Abstract

Purpose

Positive airway pressure (PAP) adherence is poor in comorbid OSA/PTSD. SensAwake™ (SA) is a wake-sensing PAP algorithm that lowers pressure when wake is detected. We compared auto-PAP (aPAP) with and without SA for comorbid OSA/PTSD.

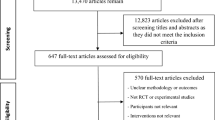

Methods

Prospective, randomized crossover study comparing aPAP to aPAP + SA. We enrolled patients with OSA/PTSD who were PAP naïve. Four weeks after randomization, the patients were crossed over to the alternate treatment group, with final follow-up at eight weeks. Sleep questionnaires (ESS, ISI, FSS, and FOSQ-10) were assessed at baseline and follow-up.

Results

We enrolled 85 patients with OSA/PTSD. aPAP reduced AHI to < 5/h in both groups. Our primary endpoint, average hours of aPAP adherence (total) after 4 weeks, was significantly increased in the SA group in our intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis (ß = 1.13 (95% CI 0.16–2.1); p = 0.02), after adjustment for ESS differences at baseline. After adjustment for ESS, SA (ITT analysis) also showed significant improvement in percentage of nights used for ≥ 4 h (ß = 14.9 (95% CI 1.02–28.9); p = 0.04). There were trends toward an increase in percentage nights used total (ß = 17.4 (95% CI − 0.1 to 34.9); p = 0.05), average hours of aPAP adherence (nights used) (ß = 1.04 (95% CI − 0.07 to 2.1); p = 0.07), and regular use (OR = 7.5 (95% CI 0.9–64.7); p = 0.07) after adjustment for ESS at baseline. After adjustment for ESS and days to cross over, SA by actual assignment did not show any effect on adherence variables. The ESS, ISI, FSS, and FOSQ-10 all showed significant improvements with PAP, but there were no differences in the magnitude of improvement in any score between groups.

Conclusions

Adherence to aPAP may be improved with the addition of SA and deserves further study. SA is as effective as standard aPAP for normalizing the AHI and improving sleep-related symptoms.

Clinical trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02549508

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02549508?term=NCT02549508&rank=1

“Comparison Study Using APAP With and Without SensAwake in Patients With OSA and PTSD”.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- AASM:

-

American Academy of Sleep Medicine

- AHI:

-

apnea–hypopnea index

- CPAP:

-

continuous positive airway pressure

- aPAP:

-

auto-PAP (auto-adjustable continuous positive airway pressure)

- ESS:

-

Epworth Sleepiness Scale

- FOSQ:

-

Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire

- FSS:

-

Fatigue Severity Scale

- ISI:

-

Insomnia Severity Index

- ITT:

-

intention-to-treat analysis

- OSA:

-

obstructive sleep apnea

- PAP:

-

positive airway pressure

- PCL:

-

PTSD checklist

- PSG:

-

polysomnography

- PTAF:

-

pressure transducer airflow

- PTSD:

-

post-traumatic stress disorder

- SA:

-

SensAwake™ (SA; Fisher and Paykel Healthcare, Auckland, New Zealand)

- WRNMMC:

-

Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, MD

References

El-Solh AA, Vermont L, Homish GG, Kufel T (2017) The effect of continuous positive airway pressure on post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder and obstructive sleep apnea: a prospective study. Sleep Med 33:145–150

Thomas JL, Wilk JE, Riviere LA, McGurk D, Castro CA, Hoge CW (2010) Prevalence of mental health problems and functional impairment among active component and National Guard soldiers 3 and 12 months following combat in Iraq. Arch Gen Psychiatry 67(6):614–623

Babson KA, Feldner MT (2010) Temporal relations between sleep problems and both traumatic event exposure and PTSD: a critical review of the empirical literature. J Anxiety Disord 24(1):1–15

Mustafa M, Erokwu N, Ebose I, Strohl K (2005) Sleep problems and the risk for sleep disorders in an outpatient veteran population. Sleep & Breathing = Schlaf & Atmung 9(2):57–63

Mysliwiec V, Gill J, Lee H, Baxter T, Pierce R, Barr TL, Krakow B, Roth BJ (2013) Sleep disorders in US military personnel: a high rate of comorbid insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea. Chest 144(2):549–557

Mysliwiec V, O'Reilly B, Polchinski J, Kwon HP, Germain A, Roth BJ (2014) Trauma associated sleep disorder: a proposed parasomnia encompassing disruptive nocturnal behaviors, nightmares, and REM without atonia in trauma survivors. J Clin Sleep Med 10(10):1143–1148

Seelig AD, Jacobson IG, Smith B, Hooper TI, Boyko EJ, Gackstetter GD, Gehrman P, Macera CA, Smith TC (2010) Sleep patterns before, during, and after deployment to Iraq and Afghanistan. Sleep 33(12):1615–1622

Krakow B, Haynes PL, Warner TD, Santana E, Melendrez D, Johnston L, Hollifield M, Sisley BN, Koss M, Shafer L (2004) Nightmares, insomnia, and sleep-disordered breathing in fire evacuees seeking treatment for posttraumatic sleep disturbance. J Trauma Stress 17(3):257–268

Krakow B, Melendrez D, Pedersen B, Johnston L, Hollifield M, Germain A, Koss M, Warner TD, Schrader R (2001) Complex insomnia: insomnia and sleep-disordered breathing in a consecutive series of crime victims with nightmares and PTSD. Biol Psychiatry 49(11):948–953

Krakow B, Melendrez D, Warner TD, Clark JO, Sisley BN, Dorin R, Harper RM, Leahigh LK, Lee SA, Sklar D, Hollifield M (2006) Signs and symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing in trauma survivors: a matched comparison with classic sleep apnea patients. J Nerv Ment Dis 194(6):433–439

Mysliwiec V, McGraw L, Pierce R, Smith P, Trapp B, Roth BJ (2013) Sleep disorders and associated medical comorbidities in active duty military personnel. Sleep 36(2):167

Sharafkhaneh A, Giray N, Richardson P, Young T, Hirshkowitz M (2005) Association of psychiatric disorders and sleep apnea in a large cohort. Sleep 28(11):1405–1411

Williams SG, Collen J, Orr N, Holley AB, Lettieri CJ (2015) Sleep disorders in combat-related PTSD. Sleep Breath 19(1):175–182

Youakim JM, Doghramji K, Schutte SL (1998) Posttraumatic stress disorder and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Psychosomatics 39(2):168–171

Lettieri CJ, Williams SG, Collen JF (2016) OSA syndrome and posttraumatic stress disorder: clinical outcomes and impact of positive airway pressure therapy. Chest 149(2):483–490

Mysliwiec V, Matsangas P, Gill J, Baxter T, O'Reilly B, Collen JF, Roth BJ (2015) A comparative analysis of sleep disordered breathing in active duty service members with and without combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Sleep Med 11(12):1393–1401

Hoge CW, Terhakopian A, Castro CA, Messer SC, Engel CC (2007) Association of posttraumatic stress disorder with somatic symptoms, health care visits, and absenteeism among Iraq war veterans. Am J Psychiatry 164(1):150–153

Krakow B, Lowry C, Germain A, Gaddy L, Hollifield M, Koss M, Tandberg D, Johnston L, Melendrez D (2000) A retrospective study on improvements in nightmares and post-traumatic stress disorder following treatment for co-morbid sleep-disordered breathing. J Psychosom Res 49(5):291–298

Mann JJ, Ellis SP, Waternaux CM, Liu X, Oquendo MA, Malone KM, Brodsky BS, Haas GL, Currier D (2008) Classification trees distinguish suicide attempters in major psychiatric disorders: a model of clinical decision making. J Clin Psychiatry 69(1):23–31

Nadorff MR, Nazem S, Fiske A (2013) Insomnia symptoms, nightmares, and suicide risk: duration of sleep disturbance matters. Suicide Life Threat Behav 43(2):139–149

Nadorff MR, Pearson MD, Golding S (2016) Explaining the relation between nightmares and suicide. J Clin Sleep Med 12(3):289–290

Bernert RA, Joiner TE (2007) Sleep disturbances and suicide risk: a review of the literature. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 3(6):735–743

Bernert RA, Joiner TE Jr, Cukrowicz KC, Schmidt NB, Krakow B (2005) Suicidality and sleep disturbances. Sleep 28(9):1135–1141

Bernert RA, Nadorff MR (2015) Sleep disturbances and suicide risk. Sleep Med Clin 10(1):35–39

Bryan CJ, Gonzales J, Rudd MD, Bryan AO, Clemans TA, Ray-Sannerud B, Wertenberger E, Leeson B, Heron EA, Morrow CE et al (2015) Depression mediates the relation of insomnia severity with suicide risk in three clinical samples of U.S. military personnel. Depress Anxiety 32(9):647–655

Hom MA, Lim IC, Stanley IH, Chiurliza B, Podlogar MC, Michaels MS, Buchman-Schmitt JM, Silva C, Ribeiro JD, Joiner TE Jr (2016) Insomnia brings soldiers into mental health treatment, predicts treatment engagement, and outperforms other suicide-related symptoms as a predictor of major depressive episodes. J Psychiatr Res 79:108–115

Collen JF, Lettieri CJ, Hoffman M (2012) The impact of posttraumatic stress disorder on CPAP adherence in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med 8(6):667–672

El-Solh AA, Ayyar L, Akinnusi M, Relia S, Akinnusi O (2010) Positive airway pressure adherence in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Sleep 33(11):1495–1500

Chilcoat HD, Breslau N (1998) Posttraumatic stress disorder and drug disorders: testing causal pathways. Arch Gen Psychiatry 55(10):913–917

Keuroghlian AS, Kamen CS, Neri E, Lee S, Liu R, Gore-Felton C (2011) Trauma, dissociation, and antiretroviral adherence among persons living with HIV/AIDS. J Psychiatr Res 45(7):942–948

Lockwood A, Steinke DT, Botts SR (2009) Medication adherence and its effect on relapse among patients discharged from a Veterans Affairs posttraumatic stress disorder treatment program. Ann Pharmacother 43(7):1227–1232

Safren SA, Gershuny BS, Hendriksen E (2003) Symptoms of posttraumatic stress and death anxiety in persons with HIV and medication adherence difficulties. AIDS Patient Care STDs 17(12):657–664

Shemesh E, Rudnick A, Kaluski E, Milovanov O, Salah A, Alon D, Dinur I, Blatt A, Metzkor M, Golik A, Verd Z, Cotter G (2001) A prospective study of posttraumatic stress symptoms and nonadherence in survivors of a myocardial infarction (MI). Gen Hosp Psychiatry 23(4):215–222

Spoont M, Sayer N, Nelson DB (2005) PTSD and treatment adherence: the role of health beliefs. J Nerv Ment Dis 193(8):515–522

El-Solh AA, Ayyar L, Akinnusi M, Relia S, Akinnusi O (2010) Positive airway pressure adherence in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Sleep 33(11):6

Loube DI, Gay PC, Strohl KP, Pack AI, White DP, Collop NA (1999) Indications for positive airway pressure treatment of adult obstructive sleep apnea patients: a consensus statement. Chest 115(3):863–866

Brown LK, Javaheri S (2017) Positive airway pressure device technology past and present: what's in the “black box”? Sleep Med Clin 12(4):501–515

Rapoport DM, Norman RG, inventors; New York University, New York, NY, assigned. Positive airway pressure system and method for treatment of sleeping disorder in patient. US patent 6,988,994. January 24, 2006

Ayappa I, Norman RG, Whiting D, Tsai AH, Anderson F, Donnely E, Silberstein DJ, Rapoport DM (2009) Irregular respiration as a marker of wakefulness during titration of CPAP. Sleep 32(1):99–104

Dungan GC 2nd, Marshall NS, Hoyos CM, Yee BJ, Grunstein RR (2011) A randomized crossover trial of the effect of a novel method of pressure control (SensAwake) in automatic continuous positive airway pressure therapy to treat sleep disordered breathing. J Clin Sleep Med 7(3):261–267

Kushida C, Littner MR, Morgenthaler T et al (2005) Practice parameters for the indications for polysomnography and related procedures: an update for 2005. Sleep 28:499–521

Berry R, Brooks R, Gamaldo CE, et al (2015) for the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events: rules, terminology and technical specifications, Version 2.2. In. www.aasmnet.org: AASM

The Report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force (1999) Sleep-related breathing disorders in adults: recommendations for syndrome definition and measurement techniques in clinical research. Sleep 22(5):667–689

Bogan RK, Wells C (2017) A randomized crossover trial of a pressure relief technology (SensAwake) in continuous positive airway pressure to treat obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Disord 2017:3978073

Weathers F, Litz B, Herman D, Huska J, Keane T (1993) The PTSD Checklist (PCL): reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. In: Paper presented at 9th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies 9th Annual Meeting. San Antonio, TX

Weathers F, Huska J, Keane T (1991) The PTSD checklist military version (PCL-M). National Center for PTSD, Boston

Johns M (1993) Daytime sleepiness, snoring, and obstructive sleep apnea. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Chest 103:30–36

Morin C, Belleville G, Bélanger L, Ivers H (2011) The insomnia severity index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep 34:601–608

Chasens E, Ratcliffe SJ, Weaver TE (2009) Development of the FOSQ-10: a short version of the functional outcomes of sleep questionnaire. Sleep 32:915–919

The PTSD Checklist (PCL): reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Frank W Weathers, Brett T Litz, Debra S Herman, Jennifer A Huska, and Terence M Keane. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, San Antonio, TX, October 1993

Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris C (1996) Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL). Behav Res Ther 34(8):669–673

PCL Scoring information for DSM-IV. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/documents/PCL_Scoring_Information.pdf (Accessed 26 April 2019)

PCL Psychometric information for DSM-IV. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/documents/PCL_Psychometric_Information.pdf (Accessed 26 April 2019)

Using the PTSD checklist for DSM-IV. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/documents/PCL_handoutDSM4.pdf (Accessed 26 April 2019).

Forbes D, Creamer M, Biddle D (2001) The validity of the PTSD checklist as a measure of symptomatic change in combat-related PTSD. Behav Res Ther 39(8):977–986

Krupp LB, LaRocca NG, Muir-Nash J, Steinberg AD (1989) The fatigue severity scale. Application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Neurol 46(10):1121–1123

Kribbs NB, Pack AI, Kline LR, Smith PL, Schwartz AR, Schubert NM, Redline S, Henry JN, Getsy JE, Dinges DF (1993) Objective measurement of patterns of nasal CPAP use by patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis 147(4):887–895

Johns MW (1991) A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep 14(6):540–545

Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM (2001) Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med 2(4):297–307

Weaver TE, Laizner AM, Evans LK, Maislin G, Chugh DK, Lyon K, Smith PL, Schwartz AR, Redline S, Pack AI et al (1997) An instrument to measure functional status outcomes for disorders of excessive sleepiness. Sleep 20(10):835–843

Weaver TE, Maislin G, Dinges DF, Bloxham T, George CF, Greenberg H, Kader G, Mahowald M, Younger J, Pack AI (2007) Relationship between hours of CPAP use and achieving normal levels of sleepiness and daily functioning. Sleep 30(6):711–719

El-Solh AA, Homish GG, Ditursi G, Lazarus J, Rao N, Adamo D, Kufel T (2017) A randomized crossover trial evaluating continuous positive airway pressure versus mandibular advancement device on health outcomes in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Sleep Med 13(11):1327–1335

Orr JE, Smales C, Alexander TH, Stepnowsky C, Pillar G, Malhotra A, Sarmiento KF (2017) Treatment of OSA with CPAP is associated with improvement in PTSD symptoms among veterans. J Clin Sleep Med 13(1):57–63

Tamanna S, Parker JD, Lyons J, Ullah M (2014) The effect of continuous positive air pressure (CPAP) on nightmares in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine: JCSM: Official Publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine 10(6):631

Edwards BA, Eckert DJ, McSharry DG, Sands SA, Desai A, Kehlmann G, Bakker JP, Genta PR, Owens RL, White DP et al (2014) Clinical predictors of the respiratory arousal threshold in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 190(11):1293–1300

Holley AB, Londeree WA, Sheikh KL, Andrada TF, Powell TA, Khramtsov A, Hostler JM (2018) Zolpidem and Eszopiclone pre-medication for PSG: effects on staging, titration, and adherence. Mil Med 183(7–8):e251–e256

Holley AB, Walter RJ (2018) Does a low arousal threshold equal low PAP adherence? J Clin Sleep Med 14(5):713–714

Hostler JM, Sheikh KL, Andrada TF, Khramtsov A, Holley PR, Holley AB (2017) A mobile, web-based system can improve positive airway pressure adherence. J Sleep Res 26(2):139–146

Smith PR, Sheikh KL, Costan-Toth C, Forsthoefel D, Bridges E, Andrada TF, Holley AB (2017) Eszopiclone and zolpidem do not affect the prevalence of the low arousal threshold phenotype. J Clin Sleep Med 13(1):115–119

Acknowledgments

All of the study authors contributed to the study and have reviewed the final manuscript. Dr. Holley conceived the research idea and performed statistical analysis and manuscript editing. Dr. Shaha contributed to data collection and analysis and assisted in the first draft of the manuscript. Mr. Terry contributed to patient recruitment, data collection, and data analysis. Dr. Costan-Toth contributed to data collection and data analysis. Dr. Slowik contributed to data collection and analysis. Dr. Robertson contributed to patient recruitment and data analysis. Dr. Williams contributed to patient recruitment and data collection. Ms. Golden contributed to patient recruitment, data collection, and analysis. Mr. Andrada contributed to data collection. Ms. Skeete contributed to patient recruitment and data collection. Ms. Sheikh contributed to patient recruitment and data collection. Mr. Butler contributed to data collection. Dr. Collen is the guarantor of the final article and is responsible for the integrity of the data and contents of this manuscript from study inception to publication of the final product.

Funding

This study was funded by Fisher-Paykel Healthcare (Grant #WR-GVA-FPH-10-32). This investigator-initiated project was conducted by using an unrestricted research grant and PAP machines provided by Fisher & Paykel Healthcare to the Geneva Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine. Fisher & Paykel Healthcare was involved with the study design, but not with patient enrollment, data collection and interpretation, manuscript preparation, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None of the study authors have any relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Statement and declarations

All authors have seen and approve the manuscript. This investigator-initiated project was conducted by using an unrestricted research grant and PAP machines provided by Fisher & Paykel Healthcare to the Geneva Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine. Fisher & Paykel Healthcare was involved with the study design, but not with patient enrollment, data collection and interpretation, manuscript preparation, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The study authors have no other relevant disclosures.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

E-Table 1: Baseline description of study population (demographic and clinical characteristics) based on treatment received. E-Table 2: PAP adherence for aPAP with SA-ON and SA-OFF based on treatment received. Residual (Treated) “AHI” (PAP estimated residual respiratory disturbance index), measures of PAP leak, and minimum and maximum PAP pressures. 1. Overall percentage of nights PAP was used during the study (“Nights used (%)”). 2. Percent of nights with use greater than or equal to 4 h (“Nights ≥ 4 h (%)”). 3. Average hours of use per night, over total nights (“Hours/nights, total”). 4. Average hours of use per night, averaged only over the nights PAP was actually used (worn) (“Hours/nights, used”). 5. Regular use = ≥ 4 h for ≥ 70% of nights [57] (DOCX 16 kb)

ESM 2

E-Table 3: by treatment received. PAP adherence by treatment received, with adjustment for differences at baseline. 1. Average hours of use per night, averaged only over the nights PAP was actually used (worn) (“Hours/nights, used”). 2. Average hours of use per night, over total nights (“Hours/nights, total”). 3. Overall percentage of nights PAP was used during the study (“Nights used (%)”). 4. Percent of nights with use greater than or equal to 4 h (“Nights ≥ 4 h (%)”). 5. Regular use = ≥ 4 h for ≥ 70% of nights [57]. E-Table 4: Differences in sleep-related symptoms at 4 weeks by intention-to-treat and by treatment received. E-Table 5: Intra-patient comparisons for PAP adherence by treatment received. 1. Overall percentage of nights PAP was used during the study (“Nights used (%)”). 2. Percent of nights with use greater than or equal to 4 h (“Nights ≥ 4 h (%)”). 3. Average hours of use per night, over total nights (“Hours/nights, total”). 4. Average hours of use per night, averaged only over the nights PAP was actually used (worn) (“Hours/nights, used”) (DOCX 16 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Holley, A., Shaha, D., Costan-Toth, C. et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial using a novel PAP delivery platform to treat patients with OSA and comorbid PTSD. Sleep Breath 24, 1001–1009 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-019-01936-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-019-01936-x