Abstract

Background: During the 1990s, a number of new cytotoxic agents with clinically relevant activity in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and with a more favourable therapeutic index than drugs already in use, became available. Given the high prices of these new drugs and the large number of patients affected, it is important to compare the relative benefits and costs of these treatments with the existing regimens before treatment policy decisions are changed.

Purpose: An economic evaluation of three different regimens of chemotherapy in patients with advanced NSCLC was performed from the perspective of the Dutch health insurance system using tariffs valid for 2002. The economic evaluation was integrated into a phase III clinical trial in which the reference regimen cisplatinpaclitaxel was compared with two experimental regimens: cisplatin-gemcitabine and gemcitabine-paclitaxel.

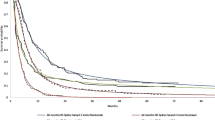

Materials and methods: Unit costs were applied to resource use data collected prospectively on case report forms during the trial. The average total (uncensored) cost per patient was determined for each of the treatment groups. The principal outcome measure for the economic evaluation was the estimated mean survival time per treatment group. This outcome was then incorporated into incremental cost-effectiveness ratios based on costs corrected for censoring. The impact of uncertainty was assessed by bootstrap techniques, and the analysis and interpretation of the data focused on the bivariate density of differences in outcomes and costs in the incremental cost-effectiveness plane. The final results were summarised by the derivation of cost-effectiveness acceptability curves.

Results: The estimated mean survival time was equivalent in the two cisplatinbased regimens with largely overlapping confidence intervals. There was a 99% probability that cisplatin-gemcitabine is the least costly regimen of the two and a 72% probability that this regimen reduces costs while at the same time improving survival. Compared with cisplatin-paclitaxel, the gemcitabine-paclitaxel regimen engendered a borderline significant reduction in mean survival time combined with an almost 90% probability of an increase in costs.

Conclusion: The two cisplatin-based regimens are equivalent in terms of survival, but cisplatin-gemcitabine may reduce costs by approximately €2000 per patient compared with cisplatin-paclitaxel. Gemcitabine-paclitaxel is a dominated option with higher costs and a reduction in mean survival time compared with cisplatinpaclitaxel.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In the SW quadrant, λ should be interpreted as the reduction in costs that the decision maker requires in order to accept a deterioration of survival.

Comparison with the examination of the choice of first treatment modality for second-line therapy, which was quite similar across the treatment groups.

From the three hospitals recruiting most patients to the trial (37% of the total), we have received claims data, i.e. the hospital electronic files recording (in principle) all the resources used and procedures performed for the patients during hospital stays or outpatient consultations. We are preparing an analysis to compare the direct medical costs as determined from the claims data and the costs determined on the basis of the data recorded in the case report forms of the clinical trial.

References

Lees M, Aristides M, Maniadakis N, et al. Economic evaluation of gemcitabine alone and in combination with cisplatin in the treatment of nonsmall cell lung cancer. Pharmacoeconomics 2002; 20: 325–37

Clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of unresectable non-small-cell lung cancer. Adopted on May 16, 1997 by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol 1997; 15: 2996-3018

Smit EF, van Meerbeeck JPAM, Lianes P, et al. A three-arm randomized study of two cisplatin-based regimens and paclitaxel-gemcitabine in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a phase III trial of the EORTC Lung Cancer Group (EORTC 08975). J Clin Oncol 2003; 21: 3909–17

College Tarieven Gezondheidszorg. Tariefboek medisch specialisten and Bijlage bij Tarieflijst Instellingen 2002 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.ctgzorg.nl [Accessed 2003 Sep]

College voor Zorgverzekeringen. Farmakotherapeutisch Kompas 2002. Amstelveen: Medisch Farmaceutische Voorlichting, 2002

van Agthoven M, van Inefeld BM, de Boer MF, et al. The costs of head and neck oncology: primary tumours, recurrent tumours and long-term follow-up. Eur J Cancer 2001; 37: 2204–11

van Agthoven M, Vellenga E, Fibbe WE, et al. Cost analysis and quality of life assessment comparing patients undergoing autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation or autologous bone marrow transplantation for refractory or relapsed non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma or Hodgkin’s disease: a prospective randomized trial. Eur J Cancer 2001; 37: 1781–9

Lau EW, Ng GA. Visual illusions created by survival curves and the need to avoid potential misinterpretation. Med Decis Making 2002; 22: 238–44

Karrison TG. Use of Irwin’s restricted mean as an index for comparing survival in different groups: interpretation and power considerations. Control Clin Trials 1997; 18: 151–67

Neymark N, Adriaenssen I, Gorlia T, et al. Estimating survival gain for economic evaluations with survival time as principal endpoint: a cost-effectiveness analysis of adding early hormo nal therapy to radiotherapy in patients with locally advanced prostate cancer. Health Econ 2002; 11: 233–48

Neymark N, Gorlia T, Adriaenssen I, et al. Cost effectiveness of paclitaxel/cisplatin compared with cyclophosphamide/cisplatin in the treatment of advanced ovarian cancer in Belgium. Pharmacoeconomics 2002; 20: 485–97

Lin D, Feuer EJ, Ettzioni R, et al. Estimating medical costs from incomplete follow-up data. Biometrics 1997; 53: 419–34

Willan AR, Lin DY, Cook RJ, et al. Using inverse-weighting in cost-effectiveness analysis with censored data. Stat Methods Med Res 2002 Dec; 11 (6: 539–51

Briggs AH, Mooney CZ, Wonderling DE. Constructing confidence intervals for cost-effectiveness ratios: an evaluation of parametric and non-parametric techniques using Monte-Carlo simulation. Stat Med 1999; 18: 3245–62

Gold M, Russell L, Siegel J, et al. Cost effectiveness in health and medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996

Oostenbrink JB, Koopmanschap MA, Rutten FFH. Handleiding voor kostenonderzoek. The Netherlands: CVZ Amstelveen, 2000

Dranitsaris G, Cottrell W, Evans WK. Cost-effectiveness of chemotherapy for nonsmall-cell lung cancer. Curr Opin Oncol 2002; 14: 375–83

Ramsey SD, Mainpour CM, Lovato LC, et al. Economic analysis of vinorelbine plus cisplatin versus paclitaxel plus carboplatin for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Nall Cancer Inst 2002; 94: 291–7

Waters JS, O’Brien MER. The case for the introduction of new chemotherapy agents in the treatment of advanced non small cell lung cancer in the wake of the findings of the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE). Br J Cancer 2002; 87: 48–90

Plosker GL, Hurst M. Paclitaxel: a pharmacoeconomic review of its use in non-small cell lung cancer. Pharmacoeconomics 2001; 19: 1111–34

Annemans L, Giaccone G, Vergnenegre A. The cost-effectiveness of paclitaxel + cisplatin is similar to that of teniposide + cisplatin in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a multicountry analysis. Anticancer Drugs 1999; 10: 605–15

Gralla RJ, Grusenmeyer PA, Brooks BJ. Evaluating the costs and cost-effectiveness of new regimens for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [abstract]. 33rd Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol, 1997 May 17; Denver: 420

Schiller D, Harrington D, Chandra P, et al. A randomized phase III trial in metastatic NSCLC: an Eastern Co-operative Group trial (ECOG 1594). N Engl J Med 2000; 346: 92–8

Berger AM, Clark-Snow RA. Adverse effects of treatment: nausea and vomiting. In: de Vita VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, editors. Cancer: principles & practice of oncology. 6th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001

Sanchez LA, Holdsworth M, Bartel SB. Stratified administration of serotonin 5-HT3 receptor antagonists (setrons) for chemotherapy-induced emesis: economic applications. Pharmacoeconomics 2000; 18: 533–56

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Marie-Ange Lentz of the EORTC Data Center for data management, Catherine Legrand of the EORTC Data Center for the statistical analysis of the clinical data, and Dr G. Giaccone in his capacity as chairman for the EORTC Lung Group during the period of the study. We also thank Bristol-Myers-Squibb and Eli Lilly for providing Taxol® (paclitaxel) and Gemzar® (gemcitabine) as investigational agents free of charge.

The authors would like to acknowledge the important contribution to patient accrual of the following investigators: F. Schramel (St. Antonius Ziekenhuis, Nieuwegein, The Netherlands); H. Smit (Rijnstate Hospital, Arnhem, The Netherlands); R. Gaafar (National Cancer Institute, Cairo, Egypt); B. Biesma (Bosch Medicentrum, s’Hertogenbosch, The Netherlands); C. Manegold (Thoraxklinik, Heidelberg, Germany); M. Koolen (Academisch Medisch Centrum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands); F. Wilschut (Ziekenhuis Gelderse Vallei, Bennekom, The Netherlands); J. Stigt (Sophia Ziekenhuis, Zwolle, The Netherlands); A. Van Bochove (Ziekenhuis De Heel, Zaandam, The Netherlands); W. Pieters (Elkerliek Ziekenhuis, Helmond, The Netherlands); N.J.J. Schlosser (Universitair Medisch Centrum, Utrecht, The Netherlands); A. Price (Western General Hospital, Edinburgh, UK); R. Schipper (Catharina Ziekenhuis, Eindhoven, The Netherlands); M-A. Haller (CHRU De Nancy — Hopitaux de Brabois, Nancy, France); A. Lukker (St. Maartens Gasthuis, Venlo, The Netherlands); J. Bozzino (Newcastle General Hospital, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, UK); N. Van Walree (Ziekenhuis De Baronie, Breda, The Netherlands); H. Belderbos (St. Ignatius Ziekenhuis, Breda, The Netherlands); P. Zatloukal (University Hospital Bulovka, Prague, Czech Republic); M. Möllers (Gelre Ziekenhuizen — Lukas locatie, Apeldoorn, The Netherlands), H. Dik (Rijnland Ziekenhuis, Leiderdorp, The Netherlands); V. Spataro (Ospedale San Giovanni, Bellinzona, Switzerland); H.B. Kwa (Onze Lieve Vrouw Gasthuis, Amsterdam, The Netherlands); D. Galdermans (Algemeen Ziekenhuis Middelheim, Antwerpen, Belgium); L. Willems (Leiden University Medical Centre, Leiden, The Netherlands); B. Rapoport (The Medical Oncology Centre of Rosebank, South Africa).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix 1: Assumptions Regarding Antiemetic Regimens

Appendix 1: Assumptions Regarding Antiemetic Regimens

The cisplatin regimens used (80 mg/m2) are highly emetogenic. That is, they are at level 5 of the scale by Berger and Clark-Snow,[24] which indicates the emetogenic potential of chemotherapeutic agents. Both paclitaxel and gemcitabine are level 2, so their combination should be level 3, moderately emetogenic, with emesis induced in 30–60% of the patients. At level 5, >90% of the patients experience emesis. As the case report forms were not intended to record the regimens and the doses of antiemetics used, the cost calculations must proceed based on assumptions.

Based on a review of the literature, and especially the survey by Sanchez et al.,[25] we have assumed the regimens described below. These are partly adapted to the varying emetogenicity of the chemotherapy agents used.

-

Cisplatin-paclitaxel: IV dexamethasone 20mg + IV ondansetron 8mg and then 24 mg/day orally for 3 days.

-

Cisplatin-gemcitabine: IV dexamethasone 20mg + IV ondansetron 8mg and then 24 mg/day orally for 3 days.

-

Gemcitabine-paclitaxel: IV dexamethason 20mg + IV ondansetron 8mg and then 12 mg/day orally for 3 days.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Neymark, N., Lianes, P., Smit, E.F. et al. Economic evaluation of three two-drug chemotherapy regimens in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Pharmacoeconomics 23, 1155–1166 (2005). https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200523110-00007

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200523110-00007