Abstract

Earthquakes are among the most horrible events of nature due to unexpected occurrence, for which no spiritual means are available for protection. The only way of preserving life and property is to prepare for the inevitable: applying earthquake-resistant construction methods. Zones of damaging earthquakes along the Silk Road are reviewed for seismic hazard and to understand the ways local civilizations coped with it during the past two thousand years. China and its wide sphere of cultural influence certainly had earthquake-resistant architectural practice, as the high number of ancient buildings, especially high pagodas, prove. A brief review of anti-seismic design and construction methods (applied both for wooden and masonry buildings) is given, in the context of earthquake-prone zones of Northern China. Muslim architects in Western China and Central Asia used brick and mortar to construct earthquake-resistant structural systems. Ancient Greek architects in Anatolia and the Aegean applied steel clamps embedded in lead casing to hold together columns and masonry walls during frequent earthquakes. Romans invented concrete and built all sizes of buildings as a single, non-flexible unit. Masonry, surrounding and decorating the concrete core of the wall, did not bear load. Concrete resisted minor shaking, yielding only to forces higher than fracture limits. Roman building traditions survived the Dark Ages, and 12th century Crusader castles erected in earthquake-prone Syria survive until today in reasonably good condition. Usage of earthquake-resistant technology depends on the perception of earthquake risks and on available financial resources. Earthquake-resistant construction practice is significantly more expensive than regular construction. Frequent earthquakes maintain safe construction practices, like the timber-laced masonry tradition in the Eastern Mediterranean throughout 500 years of political and technological development.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

While seismicity of any area on earth can nowadays be easily measured by instrumental seismology, the quantity, quality, and distribution of the seismograph stations has been more or less sufficient for the purpose during the last 50 years only. Recurrence period of damaging earthquakes is often longer than this, even longer than individual and social memory (Force 2008). To gain information about seismic events one needs to study historical sources (Guidoboni 1993; Guidoboni and Ebel 2009), archaeological evidence (Stiros and Jones 1996), and geological evidence (McCalpin 1996).

Archaeoseismology, the archaeological study of earthquakes is extremely useful for scientists assessing seismic hazards (Sintubin 2013). It is a treasure trove of information about ancient societies. Perception of earthquakes, the risk a society can and will tolerate, the longevity and means of their social memory (Kázmér et al. 2010), expertise of builders to construct buildings which can resist ground shaking, and technology transfer associated with these activities are relevant questions for historical and social sciences.

Another worthwhile direction of research is the role of external forcing factors on human evolution. Recent studies almost invariably focused on climate change and climate-influenced change of vegetation (Maslin and Christensen 2010), while mostly neglecting the effects of seismic and volcanic catastrophes (King and Bailey 2010). An interesting idea of Force and McFadgen (2010) states that there are thirteen Neolithic cultures which later developed into major civilizations (Roman, Etruscan, Corinthian, Mycenaen, Minoan, Tyre, Jerusalem, Niniveh, Ur-Uruk, Mesopotamian, Persian, Mohenjodaro, Aryan India, Memphis in Egypt, and Chinese). One can readily add the Aztec, Maya and Inca cultures along the seismic western margin of the Americas. Putting these on a map of earthquakes it is striking to observe that all of them evolved in close proximity to faults and mountain ranges of high earthquake activity (Jackson 2006). In this study another set of sites is added, arranged along tectonically active zones along the northern margin of the Eurasian mountain range: the belt of settlements and cultures collectively called the Silk Road (Lieu and Mikkelsen 2017).

There is long but somewhat meagre tradition of studying seismic hazard, risk, and resilience of societies along the Silk Road. Earthquakes are parts of nature and life, and people have developed a connection with land throughout millennia (e.g. in Iran: Ibrion et al. 2014; however, the 2003 Bam earthquake arrived to a community not believing it can happen: Parsizadeh et al. 2015). Knowledge of seismicity and the methods used by local people to resist and survive destruction inflicted by natural calamities in general (Janku 2010) and by earthquakes in particular (Jusseret 2014; Rideaud and Helly 2017) are valuable contributions to the understanding how human society works.

Environmental history of the Silk Road has been studied intensively (see papers in the present volume), but earthquake hazard and risk, even when known to exist (Xu et al. 2010), were not systematically considered (Li et al. 2015). An exception is the activity of the team of Korjenkov (later spelled as Korzhenkov) in Central Asia, mostly Kyrgyzstan (Korjenkov et al. 2003, 2006a, b, 2009; Korzhenkov et al. 2016).

While there is a rich literature in China on archaeoseismology of individual buildings (Zhou 2007), on regional studies (Lin et al. 2005; Hong et al. 2014), and of conceptual questions (Hu 1991; Zhang et al. 2001; Shen and Liu 2008) these often lack the necessary detail to support their conclusions. While the ideas put forward are interesting, it is necessary to make a systematic survey of earthquake-damaged buildings and other constructions to improve the seismic hazard assessment of the country. Here an overview is provided of some seismic problems along the overland Silk Road and how these were overcame by various societies during the last two millennia (Fig. 7.1).

Modern land routes (red) of the Silk Road economic belt and sea routes (blue) of the Maritime Silk Road of the 21st Century (Li et al. 2015). Both networks are patterned according to the traditional merchant routes of Antiquity and the Middle Ages

Forlin and Gerrard (2017) reviewed the ways how communities affected by earthquakes behave after the event: the spiritual, constructional, and financial steps taken to restore the community and its property. Here we discuss the preventive measures taken by populations living along the Silk Road, irrespective whether these have been applied consciously or unconsciously, based on tradition only.

2 Seismicity Along the Silk Road

There is a great earthquake and mountain belt that runs from China to Italy. Throughout this region the topography is largely created by fault movement in earthquakes. These faults move as a result of the ongoing collision between the Eurasian plate to the north and the African, Arabian and Indian plates to the south. Settlements are concentrated along the range fronts (Jackson 2006).

The Silk Road, a classical artery of travel, trade and conquest, ran along the southern, mountainous margin Eurasia. It started in the ancient Chinese capital of Xi’an in the east, allowing the transfer of people, goods and ideas into the Middle East, especially to Persia, Baghdad and Anatolia. Connections reached as far as the Greek and Roman world in the Mediterranean. Probably it is not by chance that this caravan route followed the occurrence of springs, rivers, and settlements arranged along the foot of tectonically active mountains. Although certainly being a route of convenience, people and pack animals needed water, food and rest during their travel, and markets to exchange goods. These were provided by mountain-foot springs, by agriculture developed on alluvial fans, and the settlements inhabited by farmers, craftsmen and traders (Jackson 2006).

While most of the Silk Road runs in the temperate and subtropical desert zone, there is ample mountain topography to create orographic rain, and to provide year-round streamflow and perennial springs.

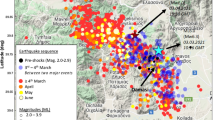

The Indian subcontinent and the Asian continent has been in collision obeying plate tectonic forces for tens of millions of years (Tapponnier and Molnar 1979). This deformation created the Himalayas, the range closest to India, and all the mountain ranges north of it as far as the Altay. As India is still forcing its way into the ‘soft belly’ of Asia, the mountains within are currently being uplifted and displaced in various ways. This active tectonics presents itself repeatedly in the form of catastrophic earthquakes (Fig. 7.2).

Locations of anti-seismic construction practice discussed in the text along the Silk Road. 3D topographic map overprinted by sites of earthquakes (of the magnitude 4.5–7.5 range), which occurred between 1960 and 1980 (red dots) (Espinosa et al. 1981). A Wakamatsu, Japan. B Tianshui, Gansu, China. C Kamenka fortress, Issyk-kul, Kyrgyzstan. D Tossor, Issyk-kul, Kyrgyzstan. E Burana, Kyrgyzstan. F Palmyra, Syria. G Al-Marqab, Baniyas, Syria. H Safita, Syria. J Safranbolu, Turkey. K Istanbul, Turkey. L Athens, Greece. M Elbasan, Albania

So the mountains are both beneficial to their inhabitants: providing rainfall, storing water, and at the same time fatally dangerous: producing earthquakes and other natural calamities. It is a well-calculated decision of societies to live there or abandon these places. It seems that humans prefer to take risks, and—considering the benefits—do not mind to live in areas regularly destroyed by catastrophic earthquakes. In this paper methods are examined on how people counter seismic destruction of their buildings, and the evidence on people’s understanding and misunderstanding of these life-threatening natural processes.

3 Archeoseismology and Other Seismologies

The way we recognize and understand earthquakes is in tremendous change nowadays. There are digital instruments worldwide to receive seismic signals globally, and internet-connected computers automatically calculate the place, depth, and magnitude of earthquakes. This has been going on for not more than twenty years. Before that individual seismometers have been recording earthquakes for up to a hundred years. This is enough to understand the major seismic patterns of the earth, but not enough to be prepared for major earthquakes, especially in areas where these occur rarely.

The bigger an earthquake, the more rarely it occurs again at the same place. This recurrence period is often longer than the period covered by data of seismographs. To understand seismicity of the pre-instrumental period one must refer to historical documents: it is a scientific field called historical seismology (Guidoboni and Ebel 2009). A few centuries, rarely millennia can be more or less covered by these data. Where historical records are missing, there might be evidence preserved in ancient monuments. The way these were damaged by earthquakes is studied by archaeoseismology (Stiros and Jones 1996). Earthquakes recurring beyond these millennial intervals are studied by paleoseismology, theoretically into millions of years of Earth history (McCalpin 1996).

Seismicity of the past has been studied in detail on both ends of the Silk Road. Japanese historical earthquake catalogues have been reviewed by Ishibashi (2004). In China there are multiple catalogues available (Academia Sinica 1956; Li 1960; for a modern treatment of philological depth see Walter 2016). There are two recent catalogues in the Mediterranean region (Ambraseys 2009; Guidoboni and Comastri 2005). Between them there is the area covered by the catalogue of Ambraseys and Melville (1982) on Persian earthquakes, and historical catalogue of Kondorskaya and Shebalin (1982) of earthquakes in the former Soviet Union. The latter covers much of the Central Asian sector of the Silk Road.

4 Construction Materials in Earthquake-Resistant Techniques

Materials used in permanent and semi-permanent construction varies according to purpose, availability, financial resources, cultural and climatic influences. Adobe, brick, wood, stone, concrete, and metal reinforcements are discussed below. Our knowledge of past construction practices are limited by preservation: adobe is the worst, wood is second, while monumental stone masonry and Roman concrete has the best potential to be preserved for future generations and for the inquisitive eyes of the researcher. Finances determine permanence of buildings, therefore rural construction has the least chance to survive, urban dwellings stand in the middle, and secular and religious monumental constructions are the best to resist destruction of passing millennia.

In respect of anti-seismic construction practices monumental buildings provide the best examples. These are built from the best material, even if it had to be transported from faraway locations at high expenses. The best architects and builders were hired so that the building would last for eternity. Usually high cultures were able to build these at the height of their power.

These cultures—flourishing at opposite ends of the Eurasian continent—used a variety of construction techniques, hampering comparison of the earthquake-resistant construction practices. China did not use the marble columns of Greece and Rome, neither masonry arches invented by the Romans. Instead, a combination of wood and brick masonry was often used in ways not found in the Mediterranean. Italy extensively used metal anchors to hold together buildings already damaged by earthquakes (Forlin and Gerrard 2017); this method was not seen towards the east.

4.1 Yurt

Timber-framed felt tents (Turkish yurt, Mongolian ger) have been the preferred housing of nomadic shepherds of Asia, probably for millennia (Fig. 7.3). Being lightweight, it can be dismantled, transported and re-erected by two persons in a matter of hours. It provides excellent indoor temperature and ventilation in summer, and tolerable protection against winter frost. Protects the people and their property inside from rainfall, snowfall, and from strong winds. It is still in use today both in rural and in urban environment. A rarely considered property of the yurt is being totally earthquake-resistant. One of the largest intracontinental earthquakes, the 1957 Gobi-Altay earthquake (M = 8.3) ruptured the crust over a length of 260 km, causing elevation differences over 7 m. However, despite the enormous energy released, no casualty was reported after the event (Kurushin et al. 1997). Although the affected area is considered uninhabited, it is far from that. Permanent villages and farm-like semi-permanent settlements, both consisting of yurts, are scattered widely. Neither vertical nor horizontal ground displacements caused by passing seismic waves did any reported harm to yurts.

Mongolian yurt (ger) in the Gobi, Mandalgovi, Mongolia. Photo: Mark Fischer. Creative Commons licence. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Mongolian_Ger.jpg. Accessed January 30, 2018

4.2 Rammed Earth, Adobe

Rammed earth is an ancient construction technique. Clay, silt and sand are compacted and rammed into removable formwork (Figs. 7.4, 7.5, 7.6 and 7.7). The resultant wall and single-floor buildings constructed this way have good vertical load-bearing capacity (Jaquin 2008). In case of frequent horizontal forces caused by earthquakes it is reinforced by hatil-style wooden boards (see under Wood-reinforced masonry below) (Ortega et al. 2014). It is excellent heat insulator both in winter and in summer. Another advantage is that it can be built and restored cheaply. Rammed earth is a frequently used construction material in vernacular architecture. Monumental and military architecture uses rammed earth and adobe brick buildings in Central Asia (e.g. Chuy, Kyrgyzstan: Korjenkov et al. 2012; also in Bam, Iran: Zahrai and Heidarzadeh 2007).

Aerial image of the earthworks of Medieval Kamenka fortress north of Issyk Kul, Kyrgyzstan. The rhomb-shaped fortress, surrounded by towers, is cross-cut by an active fault (marked with arrows), which caused 4 m left-lateral displacement during the M 8.2 Kemin earthquake in 1911. Rammed earth walls survived with minor damage (Korjenkov et al. 2006a, Povolotskaya et al. 2006)

Northwestern wall of Medieval Kamenka fortress. In the front: trenched cross-section of rammed earth wall. Background: 4 m displacement caused by a the left-lateral fault activated in the 1911 earthquake [Photo M. Kázmér, #1178 (Serial numbers of photographs refer to the Archaeoseismology Database (ADB), currently being built at Eötvös University, Budapest (Moro and Kázmér 2018)]

Rammed earth wall of Tossor fortress (Lake Issyk Kul, Kyrgyzstan) as seen in excavation trench cross-cutting the buried wall. Layers are marked by horizontal scratches made by the excavating archaeologist. Three ruptures dissect the wall. Trench is 2.5 m deep (Photo M. Kázmér, #1246). For details see Korzhenkov et al. (2016)

4.3 Wood

Wood is the ultimate earthquake-resistant construction material (Fig. 7.8). Its flexibility allows to accept moderate horizontal load. The relatively cheap construction allows quick reconstruction in case of damage. In earthquake-prone Japan most of the traditional buildings, from the monumental to the vernacular, are made of wood. Therefore practically there is no way to do archaeoseismological studies, because evidence—even if only a few decades old—has not been preserved (Barnes 2010). If seismic destruction happens, it is always immediately repaired, at least during the past 1500 years.

4.4 Wood-Reinforced Masonry

Hımış and hatil method of wood reinforcement of brick and stone masonry houses, especially in Greece, Turkey and in the Pakistani and Indian Himalayas are repeatedly discussed (Porphyrios 1971; Gülkan and Langenbach 2004; Langenbach 2007) emphasizing the beneficial effects of flexible wood columns, beams, and crossbars embedded in an otherwise brittle masonry structure (Figs. 7.9, 7.10, 7.11 and 7.12).

Timber frame with masonry infill in a residential building in the Buddhist monastery at Tianshui, Gansu, China. This structure is extremely resistant to earthquakes: well-jointed columns and beams maintain structural integrity, although masonry infill might get loose under strong seismic shaking (Photo M. Kázmér, #3068)

Horizontal timber embedded in load-bearing wall masonry (hatıl construction). Wooden boards, when tied around the facade-side wall junctions aid in reducing the occurance of corner wedge failures. These horizontal boards accept lateral loads during seismic shaking (Dogangün et al. 2006). Elbasan, Albania (Photo M. Kázmér, #8769)

Source https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Safranbolu_traditional_house_1.jpg. Creative Commons license. Accessed September 23, 2017

Timber-laced masonry house in Safranbolu, Turkey (hımış construction). The ground floor is unreinforced masonry, followed by two floors of intricate timber structure. Note oblique timbers at corners, providing support against lateral shaking. Photo Uğur Başak.

In general, all timber-framework houses are based on the same structural principle: the wooden structural system bears mainly the horizontal loads while either the masonry or timber columns support the gravity loads (Dutu et al. 2012). The variety of framework geometries applied are practically unlimited. However, the simplest buildings, like a vernacular house in the city of Elbasan in Albania (Fig. 7.10), having only horizontal boards embedded in masonry (hatil construction) increases the resistance of the buildings to horizontal loads, i.e. lateral shaking by seismic waves. Niyazov (2012) provided a concise report on how both adobe and masonry vernacular buildings are routinely reinforced with wooden beams im Tajikistan. The European (Mediterranean) historical practice was reviewed by Dutu et al. (2012).

4.5 Brick Bands

Byzantine monumental buildings built from the 5th to the 15th century are easily recognized by a conspicuous banding of horizontal red brick layers, repeatedly emplaced within an otherwise fully stone masonry wall (Figs. 7.13, 7.14 and 7.15). These brick layers were laid across the width of the 5 m wide Theodosian walls of Constantinople (Istanbul) (Ahunbay and Ahunbay 2000). While the exact engineering role of this banded construction is not well understood, it is considered as hatil, i.e. a monumental analogue of the horizontal wooden boards (Homan 2004). An interesting experience of the 1999 earthquake was that recently restored walls, where the brick banding was used for decorative purposes only, collapsed, while adjacent ancient walls did not (Langenbach 2007).

Alternating layers of brick and stone masonry. Early 5th century Theodosian wall, Istanbul, Turkey. There are seven courses of brick bands laid at intervals, running through the entire thickness of the wall (see Fig. 7.14) (Ahunbay and Ahunbay 2000). The brick layers are considered to be antiseismic constructions (Photo M. Kázmér, #0279)

Burana minaret (10–11th century; Kyrgyzstan), before restoration. It was probably damaged by late Medieval earthquake, removing more than half of the originally 46 m high tower, leaving only a 18 m high portion standing (Korjenkov et al. 2006a, b). Note alternating layers of different bricks: this construction practice is similar to Persian-Byzantine brick-stone masonry (Photo of local postcard, #1084)

4.6 Metal Clamps, Bolts, Anchors and Chains

Iron ingots hold together carefully hewn masonry of a seawall in Hangzhou Bay dated to the Ming and Qing dynasties (Wang et al. 2012). Whether this technology, well-known in Greek architecture of Antiquity, was widely applied in China is a matter of further research. The use of cast iron—of as yet unknown metallurgical characteristics—would certainly raise eyebrows of any modern engineer. The Greeks never used it; they used steel instead, surrounded by lead to protect rusting and to dampen the eventual collision of metal and the embedding stone during earthquake (Stiros 1995, 1996). Metal clamps and dowels were used in construction of the Parthenon in Athens, Greece (Fig. 7.16) and in the Baal temple of Palmyra, Syria (Figs. 7.17 and 7.18). Elastic steel provided strength, while plastic lead casing absorbed minor shifts of blocks without fracturing rigid stone.

There is a widely used method in Italy to reinforce a building moderately damaged by earthquake. Opposite walls are clamped together tightly by smith’s iron rods (anchors), often ending in decoratively shaped crossbars (Forlin and Gerrard 2017) (Fig. 7.19).

4.7 Interlocking Masonry

A spectacular element of Islamic architecture is the widespread use of interlocking masonry in arches. The example shown is an ‘arch’ constructed of interlocking masonry arches (Fig. 7.20), functioning as lintel. During seismic excitation alternating in-plane extension and compression allows elements of arch masonry to drop, ultimately leading to collapse. Interlocking masonry prevents vertical displacement of arch stones. Doubts can be raised whether the technology is a strictly Islamic development, although it is most widely used there. In the ruined city of 6th century Zenobia (Halabiyya, Syria)—rebuilt at that time by the Byzantine emperor Justinian—there are lintels composed of interlocking masonry (Fig. 7.21). However, Crusader castles of 11–13th century along the Mediterranean coastal region do not use this technique, despite being in close contact with Islamic culture.

4.8 Roman Concrete

Most walls of al-Marqab citadel in coastal Syria, both Crusader and Muslim, are one of two types: either stone masonry or opus caementitium, i.e., “Roman concrete” (Lamprecht 2001) or “ancient concrete” (Ferretti and Bažant 2006). Stone masonry is characterized by dressed stones, hewn rectangular and of standard size, with or without mortar, always without metal anchors. Arches, domes, thick walls routinely have been constructed this way.

Roman concrete or ancient concrete is a mixture of sand, lime, and stone rubble. It is very similar to modern concrete in appearance. Invented by the Romans, the technique survived well into the Middle Ages. Opus caementitium is often combined with traditional masonry, where an outer, visible layer of variously dressed blocks was erected with mortar. This external, regular masonry work served during construction as a mold for casting the core. Poured material served for the inner, invisible parts of the wall (Figs. 7.22 and 7.23) (Ferretti and Bažant 2006; Mistler et al. 2006). Masonry both served aesthetic demands and provided a hard, protective layer to counter weather effects and enemy attacks. This layer often served as framework during concrete pouring only, having no supporting function when concrete hardened. Walls and vaults of variable thickness, from a few decimetres up to 5 m thickness, were constructed this way (Kázmér and Major 2010). Buildings constructed of Roman concrete are extremely resistant to natural calamities: the Pantheon of Rome, having a dome of 60 m diameter, was cast as monolithic building. It has been standing practically intact for the past two millennia.

5 Discussion

5.1 Social Memory of Calamities

As we learned from Jackson (2006) “it is the fault that provides the water, but the fault may kill you when it moves”. The relatively minor agricultural and trading settlements developed along the Silk Road in the past millennia are vulnerable to earthquake destruction. However, even if human fatalities can reach sizeable proportion of the inhabitants (Jackson 2006), these often come infrequently, beyond the length of individual and social memory. There is very little research on the longevity of social memory; we can assess with confidence that it probably lasts at least for three generations (from grandparents to grandchildren). Longer memory can be assured if and where religious practice or taboo is associated. Repeat times of earthquakes on individual faults are likely to be measured in hundreds or thousands of years and they are most unlikely to recur on a timescale relevant for human memory (Jackson 2006).

One is ready to consider a natural calamity (in our case the earthquake) as root cause of devastation and loss. As it has been recognized in social sciences some time ago, a catastrophe is a trigger mechanism only, which releases a disaster that was waiting to occur, due to deep-rooted social causes (Degg and Homan 2005). A similarly high-magnitude earthquake which causes neither loss of life, nor material damage in Mongolia (the Gobi-Altay Mw8.1 earthquake in 1957), can cause fatalities well into the hundreds of thousands in China (the Tangshan M7.5 earthquake in 1977), not only because population density is so much higher in the latter, but because of inappropriate construction methods.

5.2 Anti-seismic Construction Practices

Timber structures and timber-reinforced masonry and adobe structures have been in use all along the Silk Road from China to the Mediterranean for millennia (Semplici and Tampone no date). Whether their use is the result of parallel innovation or spread of good practices either east or west, is a matter of research in progress. Detailed study on fitting of beams and columns, for example, might help to recognize independent or dependent development of life-saving construction practices.

Monumental buildings are the best for the study of anti-seismic construction methods. These, especially the religious buildings were created for eternity. The best material was used, even if transported from faraway location. The best workmanship was applied. From site selection to construction and to subsequent maintenance probably the best conditions existed.

Some construction methods are characteristic for certain civilizations only. E.g. marble and sandstone columns are typical for Greek and Roman monumental architecture. These columns, especially if made of multiple drums, are kind of seismoscopes, i.e. simple earthquake-sensing devices, being easily deformed by earthquakes. As China did not use these stone columns, an important archaeoseismological evidence is inherently missing there.

5.3 Earthquake-Resistant Construction Without Apparent Need

While Palmyra (Tadmor, Syria) is not particularly active seismically (Sbeinati et al. 2005), the use of lead-enclosed metal dowels and clamps in the 2000 years old Nabatean Baal temple shows high knowledge of anti-seismic construction methods. We are aware of three Greeks, one of them an architect, who worked on the construction (Stoneman 1994). This construction method probably was developed in Greece, which is the seismically most active part of the Alpine-Himalayan mountain belt (Tsapanos 2008). It is possible that architects of the era carried their experiences from the homeland to faraway territories, transferring essential knowledge of earthquake resistant construction, and routinely applied it to the monumental architecture they created.

5.4 Traditional Good Practices and Modern Construction

One of the construction materials discussed invites an important remark. Wood-reinforced masonry is at least as good as modern steel-frame and reinforced concrete (RC) buildings, and the chance of survival for their inhabitants is often higher, as engineering studies of modern earthquakes show. The reason is not necessarily that RC is inferior; it can be designed and produced to be earthquake-resistant. The problem is the uneducated, unregulated and uncontrolled construction industry in the rapidly growing developing countries overlapping major seismic zones worldwide. In this situation traditional construction practices of vernacular architecture are better, more reliable than the RC construction in need of sorely lacking construction skills (Langenbach 2015).

The importance of engineers’ understanding and appreciation of vernacular construction practices cannot be overestimated (Dixit et al. 2004). Portugal, since the tragic 1755 Lisbon earthquake, has been in the forefront of developing earthquake-resistant construction practices, contributing to the awareness of the local seismic culture (Correia et al. 2014). There was even an European centre for studying traditional anti-seismic practices based on archaeological approach (Helly 1995). Application of good practices learned from local seismic cultures would significantly reduce vulnerabilty of communities living in earthquake-prone areas (Karababa and Guthrie 2007).

Although experts agree that wooden framework buildings resist earthquakes very well, the presence of ancient timber-framework buildings does not indicate an earthquake-prone area. Where wood is available, and local tradition and builders are at hand, this construction method is widely applied (see the German and Austrian Fachwerk construction) (Bostenaru Dan 2014).

Systematic use or disuse of known earthquake-resistant techniques in any society depends on the perception of earthquake risk and on available financial resources. Earthquake-resistant construction practice is significantly more expensive than regular construction. Perception is influenced mostly by short individual and longer social memory. If earthquake recurrence time is longer than the preservation of social memory, if damaging quakes fade into the past, societies commit the same construction mistakes again and again. Longevity of the memory is possibly about one to three generations’ lifetime, i.e. less than 100 years. Events occurring less frequently can be readily forgotten, and the risk of recurrence considered as negligible, not worth the costs of safe construction practices. Frequent earthquakes maintain safe construction practices, like the timber-laced masonry tradition in the Eastern Mediterranean throughout 500 years of political and technological development.

6 Conclusions

Archaeoseismology, the archaeological study of past earthquakes, is a treasure trove of information about the behaviour of ancient societies. Earthquakes are part of nature and life along the overland Silk Road between China and the Mediterranean; peoples developed various methods to cope with the risk. Making buildings able to resist the shaking of the ground and knowing ways of quick reconstruction after destruction depend on available material and knowledge of good construction practices.

Materials used in permanent and semi-permanent construction vary according to purpose, availability, financial resources, cultural and climatic influences. Mostly adobe, brick, wood, stone, ancient concrete, and metal reinforcements were applied for earthquake-resistant construction. Rammed earth houses can be built and restored quickly and cheaply. Wood is the ultimate earthquake-resistant construction material: it can resist seismic shaking and allows quick reconstruction in case of damage. Wood-reinforced masonry provides flexible support to masonry buildings. Brick layers laid within stone masonry walls provide additional flexibility during shaking. Metal dowels, clamps, bolts, anchors and chains provide minor but essential support of structures in case of moderate earthquakes. Interlocking masonry prevents vertical displacement of arch stones. Roman concrete, rubble cemented by lime and additives is another excellent construction material for anti-seismic purposes. Our knowledge of past construction practices are limited by preservation: adobe is the worst material for long-term survival, wood is second, while monumental stone masonry and Roman concrete has the best potential to be preserved for millennia.

Architects of the era carried their experience from the homeland to faraway territories, transferring essential knowledge of earthquake resistant construction. They routinely applied anti-seismic techniques even far away from seismically active faults. Application of good practices learned from local seismic cultures would significantly reduce vulnerability of communities living in earthquake-prone areas. Knowledge of seismicity and the local methods used to resist and survive destruction are valuable contributions to understand how society works.

References

Academia Sinica. (1956).

Zhongguo Dizhen Ziliao Nianbiao. Chronological Tables of Earthquake Data of China, 1–2.

Zhongguo Dizhen Ziliao Nianbiao. Chronological Tables of Earthquake Data of China, 1–2.

Zhongguo Kexueyuan Dizhen Gongzuo Weiyuanhui Lishizu Bianji. Chinese Academy of Science Working Committee on Earthquake History Editing Team (Ed.). 科学出版社出版 Kexue Chubanshe Chuban. Science Press, Beijing.

Zhongguo Kexueyuan Dizhen Gongzuo Weiyuanhui Lishizu Bianji. Chinese Academy of Science Working Committee on Earthquake History Editing Team (Ed.). 科学出版社出版 Kexue Chubanshe Chuban. Science Press, Beijing.Ahunbay, M., & Ahunbay, Z. (2000). Recent work on the land walls of Istanbul: Tower 2 to Tower 5. Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 54, 227–239.

Ambraseys, N. (2009). Earthquakes in the Mediterranean and the Middle East: A multidisciplinary study of seismicity up to 1900 (p. 968). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ambraseys, N., & Melville, C. P. (1982). A history of Persian earthquakes (p. 219). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Barnes, G. L. (2010). Earthquake archaeology in Japan: An overview. In M. Sintubin, I. Stewart, T. M. Niemi, & E. Altunel, (Eds.) Ancient Earthquakes (pp. 81–96). Geological Society of America Special Paper, 471.

Bostenaru Dan, M. (2014). Timber frame historic structures and the local seismic culture - An argumentation. In M. Bostenaru Dan, J. Armas, & A. Goretti (Eds.), Earthquake hazard impact and urban planning (pp. 213–230). Berlin: Springer.

Correia, M., Carlos, G., Rocha, S., Lourenco, P. B., Vasconcelos, G., & Varum, H. (2014). Seismic-V: Vernacular seismic culture in Portugal. In M. Correia, G. Carlos, & S. Rocha (Eds.), Vernacular heritage and earthen architecture: Contributions for sustainable development (pp. 663–668). London: Taylor & Francis.

Degg, M., & Homan, J. (2005). Earthquake vulnerability in the Middle East. Geography, 90, 54–66.

Dixit, A. M., Parjuli, Y. K., & Guragain, R. (2004). Indigenous skills and practices of earthquake resistant construction in Nepal. In 13th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering Vancouver, B.C., Canada, August 1–6, 2004, Paper No. 2971, 6 p.

Dogangün, A., Tuluk, Ö. I., Livaoglu, R., & Acar, R. (2006). Traditional wooden buildings and their damages during earthquakes in Turkey. Engineering Failure Analysis, 13, 981–996.

Dutu, A., Gomes Ferreira, J., Guerreiro, L., Branco, F., & Goncalves, A. M. (2012). Technical note: Timbered masonry for earthquake resistance in Europe. Materiales de Construcción, 62, 615–628.

Espinosa, A. F., Rinehart, W., & Tharp, M. (1981). Seismicity of the Earth 1960–1980. https://www.reddit.com/r/MapPorn/comments/55l5uh/seismicity_of_the_earth_19601980_2182_x_1200/. Accessed September 18, 2017.

Ferretti, D., & Bažant, Z. P. (2006). Stability of ancient masonry towers: Stress redistribution due to drying, carbonation and creep. Cement and Concrete Research, 36, 1389–1398.

Force, E. R. (2008). Tectonic environments of ancient civilizations in the Eastern Hemisphere. Geoarchaeology, 23, 644–653.

Force, E. R., & McFadgen, B. G. (2010). Tectonic environments of ancient civilizations: Opportunities for archaeoseismological and anthropological studies. In M. Sintubin, I. Stewart, T. M. Niemi, & E. Altunel, (Eds.), Ancient Earthquakes (pp. 21–28). Geological Society of America Special Paper, 471.

Forlin, P., & Gerrard, C. M. (2017). The archaeology of earthquakes: The application of adaptive cycles to seismically-affected communities in late medieval Europe. Quaternary International, 446, 95–108.

Guidoboni, E. (1993). The contribution of historical records of earthquakes to the evaluation of seismic hazard. Annali di Geofisica, 36, 201–215.

Guidoboni, E., & Comastri, A. (2005). Catalogue of Earthquakes and Tsunamis in the Mediterranean Area from the 11th to the 15th Century. Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, Roma; Storia Geofisica Ambiente (INGV-SGA), Bologna, Italy, 1037 p.

Guidoboni, E., & Ebel, J. E. (2009). Earthquakes and tsunamis in the past. A guide to techniques in historical seismology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gülkan, P., & Langenbach, R. (2004). The earthquake resistance of traditional timber and masonry dwellings in Turkey. In 13th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering Vancouver, B.C., Canada, August 1–6, 2004, Paper No. 2297, 15 p.

Helly, B. (1995). Local seismic cultures: A European research program for the protection of traditional housing stock. Annali di Geofisica, 38, 791–794.

Homan, J. (2004). Seismic cultures: myth or reality? In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Post-Disaster Reconstruction: Planning for Reconstruction, Coventry, U.K., April 22–23 2004.

Hong, H., Shi, Y., Liu, T., Wang, H., & Zhan, X. (2014). Investigation and analysis of earthquake damage to ancient buildings induced by Lushan earthquake. Earthquake Engineering and Engineering Dynamics, 2014, 147–155.

Hu, S. (1991). The earthquake-resistant properties of Chinese traditional architecture. Earthquake Spectra, 7, 355–389.

Ibrion, M., Lein, H., Mokhtari, M., & Nadim, F. (2014). At the crossroad of nature and culture in Iran: The landscapes of risk and resilience of seismic space. International Proceedings of Economics Development and Research, 71, 38–44.

Ishibashi, K. (2004). Status of historical seismology in Japan. Annals of Geophysics, 47, 339–368.

Jackson, J. (2006). Fatal attraction: Living with earthquakes, the growth of villages into megacities, and earthquake vulnerability in the modern world. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, 364, 1911–1925.

Janku, A. (2010). Towards a history of natural disasters in China: The case of Linfen County. The Medieval History Journal, 10, 267–301.

Jaquin, P. A. (2008). Analysis of historic rammed earth construction (Ph.D. thesis). Durham University, 242 p. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/2169/. Accessed September 25, 2017.

Jusseret, S. (2014). Earthquake archaeology: A future in ruins? Journal of Contemporary Archaeology, 1, 277–286.

Karababa, F., & Guthrie, P. (2007). Vulnerability reduction through local seismic culture. In IEEE Technology and Society Magazine (pp. 30–41). February 2007.

Kázmér, M., & Major, B. (2010). Distinguishing damages of two earthquakes – archeoseismology of a Crusader castle (Al-Marqab citadel, Syria). In Sintubin, M. Stewart, I., Niemi, T., & Altunel, E. (Eds.) Ancient Earthquakes (pp. 186–199). Geological Society of America Special Paper, 471.

Kázmér, M., Major, B., Hariyadi, A., Pramumijoyo, S., & Haryana, Y. D. (2010). Living with earthquakes – development and usage of earthquake-resistant construction methods in European and Asian Antiquity. Geophysical Research Abstracts, 12, EGU2010-14244.

King, G. C. P., & Bailey, G. N. (2010). Dynamic landscapes and human evolution. In M. Sintubin, I. Stewart, T. M. Niemi, & E. Altunel, (Eds.), Ancient Earthquakes (pp. 1–19). Geological Society of America Special Paper, 471.

Kondorskaya, N. V., & Shebalin, N. V. (1982). New catalog of strong earthquakes in the USSR from ancient times through 1977 (p. 608). Boulder, Colorado: World Data Center for Solid Earth Geophysics.

Korjenkov, A., Baipakov, K., Chang, C., Peshkov, Y., & Savelieva, T. (2003). Traces of ancient earthquakes in medieval cities along the Silk Road, northern Tien Shan and Dzhungaria. Turkish Journal of Earth Sciences, 12, 241–261.

Korjenkov, A. M., Arrowsmith, J. R., Crosby, C., Mamyrov, E., Orlova, L. A., Povolotskaya, I. E., et al. (2006a). Seismogenic destruction of the Kamenka medieval fortress, northern Issyk-Kul region, Tien-Shan, Kyrgyzstan. Journal of Seismology, 10, 431–442.

Korjenkov, A. M., Michajljow, W., Wetzel, H.-U., Abdybashaev, U., & Povolotskaya, I. E. (2006b). International Training Course “Seismology and Seismic Hazard Assessment”. Bishkek, 2006. Field Excursions Guidebook, Bishkek-Potsdam, 112 p.

Korjenkov, A. M., Tabaldiev, K. S., Bobrovskii, A. V., Bobrovskii, A. V., Mamyrov, E. M., & Orlova, L. A. (2009). A macroseismic study of the Taldi-Sai caravanserai in the Kara-Bura river valley (Talas Basin, Kyrgyzstan). Russian Geology and Geophysics, 50, 63–69.

Korjenkov, A. M., Kolchenko, V. A., Rott, P. G., & Abdieva, S. V. (2012). Strong medieval earthquake in the Chuy Basin, Kyrgyzstan. Geotectonics, 46, 313–314.

Korzhenkov, A. M., Kolchenko, V. A., Luzhanskii, D. V., Abdieva, S. V., Deev, E. V., Mazeika, J. V., et al. (2016). Archaeoseismological studies and structural position of the medieval earthquakes in the south of the Issyk-Kul depression (Tien Shan). Izvestiya, Physics of the Solid Earth, 52, 218–232.

Kurushin, R. A., Bayasgalan, A., Ölzybat, M., Entuvshin, B., Molnar, P., Bayarsayhan, Ch., et al. (1997). The surface rupture of the 1957 Gobi-Altay earthquake. Geological Society of America Special Paper, 320, 1–145.

Lamprecht, H.-O. (2001). Opus caementitium—Bautechnik der Römer: Köln, Römisch-Germanisches Museum & Düsseldorf. Bau + Technik Verlag, 264 p.

Langenbach, R. (2007). From “opus craticium” to the “Chicago frame”: Earthquake-resistant traditional construction. International Journal of Architectural Heritage, 1, 29–49.

Langenbach, R. (2015). The earthquake resistant vernacular architecture in the Himalayas. Seismic retrofitting. In M. Correia, P. B. Lourenço, & H. Varum (Eds.), Learning from Vernacular Architecture (pp. 83–92). London: Taylor & Francis.

Li, P., Qian, H., Howard, K. W. F., & Wu, J. (2015). Building a new and sustainable “Silk Road economic belt”. Environmental Earth Science, 74, 7267–7270.

Li, S. (Ed.). (1960). Catalogue of Chinese Earthquakes. Beijing: Science Press.

(1960). 中国地震目录 第1集, 科学出版社, 北京.

(1960). 中国地震目录 第1集, 科学出版社, 北京.Lieu, S., & Mikkelsen, G. (Eds.). (2017). Between Rome and China: History, religions and material culture of the silk road. Begijnhof: Silk Road Studies 18. Brepols.

Lin, J. S., Lin, Z. J., & Chen, J. F. (2005). The ancient great earthquake and earthquake-resistance of the ancient buildings (towers, temples, bridges) in Quanzhou city. World Information on Earthquake Engineering, 21, 159–166.

Maslin, M. A., & Christensen, B. (2010). Tectonics, orbital forcing, global climate change, and human evolution in Africa: Introduction to the African paleoclimate special volume. Journal of Human Evolution, 53, 443–464.

McCalpin, J. P. (1996). Paleoseismology (p. 588). New York: Academic Press.

Mistler, M., Butenweg, C., & Meskouris, K. (2006). Modelling methods of historic masonry buildings under seismic excitation. Journal of Seismology, 10, 497–510.

Moro, E., Kázmér, M. (2018): Damage in ancient buildings - towards an archaeoseismological database. In 9th International INQUA Meeting on Paleoseismology, Active Tectonics and Archeoseismology (PATA), June 25–27, 2018, Possidi, Greece (in press).

Niyazov, J. (2012). Antiseismism in the traditional architecture of Tajikistan. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Complexity in Earthquake Dynamics (pp. 150–155). Tashkent: Turin Polytechnic University.

Ortega, J., Vasconcelos, G., & Correia, M. (2014). An overview of seismic strengthening techniques traditionally applied in vernacular architecture. In 9th International Masonry Conference 2014 in Guimarães (pp. 1–12).

Parsizadeh, F., Ibrion, M., Mokhtari, M., Lein, H., & Nadim, F. (2015). Bam 2003 earthquake disaster: On the earthquake risk perception, resilience and earthquake culture – cultural beliefs and cultural landscape of Qanats, gardens of Khorma trees and Argh-e Bam. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 14, 457–469.

Porphyrios, D. T. G. (1971). Traditional earthquake-resistant construction on a Greek island. Journal of the Society of Architecture Historians, 30, 31–39.

Povolotskaya, I. E., Korjenkov, A., Crosby, C., Mamyrov, E., Orlova, L., Tabaldiev, K., & Arrowsmith, R. (2006). A use of the archeoseismological method for revealing traces of strong earthquakes, on example of the Kamenka medieval fortress, northern Issyk-Kul region, Tien Shan. In P. Kadyrbekova, & A, M. Korjenkov, (Eds.), Materials of the 1st International Conference Humboldt-Colleagues in Kyrgyzstan “Heritage of Alexander von Humboldt in the studies of the mountain regions” (pp. 164–174). Bishkek: Ilim Press.

Rideaud, A., & Helly, B. (2017). Ancient buildings and seismic cultures: The cases in Armenia. In 42nd International Commission on the History of Geological Sciences (INHIGEO) Symposium (p. 139), Yerevan, Armenia. Abstracts and Guidebook.

Sbeinati, M. R., Darawcheh, R., & Mouty, M. (2005). The historical earthquakes of Syria: An analysis of large and moderate earthquakes from 1365 B.C. to 1900 A.D. Annals of Geophysics, 48, 347–435.

Semplici, M., & Tampone, G. (no date). Timber structures and architectures in Seism Prone areas included in the UNESCO world heritage list (progress report). http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.542.3119&rep=rep1&type=pdf. Accessed March 6, 2018.

Shen, Z. G., & Liu, H. X. (2008). Exploration of philosophical thought in earthquake resistant structure of Chinese ancient architecture. Beijing, China: Studies in Dialectics of Nature.

Sintubin, M. (2013). Archaeoseismology. In M. Beer, E. Patelli, I. Kouigioumtzoglou, & I. S.-K. Au. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Earthquake Engineering (7 p., 18 figs.), Berlin: Springer.

Stiros, S. C. (1995). Archaeological evidence of antiseismic constructions in Antiquity. Annali di Geofisica, 38, 725–736.

Stiros, S. C. (1996). Identification of earthquakes from archaeological data: Methodology, criteria, and limitations. In S. C. Stiros, & R. E. Jones, (Eds.), Archaeoseismology (pp. 129–152). British School at Athens, Fitch Laboratory Occasional Paper 7.

Stiros, S. C., & Jones, R. E. (Eds.). (1996). Archaeoseismology. British School at Athens, Fitch Laboratory Occasional Paper 7.

Stoneman, R. (1994). Palmyra and its empire: Zenobia’s revolt against Rome (p. 265). Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

Tapponnier, P., & Molnar, P. (1979). Active faulting and Cenozoic tectonics of the Tien Shan, Mongolia and Baykal regions. Journal of Geophysical Research, 84, 3425–3459.

Tsapanos, T. M. (2008). Seismicity and seismic hazard in Greece. In E. S. Huyebye (Ed.), Earthquake monitoring and seismic hazard mitigation in Balkan countries (pp. 253–270). Dordrecht: Springer Science.

Walter, J. (2016). Erdbeben im antiken Mittelmeerraum und im frühen China. Eine vergleichende Analyse der gesellschaftlichen Konstruktion von Naturkatastrophen bis zum 3. Jahrhundert n.Chr (Ph.D. thesis). Fakultät für Geschichte, Kunst- und Orientwissenschaften der Universität Leipzig, 184 p.

Wang, L., Xie, Y., Wu, Y., Guo, Z., Cai, Y., Xu, Y., et al. (2012). Failure mechanism and conservation of the ancient seawall structure along Hangzhou Bay, China. Journal of Coastal Research, 28, 1393–1403.

Xu, X., Yeats, R. S., & Yu, G. B. (2010). Five short historical earthquake surface ruptures near the Silk Road, Gansu Province, China. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 100, 541–561.

Zahrai, S. M., & Heidarzadeh, M. (2007). Destructive effects of the 2003 Bam earthquake on structures. Asian Journal of Civil Engineering (Building and Housing), 8, 329–342.

Zhang, P. C., Zhao, H. T., Xue, J. Y., & Gao, D. F. (2001). Thoughts of earthquake resistance in Chinese ancient buildings. World Information on Earthquake Engineering, 17, 1–6.

Zhou, Q. (2007). Study on the antiseismic constitution of Shen-Wu gate in the Palace Museum. Earthquake Resistant Engineering and Retrofitting, 29, 81–98.

Acknowledgements

The author is indebted to the following colleagues for help and advice during field work: Zeynep Ahunbay (Istanbul, Turkey), Keyan Fang (Fuzhou, China), Andrey Korzhenkov (Moscow, Russia), Balázs Major (Piliscsaba, Hungary), Ernest Moro (Padova, Italy), Oki Sugimoto (Tsukuba, Japan). Financial help of a CEEPUS scholarship to Tirana (Albania) and of the Syro-Hungarian Archaeological Mission (SHAM) is sincerely acknowledged. Two anonymous reviewers and the editors are gratefully acknowledged for their detailed comments, which significantly improved the manuscript. This is SHAM publication nr. 72.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Kázmér, M. (2019). Living with Earthquakes along the Silk Road. In: Yang, L., Bork, HR., Fang, X., Mischke, S. (eds) Socio-Environmental Dynamics along the Historical Silk Road. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-00728-7_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-00728-7_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-00727-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-00728-7

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)

Zhongguo Dizhen Ziliao Nianbiao. Chronological Tables of Earthquake Data of China, 1–2.

Zhongguo Dizhen Ziliao Nianbiao. Chronological Tables of Earthquake Data of China, 1–2.

Zhongguo Kexueyuan Dizhen Gongzuo Weiyuanhui Lishizu Bianji. Chinese Academy of Science Working Committee on Earthquake History Editing Team (Ed.). 科学出版社出版 Kexue Chubanshe Chuban. Science Press, Beijing.

Zhongguo Kexueyuan Dizhen Gongzuo Weiyuanhui Lishizu Bianji. Chinese Academy of Science Working Committee on Earthquake History Editing Team (Ed.). 科学出版社出版 Kexue Chubanshe Chuban. Science Press, Beijing. (1960). 中国地震目录 第1集, 科学出版社, 北京.

(1960). 中国地震目录 第1集, 科学出版社, 北京.