on the RDE electrode. The electrochemical performance were systematically characterized in a variety of temperature. The calculated Nafion thickness in the CLs were evaluated by closely packed structural theory.

Experiments

Catalysts, chemicals, and reactant gases

20 wt.% Platinum on Vulcan XC 72 (Carbon) was purchased from Johnson Matthey. Deionized (DI) water (> 18.2 MΩ·cm) was used for acid dilutions and glassware cleaning. The following chemicals were used in electrolyte preparation and ink formulation: isopropanol (IPA, CHROMASOLV® Plus, for HPLC, 99.9%, Sigma-Aldrich), Nafion solution (DE520, EW1000, 5%, 0.924 g·mL−1, Sigma-Aldrich), 50 nm alumina powder (Buehler Inc.), 70% perchloric acid Veritas® Doubly Distilled (GFS chemicals). All electrochemical measurements were carried out in 0.1 M HClO4. Gases used in this study were all classified as ultrapure grade (N2, 99.9999%, O2, 99.9999%, Wuhan Xiangyun Gas).

Instruments

A microbalance (OHAUS) and bath sonicator (FS30H, Fisher Scientific, output 42 kHz, 100 W) were employed in the preparation of catalyst inks. CHI660E operated with electrochemical analyzer/workstation was used to obtain cyclic voltammograms (CVs), ORR, and EIS curves, and the IR correction was applied in each scanning. RDE rotators, PTFE rotator shafts, and GC tips (5 mm in diameter, 0.196 cm2, embedded in a PTFE cylinder) were obtained from Pine Instruments. An optical microscope (AM4815ZT DinoLite Edge, Dino-Lite Digital Microscope) was routinely used to facilitate inspection of catalyst layers on GC. A JEOL JSM-7000F Field Emission Microscope was employed to obtain SEM images.

As shown in Fig. 1, the five ports electrochemical cell setup has the Pt counter electrode (CE), the saturated calomel electrode (SCE) as reference electrode (RE), and the RDE working electrode (WE) with the CLs. The SCE was calibrated by the reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE). The detailed cleaning procedure is described in our previous work [31].

Catalyst ink and CL fabrication

Inks were prepared by mixing 5 mg 20 wt.% Pt/C catalysts with 100 μL DI water, 900 μL IPA, and various volumes 5 wt.% Nafion solution. In this work, the studied ionomer/carbon (I/C) weight ratios included 0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, 1.6, 2.4, and 3.2. To form uniform dispersion, the catalyst ink was sonicated for 20 mins in an ice bath system. Six microliters of the inks was subsequently pipetted onto the GC disk (~ 30.6 μg Pt/cm2) followed by oven-drying in air at room temperature. The testing temperature was heated by a water bath. The morphology of catalyst layer was inspected to make sure a good dispersion during drying process.

Electrochemical testing

Considering the variable temperatures and the leak of Cl− ions in Ag/AgCl reference electrode, the SCE was chosen as the reference electrode used in our experiments. Prior to characterization, the SCE was calibrated by the RHE at 26 °C as shown in Fig. 2. For catalyst layer conditioning, potential cycling was conducted in the range − 0.3 to 0.9 V (vs SCE) at 500 mV·s−1 for 50–100 cycles. The charge of hydrogen underpotential deposition (HUPD) was obtained from the third cycle of CV measured in − 0.3 to 0.9 V (vs SCE) at 50 mV·s−1 under N2 atmosphere. The electrochemical active surface area (ECSA) was estimated using 210 mC·cm−2 Pt [10] and the double-layer capacitance (Cdl) was determined from 0.15 to 0.25 V (vs SCE). ORR curves were measured from − 0.3 to 0.9 V (vs SCE) at 10 mV·s−1 and 1600 rpm under 100 kPa O2 atmosphere. Correction for background currents was applied to all ORR curves measured with in situ correction of solution resistance. The apparent activity current Io and limiting current IL were reported at 0.9 and 0.4 V in the plots (Fig. S5-S8). In this study, all plot data of the SCE potentials were converted to RHE potentials based on Eqs. 1 and 2 [32].

The SCE was calibrated by RHE at 26 °C in H2-saturated 0.1 M HClO4 in a three-electrode systems, including Pt network working electrode, Pt wire counter electrode, and SCE as the reference electrode [32]

Where VRHE represents the potential of reversible hydrogen electrode, VSCE vs NHE represents the standard potential of Hg/Hg2Cl2 which was strongly depended on the temperature T (°C) [32].

It is well known that the mass-normalized capacitance (Cdl) was obtained by the following Eq. 3 and the ECSA was obtained by Eq. 4, where the ORR kinetic currents Ik was corrected by Eq. 5.

Where V1 and V2 are the cutoff potentials in CV, i is the instantaneous charge current, υ is the scan rate, Q(C) is the integral area between current and voltage related to hydrogen ion desorption from Pt surface. MPt is the catalyst loading in mass as constant quantity approach to 30.6 μg Pt/cm2.

For EIS testing, the frequency range 1–105 Hz and the voltage slightly lower than the open circuit potential for ORR were applied with 100 kPa O2 atmosphere for eliminating the mass transport effect as much as possible and studying the charge transfer resistance Rct in the CL. The perturbation voltage as 5 mV was set up for EIS testing. The proper equivalent circuit diagram as described in next discussion section was selected for obtaining the fitting data.

Results and discussion

Morphology of CLs

In CLs, the Nafion as the binder covered on the Pt/C needs to be well dispersed for the uniformity which has significant impact on ORR performance [30, 33]. Figure 3a shows that an optical microscope image of the CL on the GC with 0.8 of I/C ratio which is popular applied in MEAs [34]. The image shows that the GC was almost completely covered by the CL, although slightly coarse surface can be observed. Other proportions might have the similar images due to the same prepared process. Because of the particle size of carbon (around 40 nm) is nearly 10 times than Pt (2 nm to 5 nm), carbon can regard as the framework structure in the CL which determines the thickness [35]. Thus, based on the carbon loading, we can estimate that the thickness of the CL formed on the RDE is about 3.6 μm under the assumption of the whole covered on GC and evenly dispersed [36]. This estimation is empirical and has taken into account the practical porosity of the CL. As shown in Fig. 3b, the thickness observed by SEM on the fault is approximately the same with the predicted thickness. Therefore, it is believed that the prepared CLs have uniform dispersity and the deviation of preparation can be excluded.

ESCA and Cdl by cyclic voltammetry

The temperature effect on the ECSA was investigated in various Nafion content CLs. Figure 4a shows that as increasing the Nafion content, the ECSA of the CLs slowly increased and then decreased sharply. By varying temperature, there is an irregular change that could be found and ECAS seemed to be suppressed by increasing temperature (Fig. S1-S4). It is explained that the increase of ECSA with increasing Nafion loading under the low loading results from the improved TPI network [11, 35]. Based on EIS results, Singh et al. found the same trend in low Nafion content region (I/C < 0.6) [19]. In principal, the ECSA is determined by HUPD where only enough number of hydrogen ions can support the H+ deposition process nearby Pt surface covered by Nafion. Otherwise, the Pt sites will not be detected without Nafion ionomer. In high-speed rotating RDE will form a local turbulence, resulting in no direct contact with electrolyte solution. When no Nafion is available to provide the proton resources, the catalyst near GC has no hydrogen ions to finish the adsorption and desorption process [37]. In contrast, sulfonate in wetting Nafion can provide hydrogen ions to build the proton channel. With higher Nafion content, the ECSA decreased sharply due to the electron channel in CLs were destroyed [37]. However, Kazuma’s work indicated that the ESCA was insensitive with the Nafion content even if the value of I/C increases to 1.4 [30]. This difference may due to the discrepancy of Pt/C catalysts and very low loading used in their work, leading to few effects on the diffusion of H+ in the reaction interface. Meanwhile, we observed that the temperature increase resulted in the reduction of ECSA. It is suspected that the adsorption of sulfonate groups on the Pt surface can induce the H2O2 product at the Nafion-Pt/C interface when performing the CV scanning. Moreover, the H2O2 product rate increases with applied temperature [38]. Obviously, the H2O2 may oxidize Pt atoms, which significantly suppresses the electron transport and available active site.

The temperature effect on the double layer capacitance was also analyzed by the CV curves as shown in Fig. 4b. With the similar trend to ECSA, Cdl has a slow increase and then a sharp decrease as increasing ionomer content. It looks to be a more regular change in the studied temperature range. Singh et al. [19] pointed out that the presence of Nafion could reduce the double layer capacitance and raised up the mass transport resistance. Our results are obviously different, because it is observed that the Cdl increased with Nafion introducing to the CLs in the low loading range. The reason can be ascribed to the much larger current density under ORR in Singh’s work where the mass transport in the reaction interface is a more limited factor. Meanwhile, our work presented that the more OH bonds of water molecules point toward the Pt surface with increasing temperature to form Pt-H covalent bond, leading to the increase of the charging capacitance. Such observation has been rationalized by the simulating result of the water/Pt (111) interface [39].

ORR performance by linear scanning voltammetry

The details on the roles of temperature Nafion content CLs have shown in Fig. 5. Both temperature and Nafion loading had a significant effect on the ORR performance, which can be reflected by kinetic activity current Ik and limiting current ILim in Fig. S5-S8.

The temperature effect on ORR performance in various Nafion content CLs (ORR kinetic activity Ik at 0.9 V vs RHE and limiting current ILim at 0.4 V vs RHE, the simplified sketch on the electrode structure reprinted from reference [22]. Copyright 2016 Elsevier)

Both in the low Nafion content region, the ORR activity of the CLs is the lowest at 40 °C, and the highest at 60 °C. It is easy to understand that the Ik increased with temperature by Butler-Volmer equation [40]. Unexpectedly, the ORR activity of the CLs were obviously suppressed by the temperature of 40 °C when adding Nafion. This anomalous results are presumably due to the Nafion-Pt/C interface property change with temperature according to Paul’s work [29]. It was presented that the mobility of Nafion film is dependent on thermal annealing and its thickness. The blocking of Pt surface by the hydrophobic component of Nafion will lead to significant inhibition of ORR when the temperature increase from 20 to 40 °C. Our observation confirmed that it is easier to form hydrophobic structure caused by Nafion reconstruction on the reaction interface at 40 °C. However, when the reaction temperature further increase to 60 °C, the appearance of PtO or PtOH on the surface of Pt leads to a turnover of Nafion structure. As a result, more hydrophilic sulfonic groups directly contact with Pt which will be benefit for more TPIs established [41,42,43,44,45]. Meanwhile, it is clear to observe that the high and over region showed a similar ORR trend as low region.

To further investigate the temperature effect on oxygen mass transport properties in CLs, the limiting current ILim was expressed in Fig. 5. Unlike Ik, the limiting current decreased significantly when the Nafion introduced into CLs, indicating the oxygen transport was blocked by Nafion [10, 19, 30]. With the same Nafion content, the ILim in CLs also reduced with increasing temperature. It can be understood that the ability of adsorb ions on the Pt surface becomes stronger, resulting in an extra resistance for oxygen transport to the Pt surface. In addition, an important factor cannot be ignored that the solubility of oxygen in aqueous solution will decrease with temperature increase [46]. Thus, low oxygen concentration will lead to slow oxygen transport in CLs and accordingly, decrease the limiting current.

To further analyze the electrochemical features, the Nafion loading in CLs could be classified by three stages as low region, high region, and over region. The boundary line can be found in Fig. 5. The results show that the highest specific activity was 107.8 μA/cm2.Pt at 60 °C corresponding to the kinetic current of electrode 283.5mA@0.9V vs RHE when the I/C weight ratio was 0.4. If the density of Nafion resin was assumed as approximately 2.0 g/cm−3, the optimal Nafion loading to maximize the Pt utilization could be determined in the range of 30–40 wt.%. This result was consistent well with the vast majority reports in the literatures [12, 15, 17, 21, 34, 35, 47].

As illustrated at the left corner in Fig. 5, an over simplified sketch on the electrode structure depending on ionomer content was presented schematically through the axis scale. It indicates that a proper Nafion content will contribute to good surface coverage on Pt and high ORR performance. And the CSE is observed as a strong function of the operation temperature.

Charge transfer resistance and mass transfer resistance by EIS

The EIS patterns are shown to study the charge and mass transfer resistance in Fig. 6. It was operated under constant voltage mode slightly lower than the open circuit voltage (V = 0.66 V vs SCE) to minimize the impact of mass transfer in saturated oxygen atmosphere, [19]. The results were fitted by ZView® software provided by Scribner Associates Inc. A typical equivalent circuit for ORR at Pt/Nafion interface was established to simulate the experimental data as show in Fig. 6a. RS, Rct and Ws represent the ohmic resistance, charge transfer resistance, and finite-length Warburg impedance for oxygen transmission capacity, respectively. The conventional double-layer capacitance is replaced by a constant phase element (CPE) to account for non-uniform diffusion in pore structure CLs [48, 49].

Combining Table 1 with Fig. 6d, a slight decrease of Rs was found, indicating the ionic activity increased with the temperature. Meanwhile, the CPE exponent Φ (Fig. S9) can be suggested as a capacitor [50]. In Fig. 6e, the Rct decreases with the increase of temperature, when the range of I/C is from 0 to 1.6, and there is a minimum of Rct (10 Ω) at I/C = 0 and 60 °C. The results indicate that the higher temperature can improve ORR kinetic. In the range of I/C = 1.6 to 3.2, the Rct increases with Nafion content, and the highest value is achieved at 40 °C. This could be explained that the over-region Nafion content has the larger impact on kinetic process at this temperature. Compared with the low region and high region, the kinetic process at the over region become slower, possibly because the CL was wrapped by Nafion and the mass transfer process become dominated. Moreover, the hydrophobic surface could form easily at 40 °C because there exists confinement effect of oxygen inside layers of Nafion at low Pt loading CL [51]. As shown in Fig. 6f, the Ws results demonstrate that the oxygen transport capability can meet requirements for the kinetic-controlled process when Nafion content is in the range of I/C = 0 to 1.6. While in the over region of I/C = 1.6 to 3.2, the oxygen transmission capacity is drastically reduced. Furthermore, the higher temperature results in the decrease of Ws. This may be due to the presence of excessive Nafion, resulting in ionomer agglomeration which wrapped the catalyst surface. In this case, the numbers of electron transport channel, TPI and available Pt active sites will be decreased significantly. In addition, the higher temperature will lead to the stronger interaction between the Pt/C catalyst and Nafion ionomer, and the oxygen transport into the reaction interface will become more difficult [52].

Structural model of reaction interface for ORR

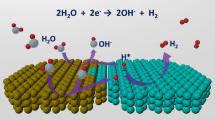

The above statement shows that the temperature has an important effect on the resulting reaction interface, as combined results of the catalyst utilization and mass transport. To further illustrate the impact of temperature and Nafion contents, the interface and its structural model are schematically represented in Fig. 7.

The structural model is constructed using a crystal-like face-centered cubic stacking structure according to a closely packed structural theory [53]. The basic material parameters can be found, including specific surface area Scarbon of Vulcan XC-72 (about 220 m2 g−1), and the diameter of the Pt particles (about 3 nm), the Pt specific surface area SPt (93 m2 g−1), and the dry Nafion density (2.0 g cm−3) [34]. Then, the theoretical thickness δNafion of Nafion adsorbed on the surface of the catalyst can be calculated by various I/C weigh ratios (Table S1). We found that the theoretical thickness of Nafion does not exceed 10 nm even at over region, which is not consistent with the thickness of the observed Nafion on the real catalyst surface [23]. This indicates that Nafion extremely prone to agglomerate in CLs structures. Thus, surface energy changes with temperature has a great possibility to change the nature of Nafion-Pt/C interface.

As shown in Fig. 7, Nafion consists of hydrophobic polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) backbone and hydrophilic side chain with SO3− group [26]. With increasing Nafion content, the amount of Nafion filled in the stack gap become more. Ultimately, the continuity of the carbon sphere skeleton can be destroyed, result in the loss of TPI and poor performance. In low region, the Nafion serves as the bonding agent and slightly covers on Pt/C surface. For Nafion-free CL, there is only electrolyte solution surrounded on RDE and the temperature effect is limited. But with adding Nafion, the temperature become the dominant effect for ORR performance especially at 40 °C, due to Nafion migration into CL surface. It is speculated that the much more hydrophobic PTFE backbones turn to face the Pt surface when Pt/C fully covered by nano-thin Nafion film. In the high region, this phenomenon is not obvious due to the thickness and aggregation increase of Nafion and the catalyst exposure is more than that in low region. The Nafion ionomer tends to from an agglomerated particle in contact with Pt/C [22]. In general, the Nafion covered the catalyst surface will hinder the oxygen transfer to reaction interface, which has become the major bottleneck for low Pt loading and high current density of PEMFCs [4, 7, 8]. As our knowledge, it is the first time to investigate the temperature effect on interface property with various Nafion contents in RDE system.

Conclusions

The temperature and Nafion content showed a strong effect on interface property and electrochemical performance for ORR. At low Nafion content region, the catalyst exposure may decrease due to the cover of nano-thin Nafion film and temperature has the significant influence on electrochemical active sites, charging double capacitance, and reaction polarization resistance. Both ECSA and Cdl show a slow increase with Nafion content in RDE system. Unlike complicated ECSA, Cdl has the regular and reasonable change in the studied temperature range. The addition of Nafion will inhibit the activity of the catalyst especially at 40 °C which may due to the easier formation of hydrophobic structure caused by Nafion reconstruction on the reaction interface. Excess Nafion will tend to self-reunion and increase the exposed active sites. The optimum Nafion loading can be found in our work is in the range of 30 to 40 wt.%. Additionally, the highest specific activity we can achieve is 107.8 μA/cm2.Pt at 60 °C with 0.4 of ionomer/catalyst weight ratio, corresponding to the kinetic current 283.5 μA at 0.9 V. This finding provides new insights into enhancing the Pt utilization and designing high-efficiency catalysts for ORR.

References

Yoshida T, Kojima K (2015) Toyota MIRAI fuel cell vehicle and progress toward a future hydrogen society. Electrochem Soc Interface 24(2):45–49

Gröger O, Gasteiger HA, Suchsland J-P (2015) Review—electromobility: batteries or fuel cells? J Electrochem Soc 162(14):A2605–A2622

Kongkanand A, Mathias MF (2016) The priority and challenge of high-power performance of low-platinum proton-exchange membrane fuel cells. J Phys Chem Lett 7(7):1127–1137

Weber AZ, Kusoglu A (2014) Unexplained transport resistances for low-loaded fuel-cell catalyst layers. J Mater Chem A 2(41):17207–17211

Kinoshita S, Tanuma T, Yamada K, Hommura S, Watakabe A, Saito S, Shimohira T (2014) (Invited) development of PFSA ionomers for the membrane and the electrodes. ECS Trans 64(3):371–375

Mashio T, Iden H, Ohma A, Tokumasu T (2017) Modeling of local gas transport in catalyst layers of PEM fuel cells. J Electroanal Chem 790:27–39

Ono Y, Ohma A, Shinohara K, Fushinobu K (2013) Influence of equivalent weight of ionomer on local oxygen transport resistance in cathode catalyst layers. J Electrochem Soc 160(8):F779–F787

Putz AMV, Susac D, Berejnov V, Wu J, Hitchcock AP, Stumper J (2016) (Plenary) doing more with less: challenges for catalyst layer design. ECS Trans 75(14):3–23

Shinozaki K, Morimoto Y, Pivovar BS, Kocha SS (2016) Suppression of oxygen reduction reaction activity on Pt-based electrocatalysts from ionomer incorporation. J Power Sources 325:745–751

Zhu S, Hu X, Zhang L, Shao M (2016) Impacts of perchloric acid, Nafion, and alkali metal ions on oxygen reduction reaction kinetics in acidic and alkaline solutions. J Phys Chem C 120(48):27452–27461

Passalacqua E, Lufrano F, Squadrito G, Patti A, Giorgi L (2001) Nafion content in the catalyst layer of polymer electrolyte fuel cells: effects on structure and performance. Electrochim Acta 46(6):799–805

Sasikumar G, Ihm JW, Ryu H (2004) Dependence of optimum Nafion content in catalyst layer on platinum loading. J Power Sources 132(1–2):11–17

Yano H, Higuchi E, Uchida H, Watanabe M (2006) Temperature dependence of oxygen reduction activity at Nafion-coated bulk Pt and Pt/carbon black catalysts. J Phys Chem B 110(33):16544–16549

Lee SK, Pyun SI, Lee SJ, Jung KN (2007) Mechanism transition of mixed diffusion and charge transfer-controlled to diffusion-controlled oxygen reduction at Pt-dispersed carbon electrode by Pt loading, Nafion content and temperature. Electrochim Acta 53(2):740–751

Lee D, Hwang S (2008) Effect of loading and distributions of Nafion ionomer in the catalyst layer for PEMFCs. Int J Hydrog Energy 33(11):2790–2794

Ma S, Solterbeck CH, Odgaard M, Skou E (2009) Microscopy studies on pronton exchange membrane fuel cell electrodes with different ionomer contents. Appl Phys A 96(3):581–589

Xie JA et al (2010) Influence of ionomer content on the structure and performance of PEFC membrane electrode assemblies. Electrochim Acta 55(24):7404–7412

Suzuki A, Sen U, Hattori T, Miura R, Nagumo R, Tsuboi H, Hatakeyama N, Endou A, Takaba H, Williams MC, Miyamoto A (2011) Ionomer content in the catalyst layer of polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell (PEMFC): effects on diffusion and performance. Int J Hydrog Energy 36(3):2221–2229

Singh RK, Devivaraprasad R, Kar T, Chakraborty A, Neergat M (2015) Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy of oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) in a rotating disk electrode configuration: effect of ionomer content and carbon-support. J Electrochem Soc 162(6):F489–F498

Takahashi S, Mashio T, Horibe N, Akizuki K, Ohma A (2015) Analysis of the microstructure formation process and its influence on the performance of polymer electrolyte fuel-cell catalyst layers. ChemElectroChem 2(10):1560–1567

Ma S et al (2007) 19F NMR studies of Nafion™ ionomer adsorption on PEMFC catalysts and supporting carbons. Solid State Ionics 178(29–30):1568–1575

Andersen SM, Grahl-Madsen L (2016) Interface contribution to the electrode performance of proton exchange membrane fuel cells—impact of the ionomer. Int J Hydrog Energy 41(3):1892–1901

Lopez-Haro M, Guétaz L, Printemps T, Morin A, Escribano S, Jouneau PH, Bayle-Guillemaud P, Chandezon F, Gebel G (2014) Three-dimensional analysis of Nafion layers in fuel cell electrodes. Nat Commun 5:5229

Holdcroft S (2014) Fuel cell catalyst layers: a polymer science perspective. Chem Mater 26(1):381–393

Cho MK, Park HY, Lee SY, Lee BS, Kim HJ, Henkensmeier D, Yoo SJ, Kim JY, Han J, Park HS, Sung YE, Jang JH (2017) Effect of catalyst layer ionomer content on performance of intermediate temperature proton exchange membrane fuel cells (IT-PEMFCs) under reduced humidity conditions. Electrochim Acta 224:228–234

Kusoglu A, Weber AZ (2017) New insights into perfluorinated sulfonic-acid ionomers. Chem Rev 117(3):987–1104

Kurihara Y, Mabuchi T, Tokumasu T (2017) Molecular analysis of structural effect of ionomer on oxygen permeation properties in PEFC. J Electrochem Soc 164(6):F628–F637

Paul DK, Karan K (2014) Conductivity and wettability changes of ultrathin Nafion films subjected to thermal annealing and liquid water exposure. J Phys Chem C 118(4):1828–1835

Paul DK, Shim HKK, Giorgi JB, Karan K (2016) Thickness dependence of thermally induced changes in surface and bulk properties of Nafion® nanofilms. J Polym Sci B Polym Phys 54(13):1267–1277

Shinozaki K, Zack JW, Pylypenko S, Pivovar BS, Kocha SS (2015) Oxygen reduction reaction measurements on platinum electrocatalysts utilizing rotating disk electrode technique II. Influence of ink formulation, catalyst layer uniformity and thickness. J Electrochem Soc 162(12):F1384–F1396

Sun S, Pan M (2014) The activity influence of isopropyl alcohol for flat plant Pt and Pt/C electrode. ECS Trans 59(1):289–294

Spitzer P, Wunderli S, Maksymiuk K, et al (2013) Reference Electrodes for Aqueous Solutions [M]//Handbook of Reference Electrodes. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Heidelberg, p 77–143

Shinozaki K, Zack JW, Richards RM, Pivovar BS, Kocha SS (2015) Oxygen reduction reaction measurements on platinum electrocatalysts utilizing rotating disk electrode technique I. Impact of impurities, measurement protocols and applied corrections. J Electrochem Soc 162(10):F1144–F1158

Kocha SS (2010) Principles of MEA preparation. In: Vielstich W, Lamm A, Gasteiger HA, Yokokawa H (eds) Handbook of fuel cells. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470974001.f303047

Suzuki T, Tsushima S, Hirai S (2011) Effects of Nafion® ionomer and carbon particles on structure formation in a proton-exchange membrane fuel cell catalyst layer fabricated by the decal-transfer method. Int J Hydrog Energy 36(19):12361–12369

Liu Y et al (2008) Dependence of electrode proton resistivity on electrode thickness and ionomer equivalent weight in cathode catalyst layer in PEM fuel cell. ECS Trans 16(2):1775–1786

Seel D et al (2009) Handbook of fuel cells-fundamentals, technology and applications. Wiley, Amsterdam

Yano H, Uematsu T, Omura J, Watanabe M, Uchida H (2015) Effect of adsorption of sulfate anions on the activities for oxygen reduction reaction on Nafion®-coated Pt/carbon black catalysts at practical temperatures. J Electroanal Chem 747:91–96

He Y, Chen C, Yu H, Lu G (2017) Effect of temperature on compact layer of Pt electrode in PEMFCs by first-principles molecular dynamics calculations. Appl Surf Sci 392(Supplement C):109–116

Hamnett A (2010) Kinetics of electrochemical reactions. In: Vielstich W, Lamm A, Gasteiger HA, Yokokawa H (eds) Handbook of fuel cells. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470974001.f101005

Long Z, Gao L, Li Y, Kang B, Lee JY, Ge J, Liu C, Ma S, Jin Z, Ai H (2017) Micro galvanic cell to generate PtO and extend the triple-phase boundary during self-assembly of Pt/C and Nafion for catalyst layers of PEMFC. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 9(44):38165–38169

Liu Y, Mathias M, Zhang J (2010) Measurement of platinum oxide coverage in a proton exchange membrane fuel cell. Electrochem Solid-State Lett 13(1):B1–B3

Subramanian N et al (2012) Pt-oxide coverage-dependent oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) kinetics. J Electrochem Soc 159(5):B531–B540

Huang Y, Wagner FT, Zhang J, Jorné J (2014) On the nature of platinum oxides on carbon-supported catalysts. J Electroanal Chem 728:112–117

Jia Q, Caldwell K, Ziegelbauer JM, Kongkanand A, Wagner FT, Mukerjee S, Ramaker DE (2014) The role of OOH binding site and Pt surface structure on ORR activities. J Electrochem Soc 161(14):F1323–F1329

Tromans D (1998) Temperature and pressure dependent solubility of oxygen in water: a thermodynamic analysis. Hydrometallurgy 48(3):327–342

Alekseenko AA, Guterman VE, Volochaev VA (2016) Microstructure optimization of Pt/C catalysts for PEMFC. In: Parinov IA, Chang S-H, Topolov VY (eds) Advanced materials: manufacturing, physics, mechanics and applications. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 37–49

Yuan X et al (2007) AC impedance technique in PEM fuel cell diagnosis—a review. Int J Hydrog Energy 32(17):4365–4380

Xie Z, Holdcroft S (2004) Polarization-dependent mass transport parameters for orr in perfluorosulfonic acid ionomer membranes: an EIS study using microelectrodes. J Electroanal Chem 568(Supplement C):247–260

Chlistunoff J, Sansiñena J-M (2016) Nafion induced surface confinement of oxygen in carbon-supported oxygen reduction catalysts. J Phys Chem C 120(49):28038–28048

Bondarenko AS, Stephens IEL, Hansen HA, Pérez-Alonso FJ, Tripkovic V, Johansson TP, Rossmeisl J, Nørskov JK, Chorkendorff I (2011) The Pt(111)/electrolyte interface under oxygen reduction reaction conditions: an electrochemical impedance spectroscopy study. Langmuir 27(5):2058–2066

Mashio T, Ohma A, Tokumasu T (2016) Molecular dynamics study of ionomer adsorption at a carbon surface in catalyst ink. Electrochim Acta 202:14–23

Sun S, Zhang G, Gauquelin N, Chen N, Zhou J, Yang S, Chen W, Meng X, Geng D, Banis MN, Li R, Ye S, Knights S, Botton GA, Sham TK, Sun X (2013) Single-atom catalysis using Pt/graphene achieved through atomic layer deposition. Sci Rep 3:1775

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by The National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2016YFB0101205) and Hubei Province Technology Innovation Project (Program No. 2016AAA047).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOC 1520 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Y., Zhong, Q., Li, G. et al. Electrochemical study of temperature and Nafion effects on interface property for oxygen reduction reaction. Ionics 24, 3905–3914 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11581-018-2533-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11581-018-2533-3