Abstract

Background

Catheter ablation is a non-medication therapy for atrial fibrillation, and during the procedure, warfarin is withdrawn in the preoperative period to prevent the risk of bleeding. In case of emergency, vitamin K2 can be intravenously administered to antagonize the anticoagulant activity of warfarin. The aims of this study were to conduct population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling for retrospective clinical data and to investigate the effect of vitamin K2 on the anticoagulant activity of warfarin in the perioperative period of catheter ablation.

Methods

A total of 579 international normalized ratio (INR) values of prothrombin time from 100 patients were analyzed using the nonlinear mixed-effects modeling program NONMEM. A 1-compartment model was adapted to the pharmacokinetics of warfarin and vitamin K2, and the indirect response model was used to investigate the relationship between plasma concentration and the pharmacodynamic response of warfarin and vitamin K2. Since no plasma concentration data for warfarin and vitamin K2 were available, 3 literally available pharmacokinetic parameters were used to simultaneously estimate 1 pharmacokinetic parameter and 5 pharmacodynamic parameters.

Results

The population parameters obtained not only successfully explained the observed INR values, but also indicated an increase in sensitivity to warfarin in patients with reduced renal function. Simulations using these parameters indicated that vitamin K2 administration of more than 20 mg caused a slight dose-dependent decrease in INR on the day of catheter ablation and a delayed INR elevation after warfarin re-initiation.

Conclusions

A pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model was successfully built to explain the retrospective INR data during catheter ablation. Simulation studies suggest that vitamin K2 should be administered with care and that more than 20 mg is unnecessary in the preoperative period of catheter ablation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Atrial fibrillation is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia and a major cause of stroke [1, 2]. In order to prevent stroke, an anticoagulant drug, warfarin, is usually used since aspirin was proven ineffective in retrospective analyses [3]. The anticoagulant effect of warfarin does not always correlate with its dose, and polymorphisms in cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2C9 and vitamin K epoxide reductase complex subunit 1 (VKORC1) genes have been proven to influence interindividual variability in the optimal doses, in addition to patients’ primary diseases and characteristics such as age or ethnicity [4, 5]. In Japanese patients, warfarin dose adjustments based on their prothrombin time, an international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.6–2.6 (age ≥ 70 years) or 2.0-3.0 (age < 70 years), are recommended for effective therapy to avoid life-threatening bleeding [6, 7]. When hemorrhagic complications occur, warfarin withdrawal is required and vitamin K2 or fresh frozen plasma administration is recommended [8–10].

In atrial fibrillation treatment, antiarrythmic agents are often used, while catheter ablation is also an available option as a non-medication therapy [2]. When catheter ablation, an invasive procedure for complete cure of atrial fibrillation, is selected, anticoagulant therapy with warfarin is withdrawn in the preoperative period to prevent the risk of bleeding, although catheter ablation is sometimes performed in periprocedural therapeutic anticoagulation with warfarin if possible. In some patients, discontinuation of warfarin is not sufficient to lower the INR to the required level before catheter ablation. In such cases, vitamin K2 is intravenously administered to antagonize the anticoagulant activity of warfarin resulting in prompt recovery of INR to a safe level. Some reports have mentioned the use of pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic models for an anticoagulant drug and have conducted population analyses; however, only warfarin was investigated using these models [11, 12]. The effect of vitamin K2 dose on controlling the anticoagulant activity of warfarin during the perioperative period of catheter ablation has not yet been reported. The aims of this study are to build a population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model not only for warfarin, but also for vitamin K2, by using routine clinical data of patients who had been diagnosed with atrial fibrillation and received a catheter ablation, and to obtain information on the optimal vitamin K2 dose in the preoperative period before catheter ablation.

Methods

Patients and data studied

We retrospectively collected data from patients who have had a catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation at the Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Kyoto University Hospital from January to December in 2008. During this period, 126 Japanese patients underwent catheter ablation, and 111 of these patients were treated with warfarin on the day of admission. A total of 100 patients whose INR values were between 1.0 and 3.0 in the hospitalization period were included in this study. We used 579 INR values obtained from 100 patients during the perioperative period. Clinical laboratory data and medication history for the patients studied were collected from electrical medical records. No patients were taking any medications that may have clinically significantly altered the pharmacokinetics of warfarin, except 4 patients with amiodaron and 1 patient with bucolome [13, 14].

Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model building

A 1-compartment model was adopted to the pharmacokinetics of warfarin and vitamin K2 as follows (Fig. 1):

Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model of warfarin and vitamin K2. In this model, Cp 1 and Cp 3 represent the plasma concentration of warfarin and vitamin K2, respectively; Vd 1 and Vd 3 represent the distribution volume; and k 10 and k 30 represent the first-order elimination rate constant for each drug. The zero-order synthesis and first-order degradation rate constant for clotting factors are shown as k s and k d , respectively, and IC 50, E max and EC 50 represent 50 % inhibitory concentration of warfarin, maximum effect of vitamin K2 and 50 % effective concentration of vitamin K2, respectively

where Cp 1 and Cp 3 represent the plasma concentration of warfarin and vitamin K2, respectively; and Vd 1 and Vd 3 represent the distribution volume; and k 10 and k 30 represent the elimination rate constant for each drug, respectively. Since no plasma concentration data were available for warfarin and vitamin K2, and INR values were the available data for this study, reported pharmacokinetic parameters for warfarin in Japanese patients [11] and the distribution volume for vitamin K2 in the product information (Eisai Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) were used in the analysis: k 10 = 0.0129 (1/h), Vd 1 = 0.183 (L/kg) and Vd 3 = 0.051 (L/kg). Therefore, k 30 was the only pharmacokinetic parameter to be estimated in this analysis.

The indirect response model was used to explain the relationship between plasma concentration and pharmacodynamic response of warfarin and vitamin K2 [11, 14–16]. In this model, the amount of clotting factors was described using a zero-order synthesis rate constant (k s ) and a first-order degradation rate constant (k d ) under the hypothesis that coagulant activity was proportional to the amount of clotting factors (Fig. 1). Since both warfarin and vitamin K2 target the same enzyme that is responsible for clotting factor synthesis [17], the maximum effect models were adopted to describe stimulatory and inhibitory activities of these drugs, respectively, as follows:

where k s , k d , IC 50 , E max, and EC 50 represent synthesis rate constant (%/h), degradation rate constant (1/h), 50 % inhibitory concentration of warfarin (μg/mL), maximum effect of vitamin K2 (no unit), and 50 % effective concentration of vitamin K2 (μg/mL) were used, respectively (Fig. 1). The Hill coefficient used in the previous study [11] was not included in the present model to simplify the pharmacodynamic model. Since only INR values were collected in this study, thrombotest (TT) values were calculated according to Equation 4 using values provided from literature [18]:

Since the predicted values were outputted by the nonlinear mixed-effects modeling program (NONMEM) [19] using TT values, these were then converted into INR values when necessary by solving the quadratic equation obtained from Equation 4.

The population pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analysis was performed using the NONMEM (version VI), using the first-order conditional estimation method [19]. In this study, exponential error models for both inter- and intraindividual variability were chosen as follows:

where P ij is the i-th individual pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic parameter for patient j; P pop,i is the i-th population mean parameter; and η ij is the individual random perturbation from the population mean parameter that is distributed with a mean of zero and variance ωι 2. TT jk is the observed TT value at time k for patient j; TT * jk is the corresponding predicted TT value; and ε jk represents the independent identically distributed error with a mean of zero and variance of σ2 for the TT value.

The number of η used in the model was determined by the method of minimum Akaike information criterion (AIC) estimation [20].

where OBJ is the objective function values calculated using the NONMEM and M is the number of independently adjusted parameters within the model.

Next, the influence of renal function on each parameter was examined using Equation 8, by the forward selection method.

where RF = 1 if serum creatinine was higher than our in-hospital reference value, namely 1.1 mg/dL or higher for men, and 0.8 mg/dL or higher for women, otherwise RF = 0. P * pop,i is the i-th population mean parameter in the patient whose serum creatinine is within our in-hospital reference value. The parameter set that had the smallest objective function value was selected, and the null hypothesis that θ was not statistically different from unity was examined using the likelihood ratio test. A difference of 7.88 in OBJ with 1 degree of freedom was used to measure statistical significance (P < 0.005 by the chi-squared distribution).

Simulation for INR transition

(A) Effect of vitamin K2 dose

Simulations were carried out using the obtained population mean parameters based on a typical patient whose body weight was 50 kg with/without renal failure. The maintenance dose of warfarin was set to 3 mg/day (7 PM) and was stopped on day −1 (the day prior to the operation), and 5 mg/day was administered for 2 days after the operation as a loading dose, followed by a maintenance dose of 3 mg/day. Vitamin K2 was administered at 20 mg 0, 1, 2, or 3-times every 4 hours after 4 PM on day −1 with the total dose administered ranging from 0 mg to 60 mg.

For quantitative evaluation, we obtained 4 parameters, namely ∆INR, 1st loading, 95 % recovery, and INR/day. The ∆INR represents the difference in INR values between before warfarin withdrawal and before the loading dose; the 1st loading represents an INR increase after the first warfarin loading dose; and the 95 % recovery represents the time needed for INR elevation in the postoperative period up to 95 % of the preoperative steady state INR value. In addition, INR/day was calculated by dividing ∆INR by 95 % recovery (day).

(B) Effect of warfarin dose

Simulations with various warfarin maintenance doses were conducted. As a maintenance dose, 3 to 6 mg of warfarin was administered and it was stopped on day −1 without vitamin K2 administration. Warfarin (2 mg) was added to each maintenance dose as a loading dose, and it was administered for 2 days after the operation, followed by each maintenance dose. Cases where 20 to 60 mg of vitamin K2 was administered were also simulated.

(C) Effect of interindividual variability

Simulations were also conducted using several parameter sets in which 1 of the mean parameters was altered using the interindividual variability (+ or – ω) from the population mean value. Warfarin and vitamin K2 doses were set to 3 and 20 mg, respectively, in each simulation.

Results

Patients’ characteristics and INR transitions

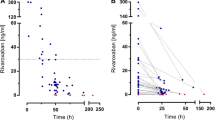

Table 1 shows the characteristics of patients used in this study. Each patient received anticoagulant therapy of 1 to 7 mg/day of warfarin to prevent thromboembolic events. The median initial INR value on the day of admission was 1.76, and the median maintenance dose before hospitalization and the median loading doses of warfarin after the operation were 3 and 5 mg, respectively. To antagonize warfarin after its withdrawal in the preoperative period, a total of 20 to 70 mg of vitamin K2, determined by the physician responsible, was intravenously administered to 76 patients before the operation. There were 4 patients with a total bilirubin concentration greater than our in-hospital reference value, but not substantially higher. Eight patients had an albumin concentration lower than our in-hospital reference values. Twenty-two patients had a serum creatinine concentration greater than our in-hospital reference value. Twenty-six patients had an estimated glomerular filtration rate from 30 – 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, and only 2 patients had below 30 mL/min/1.73 m2. Figure 2 shows the INR transitions of each patient from day −5 to day 10, where the day of operation was day 0. The INR values decreased during the preoperative period and gradually increased again during the postoperative period.

Model development

When interindividual variability was considered for all population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic mean parameters (η = 6), AIC was 3398. To simplify the model in which only η ks and η IC50 were included (η = 2), AIC was 3394, and was decreased to 3393 when another η for k 30 was included in the model (η = 3). Thus, the model with the minimum AIC value was adopted, which reflected the interindividual variability of k s , IC 50, and k 30 .

Next, a search for covariates of population mean parameters was conducted using the forward selection method. When the effect of serum creatinine on each population mean parameter was examined, significant effects of renal function on k s , k d , and IC 50 were observed (P < 0.005). Since the effect on IC 50 showed the largest −2 log likelihood difference (−2LLD) of 27.2, this effect was incorporated into the second step. At the second step, additional effects of renal function on other parameters were examined, but no significant differences were observed (−2LLD < 0.61). We also examined the effect of renal function on the IC 50 using the value of estimated glomerular filtration rate, but the model fitting was better in the model using serum creatinine. Therefore, we chose the model in which only IC 50 was affected by renal function as follows:

There were only 4 patients out of 100 patients whose total bilirubin concentration exceeded our in-hospital reference value, and those values were not remarkably high. Therefore, the effect of hepatic function on population mean parameters was not further examined. The anticoagulant effect of warfarin is generally considered to be associated with its unbound plasma concentration [10]. We examined the effect of serum albumin concentration on the IC 50 or k 10 , but we could not obtain any significant effects.

Table 2 shows the final population mean parameters obtained and inter- and intraindividual variability. The interindividual variability for k s , IC 50 and k 30 were 26.5 %, 37.9 %, and 41.4 %, respectively, and intraindividual variability was 28.2 % as a coefficient of variation (CV). In patients with decreased renal function, the IC 50 value was reduced to 61.4 % of those with normal renal function, suggesting enhanced sensitivity to warfarin.

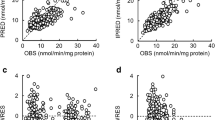

Validity of population mean parameters

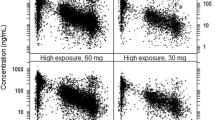

Figure 3 shows the plot of population or individual (post-hoc Bayesian) predicted versus observed TT. Although there was significant variability between the population predicted and observed TT, each plot individually predicted by the Bayesian method was closer to the unit line. The validation of the final population parameters was further confirmed by comparing the predicted INR values versus observed INR values (Fig. 4). Three typical patients were randomly selected each from 3 different groups classified by INR values on the day of admission (high, median and low), and their predicted values were compared to the observed values. The time course profiles predicted by the Bayesian method were closer to the observed values than those predicted by the population mean parameters were, although there was still some discrepancy between these plots.

Prediction of INR values by the population mean parameters and by the post-hoc empirical Bayesian method in 3 typical patients. The continuous, dashed and broken lines show the observed and predicted INR values using population mean parameters and using the Bayesian method, respectively. Three patients were randomly selected from the database based on the INR values (high, median, and low) on the day of admission

Effect of renal function on INR transition

Figure 5 shows the simulation curves for the effect of renal function. In a patient with decreased renal function, the INR value at a steady state rose from 1.65 in a patient with normal renal function to 1.99 with a maintenance dose of 3 mg/day (Fig. 5a). The INR transitions of a patient with decreased renal function showed more dynamic changes with variable vitamin K2 doses than those with normal renal function in the perioperative period. Table 3A shows the values from quantitative evaluation of Fig. 5. The ∆INR increased depending on the total dose of vitamin K2, while 95 % recovery was remarkably prolonged by the increased dose of vitamin K2. Specifically, without the administration of vitamin K2 to a patient with normal renal function, the 95 % INR recovery was 8 h, while it increased to 100 h when 20 mg of vitamin K2 was administered. The calculated INR/day also decreased from 0.39 (0 mg of vitamin K2) to 0.072 (20 mg of vitamin K2) in patients with normal renal function. In patients with decreased renal function, a similar but greater INR change compared with those with normal renal function is shown in Fig. 5 and Table 3A.

Effect of vitamin K2 doses on the INR transition in the perioperative period in a typical patient with normal a or decreased renal function b. A typical patient with body weight of 50 kg was administered warfarin and vitamin K2. In each simulation, the maintenance dose of warfarin was set to 3 mg/day and was stopped on day −1, and loading of 5 mg/day was carried out twice after catheter ablation, followed by the maintenance dose of 3 mg/day. Vitamin K2 was administered before catheter ablation up to 3 times 20 mg each as total of 0 to 60 mg. Continuous, dashed, dash-dotted and dotted lines show the administration of 0, 20, 40 and 60 mg of vitamin K2, respectively

Effect of warfarin dose on INR transition

Figure 6a shows the simulation curves with various warfarin maintenance doses. The INR values increased almost directly according to the increase in warfarin dose. In Table 3B, each quantitative index in Fig. 6a is shown, and the cases where 20 to 60 mg of vitamin K2 was administered are indicated. The ∆INR increased, ranging from 0.130 to 0.754 depending on both the warfarin maintenance dose and the vitamin K2 total dose. The 95 % recovery depended both on the warfarin maintenance dose and on the vitamin K2 total dose.

Effect of warfarin doses a or interindividual variability of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters b on INR transition in the perioperative period. In panel A, INR transitions were simulated wherein warfarin maintenance doses ranged from 3 to 6 mg without vitamin K2 administration. Warfarin was stopped on day −1, and resumed after catheter ablation with the addition of 2 mg to each maintenance dose as a loading dose twice, followed by each maintenance dose. Continuous, dashed, dash-dotted, and dotted lines show the simulations with the administration of 3, 4, 5, and 6 mg of warfarin, respectively. In panel B, INR transitions were simulated using parameter sets in which 1 of the parameters was changed based on interindividual variability (ω) from the population mean value. The warfarin maintenance dose and the vitamin K2 dose were set to 3 mg and 20 mg, respectively. The continuous, dotted, dashed, and dash-dotted lines show the simulations using all population mean values, and changed parameters for k s , IC 50, and k 30 , respectively. The fine and bold lines show the simulations using + and - ω change from each population mean value, respectively

Effect of interindividual variability on INR transition

Figure 6b shows the effects of interindividual variability on INR transition. The simulated curves suggested that the interindividual variability of k 30 had a relatively small effect on INR variability, while k s and IC 50 had greater effects although they varied by 26.5 % or 37.9 %, respectively, from each population mean value. The INR values under a warfarin maintenance dose of 3 mg ranged from 1.47 to 1.98, and INR values after warfarin withdrawal ranged from 1.23 to 1.55, depending on k s , IC 50, and k 30 values. Table 3C shows quantitative indices of the results of Fig. 6b. The ∆INR values ranged from 0.237 to 0.416, from 0.220 to 0.504, and from 0.294 to 0.310, when k s , IC 50 , and k 30 were increased or decreased by the interindividual variability from the population mean value, respectively. The interindividual variability of k s , IC 50 , and k 30 had similar effects on the 1st loading. Unlike the ∆INR values, the interindividual variability of k s and IC 50 had a small effect on the 95 % recovery, while the k 30 value strongly affected the 95 % recovery.

Discussion

It is widely known that the warfarin dose suitable for a patient varies among individuals and that careful monitoring of its anticoagulant activity is necessary for preventing excessive anticoagulation or hemorrhagic events [6, 7]. Vitamin K2 can effectively antagonize warfarin, for example, in the preoperative period and when life-threatening bleeding occurs [9]. Although the recommended dose of vitamin K2 was under 5 mg [9], 20–70 mg of vitamin K2 was administered to decrease the INR value in the preoperative period (Table 1). Thus, caution must be exercised to find a balance between over- and under-coagulation. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of warfarin have been studied since 1960’s [11, 12, 14, 21, 22], while combined pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic analyses of both warfarin and vitamin K formulations have not yet been reported. In the present study, we built a model that describes the pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics of these drugs for the first time. However, because this is a retrospective study wherein only patients’ pharmacodynamic data were used and because we converted the INR values to TT values while calculating the pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters, special attention should be paid when drawing conclusions from the results obtained herein. Additionally, the obtained pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters should be carefully treated, since these values greatly depended on the fixed pharmacokinetic parameters of warfarin and vitamin K2 in the model.

Final population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters had reasonably small relative standard errors except ω k30 2 (Table 3), and both individual predicted TT and INR values were well correlated with the observed values (Figs. 3 and 4), indicating that reliable population mean parameters were obtained in this study. Some patients had the INR values between 1.0-1.5 on the day of admission (Fig. 2). We could not check drug compliance in the patients before the hospitalization, but good compliance was expected in the hospital. Since the prediction bias of the TT was not observed against the time (data not shown), effects of non-compliance on the present results were considered to be small. Since coadministration of amiodarone or bucolome was reported to inhibit the warfarin metabolism mediated by CYP2C9 [13, 14], we examined the effect of these drugs on the k 10 . Although the coadministration of these drugs decreased k 10 , this effect did not reach a statistical significance level (−2LLD = 7.61 < 7.88). Therefore, we did not include the effect of amiodarone and bucolome in the final model. The estimated population mean parameters for k s , k d, and IC 50 were similar to those in a previous report [11], and interindividual variability for k s , IC 50 , and k 30 was minimal, although the intraindividual variability was quite significant.

The several simulations of INR transition by the obtained population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters showed that vitamin K2 could antagonize the anticoagulant activity of warfarin in a dose-dependent manner. While more than 20 mg of vitamin K2 showed only a small effect on the extent of INR decreases in the preoperative period, the time required for warfarin to exert its anticoagulation activity again in the postoperative period depended on the total dose of vitamin K2. An inability to anticoagulate promptly after the operation may lead to prolonged hospitalization and consequently decrease patients’ quality of life, as well as increase medical costs. Although it is important to examine the effect of less than 20 mg vitamin K2 on INR, we could not obtain clinical data using less than 20 mg vitamin K2. Effects of lower dose of vitamin K2 on INR remains to be examined in a future study.

In this study, we clarified the enhanced anticoagulant activity of warfarin in patients with decreased renal function. Warfarin is well known to inhibit the vitamin K-dependent synthesis pathway of coagulation factors in the liver and to be degraded in the liver [10]. Thus, great caution is required while using warfarin in patients with hepatic disorders [10]. According to the package insert of warfarin, caution is also required while use in those with renal dysfunction. Recent studies reported that renal function influences warfarin responsiveness and hemorrhagic complications [23, 24]. The maintenance warfarin dose was positively correlated with kidney function in Japanese patients [25]. Precise mechanisms for the enhanced sensitivity to warfarin in patients with decreased renal function should be investigated further in future studies.

Conclusions

We built and analyzed a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model of both warfarin and vitamin K2 by using retrospective clinical data during the catheter ablation. Simulations using the obtained population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters indicated that vitamin K2 should be administered with care and that more than 20 mg is unnecessary in the preoperative period of catheter ablation. Low-dose (5 mg or less) of vitamin K is recommended in the guideline [9].

Abbreviations

AIC, Akaike information criterion; Cp, plasma concentration; CYP, cytochrome P450; EC 50 , 50 % effective concentration; E max , maximum effect; IC 50 , 50 % inhibitory concentration; INR, international normalized ratio; k d , degradation rate constant; k s , synthesis rate constant; LLD, log likelihood difference; OBJ, objective function; TT, thrombotest; Vd, distribution volume, k, elimination rate constant; VKORC1, vitamin K epoxide reductase complex subunit 1.

References

Haïssaguerre M, Jaïs P, Shah D, Takahashi A, Hocini M, Quiniou G, Garrigue S, Le Mouroux A, Le Métayer P, Clémenty J. Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:659–66.

Wellens H. Atrial fibrillation--the last big hurdle in treating supraventricular tachycardia. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:944–5.

trial Fibrillation Investigators: Atrial Fibrillation, Aspirin, Anticoagulation Study; Boston Area Anticoagulation Trial for Atrial Fibrillation Study; Canadian Atrial Fibrillation Anticoagulation Study; Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Study; Veterans Affairs Stroke Prevention in Nonrheumatic Atrial Fibrillation Study. Risk factors for stroke and efficacy of antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation: Analysis of pooled data from five randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1449–57.

Higashi M, Veenstra D, Kondo L, Wittkowsky A, Srinouanprachanh S, Farin F, Rettie A. Association between CYP2C9 genetic variants and anticoagulation-related outcomes during warfarin therapy. J Am Med Assoc. 2002;287:1690–8.

Obayashi K, Nakamura K, Kawana J, Ogata H, Hanada K, Kurabayashi M, Hasegawa A, Yamamoto K, Horiuchi R. VKORC1 gene variations are the major contributors of variation in warfarin dose in Japanese patients. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;80:169–78.

Yasaka M, Minematsu K, Yamaguchi T. Optimal intensity of international normalized ratio in warfarin therapy for secondary prevention of stroke in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Intern Med. 2001;40:1183–8.

Joint Working Groups. The Japanese Circulation Society, The Japanese College of Cardiology, The Japanese Society of Electrocardiology, and The Japanese Heart Rhythm Society. Guidelines for pharmacotherapy of atrial fibrillation (JCS2013). 2013. http://www.j-circ.or.jp/guideline/pdf/JCS2013_inoue_h.pdf. Accessed 30 March 2016.

Joint working Groups. Guidelines for management of anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy in cardiovascular disease (JCS2004). Circ J. 2004;68 Suppl 4:1153–219.

The Haemostasis and Thrombosis Task Force for the British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines on oral anticoagulation: third edition. Br J Haematol. 1998;101:374–87.

Shetty H, Fennerty A, Routledge P. Clinical pharmacokinetic considerations in the control of oral anticoagulant therapy. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1989;16:238–53.

Sato S, Toda T, Yamazaki M, Hongo F, Kurosawa N, Owada E, Hatta E, Nakamura M, Nakanishi K, Okamoto F, Sakai K, Hirokami M, Hanawa N, Tanaka S. Warfarin maintenance dose estimation program “WfTDM” based on thrombo-test value. Jpn J Ther Drug Monit. 2006;23:10–6.

Hamberg AK, Dahl ML, Barban M, Scordo MG, Wadelius M, Pengo V, Padrini R, Jonsson EN. A PK-PD model for predicting the impact of age, CYP2C9, and VKORC1 genotype on individualization of warfarin therapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;81:529–38.

Holbrook AM, Pereira JA, Labiris R, McDonald H, Douketis JD, Crowther M, Wells PS. Systematic overview of warfarin and its drug and food interactions. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1095–106.

Osawa M, Hada N, Matsumoto K, Hasegawa T, Kobayashi D, Morimoto Y, Yamaguchi M, Kanamoto I, Nakagawa T, Sugibayashi K. Usefulness of coadministration of bucolome in warfarin therapy: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analysis using outpatient prescriptions. Int J Pharm. 2005;293:43–9.

Jusko WJ, Ko HC. Physiological indirect response models characterize diverse types of pharmacodynamic effects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1994;56:406–19.

Dayneka NL, Garg V, Jusko WJ. Comparison of 4 basic models of indirect pharmacodynamic responses. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1993;21:457–78.

Tie J, Stafford D. Structure and function of vitamin K epoxide reductase. Vitam Horm. 2008;78:103–30.

Gogstad G, Wadt J, Smith P, Brynildsrud T. Utility of a modified calibration model for reliable conversion of thromboplastin times to international normalized ratios. Thromb Haemost. 1986;56:178–82.

Beal SL, Boeckmann AJ, Sheiner LB. NONMEM Users Guides. NONMEM Project Group. San Francisco: University of California; 1992.

Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans Autom Control. 1974;19:716–23.

Sheiner LB. Computer-aided long-term anticoagulation therapy. Comput Biomed Res. 1969;2:507–18.

Nagashima RA, O’reilly RA, Levy G. Kinetics of pharmacologic effects in man: the anticoagulant action of warfarin. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1969;10:22–35.

Limdi NA, Beasley TM, Baird MF, Goldstein JA, McGwin G, Arnett DK, Acton RT, Allon M. Kidney function influences warfarin responsiveness and hemorrhagic complications. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:912–21.

Limdi NA, Limdi MA, Cavallari L, Anderson AM, Crowley MR, Baird MF, Allon M, Beasley TM. Warfarin dosing in patients with impaired kidney function. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56:823–31.

Ichihara N, Ishigami T, Umemura S. Effect of impaired renal function on the maintenance dose of warfarin in Japanese patients. J Cardiol. 2015;65:178–84.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms. Mio Kikuchi for her kind assistance of data entry and helpful suggestions.

Funding

None

Availability of data and materials

The data will not be shared because of human data.

Authors’ contributions

ZZ, IY, SO, and SS conceived the study, designed the protocol. ZZ, IY, SO, and YM carried out the study and drafted the manuscript. SS, MH, TK, AA, KI, and KM participated in interpretation of the data and contributed the discussions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

The present address of IY is the Department of Pharmacy, Kobe University Hospital.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare for this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine and Kyoto University Hospital (R0264).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, Z., Yano, I., Odaka, S. et al. Effect of vitamin K2 on the anticoagulant activity of warfarin during the perioperative period of catheter ablation: Population analysis of retrospective clinical data. J Pharm Health Care Sci 2, 17 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40780-016-0053-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40780-016-0053-8