Abstract

The 2011 Tohoku-oki earthquake generated a large tsunami that caused catastrophic damage along the Pacific coast of Japan. The major portion of the damage along the Pacific coast of Tohoku in Japan was mainly caused by the first few cycles of tsunami waves. However, the largest phase of the tsunami arriving surprisingly late in Hakodate in Hokkaido, Japan; that is, approximately 9 h after the origin time of the earthquake. It is important to understand the generation mechanism of this large later phase. The tsunami was numerically computed by solving both linear shallow water equations and non-linear shallow water equations with moving boundary conditions throughout the computational area. The later tsunami phases observed on southern Hokkaido can be much better explained by tsunami waveforms computed by solving the non-linear equations than by those computed by solving the linear equations. This suggests that the later tsunami waves arrived at the Hokkaido coast after propagating along the Pacific coast of the Tohoku region with repeated inundations far inland or reflecting from the coast of Tohoku after the inundation. The spectral analysis of the observed waveform at Hakodate tide gauge shows that the later tsunami that arrived between 7.5 and 9.5 h after the earthquake mainly contains a period of 45–50 min. The normal modes of Hakodate Bay were also computed to obtain the eigen periods, eigenfunctions, and spatial distribution of water heights. The computed tsunami height distributions near Hakodate and the fundamental mode of Hakodate Bay indicate that the large later phases are mainly caused by the resonance of the bay, which has a period of approximately 50 min. The results also indicate that the tsunami wave heights near the Hakodate port area, the most populated area in Hakodate, are the largest in the bay because of the resonance of the fundamental mode of the bay. The results of this study suggest that large future tsunamis might excite the fundamental mode of Hakodate Bay and cause large later phases near the Hakodate port.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

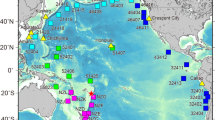

The 2011 Tohoku-oki earthquake (Mw9.1) generated a large tsunami, more than 20 m in height, which caused catastrophic damage along the Pacific coast of the Tohoku region in Japan (Mori and Takahashi 2012). The earthquake occurred at 14:46 on 11 March 2011. The first destructive tsunami arrived along the Sanriku Coast approximately 30 min after the origin time of the earthquake, and it arrived at the Sendai Plain approximately 70 min after the origin time (Japan Meteorological Agency 2012) (Fig. 1). Although tsunamis repeatedly arrived along the Pacific coast of the Tohoku region, destructive tsunamis typically occurred during the first few cycles of waves. Along the Pacific coast of Hokkaido in the northern part of Japan, the first tsunami wave arrived approximately 50 to 100 min after the earthquake. However, the largest tsunami wave in this region was typically a later phase of the tsunami. The largest tsunami, with a height of 2.4 m, arrived at mid-night in Hakodate when most people slept. Surprisingly, it arrived approximately 9 h after the earthquake (Fig. 1). We found several pictures of the tsunami inundation on the internet; they were taken during the night in Hakodate. Photographs of the tsunamis were also taken from the top of the building near the Hakodate harbor by NHK, the Japan Broadcasting Corporation. Figure 1 shows that the tide in Hakodate was much smaller than the tsunami waves and thus could not have caused the largest tsunami that occurred during the night. To support the importance of a long-time tsunami evacuations, it is important to understand the generation mechanism of the large later phases, particularly in Hakodate.

The slip distribution of the 2011 Tohoku-oki earthquake (Fujii et al. 2011) used to compute tsunamis in this study. The diamonds show the locations of the four tide gauges, that is, Hakodate, Tomakomai, Tomakomai-nishi, and Urakawa, to compare the observed and computed tsunami waveforms. The original tsunami waveform (without tide removal) observed in Hakodate (Japan Meteorological Agency 2012) is displayed in the middle

Previously, the 2004 Kushiro earthquake in Hokkaido also resulted in a relatively large later tsunami, which arrived approximately 1 h after the first, one in Urakawa. This later tsunami was generated by an edge wave that propagated across the large shallow water area off Cape Erimo, Hokkaido (Tanioka and Katsumata 2007). As far-field tsunamis, the 2006 earthquake caused large later tsunami waves, approximately 3 to 6 h after the first tsunami wave, along the Pacific coast of Japan. These later tsunamis were generated by the scattering of tsunami waves in the shallow region near the Emperor Seamounts in the Pacific Ocean (Koshimura et al. 2008; Tanioka et al. 2008). The 2006 Kurile earthquake also caused a large destructive later tsunami at Crescent City along the West Coast of the USA. This large later tsunami was generated by the combination of the shallow bathymetry near the Mendocino Escarpment off Crescent City, amplification of the tsunami heights by the oscillation at the continental shelf, and resonance of the Crescent City harbor (Horrillo et al. 2008; Kowalik et al. 2008). The 2011 Tohoku-oki tsunami also propagated across the Pacific Ocean and caused strong currents around the Hawaiian Islands that led to the closure of harbors for up to 38 h. The long duration of the strong currents was caused by the multiscale resonance of the shallow water surrounding the island chain, an island with interconnected shelves, and reefs and harbors (Cheung et al. 2013). Borrero et al. (2013) also reported tsunami waves arriving late in New Zealand, which were caused by the 2011 Tohoku-oki earthquake.

In this study, we computed 10 h of the 2011 Tohoku tsunami after the origin time of the earthquake. The observed tsunami waveforms recorded at several tide gauges along the Pacific coast on southern Hokkaido were compared with the computed ones to check that the later phases were well simulated. Subsequently, the generation mechanism of the large later tsunami wave in Hakodate was identified using the spectral analysis of the observed waveform, computed tsunami propagation snapshots off the Hakodate area, and resonance modes computed for Hakodate Bay.

Methods/Experimental

Waveform data

Original waveforms observed at two tide gauges in Hakodate and Urakawa (Fig. 1) were digitized from the report of the 2011 Tohoku-oki earthquake by the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA 2012). The observed digital tsunami waveform data, from which the ocean tides at a tide gauge in Tomakomai-nishi and a coastal wavemeter in Tomakomai were removed, were provided by the Nationwide Ocean Wave Information Network for Ports and Harbors (NOWPHAS); the data were obtained from the NOWPHAS website (https://nowphas.mlit.go.jp/prg/pastdata). The observed waveform data were compared with the computed tsunami waveforms to check that the observed later phases of the tsunami were well reproduced by those computed.

Tsunami simulation

Several source models for the 2011 Tohoku-oki earthquake have been suggested to explain the observed tsunami (e.g., Fujii et al. 2011; Gusman et al. 2012; Satake et al. 2013; Tappin et al. 2014; Yamazaki et al. 2018). In this study, the slip distribution estimated from the tsunami waveforms observed at tide gauges, offshore GPS wave gauges, and bottom pressure gauges near Japan (Fujii et al. 2011) (Fig. 1) was chosen as source model to numerically compute the tsunami.

The large later phases of the tsunami observed on southern Hokkaido, such as in Hakodate, did not directly propagate from the source but propagated along the Pacific coast of the Tohoku region as edge waves with repeated inundations far-inland or were reflected from the coast of Tohoku after the inundation. This indicates that the tsunami inundation computations along the Tohoku and Hokkaido coasts are necessary to reproduce the later phases of the observed tsunami in Hakodate on Hokkaido. In this study, first, the tsunami was numerically computed by solving the linear shallow water equation using a totally reflected boundary condition along the coast. Next, a tsunami numerical inundation computation was carried out by solving the non-linear shallow water equations using a moving boundary condition (Imamura 1996; Goto et al. 1997) throughout the entire computational area (Fig. 1). A homogeneous Manning’s roughness coefficient of 0.025 m−1/3s was assumed for the bottom surface. A grid system of 30 arc-seconds was used for these simulations. The time step was set to 0.5 s by satisfying the stability condition.

Spectral analysis of observed tsunami waveform

Temporal variations in the frequency or period of the tsunami waveform observed in Hakodate were computed using the method proposed by Rabinovich et al. (2006) and Rabinovich and Thomson (2007). This method is based on narrow-band filters, with a Gaussian window, Hn(ω), that isolates a specific center frequency, ωn = 2πfn:

The frequency resolution is controlled by the parameter α. The higher the value of α is, the better is the resolution in the frequency domain, but the poorer is the resolution in the time domain. In this study, we chose the same value as that used in Rabinovich et al. (2006), that is, α = 80. The demodulation of the observed tsunami time series produces a matrix of amplitudes of wave motions with columns representing times and rows representing periods.

Computation of the resonance modes for Hakodate Bay

The normal mode solution of the linear shallow water equation for an irregular bay has been numerically obtained by several researchers (Loomis 1975; Satake and Shimazaki 1987; Satake and Shimazaki 1988; Horrillo et al. 2008). Wu and Satake (2018) also computed normal mode solutions for the Sea of Japan. The wave equation for the linear shallow water approximation is as follows:

where h is the wave height, g is the gravitational acceleration, and d is the water depth. By assuming that the wave height periodically changes over time, h can be expressed as follows:

where Φ(x, y) is the spatial distribution of the wave height and ω is the angular frequency. Substituting (3) into (2), we obtain:

This is an eigenvalue problem with the eigenvalue λ and eigenfunction Φ(x, y). The symmetrical numerical form of Eq. (4), as shown by Loomis (1975), is solved to obtain the eigen period and eigenfunction Φ(x, y), that is, the spatial distribution of the water height.

Results

Tsunami numerical simulation

First, the tsunami waveforms computed by solving the linear shallow water equations were compared with the observations, as shown in Fig. 2. The first arrival waves of the observed tsunami waveforms occurring at four tide gauge stations, that is, Hakodate, Tomakomai, Tomakomai-nishi, and Urakawa, are relatively well explained by the computations. However, the later phases of the observed tsunami waveforms at these stations cannot be explained by the computed ones and are mostly overestimated. These later tsunamis arriving at the tide gauge stations on southern Hokkaido propagated along the Pacific coast of the Tohoku region with repeated inundations far inland or were reflected from the coast of Tohoku after the inundation. When large tsunamis propagate far inland, their energy is dissipated by the bottom friction. Therefore, the amplitude of the reflected tsunami is reduced. Thus, the tsunami numerical simulation based on the totally reflected boundary condition at the coast cannot reproduce the later phases of the observed tsunamis on southern Hokkaido. Hence, the computed results cannot be used to discuss the generation mechanism of the largest later tsunami phases observed in Hakodate.

Comparison of observed (blue) and computed (orange) tsunami waveforms by solving the linear shallow water equations at four tide gauges, in a Hakodate, b Tomakomai, c Tomakomai-nishi, and d Urakawa, shown in Fig. 1

Next, the tsunami waveforms computed by solving the non-linear shallow water equations using a moving boundary condition were compared with the observations, as shown in Fig. 3. In this case, not only the first wave but also the later phases of the observed tsunami waveforms at the four tide gauges were well explained by the computations. We therefore used the results of this simulation to analyze the largest later phase observed at the tide gauge in Hakodate.

Comparison of observed (blue) and computed (orange) tsunami waveforms by solving the non-linear shallow water equations with a moving boundary condition at the four tide gauges, in a Hakodate, b Tomakomai, c Tomakomai-nishi, and d Urakawa. The sinusoidal later tsunami phases that arrived in Hakodate between 7.5 and 9.5 h after the earthquake were investigated. Snapshots of the tsunami height distribution were taken 460, 480, 505, and 534 min after the earthquake (red lines) and were analyzed (Fig. 4)

To investigate the generation mechanism of the large sinusoidal waves that were observed between 7.5 h (450 min) and 9.5 h (570 min) after the earthquake, as shown in Fig. 3a, four snapshots of the tsunami height distribution taken near Hakodate 460, 480, 505, and 535 min after the earthquake occurrence were used (Fig. 4). The sinusoidal waves have a period of approximately 50 min. The snapshots are taken 460 and 505 min after the earthquake correspond to the bottom of two troughs in the time series of the tsunami waveform arriving in Hakodate between 450 and 570 min after the earthquake, as shown in Fig. 3a. Both snapshots of the tsunami height distributions show that the entire sea at Hakodate Bay subsided. However, the snapshots are taken 480 and 535 min after the earthquake correspond to the top of two peaks in the same time series of the tsunami waveform (Fig. 3a). Both snapshots of these tsunami height distributions show that the entire sea in Hakodate Bay rose in those cases. These results suggest that the resonance of the fundamental mode of Hakodate Bay is responsible for the generation of the large later phases at the tide gauge in Hakodate.

Snapshots of the tsunami height distribution around Hakodate taken 460, 480, 505, and 535 min after the earthquake, as shown in Fig. 3a

Spectral analysis of observed tsunami waveform in Hakodate

Figure 5 shows the result of the spectral analysis of the tsunami waveform in Hakodate; the period of the observed tsunami exhibits a temporal variation. The observed tsunami has a main period of 45–50 min throughout the record after its arrival, that is, about 90 min after the earthquake. The initial part of the tsunami during 3 h after the tsunami arrival has a shorter period of 25–28 min. However, this shorter period disappears in the later part of the tsunami. This indicates that the energy of the tsunami with a shorter period was dissipated more by the bottom friction during the inundation than that of the tsunami with a longer period. The large later tsunami that was observed between 7.5 h (450 min) and 9.5 h (570 min) after the earthquake contains a strong with a period of 45–50 min within a broader period of 45–58 min and a weak peak with a period of 32–38 min.

Normal mode calculation for Hakodate Bay

Figure 6 shows the results of the normal mode calculation for Hakodate Bay. In this calculation, a node was set at the mouth of Hakodate Bay as shown in Fig. 6. The fundamental mode has an eigen period of 49.60 min. The observed later tsunami had a main period near the eigen period (approximately 50 min), which indicates that the fundamental mode was excited by the 2011 Tohoku-oki tsunami (Fig. 3a and Fig. 5). The eigenfunction, that is, the spatial distribution of the water height, of the first mode in Fig. 6a is large near the Hakodate port area, which is the most populated region of Hakodate. The eigenfunction is also similar to the tsunami height distribution computed for Hakodate Bay (four snapshots in Fig. 4). This confirms that the first mode was excited by the 2011 Tohoku-oki tsunami and is the main cause of the large later tsunami phases observed in Hakodate. The second mode has an eigen period of 38.69 min (Fig. 5b). The eigenfunction of the second mode has another node off the Hakodate port at Hakodate Bay. The eigenfunction of the second mode in Fig. 5b is also large near the Hakodate port area. The eigen period of the second mode is similar to a weak peak with a period of about 32–38 min between 7.5 h and 9.5 h after the earthquake occurrence (Fig. 5). The second mode may therefore be slightly excited. The eigen periods of the other modes are much shorter and not responsible for the large later phase.

Eigenfunctions, that is, the spatial distributions of the water heights, and eigen periods of the first mode (a), fundamental mode, and second mode (b) computed from actual bathymetry for Hakodate Bay. The red ellipse shows the Hakodate port area which is the most populated and famous tourist area in Hakodate

Discussion and conclusions

This study shows that the later tsunami phases along the Pacific coast of the Hokkaido region, which were computed by solving the non-linear shallow water equations with a moving boundary condition, explain the observed tsunamis much better than those computed by solving the linear shallow water equations. This indicates that the later tsunami waves arrived at the tide gauge in Hakodate after propagating along the Pacific coast of the Tohoku region as edge waves with repeated inundations far inland or reflecting from the coast of Tohoku after the inundation. The spectral analysis of the waveform shows that the tsunami observed in Hakodate has a period of 45–50 min throughout the record after its arrival. This indicates that the tsunami waves that arrived at the mouth of Hakodate Bay excited the first mode of Hakodate Bay. The later tsunami waves mainly excited the first mode of the bay after propagating along the Pacific coast of the Tohoku region.

The eigenfunction of the first mode, that is, the spatial water height distribution, is the largest near the Hakodate port area, which is the most populated and famous tourist area in Hakodate. Large future tsunamis might excite the first mode of Hakodate Bay and cause large later phases near the Hakodate port. The residents and local disaster management office of Hakodate should be aware that there is a high possibility of large later tsunamis near the Hakodate port area when a tsunami warning is issued from the JMA. Citizens need to be evacuated from tsunami-affected areas for a much longer time than expected.

References

Borrero JC, Bell R, Csato C, DeLange W, Goring D, Greer SD et al (2013) Observations, effects and real time assessment of the March 11, 2011 Tohoku-oki tsunami in New Zealand. Pure Appl Geophys 170:1229–1248

Cheung KF, Bai Y, Yamazaki Y (2013) Surges around the Hawaiian islands from the 2011 Tohoku tsunami. J Geophys Res: Oceans 118:5703–5719. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrc.20413

Fujii Y, Satake K, Sakai S, Shinohara M, Kanazawa T (2011) Tsunami source of the 2011 off the Pacific coast of Tohoku earthquake. Earth Planets Space 63:55. https://doi.org/10.5047/eps.2011.06.010

Goto C, Ogawa Y, Shuto N, Imamura F (1997) Numerical method of tsunami simulation with the leap-flog scheme, IUGG/IOC TIME project, IOC manual and guides, vol 35, Paris, pp 1–126. https://www.jodc.go.jp/info/ioc_doc/Manual/122367eb.pdf

Gusman AR, Tanioka Y, Sakai S, Tsushima H (2012) Source model of the great 2011 Tohoku earthquake estimated from tsunami waveforms and crustal deformation data. Earth Planet Sci Lett 341:234–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2012.06.006

Horrillo J, Knight W, Kowalik Z (2008) Kuril Islands tsunami of November 2006: 2. Impact at Crescent City by local enhancement. J Geophys Res 113:C01021. https://doi.org/10.1029/2007JC004404

Imamura F (1996) Review of tsunami simulation with a finite difference method. In: Yeh H, Liu P, Synolakis C (eds) Long-Wave run-up models. World Scientific, Singapore, pp 231–241

Japan Meteorological Agency (2012) Report on the 2011 off the Pacific coast of Tohoku earthquake, Technical Report of the Japan Meteorological Agency, 133, 479 pp. (in Japanese)

Koshimura S, Hayashi Y, Munemoto K, Imamura F (2008) Effect of the emperor seamounts on trans-oceanic propagation of the 2006 Kuril Island earthquake tsunami. Geophys Res Let 35:L02611. https://doi.org/10.1029/2007GL032129

Kowalik Z, Horrillo J, Knight W, Logan T (2008) Kuril Islands tsunami of November 2006: 1. Impact at Crescent City by distant scattering. J Geophys Res 113:C01020. https://doi.org/10.1029/2007JC004402

Loomis H. G. (1975) Normal modes of oscillation of Honolulu harbor, Hawaii, Hawaii Inst. Geophys. Rep., HIG-75-20, 20 pp.

Mori N, Takahashi T (2012) The 2011 Tohoku earthquake tsunami joint survey group, 2012, Nationwide post event survey and analysis of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake tsunami. Coastal Eng J 54(1):1250001. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0578563412500015

Rabinovich AB, Thomson RE (2007) The 26 December 2004 Sumatra tsunami: analysis of tide gauge data from the world ocean part 1. Indian Ocean and South Africa. Pure Appl Geophys 164:261–308

Rabinovich AB, Thomson RE, Stephenson FE (2006) The Sumatra tsunami of 26 December 2004 as observed in the North Pacific and North Atlantic oceans. Surv Geophys 27:647–677. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10712-006-9000-9

Satake K, Fujii Y, Harada T, Namegaya Y (2013) Time and space distribution of coseismic slip of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake as inferred from tsunami waveform data. Bull Seis Soc Am 103(2B):1473–1492. https://doi.org/10.1785/0120120122

Satake K, Shimazaki K (1987) Computation of tsunami waveforms by a superposition of normal modes, J. Phys. Earth, 35:409–414.

Satake K, Shimazaki K (1988) Free oscillation of the Japan Sea excited by earthquakes – II. Model approach and synthetic tsunamis. Geophys J 93:457–463

Tanioka Y, Hasegawa Y, Kuwayama T (2008) Tsunami waveform analyses of the 2006 underthrust and 2007 outer-rise Kurile earthquakes. Adv Geosci 14:129–134

Tanioka Y, Katsumata K (2007) Tsunami generated by the 2004 Kushiro-oki earthquake. Earth Planets Space 59:e1–e3

Tappin DR, Grilli ST, Harris JC, Geller RJ, Masterlark T, Kirby JT, Shi F, Ma G, Thingbaijam KKS, Mai PM (2014) Did a submarine landslide contribute to the 2011 Tohoku tsunami? Marine Geology 357:344–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2014.09.043

Wu Y, Satake K (2018) Synthesis and source characteristics of tsunamis in the sea of Japan based on normal-mode method. J Geophys Res 123:5760–5773. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JB01570

Yamazaki Y, Cheung KF, Lay T (2018) A self-consistent fault slip model for the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. J Geophys Res SE 123:1435–1458. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017JB014749

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing. We thank two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments to improve the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan, under its Earthquake and Volcano Hazards Observation and Research Program.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article. Please contact author for data requests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YT proposed the topic, conceived and designed the study, and computed the normal mode. MS carried out the tsunami simulation and analyzed the computed data. YY helped the interpretation of the results. AG helped in the construction of the tsunami simulation program. KI helped in the installation of the tsunami simulation program and the interpretation of the result. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Tanioka, Y., Shibata, M., Yamanaka, Y. et al. Generation mechanism of large later phases of the 2011 Tohoku-oki tsunami causing damages in Hakodate, Hokkaido, Japan. Prog Earth Planet Sci 6, 30 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40645-019-0278-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40645-019-0278-x