Abstract

Background

Leiomyosarcoma (LMS) of the inferior vena cava (IVC) is a rare malignancy that originated from the smooth muscle tissue of the vascular wall. Diagnoses, as well as, treatment of the disease are still challenging and to date, a radical surgical resection of the tumor is the only curative approach.

Case report

We report on the case of a 49-year old male patient who presented with suddenly experienced dyspnea. Besides bilateral pulmonary arterial embolism, a lesion close to the head of the pancreas was found using CT scan, infiltrating the infrahepatic IVC. Percutaneous ultrasound-guided biopsy revealed a low-grade LMS. Intraoperatively, a tumor of the IVC was observed without infiltration of surrounding organs or distant metastases. Consequently, the tumor was removed successfully, by en-bloc resection including prosthetic graft placement of the IVC. Histological workup revealed a completely resected (R0) moderately differentiated LMS of the IVC.

Conclusion

LMS of the infrahepatic IVC is an uncommon tumor, which may present with dyspnea as its first clinical sign. Patients benefit from radical tumor resection. However, due to the poor prognosis of vascular LMS, a careful follow-up is mandatory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sarcomas are connective tissue origin tumors representing only 1% of all adult malignancies [1]. Leiomyosarcoma (LMS) is a subtype of soft tissue sarcomas (STS) which accounts for less than 8–20% of all STS and mostly affects the gastrointestinal tract, uterus, skin as well as blood vessels [2, 3].

Primary LMS of the inferior vena cava (IVC) is a rare type of vascular LMS with only a few hundred cases in the literature since its first description in 1871 by Perl as an autopsy finding [4, 5]. Initially, these neoplasms were considered inoperable; however, improvements in surgical techniques and perioperative management allowed to the first surgical tumor resection which was carried out in 1928 by Melchior [6].

The diagnosis is mostly challenging because of untypical clinical symptoms [4]. In addition, the use of modern imaging methods is also complex and only histopathological examination can clearly identify this malignancy [7, 8]. Radical surgical approach predominates as the only curative therapy option by complete resection with a safety margin; however, still with a poor prognosis with median overall survival of around 23–71 months [4, 9,10,11].

Case report

A 49-year-old male patient presented with suddenly experienced dyspnea in the internal medicine emergency unit. His medical history included a stage IIA nodular sclerosing type of classical Hodgkin lymphoma (NSCHL), splenectomy at the age of 9, implantation of a cardiac resynchronization therapy pacemaker (CRT-P) at the age of 35, a stage IA/E diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) near the left maxillary tuber at the age of 37, and bioprosthetic aortic valve replacement at the age of 44. Transthoracic echocardiogram showed a normal ejection fraction of 60% with normal positioned CRT-P with good function. Furthermore, laboratory analysis revealed D-Dimer 6.32 mg/l. Deep vein thrombosis was excluded by the duplex sonography examination.

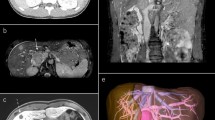

Subsequent computed tomography (CT) scan revealed bilateral pulmonary arterial embolism in lower lobes. Moreover, a solid tumorous mass close to the pancreas head was observed, along with infiltration into and a significant portion of thrombus material inside of the IVC (Fig. 1). A positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) scan revealed a glucose hypermetabolic mass without any evidence of distant metastases (Fig. 2). Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) revealed an inhomogeneous, hypoechoic tumor (42 × 30 mm) with infiltration of the IVC without abnormal findings in the head of the pancreas. A EUS-guided fine needle biopsy was not feasible due to crossing blood vessels. For this reason, a percutaneous ultrasound-guided biopsy was done and a low-grade LMS was diagnosed histologically.

After extensive diagnosis, the case was presented in the interdisciplinary tumor board. By taking into account the patient’s general condition, a decision on surgical treatment was made. Using midline laparotomy, the tumor region was exposed after Cattell maneuver (Fig. 3a). Hereby, the tumor mass was identified in the retroperitoneal space, being infrarenal part of the IVC (segment I), whereas the duodenum and head of the pancreas were separated from the tumor without problems. Then, en-bloc resection of the tumor was performed using two Satinsky vena clamps (Fig. 3b). Prosthetic replacement of the IVC was performed using a 20-mm diameter ring-enforced polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) vascular graft (Fig. 3c).

Intraoperative situs. a Presentation of the IVC after Cattell maneuver (blue vessel loops on the proximal side infrarenal and on the distal side prebifurcation, yellow vessel loop for isolation of the right ureter). b Situs after en-bloc tumor resection between Satinsky vena clamps. c IVC-reconstruction using a 20-mm PTFE vascular graft

Thrombotic material, the putative source of pulmonary artery embolism, was found adherent to the cranial margin of an intraluminal mass (Fig. 4). The IVC wall contained a 4.2 × 3.8 × 3.3 cm predominantly intraluminal mesenchymal tumor (Fig. 5). Layers of connective tissue and endothelium clearly separated the tumor cells from the bloodstream. Despite the history of NSCHL and DLBCL, no traces of Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) could be detected in the lesion, ruling out an EBV-associated smooth muscle tumor (EBV SMT) [14,15,16,17,18]. The tumor was hence classified as a moderately differentiated LMS of the IVC. The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient was discharged at postoperative day 9.

Histopathological findings. All staining was carried out on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue. a Monoclonal antibodies to the Ki67 antigen (Anti-Ki67) were applied to flag cells in the G1, S, G2, and M phase of their cell cycle, but not in the resting phase G0. Despite the fact that intraobserver and interobserver reproducibility of the visual assessment of Ki67 expression in IHC are low [12], there was a consensus that the tumor showed considerable activity. b The tumor cells revealed a specific, strong, and diffuse cytoplasmatic reactivity for antibodies to smooth muscle actin (Anti-α-Actin) as seen in cases of LMS. c The cytoplasmatic reactivity of tumor cells with antibodies to desmin (Anti-Desmin) as shown here might be associated with improved survival as the expression of this antigen can help predict the outcome by segregating moderately differentiated LMS into two groups, those that behave like well-differentiated tumors by expressing desmin and those that behave like poorly differentiated tumors by not expressing it [13]. d Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining revealed tumor cells with pleomorphic nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasmata

A follow-up CT scan 8 months after surgery, however, revealed evidence of multiple, bilobar, intense glucose hypermetabolic liver metastases but no relapse at the primary tumor site. For this reason, the patient underwent chemotherapy with gemcitabine/docetaxel (two cycles) and hereafter with gemcitabine as monotherapy in terms of an individual treatment approach. No pulmonary filiae have been found so far, supporting the notion that tumor cells might not have contributed to the clinical course of the aforementioned bilateral pulmonary arterial embolism. Thereby, the patient is alive 20 months after surgery, with a stable disease of the liver metastases without any other distant metastases and local tumor recurrence.

Discussion

LMS of the IVC is a rare malignant tumor. Due to the slow growth and mutable anatomic appearance, this malignancy clinically presents with ambiguous signs or is just asymptomatic [19]. Not surprisingly, approximately 10% of all cases are diagnosed incidentally [4]. In the same line of evidence and therefore highly remarkable, the first clinical sign of the tumor disease in our patient was dyspnea due to recurrent episodes of embolism, and certain diagnostic tools were required to identify the causative source of embolism.

Once diagnosed, these neoplasms were mostly regarded as inoperable tumors. Since the first surgical tumor resection by Melchior in 1928, however, and due to several improvements in surgery, anesthesiology and intensive care medicine, complete tumor resection with tumor-free margin is considered the primary and only curative treatment approach nowadays [6, 20].

With respect to the literature, data on this tumor entity is rare with less than 1.000 published cases. Interestingly, only a few reports comprise a higher number of patients. In 1991, Mingoli et al. were the first to publish a series of 144 patients suffering from LMS of the IVC [21, 22]. Most patients were female (about 2/3) with a median age of 55 years. The clinical symptoms were unspecific or almost lacking. Due to its rarity in consequence, they recommended the establishment of an international registry to study the pathogenesis and the natural history of this disease. In 1997, they again reported on 218 patients suffering from LMS of the IVC and who underwent radical surgical resection [21, 22]. Two decades later in 2015, Wachtel et al. reported on almost 377 cases [4].

Both reported that the majority of patients complained of unspecific abdominal pain (up to 60%) besides asymptomatic features [4]. The respiratory complaint was described by Wachtel et al. as a non-specific clinical symptom in 5.1% of the cases [4]. Not surprisingly in this context and typically for the heterogeneity of clinical presentation is the fact that LMS may even present with dyspnea as first clinical sign due to recurrent episodes of embolism as a consequence of intraluminal tumor growth and formation of local thrombosis, as occurred in our patient [8, 23,24,25].

Despite the fact that EBV may be associated with various malignancies [17, 18, 26,27,28], combinations of Hodgkin and/or non-Hodgkin lymphoma with LMS may occur without the virus. EBV negativity in our patient suggests that the clinical course was not modified by the virus.

Meaningful seems to be the site of IVC affection by the tumor in terms of patient survival. In this context, three groups of IVC segments were classified according to tumor localization: segment I—infrarenal IVC, segment II—inter- and suprarenal IVC, segment III—suprahepatic IVC and cardiac involvement [22, 29]. Patients with segment II tumor localization experienced the highest 5-year survival rates (56.7%) compared with patients with segment I tumor localization (37.8%), as reported by Mingoli et al. [30]. Additionally, segment III tumors were mostly inoperable and the median survival was only one month in this group of patients [30]. The high survival in the segment II group might be explained by the assumption that a tumor which is located near to abdominal organs and structures might earlier experience clinical symptoms, e.g., by tumor compression, resulting in early diagnosis and therapy. Remarkably, both Wachtel et al. and Mingoli et al. had described no survival benefit from radiation and chemotherapy treatment [4, 31]. Although there is no evidence showing a long-term survival improvement from adjuvant therapy, it can be considered an individual treatment approach to reduce or stabilize the recurrence of the disease [32, 33].

Conclusion

LMS of the IVC is a rare disease and still challenging, not only to diagnose but also to cure. It is characterized by a variety of different, unspecific clinical signs. Once diagnosed, these patients should be discussed in a multidisciplinary tumor board to evaluate tumor resectability. In spite of the absence of clinical trials, the actual data support surgical resection of the tumor as a unique option for treatment. Therefore, complete tumor resection is considered the only curative therapy approach, since chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy by themselves tend to show no better survival rates [5, 11, 31, 34,35,36]. Indeed, radical surgical treatment can be beneficial, provided a precise patient selection and an experienced, interdisciplinary team.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CD:

-

Cluster of differentiation

- CRT-P:

-

Cardiac resynchronization therapy pacemaker

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- DLBCL:

-

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

- EBV:

-

Epstein-Barr virus (syn.: type 4 human herpesvirus, HHV-4)

- EUS:

-

Endoscopic ultrasound

- FFPE:

-

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

- FNCLCC:

-

French Federation of Comprehensive Cancer Centers

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- ISH:

-

In situ hybridization

- IVC:

-

Inferior vena cava

- LMP:

-

Late membrane protein of EBV

- LMS:

-

Leiomyosarcoma

- NHL:

-

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- NSCHL:

-

Nodular sclerosing type of classical Hodgkin lymphoma

- PET-CT:

-

Positron emission tomography–computed tomography

- PTFE:

-

Polytetrafluoroethylene

- TNM:

-

A classication system to describe size and spread of cancer

- pTNM:

-

TNM classification based on histopathologic examination

- STS:

-

Soft tissue sarcomas

- UICC:

-

Union Internationale Contre le Cancer

References

Burningham Z, et al. The epidemiology of sarcoma. Clinical sarcoma research. 2012;2(1):14.

Saltus CW, et al. Epidemiology of adult soft-tissue sarcomas in Germany. Sarcoma. 2018;2018:5671926.

Jain S, et al. Molecular classification of soft tissue sarcomas and its clinical applications. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2010;3(4):416–28.

Wachtel H, et al. Outcomes after resection of leiomyosarcomas of the inferior vena cava: a pooled data analysis of 377 cases. Surg Oncol. 2015;24(1):21–7.

Perl, L., Virchow, R., Ein Fall von Sarkom der Vena cava inferior. 1871. 53(4): p. 378-383.

Melchior E. Sarkom der Vena cava inferior. Deutsche Zeitschrift für Chirurgie. 1928;213(1):135–40.

Wachtel H, et al. Resection of primary leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava (IVC) with reconstruction: a case series and review of the literature. J Surg Oncol. 2015;111(3):328–33.

Mastoraki A, et al. Challenging diagnostic and therapeutic modalities for leiomyosarcoma of inferior vena cava. Int J Surg. 2015;13:92–5.

Stilidi IS, et al. Surgical treatment of patients with leiomyosarcoma of inferior vena cava. Khirurgiia (Mosk). 2017;10:4–12.

Meyer F, et al. Mid-term, relatively tumor-stable outcome after an initially successful interdisciplinary surgical intervention with locally achieved R0 resection status including a multimodal therapeutic concept of a metastasized leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2013;163(11-12):295–302.

Cananzi FC, et al. Role of surgery in the multimodal treatment of primary and recurrent leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava. J Surg Oncol. 2016;114(1):44–9.

Jonat W, Arnold N. Is the Ki-67 labelling index ready for clinical use? Ann Oncol. 2011;22(3):500–2.

Demicco EG, et al. Progressive loss of myogenic differentiation in leiomyosarcoma has prognostic value. Histopathology. 2015;66(5):627–38.

Castillo JJ, et al. EBV-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified: 2018 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification and management. Am J Hematol. 2018;93(7):953–62.

Huang Q, et al. Composite recurrent hodgkin lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: one clone, two faces. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;126(2):222–9.

Vockerodt M, et al. Epstein-Barr virus and the origin of Hodgkin lymphoma. Chin J Cancer. 2014;33(12):591–7.

Tan CS, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated smooth muscle tumors after kidney transplantation: treatment and outcomes in a single center. Clin Transpl. 2013;27(4):E462–8.

Takei H, Powell S, Rivera A. Concurrent occurrence of primary intracranial Epstein-Barr virus-associated leiomyosarcoma and Hodgkin lymphoma in a young adult. J Neurosurg. 2013;119(2):499–503.

Lopez-Ruiz JA, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava. Case report and literature review. Cir Cir. 2017;85(4):361–5.

Teixeira FJR Jr, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava: Survival rate following radical resection. Oncol Lett. 2017;14(4):3909–16.

Mingoli A, et al. The effect of extend of caval resection in the treatment of inferior vena cava leiomyosarcoma. Anticancer Res. 1997;17(5B):3877–81.

Mingoli A, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava: analysis and search of world literature on 141 patients and report of three new cases. J Vasc Surg. 1991;14(5):688–99.

Fernandez HT, et al. Inferior vena cava reconstruction for leiomyosarcoma of Zone I-III requiring complete hepatectomy and bilateral nephrectomy with autotransplantation. J Surg Oncol. 2015;112(5):481–5.

Nabati M, Azizi S. Leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava presenting as a cardiac mass. J Clin Ultrasound. 2018;46(6):430–3.

Reddy VP, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava: a case report and review of the literature. Cases J. 2010;3:71.

McClain KL, et al. Association of Epstein-Barr virus with leiomyosarcomas in young people with AIDS. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(1):12–8.

Shannon-Lowe C, Rickinson A. The Global Landscape of EBV-Associated Tumors. Front Oncol. 2019;9:713.

Purgina B, et al. AIDS-Related EBV-Associated Smooth Muscle Tumors: A Review of 64 Published Cases. Pathol Res Int. 2011;2011:561548.

Kulaylat MN, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava: a clinicopathologic review and report of three cases. J Surg Oncol. 1997;65(3):205–17.

Mingoli A, et al. International registry of inferior vena cava leiomyosarcoma: analysis of a world series on 218 patients. Anticancer Res. 1996;16(5B):3201–5.

Mingoli A, et al. Surgical treatment of inferior vena cava leiomyosarcoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211(1):145–6.

Motodaka H, et al. Simultaneous surgery for inferior vena cava leiomyosarcoma with multiple hepatic metastases: a justified challenge. Am J Case Rep. 2019;20:902–7.

Jeong S, et al. Clinical outcomes of surgical resection for leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava. Ann Vasc Surg. 2019;61:377–83.

Kotelis D, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava. Chirurg. 2007;78(5):469–70 472-3.

Xu J, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the Inferior vena cava in an HIV-positive adult patient: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Case Rep. 2017;18:1160–5.

Kieffer E, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava: experience in 22 cases. Ann Surg. 2006;244(2):289–95.

Acknowledgements

The authors do not have funding interests.

Funding

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors do not have competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gafarli, S., Igna, D., Wagner, M. et al. Dyspnea due to an uncommon vascular tumor: leiomyosarcoma of the infrahepatic vena cava inferior. surg case rep 6, 136 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-020-00896-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-020-00896-9