Abstract

Background

Aedes aegypti is a major insect vector because it transmits dreadful viruses as adults that cause disease in humans and other vertebrates. The use of mosquito’s microbiota has shown great potential impacts on vector control and mosquito reproductive competence. The present study aimed to examine the resident bacteria of mosquitoes which are used as a potent range to reduce the A. aegypti fitness. Isolated resident-bacterial strains from blood-fed Aedes species were characterized using gene sequencing and phylogenetic analysis, to assess the inhabitant bacterial strains survival rate in A. aegypti midgut, instar developmental duration, malformation and reproductive competence.

Results

The genetic distinctiveness of isolated bacterial strains belong to the genus Exiguobacterium spp. and further non-redundant nucleotide database search revealed that the species of effective strains were E. aestuarii (MN629357) and E. profundum (MN625885). Exposure of the freshly hatched larvae with these bacteria cell densities extended the developmental duration. For instance, exposure of A. aegypti larva with 0.42 × 108, 0.84 × 108 and 1.68 × 108 cells/mL of E. aestuarii extended the total developmental duration to 11.41, 14.29 and 14.78 days, respectively. It also reduced the fecundity and hatchability of A. aegypti female, with exposure to these bacteria, from 1033.33 eggs/10 females in the control series to 656.67 eggs/10 females.

Conclusions

These present findings indicate that the resident-bacterial strains from blood-fed mosquito not only extend the larval durations but also rendered the A. aegypti females sterile to various extents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Dengue is an emerging infectious disease in the world and is transmitted through the bite of infected Aedes species. It is regarded as the most crucial vector-borne viral disease globally (Bhatt et al., 2013; Murray et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2007). At present, the dengue vectors are controlled through inhabitant microbes proved to be an efficient approach to control the diseases with specific to the target organisms. For instance, insect midgut microbiota involved in many biological processes including nutrition, digestion, reproduction, development and refractoriness to pathogens (Paul et al., 2014; Valzania et al., 2018). Besides, some resident bacteria mainly influence the physiology of mosquito species; especially induce the sterility and extent mosquito development. In contrast, an elevated amount of bacterial load in the food nourishment sped larval growth and their development in Anopheles (Emami et al., 2017). In A. gambiae, larvae treated with Asaia showed faster development as it took less than 2 days to reach the pupal stage (Mitraka et al., 2013) and also larval midgut bacteria play a vital role in their growth and metamorphosis (Coon et al., 2017).

On the other hand, most studies that explore the sexual behavior of clinical important mosquitoes have compared fetal capability in sterilized and wild-type males (Balestrino et al., 2010; Boyer et al., 2011; Madakacherry et al., 2014). Also, sexual behavioral studies have largely excluded female AIDS ethnicity. The measurement of reproductive behavior and mating events is often excluded. Notably, there are only a limited number of studies on mosquito infertility (Devine et al., 2009). For reducing the vector competence of mosquito, the approach of microbial symbionts plays a novel method to control the spread of arthropod-transmitted pathogens (Cirimotich et al., 2011) and various aspects of genetic manipulated Wolbachia and its role in the suppression of mosquito’s population reviewed (Mishra et al., 2018). This genetic technique depends on releasing a high dose of a male mosquito infected by Wolbachia infected with wild-type males to induce sterility and suppress the mosquito competence (Brelsfoard & Dobson, 2011; Kamtchum-Tatuene et al., 2017). With the exception of Wolbachia, the important interactions between mosquitoes and their associated microbiota have not yet been explored. Most of the studies focused on bacterial diversity and their role. Nevertheless, a common conclusion is that more comprehensive analysis of symbiotic mosquito interactions requires at least functional level. Therefore, the present study has been focused an overview of the diversity of resident-bacterial strains from blood-fed Aedes spp. their potential functions in mosquito reproductive biology and future applications in resident-based mosquito control strategies or in order to reduce the mosquito competence.

Methods

Sample collection

Blood-fed mosquitoes were collected around the residential areas of Shenbhagathoppu (Latitude 9°541′ Longitude 77°559′), Srivilliputtur in Tamilnadu. From each sampling station, outdoor resting adult female mosquitoes were collected at dawn and dusk. The collected mosquitoes were anesthetized using chloroform, and primarily Aedes species was morphologically identified using standard taxonomic key (Barraud, 1934). They were surface sterilized with 70% ethanol for 2 min followed by washing twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). From each site, a total of 10 blood-fed Aedes were microscopically dissected out under sterile conditions and transferred individually to 100 µl of brain heart infusion broth (BHI broth) in 1.5 ml centrifuge tubes and enriched for 4 h at room temperature. Then, an equal volume of 40% glycerol solution was added in each tube and stored in − 20 °C for further studies.

Isolation of bacterial strains

Midgut contents of Aedes ten-fold serially diluted up to 10−8 dilution in PBS and 100 µl of each dilution was spread on tryptose soya agar (TSA) supplemented with 5% sheep blood and incubated at 30 °C for 48–72 h. The bacterial isolates were grouped based on their colony morphology. Nevertheless, these isolates were grown separately in TSA medium at 30 °C on an orbital shaker (120 rpm) for 24 h. Bacterial cells were diluted to final volumes of × 108, × 107 and × 106 cells/mL and cell densities determined with a hemocytometer. After dilution with sterile water, 30 mL of a given cell density of an isolate was tested against 3rd instar larvae of A. aegypti and any abnormal behavior and deformities of infected larvae were carefully observed. Further, effective colonies with distinct morphological features were selected and sub-cultured on TSA plates until a pure culture was obtained for further analysis.

DNA extraction and PCR amplification of 16S rRNA

Pure bacterial isolates from mosquito midguts were sub-cultured in 5 ml tryptose soya broth (TSB) at 30 °C for 24 h. Cell pellets were suspended in distilled water and lysed using repeated cycles of freezing and thawing, lysozyme and proteinase-K treatment followed by isopropanol precipitation method (Sambrook et al., 2006). Complete 16S rRNA gene in the extracted genomic DNA carried out in 25 μl of PCR-reaction mixture which contains 2 µl of each primer 27F (5′ AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG 3′) and 1429R (5′ GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT 3′), 12.5 µl of master mix and 6.5 µl of MilliQ water. The PCR amplifications were performed as per the following steps: The initial denaturation of DNA at 94 °C for 5 min, 35 cycles comprising 1 min denaturation at 94 °C, 1 min annealing at 55 °C, 2 min elongation step at 72 °C followed by a final extension step at 72 °C for 7 min. The amplified gene product in 1.2% Agarose gel was visualized under UV transilluminator (Drancourt et al., 2000).

Sequence and phylogenetic analysis

The amplified gene product was purified using the isolation kit method (Qiagen, Düsseldorf, Germany) at Eurofins Pvt. Ltd, Bangalore. The obtained nucleotide sequence was edited and deposited in NCBI. Further, the nucleotide BLAST was performed to study the phylogenetic status. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the similar sequences collected from the NCBI and the tree was constructed using MegaX. The comparison was made using the already available nucleotide gene sequence data in NCBI (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi).

Exiguobacterium survival in A. aegypti midgut

To assess E. aestuarii and E. profundum survival rate in A. aegypti midgut, mosquito larvae were allowed to feed on freshly cultured bacteria with food. The bacteria cultured in the medium as described above and the cell pellet was harvested by centrifugation and mixed with mosquito larval food at different cell densities. A total of 40 mosquitoes were dissected at 2nd and 4th day of post-feeding, and an entire midgut was examined by fluorescence microscopy to detect the resident bacteria like Exiguobacterium and the dissected midguts were observed twice for investigating in the presence of bacteria.

Instar duration and malformation

Freshly hatched I instar larvae of A. aegypti were reared separately in 150 ml of dechlorinated water containing three setup of bacterial densities (cells/mL) of the selected Exiguobacterium spp. Before the exposure of these strains, the culturing method of mosquito was followed as described by Rajagopal and Ilango (2020). The selected cell densities of the bacteria were less than the lethal effect of the respective bacteria for I instar larva. Therefore, the resident bacteria permitted emergence of more than 50% of the ingested larvae. Normal control was also maintained. Three replicates for the control and the different cell densities were maintained. The larvae were provided with dry yeast powder and dog biscuit in the ratio of 3:1. The level of water in the test plastic cups was maintained by adding the required volume of dechlorinated water. After the larvae metamorphosed into pupa, they were transferred to emergence cages and were allowed to emerge. Duration required for the completion of the different instars, number of individuals that suffered malformations, was counted and noted. Growth index (GI) indicates growth regulatory activity of the action of resident bacteria. It was calculated relating to the emergence of Exiguobacterium inhabitant larvae to average developmental period and was expressed in terms of percentage.

Fecundity and hatchability

Fifty freshly hatched larvae of A. aegypti were reared separately in 300 ml of dechlorinated water containing different cell densities of the Exiguobacterium. Triplicates were maintained for control and different cell densities. After the larvae metamorphosed into pupae, they were transferred to emergence cages and were allowed to emerge. Number of males and females that emerged from different cell densities during incubation and control were counted. The ratio between male and female was calculated. The male mosquitoes were provided with 10% sugar solution and females were provided with blood meal from an immobilized rat, kept overnight inside the cage. The cages were covered with wet cloth to maintain constant humidity (85 ± 5%). One small bowl containing water was also kept inside the cage to facilitate oviposition of females. The eggs oviposited by females were removed from the cage next morning. Eggs were counted and allowed to hatch in enamel trays. The number of eggs that successfully hatched into first instar larvae in each concentration was counted. Fecundity was monitored for 25 days and relating fecundity and hatchability of the infected female to those of control female, reduction in fecundity and hatchability due to infection was calculated in percentage. Sterility index (SI) was calculated the formula as described by Saxena et al., (1993)

Statistical analysis

Mean of triplicate data of fecundity and hatchability was calculated using standard statistical formula. The significant differences between the different concentrations were determined by regression analysis by using Origin-Pro 8.5 software package.

Results

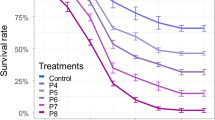

In the present study, bacterial diversity in the midgut from blood-fed mosquito species was analyzed by using pure culture methods. Before, the blood-fed mosquito samples were collected during the post-monsoon from Shenbhagathoppu, Srivilliputtur range, Tamilnadu, where dengue vector population density was quite high. Characterization of gut bacteria in the mosquito collected from all four sites using a culture-dependent method led to the identification of 41 bacterial isolates and also the number of colonies was increased with increase in incubation duration. A total of 162 colonies were counted in all the petri plates in the selected four samples based on their cultural characteristics. Each bacterial isolate was carefully screened against mosquito larvae of A. aegypti. Preliminary study revealed that two bacterial isolates were very closer and inhabitant to the larvae of A. aegypti; hence, further assays were carried out only with these bacterial isolates. The survival rate for these isolates was also analyzed on TSA, water without nutrient media of which results are depicted in Fig. 1 and are further optimized with different pH, temperature. The isolated strains were further identified and characterized, and the size of gene product was approximately 1500 bp. The phylogenetic and genetic distinctiveness indicated that strains belong to genus, Exiguobacterium. The isolates were also identified at the species level by using BLASTn analysis and the species identified as SZM20—E. aestuarii (Gen bank No: MN629357) and SZL6—E. profundum (Gen bank No: MN625885). The 16S rDNA sequence of these bacterial isolates was aligned with reference strains available in GenBank and used for construction of phylogenetic trees as shown in Fig. 2, revealing the relatedness among the bacteria identified. It also revealed that the isolates of SZM20 sequence indicated a 99.57% similarity with E. aestuarii NR 043204.1. The NJ tree revealed a close relationship between the strains isolated in the present study and NR 043204.1 bacterial strain which was also E. profundum. The SZL6 is 99.58% similarity with E. profundum.

Under ambient laboratory conditions, A. aegypti required about 11 and 12 days to complete larval development and pupation and emerge as adult. Exposure of the freshly hatched larvae with different cell densities of selected bacteria extended the developmental duration in resident-bacteria-dependent manner. For instance, exposure of A. aegypti larva with 0.42, 0.84 and 1.68 × 108 cells/mL of E. aestuarii extended the total developmental duration to 11.41, 14.29 and 14.78 days, respectively (Table 1). Likewise, the duration required by this mosquito with 0.5, 1.00 and 2.00 × 108 cells/mL of E. profundum was extended to 12.25, 13.79 and 16.52 days. Number of exposed larvae that emerged as adults was inversely proportional to bacterial densities because high density of chosen bacterial strains induces greater larval extension. The ingested E. aestuarii and E. profundum were labeled with reporter protein to identify the densities of gut microbiota of A. aegypti grown under identical environmental conditions in the laboratory. The results showed that there are communities of similar bacteria in the aquatic habitats of organisms during larval development as shown in Fig. 3. A variety of E. aestuarii and E. profundum were observed in A. aegypti gut on 4th day of post-feeding and the number of bacteria in the midgut was 0.31 × 107 and 0.42 × 107 cfu/midgut, respectively. That is the extent of interference with metamorphosis and adult emergence increased with increase in concentration of the selected bacteria. Consequent to the extension of developmental duration and decrease in the percentage of emergence, growth index of A. aegypti larvae decreased markedly. Growth indices of A. aegypti larvae reared in water free from the bacteria were 7.53, and growth index decreased with increase in cell densities of the selected bacteria.

Observation of ingested bacteria, E. aestuarii and E. profundum labeled reporter protein, GFP (green fluorescent protein) in the gut region of III instar larvae of A. aegypti by fluorescence microscopy. Expression of GFP tagged bacterial strains after the ingestion of 24 and 72 h. a and d Control (unfed mosquito), b and c after 24 and 72 h exposure of E. aestuarii, e and f after 24 and 72 h exposure of E. profundum, respectively

On an average, 10 A. aegypti females in the control series deposited solitary eggs containing 988–1085 eggs each in about 25 days after emergence. Average realized fecundity of a female in the control series is 1033.33 eggs/10 females. The fecundity of A. aegypti female exposed with 0.42 and 1.68 × 108 cells/mL of E. aestuarii decreased from 1033.33 eggs/10 females in the control series to 923.33 and 656.67 eggs/10 females (Table 2), whereas the decrease in the hatchability of the female exposed with 0.50 and 2.00 × 108 cells/mL of E. profundum compared with that of control was 89.35% and decreased to 84.83 and 59.67%. Figure 4 shows the relationship between treatment dose and average fecundity of A. aegypti exposed with E. aestuarii. The inverse relationship between the two variables is statistically highly significant (r = −0.963; N = 15; P < 0.01). Similar significant inverse relationship was also obtained between fecundity and different cell densities of the females exposed with E. profundum. Like fecundity, hatchability of eggs deposited by the females infected with the E. aestuarii and E. profundum also displayed significant inverse relationship with different cell densities. Exposure with E. aestuarii and E. profundum decreased the hatchability to 24.89 and 30.97%, respectively; these decreases were 75.11 and 69.03% less than the hatchability in the respective control series. Consequent to the significant decrease in fecundity of the females exposed with these bacterial strains and decrease in the hatchability of the eggs deposited by them, the strains rendered the A. aegypti females sterile to various extents. Sterility index of A. aegypti linearly increased with different cell densities of resident bacteria. At the highest concentration (2.00 × 108 cells/mL) of E. profundum, sterility index of A. aegypti was 47.37 (Tables 2). Briefly, the results obtained indicate that the selected bacterial strains not only extend the larval durations but also reduce the fecundity and hatchability of A. aegypti and rendered the few which managed to emerge successfully, sterile to a greater extent.

Discussion

In general, microbial diversity in the gut environment is strongly influenced by larval physiology and mosquito behavior. Furthermore, some researchers evidenced the impact of inhabitant bacterial species on their growth and survival of mosquitoes, and the vectors exhibit a different response to bacterial strains and cell densities of the microbes present in water (Souza et al., 2019; Trexler et al., 2003). In this study, selected strains showed persistence in dechlorinated water for up to 120 h. Therefore, we decided to perform larval duration assays by directly inoculating the development of strains in water under sterile conditions. In the present study, it surprisingly observed the extension of larval duration and the induction of morphogenetic defects of larvae inoculated with bacterial cell densities. In this result, E. aestuarii and E. profundum significantly extended the larval durations of A. aegypti at bacterial cell densities of × 107 and × 108 cells/mL.

The present findings agree with the investigations on A. aegypti mosquito using bacterial species isolated from canebrake bamboo (Ponnusamy et al., 2015). Extension of developmental duration, interference with growth and induction of morphogenetic deformities at various stages of development are caused by selected bacterial strains (Rajagopal et al., 2020). Based on this information, the present study could theoretically conclude that infection with resident strains E. aestuarii and E. profundum cause physiological imbalance in the larvae. Furthermore, the selected strains belong to the genus of Exiguobacterium and are non-spore-forming, facultatively anaerobic, gram-positive bacilli and hardly associated with wound infections. Exiguobacterium spp. are widely distributed and they were isolated from different sources, such as water, the environment of food processing plants and rhizosphere of plants (Vishnivetskaya et al., 2009). The clinical characterizations of Exiguobacterium species previously identified from different infectious samples by several workers (Cheng et al., 2013; Kenny et al., 2006; Keynan et al., 2007; Tena et al., 2014). Therefore, the strains may be transmitted from man to mosquitoes through feeding mechanism because the dengue vectors feed on man, which maintain their pathogens within an efficient manner as a mosquito to human transmission cycle (Lambrechts & Failloux, 2012) while undertaken studies on mosquito, Aedes in dechlorinated water, strains have been thoroughly studied under controlled conditions.

E. aestuarii and E. profundum were cell density-dependent negative effect on fecundity of females that emerged from larvae inoculated with the bacteria; in addition to hatchability of these fewer eggs deposited was also very low (Table 2). These findings and observations of present study are supported by few workers. Incompatible insect technique depends on releasing large numbers of Wolbachia-infected male mosquitoes that compete with wild-type males to induce sterility and suppress the mosquito population (Brelsfoard & Dobson, 2011; Zhang et al., 2015). Some optimized bacterial strains that represent the large-scale releases are problematic due to the need for mosquito sex separation at the pupal stage (Zhang et al., 2015). The second assay of our study focused on dengue vector reproductive fitness through assessment of sterility indices. In this study, decrease in fecundity and hatchability of A. aegypti associated with selected bacteria at respective cell densities has been compared with the data reported for different bacteria. For instance, Wolbachia are endosymbiotic bacteria that naturally infect approximately 40% of insect species (Zug & Hammerstein, 2012) and induce a reproductive phenotype in mosquitoes.

Aedes polynesiensis infected with Wolbachia possess bi-directionally and incompatible compared to the naturally infected wild type of mosquitoes was irradiated during the pupal stage and resultant as decreased in fecundity and hatchability of females (Brelsfoard et al., 2009). In contrast, the radiation dose could not affect any negative impact on the fitness of male mosquito, mating competitiveness or to induce CI. For Aedes albopictus, Wolbachia is a milder infection, a double infection and uninfected female A. albopictus. Numerous research has been conducted to establish the minimum pupal irradiation dose need to induce complete infertility in Wolbachia (Zhang et al., 2015). Irradiated A. albopictus, all female strains have decreased fecundity and fertility during irradiated which is inversely proportional to dose. Besides, three A. albopictus strains of the same genetic background (triple-infected, double-infected and uninfected) revealed that the presence of Wolbachia had little effects on host fitness (Zhang et al., 2015). In addition, irradiation dose of female does not have a negative impact on their longevity while the shorter life spans were observed in wild-type males which were irradiated by higher dose (Zhang et al., 2016).

These studies have shown that irradiation was mainly used to diminish the risk of unintentional release of Wolbachia triple-infected female strain during the male release for A. aegypti population inhibition. Recently, stable Wolbachia-infected strain in A. aegypti has been successfully produced by means of embryo microinjection technique (Joubert et al., 2016). In view of the fact that resident bacteria are likely to impact on mosquito host suitability and impact on vector competence, yet research efforts to gain insight into the dynamics and diversity of Aedes-associated bacteria have been limited so far. Therefore, our results further suggested that the direct method of resident bacteria from blood-fed Aedes is more comfortable to infect A. aegypti under controlled conditions. Consequent to the negative effects of A. aegypti associated with bacteria strains on fecundity and hatchability, fertility of the female is very much affected. The bacteria rendered the mosquitoes sterile to various extents.

Conclusions

The resident bacteria tested in the present study against A. aegypti not only inflicted significant larval duration at low cell densities, but also inhabited a greater percentage of the inoculated larvae from emerging as adults, extended their developmental period, induced malformation and rendered their sterile to a greater extent. Resident bacteria are likely to trigger the host suitability and/or fitness, affect the biological hostility and also on vector competence. Thus, our study provides the basis for understanding the resident bacteria from blood-fed Aedes on female fecundity which emerged from larvae infected with these bacteria.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered saline

- TSA:

-

Tryptose soya agar

- TSB:

-

Tryptose soya broth

- GI:

-

Growth index

- SI:

-

Sterility index

- CI:

-

Cytoplasmic incompatibility

- GFP:

-

Green fluorescent protein

References

Balestrino, F., Medici, A., Candini, G., Carrieri, M., Maccagnani, B., Calvitti, M., Maini, S., & Bellini, R. (2010). γ ray dosimetry and mating capacity studies in the laboratory on Aedes albopictus males. Journal of Medical Entomology, 47, 581–591.

Barraud, P. J. (1934). The fauna of British India including Ceylon and Burma. Diptera. Volume V. Family Culicidae. Tribes Megarhinini and Culicini in Salinas, Puerto Rico. Journal of Medical Entomology, 43, 484–492.

Bhatt, S., Gething, P. W., Brady, O. J., Messina, J. P., Farlow, A. W., Moyes, C. L., Drake, J. M., Brownstein, J. S., Hoen, A. G., & Sankoh, O. (2013). The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature, 496, 504–507.

Boyer, S., Gilles, J., Merancienne, D., Lempérière, G., & Fontenille, D. (2011). Sexual performance of male mosquito Aedes albopictus. Medical and Veterinary Entomology, 25, 454–459.

Brelsfoard, C. L., & Dobson, S. L. (2011). Wolbachia effects on host fitness and the influence of male aging on cytoplasmic incompatibility in Aedes polynesiensis (Diptera: Culicidae). Journal of Medical Entomology, 48, 1008–1015.

Brelsfoard, C. L., St Clair, W., & Dobson, S. L. (2009). Integration of irradiation with cytoplasmic incompatibility to facilitate a lymphatic filariasis vector elimination approach. Parasites & Vectors, 2, 38.

Cheng, A., Liu, C.Y., Tsai, H.Y., Hsu, M.S., Yang, C.J., Huang, Y.T., Liao, C.H., & Hsueh, P.R. (2013). Bacteremia caused by Pantoea agglomerans at a medical center in Taiwan, 2000–2010. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology, and Infection, 46, 187–194.

Cirimotich, C. M., Ramirez, J. L., & Dimopoulos, G. (2011). Native microbiota shape insect vector competence for human pathogens. Cell Host & Microbe, 10, 307–310.

Coon, K. L., Valzania, L., McKinney, D. A., Vogel, K. J., Brown, M. R., & Strand, M. R. (2017). Bacteria-mediated hypoxia functions as a signal for mosquito development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114, E5362–E5369.

Devine, G. J., Perea, E. Z., Killeen, G. F., Stancil, J. D., Clark, S. J., & Morrison, A. C. (2009). Using adult mosquitoes to transfer insecticides to Aedes aegypti larval habitats. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106, 11530–11534.

Drancourt, M., Bollet, C., Carlioz, A., Martelin, R., Gayral, J.-P., & Raoult, D. (2000). 16S ribosomal DNA sequence analysis of a large collection of environmental and clinical unidentifiable bacterial isolates. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 38, 3623–3630.

Emami, S. N., Lindberg, B. G., Hua, S., Hill, S. R., Mozuraitis, R., Lehmann, P., Birgersson, G., Borg-Karlson, A.-K., Ignell, R., & Faye, I. (2017). A key malaria metabolite modulates vector blood seeking, feeding, and susceptibility to infection. Science, 355(6329), 1076–1080.

Joubert, D. A., Walker, T., Carrington, L. B., De Bruyne, J. T., Kien, D. H. T., Hoang, N. L. T., Chau, N. V. V., Iturbe-Ormaetxe, I., Simmons, C. P., & O’Neill, S. L. (2016). Establishment of a Wolbachia superinfection in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes as a potential approach for future resistance management. PLOS Pathogens, 12, 66.

Kamtchum-Tatuene, J., Makepeace, B. L., Benjamin, L., Baylis, M., & Solomon, T. (2017). The potential role of Wolbachia in controlling the transmission of emerging human arboviral infections. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases, 30, 108.

Kenny, F., Xu, J., Millar, B. C., McClurg, R. B., & Moore, J. E. (2006). Potential misidentification of a new Exiguobacterium sp. as Oerskovia xanthineolytica isolated from blood culture. British Journal of Biomedical Science, 63, 86–89.

Keynan, Y., Weber, G., & Sprecher, H. (2007). Molecular identification of Exiguobacterium acetylicum as the aetiological agent of bacteraemia. Journal of Medical Microbiology, 56, 563–564.

Lambrechts, L., & Failloux, A. B. (2012). Vector biology prospects in dengue research. Memórias Do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, 107(8), 1080–1082.

Madakacherry, O., Lees, R. S., & Gilles, J. R. L. (2014). Aedes albopictus (Skuse) males in laboratory and semi-field cages: Release ratios and mating competitiveness. Acta Tropica, 132, S124–S129.

Mishra, N., Shrivastava, N. K., Nayak, A., & Singh, H. (2018). Wolbachia: A prospective solution to mosquito borne diseases. International Journal of Mosquito Research, 5(2), 1–8.

Mitraka, E., Stathopoulos, S., Siden-Kiamos, I., Christophides, G. K., & Louis, C. (2013). Asaia accelerates larval development of Anopheles gambiae. Pathogens and Global Health, 107, 305–311.

Murray, N. E. A., Quam, M. B., & Wilder-Smith, A. (2013). Epidemiology of dengue: Past, present and future prospects. Clinical Epidemiology, 5, 299.

Paul, A. M., Shi, Y., Acharya, D., Douglas, J. R., Cooley, A., Anderson, J. F., Huang, F., & Bai, F. (2014). Delivery of antiviral small interfering RNA with gold nanoparticles inhibits dengue virus infection in vitro. Journal of General Virology, 95, 1712.

Ponnusamy, L., Schal, C., Wesson, D. M., Arellano, C., & Apperson, C. S. (2015). Oviposition responses of Aedes mosquitoes to bacterial isolates from attractive bamboo infusions. Parasites & Vectors, 8, 486.

Rajagopal, G., & Ilango, S. (2020). Native Bacillus strains from infected insects : A potent bacterial agent for controlling mosquito vectors Aedes aegypti and Culex quinquefasciatus. International Journal of Mosquito Research, 7(2), 51–56.

Rajagopal, G., Jeyavani, J., & Ilango, S. (2020). Larvicidal and histopathological efficacy of inhabitant pathogenic bacterial strains to reduce the dengue vector competence. Pest Management Science, 76(11), 3587–3595.

Sambrook, J., Russell, D. W., Sambrook, J. (2006). The condensed protocols from molecular cloning: A laboratory manual (No. Sirsi) i9780879697723).

Saxena, R. C., Harshan, V., Saxena, A., Sukumaran, P., Sharma, M. C., & Kumar, M. L. (1993). Larvicidal and chemosterilant activity of Annona squamosa alkaloids against Anopheles stephensi. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association, 9(1), 84–7.

Souza, R., Virginio, F., Suesdek, L., Barufi, J. B., & Genta, F. A. (2019). Microorganism-based larval diets affect mosquito development, size and nutritional reserves in the yellow fever mosquito Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae). Frontiers in Physiology, 10, 152.

Tena, D., Martínez, N. M., Casanova, J., García, J. L., Román, E., Medina, M. J., & Sáez-Nieto, J. A. (2014). Possible Exiguobacterium sibiricum skin infection in human. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 20, 2178.

Trexler, J. D., Apperson, C. S., Zurek, L., Gemeno, C., Schal, C., Kaufman, M., Walker, E., Watson, D. W., & Wallace, L. (2003). Role of bacteria in mediating the oviposition responses of Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae). Journal of Medical Entomology, 40, 841–848.

Valzania, L., Coon, K. L., Vogel, K. J., Brown, M. R., & Strand, M. R. (2018). Hypoxia-induced transcription factor signaling is essential for larval growth of the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115, 457–465.

Vishnivetskaya, T. A., Kathariou, S., & Tiedje, J. M. (2009). The Exiguobacterium genus: Biodiversity and biogeography. Extremophiles, 13, 541–555.

Wu, P.-C., Guo, H.-R., Lung, S.-C., Lin, C.-Y., & Su, H.-J. (2007). Weather as an effective predictor for occurrence of dengue fever in Taiwan. Acta Tropica, 103, 50–57.

Zhang, D., Lees, R. S., Xi, Z., Bourtzis, K., & Gilles, J. R. L. (2016). Combining the sterile insect technique with the incompatible insect technique: III-robust mating competitiveness of irradiated triple Wolbachia-infected Aedes albopictus males under semi-field conditions. PLoS ONE, 11(3), e0151864.

Zhang, D., Zheng, X., Xi, Z., Bourtzis, K., & Gilles, J. R. L. (2015). Combining the sterile insect technique with the incompatible insect technique: I-impact of Wolbachia infection on the fitness of triple-and double-infected strains of Aedes albopictus. PLoS One, 10(4), e0121126.

Zug, R., & Hammerstein, P. (2012). Still a host of hosts for Wolbachia: analysis of recent data suggests that 40% of terrestrial arthropod species are infected. PLoS ONE, 7(6), 38–544.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the management and principal of the Ayya Nadar Janaki Ammal College, Sivakasi, for providing chemical and laboratory facilities.

Funding

No funding was availed from any funding sources.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GR contributed to the study, analysis, interpretation of data, drafted and revised the manuscript. SI contributed to the design, conception of the study and revised the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was carried out in strict accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals 8th Edition 2011.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rajagopal, G., Ilango, S. Exposure of Exiguobacterium spp. to dengue vector, Aedes aegypti reduces growth and reproductive fitness. JoBAZ 82, 47 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41936-021-00246-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41936-021-00246-7