Abstract

Background

Current guidelines on the management of cancer pain include information referred to integral patient management, in order to get an improvement in their quality of care. The assessment of compliance with the recommendations in daily practice constitutes a necessary feedback mechanism for consolidating theoretical recommendations. The objective of the study was to evaluate the fulfilment of quality of care recommendations for patients with cancer pain in real clinical practice.

Methods

A retrospective observational study was designed. A total of 107 centres (81 pain units and 26 palliative care units) collected pooled information on 1605 patients.

The study coordinating committee selected 12 structure and 13 process quality indicators based on the recommendations of different clinical practice guidelines. The process indicators were evaluated through the information obtained from 15 consecutively and retrospectively selected case histories. For each indicator, the participating physicians specified compliance or non-compliance, or whether the indicator measurement was not applicable to the reviewed patient. The degree of compliance with the recommendations on the management of patients with cancer pain was evaluated using the Achievable Benchmarks of Care (ABC)© (University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL, USA).

Results

Mean compliance with all the indicators was 82.4% (95% CI 70.4–94.4). The ABC of the 13 process indicators selected for the study was 100%. No relevant differences were observed in the degree of compliance with the quality indicators between pain and palliative care units, or between geographical areas.

Conclusions

The selected recommendations are applicable to clinical practice and could be used to continuous evaluation of quality of care in patients with cancer. Compliance with the quality indicators in the participating units was very satisfactory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pain has a prevalence of up to 59% among patients subjected to anticancer treatment, and 64% in patients with metastases or advanced or end-stage disease, and is caused through different physiopathological mechanisms [1,2,3].

Despite the high frequency of cancer pain, in clinical practice it has been observed that between 56 and 82.3% of all patients receive less treatment than expected, depending on the type of study and the healthcare setting involved [4,5,6,7,8].

Although there are many guidelines and educational programmes on the evaluation and treatment of cancer pain, its management and control remain deficient [7,8,9]. Also, in addition to adequate pain control, other aspects of patient management must be satisfied in order to ensure appropriate quality of care [10].

Clinical practice guidelines are reference documents created by groups of experts that offer recommendations based on clinical evidence. These documents are of help to clinicians and are currently essential, since they offer a consensus-based summary of the most appropriate approach for dealing with certain situations that can be seen in daily practice. The current guidelines on the management of cancer pain include information referred to integral patient management, in order to get an improvement of their quality care [11].

Once a clinical practice guide has been developed, the next step is to ensure its diffusion and measure its usefulness in the real-life clinical setting. The information obtained from the assessment of compliance with the recommendations in daily practice moreover constitutes a necessary feedback mechanism for consolidating the impact of the theoretical recommendations, and consequently should be incorporated to the guidelines to add practical value.

A number of techniques can be used to assess compliance with the recommendations in clinical practice. The Achievable Benchmarks of Care (ABC)© technique was chosen for the present study. This tool facilitates the assessment, comparison, and dissemination of benchmarks (reference points) drawn from clinical reality and taking the best centres as reference [12].

The objective of the study was to evaluate the quality of care obtained by pain and palliative care units in patients with cancer pain, based on indicators selected from the review of the different guidelines.

Methods

Study design and ethical standards

A retrospective observational study was designed. The Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Consorcio Hospitalario Provincial de Castellón (Spain) approved the study on 1 June 2016. As the information collected in the study were pooled data, it was not applicable to obtain individual informed consent from patients for whom the clinical histories were reviewed.

The study was carried out in accordance with the Good Epidemiology Practice guidelines of the International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology. Likewise, the study was conducted according to the basic ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, where applicable.

Study endpoints

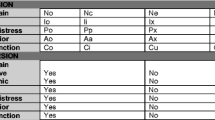

The coordinating committee of the study selected 25 indicators (Table 1): 5 descriptors of the structure of the service and population attending the units; 7 structural indicators; and 13 process indicators, following a review of the recommendations of different clinical practice guidelines [9, 13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. The indicators were selected mainly from the recommendations of the Spanish Society of Palliative Care 2006 [13].

The process indicators were evaluated through the collection of information from 15 consecutively and retrospectively selected case histories (up until 31 March 2016). Data collection was carried out retrospectively in order to avoid information bias. For each indicator, the participating physicians specified compliance or non-compliance, or whether the indicator measurement was not applicable to the reviewed patient (not applicable). The participating physicians received a form to facilitate the collection of information from the case histories. The data were pooled and entered in an electronic database designed for the study, with access limited to the participating physicians.

Calculation of sample size

The sample of 107 pain and palliative care units had a statistical power of 93% in assessing compliance with the process indicators selected for the study, with a precision of ± 6% in the confidence interval of percentage compliance with each indicator and a two-tailed alpha error of 0.05.

Statistical analysis

The indicators were subjected to a descriptive analysis, calculating the percentage of participating units that complied with the structural indicators, and the mean percentage compliance of the process indicators. The results were analysed according to type of unit and geographical zone.

The Student’s t test was used to compare the mean percentages of each indicator according to the type of participating unit. The factor analysis of variance model was used, applying Bonferroni or Games Howell corrections according to the homogeneity of the variances, for controlling multiple comparisons error in contrasting mean compliance of the indicators by geographical zones. The statistical significance level was defined as 0.05. The SPSS version 24.0 statistical package was used for the analysis.

Calculation of the ABC© was made following the methodology of the University of Alabama (Birmingham, AL, USA) [12]. The ABC© model is based on calculation of the paired mean for the 10% of the investigators that comply most with the recommendation. Percentage compliance of each investigator for calculating ABC© was determined using a Bayesian estimator designed by the University of Alabama.

Results

A total of 107 centres participated: 81 pain units (75.7%) and 26 palliative care units (24.3%). The centres were located in 40 Spanish provinces (out of a total of 52) and in 15 autonomous communities (out of a total of 19). The data referred to the process indicators were collected from 15 patients in each centre, totalling 1605 case histories of patients with cancer pain.

On average, the centres participating in the study served a population of 301,094 patients (95% CI 259,083–343,105), with a median of 250,000 patients per centre.

In 1 month, the mean population attended by the centres totalled 216 patients (95% CI 184–294), with a median of 200 patients. There were statistically significant differences (p < 0.0001) in the number of patients attended in the pain units, totalling 254 patients a month (95% CI 215–293), versus the palliative care units, totalling an average of 98 patients a month (95% CI 73–122).

On average, 27% of the patients attended in the clinic were cancer patients with poor pain control (95% CI 21–32), with a median of 15%. There were statistically significant differences in the mean proportion of cancer patients with poor pain control - the percentage being significantly higher in the Palliative Care Units (p < 0.0001), with a mean difference of 53% (95% CI 44–62).

Figure 1 shows the structure indicators results according to the care unit involved. There were statistically significant differences (p = 0.010) in structural indicator S1 between the pain units (33.3%) and the palliative care units (7.7%), as well as in indicator S3 (p = 0.002) between the pain units (86.4% of the units) and the palliative care units (57.7%).

Compliance of structure indicators* according to type of unit. *See indicator code in Table 1

The proportion of patients in which the investigators considered the indicator not applicable provided information on the capacity of the indicator to be used on a generalised basis, and required commenting for improvement when the proportion was higher than 10% of the cases.

Table 2 shows the analysis of applicability of the indicators selected for the study.

No significant differences were observed between the percentage applicability of the indicators between the two types of units participating in the study. The applicability of the selected indicators was considered to be adequate.

Figure 2 describes the mean proportion of patients in which each process indicator was found to be compliant, with the corresponding ABC©, according to the type of participating unit and for the global patient sample. There were statistically significant differences in mean percentage compliance of indicators 12 and 13 between the patients followed-up on in the pain units and in the palliative care units. In the case of indicator 12, the mean difference between the two types of units was 38% (95% CI 18–58) (p = 0.001). In the case of indicator 13, the mean difference between the two types of units was 34% (95% CI 16–53) (p < 0.0001).

Compliance of process indicators* according to type of unit: Achievable Benchmarks of Care were 100% for all indicators. *See indicator code in Table 1

Mean percentage compliance of the 13 process indicators was 82.4% (95% CI 70.4–94.4) in all the centres, versus 81.5% (95% CI 67.6–95.4) in the pain units and 85.1% (95% CI 77.3–92.9) in the palliative care units.

No differences in indicator compliance were observed among the different autonomous communities.

There were no particular characteristics in the centres with the best indicator compliances capable of distinguishing them from the rest of the centres and which might be recommended.

Discussion

Assessment of compliance with the recommendations of the clinical practice guidelines, which seek to improve the quality of patient care, can be used to determine whether corrective measures are needed, whether further unit staff training is required, or whether new tools should be adopted to help comply with the recommendations [21]. Periodic assessment of the degree of compliance can also be used to determine whether the quality of the department is improving or not, or whether it remains within acceptable limits.

In certain cases, compliance with the recommendations is not possible; this happens when information is transferred from a theoretical setting to clinical practice. Therefore, once the quality indicators have been determined, the degree to which they can be complied with in the real-life setting should be assessed, establishing comparisons with other centres, if possible. In this way, we can determine what elements distinguish those units exhibiting better compliance with the recommendations, with a view to then applying them to our own unit, if possible.

Different documents describe indicators that assess the objective of quality care in patients with cancer pain, and although they share the common aim of improving patient care, they are targeted to different groups of professionals, pain units, palliative care units, or pain treatment units considered globally, and involve different quality measures referred to patient care that might not be applicable to all healthcare settings [9, 13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21].

With the purpose of securing a manageable number of indicators allowing periodic assessment, we selected 25 structure and process indicators that could be measured in pain units and palliative care units (Table 1).

The main objective of this study was to evaluate the quality of care in patients with cancer pain, assessing the degree of compliance with the recommendations for pain management and quantifying it by means of the ABC© technique [12].

The structure indicators are referred to the availability of materials, protocols, or interventions related to the care of patients with cancer pain. Most centres (72.9%)(Fig. 1, S1) did not have perceived quality of care questionnaires to be completed by the attended patients. Although 68.2% of the centres had care protocols based on the recommendations for the management of cancer pain, and 79.4% had patient information documents on pain and the procedures available for its treatment (Fig. 1, S2 and S3), this is a quality control area for improvement—especially in the palliative care units, which showed lesser compliance with the indicator (p = 0.002). Only 47.7% of the centres had protocols for patient follow-up and referral from the Departments of Oncology, Radio Therapeutic Oncology, and Palliative Care to the Pain Unit (Fig. 1, S4). Designing a patient follow-up circuit is clearly needed in order to improve the quality of care in an integral manner, and this referral protocol should be reflected in writing in order to facilitate patient follow-up [22, 23]. The proportion of centres in which monographic multidisciplinary consultations were made on relevant chronic painful disorders was found to be low (61.7%, Fig. 1, S5). A minimum number of meetings should be established in each centre as a necessary means for establishing consensus with other specialists on how to deal with the patient in special situations. Indicator S6 (Fig. 1) was included in the study to determine whether the International Classification of Diseases—Ninth Edition (ICD-9) coding system for acute or chronic pain in cancer patients was being adequately applied or not. Only 37.4% of the centres assigned code 338.3, to this group of patients, i.e., two-thirds of the patients were not correctly coded, and consequently, the recorded prevalence was lower than the true prevalence. As a result of such incorrect coding, the economic justification of the treatments assigned to this patient population does not reflect the real situation, and budget planning is therefore insufficient. The pain units applied such coding to a lesser extent than the palliative care units (p < 0.01).

The availability of registries of patients attended in the unit facilitates adequate control and follow-up, and also makes it possible to conduct epidemiological and quality control studies. We found that 95.3% of the centres had patient registries.

Compliance with the process indicators selected for the study was evaluated by reviewing 15 case histories of patients with cancer pain per unit, representing information on a total of 1605 patients. Data collection had to be carried out retrospectively in order to minimise information bias. We first determined whether the chosen indicators were applicable to the patients selected for the study. It was seen that on average, the 13 selected indicators were not applicable in 4.7% of the reviewed patients, and none of the indicators exceeded the proportion of 10% established as the statistical limit (Table 2). Therefore, these are questions that can be applied to most patients with cancer pain treated in our clinics.

Mean percentage compliance of the 13 process indicators was 82.4% (95% CI 70.4–94.4) in all the centres. We consider this proportion to be very adequate, though still amenable to improvement, since the ABC© of all the indicators was seen to be 100%. In other words, in the 10% of centres where these indicators show the highest compliance rates (i.e., reference or benchmark centres), all the indicators are fulfilled in 100% of the patients with cancer pain.

Figure 2 shows the percentage compliance for each process indicator in all the centres and according to type of unit. We consider compliance referred to indicators P1 to P9 to be adequate. However, indicators P10 to P13 showed areas for improvement. Indicator P10 evaluated whether adherence to therapy was reflected in the case history, and was found to be measured in 73.9% of the patients. Adherence to therapy is essential in order to reach the clinical objectives. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), an increase in intervention effectiveness designed to improve adherence could have a greater impact upon the health of the population than any other improvement referred to a specific treatment. For this reason, it is very important to have measures for assessing adherence and to reflect them in the case histories [24].

Indicator P12 collected information on the proportion of patients subjected to psychological evaluation—this being done in only 31% of the cases. Furthermore, we found the proportion in the pain units to be significantly lower (21.8%) than in the palliative care units (59.7%; p = 0.001). The reason for this may be that the patients reach these units with a previous psychological evaluation, since they come from the Department of Oncology, where most centres include an oncological psychologist among the staff.

Lastly, indicator P13 explored whether the patients had undergone an initial evaluation of their needs, with due reflection in the case history. This was seen to be the case in 43.1% of the patients, with significant differences between the two types of units (p < 0.0001). In the palliative care units, it was more frequent to find medical and nursing questionnaires to evaluate these needs.

The results obtained constitute a starting point for improving the quality of care in our patients. In this study, coordinating team consensus-based selection of the 25 indicators might not be complete, with the obviation of other equally quantifiable areas of interest. Data collection from the case histories might not reflect all the data, due to a number of factors such as different interpretations of each question; failure to enter all the obtained information in the case history; or failure to find information that has indeed been entered in the case history. In order to avoid such situations in the future, the indicators should be clearly defined, with the availability of checklists in the case histories to confirm adequate compliance.

The centres participating in the study received information on percentage compliance of the indicators and were able to establish comparisons with the overall average and with their type of unit. In addition to quantifying current quality and being able to identify areas for improvement, each centre could use this information as a reference point for quality control in future evaluations. The present study therefore will have practical repercussions.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the indicators selected for the study are applicable to clinical practice, can be fulfilled (ABC© 100%), and allow quality control based on a quantitative measure. It is advisable to introduce checklists to confirm compliance with the quality indicators in units that attend patients with cancer pain, since they contribute to quantify the quality of patient care.

Abbreviations

- ABC:

-

Achievable Benchmarks of Care

- ICD-9:

-

International Classification of Diseases-Ninth Edition

References

Van den Beuken-van Everdingen MHJ, De Rijke JM, Kessels AG, et al. Prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: a systematic review of the past 40 years. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1437–49.

Teunissen SC, Wesker W, Kruitwagen C, et al. Symptom prevalence in patients with incurable cancer: a sysematic review. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2007;34:94–104.

Sun V, Borneman T, Piper B, Koczywas M, Ferrell B. Barriers to pain assessment and management in cancer survivorship. J Cancer Surviv. 2008;2:65–71.

Deandrea S, Montanari M, Moja L, Apolone G. Prevalence of undertreatment in cancer pain. A review of published literature. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(12):1985–91.

Costantini M, Ripamonti C, Beccaro M, et al. Prevalence, distress, management and relief of pain during the last three months of cancer patients’ life. Results of an Italian mortality follow-back survey. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:729–35.

Breivik H, Cherny N, Collett F, et al. Cancer-related pain: a pan European survey of prevalence, treatment, and patient attitudes. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1420–33.

Higginson IJ, Murtagh F. Cancer pain epidemiology. In: Bruera E, Portenoy RK, editors. Cancer pain Assessment and Management, vol. 3. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2010. p. 37–52.

Morselli M, Bandieri E, Zanin R, et al. Pain and emotional distress in leukaemia patients at diagnosis. Leuk Res. 2009;34(2):e67–8.

Unidad de tratamiento del dolor. Estándares y recomendaciones de calidad y seguridad. Ministerio de Sanidad política social e igualdad. Spain: Informes, estudios e investigación; 2011.

Abernethy AP, Hanson LC, Main DS, Kutner JS. Palliative care clinical research networks, a requirement for evidence-based palliative care: time to coordinated action. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:845–50.

Ouwens M, Hulscher M, Hermens R, et al. Implementation of integrated care for patients with cancer: a systematic review of interventions and effects. Int J for QUality in Health Care. 2009;21(2):137–44.

Kiefe CI, Weissman NW, Allison JJ, et al. Methodology matters-XII. Identifying achievable benchmarks of care: concepts and methodology. Int J Qual Health Care. 1998;10(5):443–7.

Indicadores y estándares de calidad en cuidados paliativos. Sociedad Española de Cuidados Paliativos. Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo. Spain: Fundación Avedis Donabedian; 2006.

Guía de Práctica Clínica sobre cuidados paliativos. Guías de práctica clínica en el SNS. Spain: Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo; 2008.

Radbruch L, Payne S, Bercovitch M, Caraceni A, et Al. White Paper on standards and norms for hospice and palliative care in Europe. Recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care: part 2. Eur J Palliat Care. 2010;17(1):22-33.

Programas de seguridad del paciente en las unidades de tratamiento del dolor. Informes de evaluación de tecnologías Sanitarias. Spain: AETSA; 2009.

Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo. Estrategia en cuidados paliativos del sistema nacional de salud. Spain, 2007. Available in: http://www.mspsi.gob.es/organizacion/sns/planCalidadSNS/docs/paliativos/cuidadospaliativos.pdf.

Palanca Sánchez I, Puig Riera de Conías MM, Elola Somoza J, Bernal Sobrino JL, Paniagua Caparrós JL, Grupo de Expertos. Unidad de tratamiento de dolor: estándares y recomendaciones. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad, Política Social e Igualdad; 2011.

De la Calle JL, Abejón D, Cid J, del Pozo C, Insausti J, López E y el Panel de expertos de la Sociedad Madrileña del Dolor. Estándares de calidad asistencial y catálogo de procedimientos de las unidades de dolor crónico. Rev Soc Esp Dolor. 2010;17:114–33.

Ripamonti CI, Santini D, Maranzano E, Berti M, Roila F, on behalf of the ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Management of cancer pain: ESMO Clinical Practice GUidelines. Annals Oncoology. 2012;23(Suppl 7):vii139-54.

Kamal AH, Gradison M, Maguire JM, Taylor D, Abernethy AP. Quality measures for palliative care in patients with cancer: a systematic review. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(4):281–7.

Ouwens M, Wolersheim H, Hermens R, Hulscher M, Grol R. Integrated care programmes for chronically ill patients: a review of systematic reviews. Int J for Quality in Health Care. 2005;17(2):141–6.

Mainz J. Defining and classifying clinical indicators for quality improvement. Int J for Quality in Health Care. 2003;15(6):523–30.

Sabaté E. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. ISBN 92 4 154599 2

Acknowledgements

The participation of the following researchers in the study is appreciated:

Investigators 25Q: Antonio Alcántara Montero; Camelia Alina Clep; Juan Manuel Almeida Felipe; Amelia Álvarez Barrial; Margarita Álvaro Pardo; Belén Aranda Zamora; Martín Zacarías Arcas Molina; Miguel Ángel Benítez Rosario; Carlos Burguera Baldovi; Ana Callejo Orcasitas; María Victoria Callejón Martínez; María Luz Cánovas Martínez; Joaquín Cartagena Sevilla; Miguel Casals Merchán; Rafael Cobos Romana; Joan Coma Alemany; José Carlos Cordeiro Da Silva; Juan Luis Cordero López; Josefa Costillo Rodríguez; Rafael De Alba Moreno; Ana Bella de la Calle Gil; José De la Cueva Aguilera; Alejandro de Luis Lillo; María Candelas de Madariaga Núñez; Javier Manuel del Saz de la Torre; Ernesto Delgado Cidranes; Diego Díaz Cárdenas; Enrique Domínguez Suárez; Iñaki Erquicia Peralt; Mariano Fernández Baena; Alfredo Fernández Esplá; Julia M Ferreras Zamora; Jose María Fraile Vicente; Julio Gallego González; Modesto García Escobar; Juan Antonio García García; Martín García Muñoz; José Giménez Viudes; Laura Gómez Gila; José Luis Gómez Palonés; José Manuel González Mesa; Mª del Mar Hernández García; Patricia Hernández Puiggros; Inmaculada Herrador Montiel; Gustavo Illodo Miramontes; Rosa Izquierdo Aguirre; Ziortza Landaluze Bueno; Xelo Lapuebla Ferri; Francisco Leal Quiñones; Juan Pablo Leiva Santos; Dolores López Alarcón; María López Gómez; Mercedes López Luque; Ramón López Martín; Ana Esther López Pérez; José Manuel López-Millán Infantes; Antonio Lucas Hernández; Jesús Maldonado Contreras; César Margarit Ferri; Leandro Maroto Gómez; Laura Judith Martínez Álvarez; Ángel Martínez Navas; Olga Martínez Pérez; Josep Martos Gutiérrez; Ana Belén Mencías Hurtado; Jesús María Mirasol García; Luis Alfonso Moreno Cuartas; Mª José Moreno Vázquez; Marcelino Mosquera Pena; Mercedes Mozas Calabaza; Juan Francisco Mulero Cervantes; Inmaculada Muro Castillo; Gemma Novas Brach; Antonio Ojeda Niño; Anna Padrol Munté; Inmaculada Concepción Pardillos Calatayud; Magdalena Pasek; Raquel Peláez Romero; Rosa María Pereda Marín; Concepción Pérez Hernández; Raquel Pérez Maganto; Fátima Pérez Martín; Inmaculada Raja Casillas; Marco Aurelio Ramirez Huaranga; María de la Vega Reyes García; Paloma Ricós Bugeda; Manuel Robles Romero; María Rodríguez Losada; Consuelo Rodríguez Rodríguez; Juan Romero Cotelo; Feliciano Sánchez Domínguez; Ángel Enrique Sánchez Jiménez; Daniel Sánchez Posada; María Milagrosa Santana Pineda; Luis Javier Santos Iglesias; Eduardo Terrer Galera; Pablo Tordera Higón; Caridad Estrella Torrens Hernández; José Manuel Trinidad Martín-Arroyo; Marina Isabel De Lourdes Ugarte; Alonso Urbano Castillo; Garbiñe Urtusagasti Orue; Pablo Villacé Gallego; Francisco Jesús Villegas Estévez; Frank Walter; Ana Cristina Zamora Moliner.

Funding

This work was supported by Kyowa Kirin Farmacéutica, S.L.U., Spain. The sponsor was involved in the design of the study, the interpretation of data results, and in the decision to submit the article to publication.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its Additional files 1 and 2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

FVE, MDLA, AJJL, and ASY designed the study, interpreted the study results, reviewed and approved the final manuscript. BSL conducted the design, monitoring, statistical analysis, and wrote the final manuscript. The 25Q-Study group reviewed and approved the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

A retrospective observational study was designed. The Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Consorcio Hospitalario Provincial de Castellón (Spain) approved the study on 1 June 2016. As the information collected in the study was pooled data, it was not applicable to obtain individual informed consent from patients for whom the clinical histories were reviewed.

The study was carried out in accordance with the Good Epidemiology Practice guidelines of the International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology. Likewise, the study was conducted according to the basic ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, where applicable.

Competing interests

FVE and MDLA perceived a fee for the design, conduction, and coordination of the study from Kyowa Kirin Farmacéutica, S.L.U.

AJJL and ASY are employees of Kyowa Kirin Pharmaceutical, S.L.U.

BSL was contracted by Kyowa Kirin Farmacéutica, S.L.U.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

25 questionary-research data. (XLS 97 kb)

Additional file 2:

Variables file description. (DOC 25 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Villegas-Estévez, F., López-Alarcón, M.D., Jiménez-López, A.J. et al. Evaluation of the quality of care of oncologic patients with pain in palliative and pain units based on the Achievable Benchmarks of Care (ABC): project 25Q. Saf Health 4, 5 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40886-018-0072-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40886-018-0072-2