Abstract

This paper provides a normative justification for the use of a minimum wage as a redistributive tool in a competitive labor market. We show that a government interested in improving the wellbeing of the deserving poor, while being less concerned with their undeserving counterparts, can use a minimum wage to enhance the efficiency of the tax-and-transfer system in attaining this goal.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

A minimum wage is used in many countries as a redistributive tool for the benefit of unskilled workers.Footnote 1 However, its normative justification is highly controversial due to its adverse effect on employment and the possibility of redistribution through the tax-and-transfer system.

Beginning with the seminal contribution of Mirrlees (1971), the major concern of the optimal income-tax literature has been with the government’s role in pursuing distributional goals in the presence of asymmetric information about workers’ characteristics. The canonical framework stipulates a competitive labor-market setting, which would lead to a Pareto-efficient allocation in the absence of government intervention. However, due to redistributive concerns and informational constraints, the government faces a non-trivial tradeoff between equity and efficiency. Hence, the government will generally choose an allocation that is not Pareto optimal, and the optimal income-tax literature primarily focuses on how expanding the set of policy tools available to the government beyond the tax-and-transfer system may improve this tradeoff.

One strand of this literature investigates whether a minimum wage could be such additional policy tool in a competitive labor-market environment. The focus is mainly on the intensive-margin setting where the choice is confined to working hours, and the key insight is that a minimum wage is in general not a desirable supplement to the tax-and-transfer system (Allen 1987; Guesnerie and Roberts 1987). A notable exception is Boadway and Cuff (2001) who demonstrate that if unemployment benefits are denied from workers who turn down wage offers exceeding the minimum wage, then a minimum wage can serve as a warranted supplement to an optimal tax-and-transfer system. The reason is that a minimum wage can then serve to distinguish between voluntarily (skilled) and involuntarily (unskilled) unemployed workers and thereby effectively target unemployment benefits to the latter. More recently, Danziger and Danziger (2015, 2018) show that a graduated (rather than a constant) minimum wage combined with an optimal tax-and-transfer system can be instrumental in achieving a Pareto improvement and study its welfare properties.Footnote 2

Lee and Saez (2012) instead focus on the extensive margin and examine the desirability of a minimum wage in an occupational-choice model with fixed working hours. They show that if rationing is efficient, namely, the involuntary unemployment triggered by a minimum wage will primarily hit the workers with the highest disutility of work, a minimum wage can be desirable.

The normative justification for a minimum wage in the occupational-choice extensive-margin model of Lee and Saez (2012) hinges on a restrictive assumption about the tax system. In particular, Lee and Saez consider an occupation tax which imposes a fixed levy on each occupation (high-skilled and low-skilled) independently of the earned income. If the production function exhibits perfect substitutability between skilled and unskilled labor inputs (i.e., a linear production function as in Saez 2002), this assumption would not be restrictive as the income level in each occupation would be given exogenously. An occupation tax would then be equivalent to an income tax. However, with complementarity between the various skill inputs, this assumption becomes restrictive as it rules out the tax being conditional on the endogenously determined income earned in each occupation. In particular, a more general income tax would allow, for each occupation, to set the tax liability for any income other than that realized in equilibrium. With an extensive-margin adjustment of labor, if the tax could be conditioned on income, a minimum wage could be fully replicated by a confiscatory 100% income tax on any income level below a minimal threshold coinciding with the realized income level in the low-skill sector in equilibrium. A minimum wage would then be redundant, as the allocation attained under the augmented income tax system would be equivalent to the one attained under the restrictive income tax system supplemented by a minimum wage.

The above literature assumes that the skill distribution is given. However, the tax-and-transfer system and the minimum wage may of course affect the human-capital formation and thereby the skill distribution. In a recent paper, Gerritsen and Jacobs (2016) consider an occupational choice model with competitive labor markets and endogenous human capital formation and address the question of whether income redistribution is more efficiently achieved through an increase in the minimum wage or through changes in the income tax. The threat of involuntary unemployment associated with an increase in the minimum wage may induce some low-skilled individuals to upgrade their skills to avoid unemployment. Provided that taxes rise with income, this results in revenue gains from increased high-skill employment offsetting the revenue losses from increased low-skill unemployment. Gerritsen and Jacobs show that for a minimum wage increase to dominate a distributional-equivalent tax change, revenue gains from higher skill formation should outweigh revenue losses from inefficient low-skilled labor rationing.Footnote 3

In this paper, we offer an alternative normative justification for the use of a minimum wage to supplement an optimal tax-and-transfer system. We consider the intensive-margin setting that captures the difference between wage and income and therefore provides a natural framework for examining the social desirability of a minimum wage as a supplement to the tax-and-transfer system.Footnote 4 Central to our argument is the distinction between the deserving and the undeserving poor, where deservedness refers to the society’s willingness to provide public support as reflected in the relative weights in the social welfare function. We capture this distinction by assuming that unskilled workers differ in their disutility from work, where those incurring a low disutility from work are referred to as deserving, while those incurring a high disutility from work are referred to as undeserving.

The association between incurring a high disutility from work and being perceived as undeserving can be interpreted in several manners. A high disutility from work may reflect laziness, so that society has some bias in favor of the poor workers who are more willing to work hard (long hours) relative to those poor workers who are less willing to do so. Incurring a high disutility from work may alternatively reflect family circumstances, such as being a teenager or a secondary earner of a household. In both cases, the worker is likely to have a higher reservation wage and typically opts for a part-time job. For instance, teenage workers are less constrained by long-term financial obligations (e.g., mortgages), have more attractive outside opportunities (e.g., schooling), and may receive their parents’ support; likewise, secondary earners may rely on their spouses’ income and therefore already enjoy a high level of consumption.

Of course, incurring a high disutility from work could well be associated with social circumstances such as disability and single parenthood that warrant public support. Individuals in these categories may to some extent be identified and targeted by specialized welfare programs that address their particular needs (e.g., Temporary Assistance to Needy Families and Social Security Disability Insurance). However, in many cases, distinguishing between more and less deserving within the pool of low-skilled workers exhibiting a high disutility from work may be a daunting challenge for the government. For instance, according to the US Census Bureau Data (see Weisbach 2009 and the references therein), among the top ten disabilities, back/spinal problems (excluding spinal cord injuries and paralysis) are by far the most prevalent. Another common source of claimed disability is mental problems (excluding retardation). However, both back pains and mental problems are difficult to verify compared with disabilities such as blindness, heart/artery problems, and diabetes which are readily verifiable.

Due to the problem of verification faced by the government, incurring a high-disutility from work is imperfectly correlated with welfare deservedness. That being said, our model assumes that the correlation is sufficiently large to warrant assigning a lower welfare weight to low-skilled workers with a high disutility from work.

In our model, the government maximizes a social welfare function that favors the deserving poor. However, as the disutility from work is unobservable, the government cannot directly identify the deserving poor and is faced with a screening problem. We demonstrate that a minimum wage can help the government overcome this challenge.

When working hours are rationed in a manner which is sufficiently close to being constrained efficient (precisely defined below in the formal model) in the sense that most of the involuntary underemployment triggered by the imposition of a minimum wage falls on the undeserving poor, extra transfers offered by the government to unskilled workers can be targeted toward the deserving poor rather than being accorded to all poor across the board.Footnote 5 We demonstrate that by relying on the screening of workers through the rationing of working hours, the government may overcome its inability to identify the deserving poor directly. Consequently, a minimum wage may become a desirable supplement to an optimal tax-and-transfer system.Footnote 6

The notion of welfare deservedness has attracted much attention in recent years and has become a key issue in the public discourse about the role of the welfare system. Abundant evidence shows that society is generally sympathetic toward supporting the poor but that generosity is often conditioned on the recipients either working hard or being disabled. For instance, Gilens (1999) reports that people are more concerned about the conditions determining which recipients should benefit from social security programs than about the cost of the programs, the main question for taxpayers being not so much “who gets what?” but rather “who deserves what?”. In other words, it is not the government support for the truly needy that sparks considerable public resentment, but rather the perception that many individuals receiving welfare are undeserving.Footnote 7 These trends are reflected in the 1996 welfare reform in the USA and the shift from the Aid to Families with Dependent Children program to the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program with its emphasis on the work requirement, as well as the significant expansion in recent years of the Earned Income Tax Credit program that conditions welfare on labor market participation.

Several previous studies have distinguished between the deserving and undeserving poor in order to provide a normative foundation for commonly used policy tools such as the Earned Income Tax Credit program and Workfare to target benefits to the deserving poor. For instance, Besley and Coate (1992, 1995) assume that the government objective is to alleviate poverty rather than to maximize social welfare. Effectively, this eliminates disutility from work from the government objective and may be interpreted to reflect the view that high disutility from work indicates a socially unacceptable trait. They show that workfare can then be an effective screening tool that supplements means testing. Relatedly, Kanbur et al. (1994) establish the case for levying a negative marginal tax rate on the working poor when the government aims to minimize an income-based poverty index. Cuff (2000) employs a framework where individuals differ along the skill dimension and in their disutility from work. She demonstrates that work requirements can be desirable if the government objective is to maximize the well-being of the unskilled workers incurring a low disutility from work (the deserving poor). Saez (2002) discusses the possibility of assigning a relatively low marginal social weight to unemployed unskilled workers and shows that this would reinforce the case for an Earned Income Tax Credit. Finally, Blumkin et al. (2015) demonstrate that statistical stigma can be an effective welfare ordeal mechanism to sort out those claimants considered undeserving.

2 The model

We consider a simple setup with just the key ingredients necessary to demonstrate our point. The economy is comprised of skilled and unskilled workers that produce a single consumption good the price of which is unity. The mass of each skill group is unity. The output X is given by

where Nu and Ns denote the total working hours of the unskilled and skilled workers, respectively. The function F is increasing has constant returns to scale, and exhibits diminishing marginal productivity in the input of each skill level.Footnote 8

Let c denote consumption, n working hours, and g(n) the disutility of work, where g(0) = 0, g′ > 0, g′′ > 0 and \( \underset{n\to 0}{\lim }{g}^{\prime }(n)=0 \). The utility of the skilled workers (indexed by superscript s) is given by us ≡ cs − g(ns). Unskilled workers differ in their disutility from work. For a fraction α ∈ (0, 1) of the unskilled workers (indexed by superscript d) the utility is given by ud ≡ cd − g(nd). For the remaining fraction 1 − α of the unskilled workers (indexed by superscript l), the utility is given by ul ≡ cl − kg(nl), where k > 1. That is, type-l unskilled workers incur a higher disutility (both total and marginal) from work relative to their type-d unskilled counterparts for the same working hours supplied. We will henceforth refer to type-d workers as deserving poor and to type-l workers as undeserving poor. That is, we interpret the choice to work fewer hours in the labor market (stemming from the higher disutility from work) as reflecting a socially undesirable trait.

The total labor supply of the skilled workers is given by Ns = ns, and the total labor supply of the unskilled workers by Nu = αnd + (1 − α)nl. Assuming a competitive labor market, each worker is paid the value of his marginal product. Therefore, ws ≡ ∂F(Nu, Ns)/∂Ns is the wage of skilled workers and wu ≡ ∂F(Nu, Ns)/∂Nu is the wage of unskilled workers. We assume that ws > wu.

The government’s social welfare is given by a weighted average of the utilities,

where ∑iβi = 1 and i = s, d, l. We assume that the social welfare weight assigned to type-s workers is less than their fraction in the population, i.e., 0 ≤ βs < 1/2. This represents society’s egalitarian preferences and is fairly standard.Footnote 9 We also assume that the social welfare weight assigned to type-l workers is lower than their fraction in the population, i.e., 0 ≤ βl < (1 − α)/2. This reflects the public’s perception that individuals whose preferences induce them to work relatively fewer hours are less deserving of government support (see our elaborate discussion in the introduction).Footnote 10

3 The benchmark regime: no minimum wage

We start by analyzing the benchmark case with no minimum wage so that a non-linear tax-and-transfer system is the only available redistributive policy tool. The government maximizes the social welfare given in (2) by choosing a triplet of consumption-work bundles (ci, ni), i = s, d, l, satisfying the revenue constraint

and the six incentive-compatibility constraints denoted by ICij, i, j = s, d, l where i ≠ j, which express that a worker of type i has no incentive to mimic a worker of type j, i.e., that

where ks = kd = 1, kl = k and wd = wl = wu.

The following lemma summarizes important properties of the optimal solution.Footnote 11

Lemma: In a social welfare optimum without a minimum wage:

-

(i)

IC sd and IC ld are the only binding incentive-compatibility constraints;

-

(ii)

nd > nl.

Proof: See Appendix A.

Part (i) of the lemma states that the downward incentive-compatibility constraint ICsd is binding. This accords with the standard optimal-tax model where the direction of redistribution goes from the high to the low earners. The fact that the downward incentive-compatibility constraint ICsd binds implies that the skilled workers are indifferent between choosing their intended bundle and mimicking the deserving unskilled workers. Part (i) of the lemma also states that the upward incentive-compatibility constraint ICld is binding even though, as shown by part (ii) of the lemma, the undeserving poor work less and hence earn less than the deserving poor. This feature derives from the government’s lower valuation of the undeserving poor and implies that the latter are indifferent between choosing their intended bundle and working more in order to mimic their deserving counterparts.

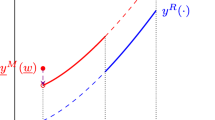

Figure 1 illustrates the government optimal solution under the benchmark regime in the income-consumption space. The three upward-sloping curves, denoted by us, ud, and ul, represent the indifference curves associated with the skilled, deserving unskilled, and undeserving unskilled workers, respectively. Notice that the single-crossing property holds, namely, the indifference curve of the undeserving unskilled is steeper than that of the deserving unskilled, which in turn is steeper than that of the skilled. The equilibrium income-consumption bundles associated with the skilled, deserving unskilled, and undeserving unskilled workers are given by E, F, and G, correspondingly. As stated in part (i) of the lemma, the incentive-compatibility constraint ICsd, associated the skilled workers, and the incentive-compatibility constraint, ICld, associated with the undeserving unskilled workers, are binding. That is, the bundles E and F lie on the same indifference curve, us, associated with the skilled workers, whereas the bundles F and G lie on the same indifference curve, ul, associated with the undeserving unskilled workers. As both types of unskilled workers earn the same wage, the fact that the income level associated with bundle F exceeds that associated with bundle G indicates that the deserving unskilled workers work more hours than their undeserving counterparts, as stated in part (ii) of the lemma.

4 The welfare-enhancing role of a minimum wage

A binding minimum wage sets a lower bound for the wage that can be paid to the unskilled workers and thus effectively determines a binding upper bound for their working hours. The ensuing excess supply of unskilled workers necessitates some form of rationing. Rationing rules may be characterized by the extent to which they are efficient. Rationing is defined as efficient when the total hours of work are shared in a manner that maximizes the aggregate surplus of the workers whose workload is being allocated (put differently, the allocation of a given number of working hours minimizes the total disutility of labor).

We focus on a rationing rule which is constrained efficient in the sense that the working hours of the unskilled labor are allocated so as to maximize the aggregate surplus of the unskilled workers given the tax-and-transfer system in place. In our context, as will be formally shown in Appendix B (Part I), constrained efficient rationing entails that the entire incidence of the involuntary underemployment falls on the undeserving poor (as they derive the least surplus from working).Footnote 12

With random rationing, all the unskilled workers would be equally likely to be employed less than they desire. Realistically, rationing would lie somewhere in between these two extremes and we will focus on the case where the rationing is sufficiently close to being constrained efficient, henceforth called nearly constrained efficient, in that a sufficiently large share of the incidence of involuntary underemployment falls on the undeserving poor.Footnote 13 As we will show, in such a case, supplementing an optimal tax-and-transfer system with a binding minimum wage can enhance welfare:

Proposition: If rationing of employment hours is nearly constrained efficient , supplementing an optimal tax-and-transfer system with a binding minimum wage enhances welfare.

Proof: See Appendix B.

5 Discussion

The rationale for the desirability of the minimum wage is as follows. Part (i) of the lemma shows that in the absence of a minimum wage, the incentive-compatibility constraint ICld associated with the undeserving poor would be binding. This limits the government’s redistributive capacity as increasing the transfer to the deserving poor would induce the undeserving poor to mimic their deserving counterparts, thereby violating ICld. However, with constrained efficient rationing (and the case of nearly constrained efficient rationing follows by continuity considerations) a minimum wage would block this undesirable supply-side response, causing the entire incidence of the induced involuntary underemployment to fall on the undeserving poor. Namely, the undeserving poor will be forced to work less than they would prefer given the tax-and-transfer schedule. With the mimicking possibilities of the undeserving poor being blocked, the government is able to offer more generous transfers to the deserving poor. Effectively, the minimum wage plays a screening role that ensures that the extra transfers are targeted to those deserving, rather than being accorded to all unskilled workers.

Figure 2 illustrates the proposition in the income-consumption space. The solid indifference curves represent the benchmark equilibrium in the absence of a minimum wage, as depicted in Fig. 1, whereas the dashed indifference curves represent the equilibrium in the presence of a minimum wage. The bundles E’, F’, and G’ reflect a revenue-neutral perturbation to the benchmark allocation given by the bundles E, F, and G. Under the perturbed regime, working hours and hence income levels remain unchanged. The consumption levels associated with the skilled and the deserving unskilled workers are increased in a manner that maintains the skilled workers’ incentive-compatibility constraint, ICsd, binding. Namely, the bundles E’ and F’ lie on the same dashed indifference curve associated with the skilled workers. The consumption level associated with the undeserving unskilled workers is decreased to maintain the government’s budget balanced. The latter violates the undeserving unskilled workers’ incentive-compatibility constraint, ICld. These now prefer to mimic their deserving unskilled counterparts. Namely, the bundle F’ lies above the dashed indifference curve going through the bundle G’. Mimicking, however, is rendered infeasible by the binding minimum wage due to the constrained efficient rationing that prevents the undeserving unskilled workers from working longer hours to replicate the deserving unskilled workers’ income.

It is important to clarify the rationale underlying the difference between our finding that a minimum wage is desirable and the earlier negative result in Allen (1987) and Guesnerie and Roberts (1987) that a minimum wage cannot be a useful supplement to an optimal tax-and-transfer system. In these two studies, the government’s redistributive policy is constrained by the skilled workers’ binding downward incentive-compatibility constraint, which makes them indifferent between whether or not to mimic the unskilled workers. In such a case, imposing a minimum wage is useless since it does not make mimicking harder for the skilled workers. In contrast, in our setting, the government’s redistributive policy is constrained by the undeserving poor’s binding upward incentive-compatibility constraint, which makes them indifferent between whether or not to mimic the deserving poor. As the undeserving poor would have to increase their working hours in order to mimic the deserving poor, an effective upper bound on the undeserving poor’s working hours is desirable. This is achieved by the minimum wage, which sets an upper bound on the working hours of all unskilled workers. With constrained efficient rationing of employment hours, the latter is translated into an upper bound on only the working hours of the undeserving poor.Footnote 14

A minimum wage is clearly not the only policy tool that could serve to screen between the deserving and undeserving poor. Two notable policy tools that could serve the same purpose are wage subsidies (e.g., the Earned Income Tax Credit in the USA) and work/training requirements for welfare eligibility (Workfare). Both of these widely used policy tools would induce an increase in the labor supply of the deserving poor, rendering it less attractive for the undeserving poor to mimic their deserving counterparts, thereby enhancing the screening efficiency of the tax-and-transfer system. Indeed, in a working paper version (Blumkin and Danziger 2014), we have examined the desirability of levying a negative marginal tax rate on the deserving poor. We first show that in the absence of a minimum wage, a negative marginal tax rate may be optimal. We then demonstrate that by supplementing the tax-and-transfer system with a binding minimum wage, assuming that employment hours are efficiently rationed, the undeserving poor cannot mimic the deserving poor. This would, therefore, obviate the need to distort the labor supply of the deserving poor upward in order to mitigate the mimicking incentive of the undeserving poor. Thus, the minimum wage is more efficient than a negative marginal tax rate in targeting benefits to the deserving poor. While a formal analysis of workfare is beyond the scope of this paper, a minimum wage appears to have similar efficiency advantages over a workfare program, which entails labor supply distortions resembling those associated with a negative marginal tax rate.

6 Conclusion

In this paper, we offer a normative justification for the use of a minimum wage to promote redistributive goals in a competitive labor market. Motivated by the ample empirical evidence showing that the general public is reluctant to support those poor perceived to be undeserving, we assume that unskilled workers differ in their disutility of work and further postulate that the unskilled workers with high disutility from work are those considered to be less deserving of receiving government support. This is reflected in their relatively low weight in the social welfare function. We demonstrate that a minimum wage is a desirable supplement to an optimal tax-and-transfer system when the rationing of employment hours is nearly constrained efficient. The reason is that a minimum wage can be used as a screening device to distinguish between deserving and undeserving poor and thereby to enhance the government capacity to direct transfers toward those considered more deserving of support.

Notes

See Neumark and Wascher (2007) for a survey of the minimum wage. The federal minimum wage in the USA has been $7.25 per hour since July 2009 (reflecting an increase of 40% over the years 2007–2009). Some states and cities have set minimum wages exceeding the federal level, for instance, $11.5 per hour in the state of Washington and $11.00 per hour in California and Massachusetts; in San Francisco, the minimum wage is $15.00 per hour, and in New York City, the minimum wage for large employers is expected to be $15.00 per hour by the end of 2018.

A different strand of the literature considers the efficiency-enhancing role of a minimum wage in the presence of labor market imperfections; see Lee and Saez (2012) for a short review of this literature.

The implications of inefficient rationing for optimal tax systems are discussed in Gerritsen (2016).

The voluminous empirical literature on the labor-market impact of a minimum wage has primarily focused on the extensive margin. However, a few papers have also studied the impact of a minimum wage on the intensive margin. Among them, Zavodny (2000) and Doppelt (2017) find a positive relationship between the minimum wage and working hours; Connolly and Gregory (2002) and Allegretto et al. (2011) find no significant relationship, whereas Couch and Wittenburg (2001) and Stewart and Swaffield (2008) find a negative relationship (which is hard to reconcile with a competitive labor market). Possible reasons for the mixed empirical results include the presence of imperfect competition in the labor market for low-skill workers and compliance issues.

The empirical evidence on efficient rationing is scarce. Some supporting evidence, however, may be found in Luttmer (2007) and Neumark and Wascher (2007). Thus, Luttmer (2007) shows that an increase in the minimum wage does not cause workers with higher reservation wages to displace equally skilled workers with lower reservation wages. The workers who value their job the least are those who tend to lose their jobs due to a minimum wage increase. Neumark and Wascher (2007) further show that the employment effect of a minimum wage is strongest among those who are likely to have the highest reservation wage and typically opt for part-time jobs (such as teenagers and secondary earners). Testing the efficiency hypothesis is beyond the scope of the current paper and calls for future research.

The traditional assumption in the optimal-taxation literature is that the government is unable to observe wages and therefore conditions transfers and taxes on observable income levels. This informational assumption may appear inconsistent with the common practice of simultaneously imposing an income tax and a minimum wage. However, we follow the reasoning in Lee and Saez (2012) who argue that this simultaneous use can be enforced by a combination of whistle blowing by underpaid workers and ex-post costly verification of wages by the government.

See also Heclo (1986), Farkas and Robinson (1996), Gallop Organization (1998), Miller (1999), and Fong (2001). According to one poll cited in Gilens (1999), 74% of the public agrees that the criteria for welfare are not strong enough but only 3% reports that they would oppose a 1% sales tax increase aimed at funding help to the poor.

The combination of constant returns to scale and diminishing marginal productivity in the input of each skill level implies that the two types of labor are complementary in production. If, instead, the production function were linear in the two inputs, then a binding minimum wage would crowd out all unskilled workers from the labor market. Consequently, a binding minimum wage would not be a desirable supplement to an optimal tax-and-transfer system as such crowding-out could be achieved by the tax-and-transfer system alone. For empirical evidence supporting our assumption of complementarity between the unskilled and skilled workers in the production function, see Hamermesh (1996).

The maximization of a weighted sum of the individuals’ utilities characterizes the second-best Pareto-efficient frontier. To set focus on the interesting case in which the direction of redistribution goes from the skilled workers toward their unskilled counterparts, we assume that the Pareto weight assigned to the skilled workers is strictly lower than their share in the population.

Our approach is in line with that in Cuff (2000) who invokes a Rawlsian welfare function and considers the case in which a high disutility from work reflects a form of laziness. Hence, the individuals whose utility is being maximized are those with low ability and low disutility from work. In our framework this would correspond to setting βs = βl = 0.

We assume that the optimal solution is separating so that each type of unskilled worker receives a distinct consumption-work bundle. This will be the case when the welfare weight assigned to type-l workers is sufficiently low.

In the laissez-faire equilibrium with a minimum wage but in the absence of a tax-and-transfer system, efficient rationing would entail that both types of unskilled workers (deserving and undeserving) would share the burden of underemployment, so as to equalize their marginal disutility of labor. Constrained by the tax-and-transfer system, working hours cannot be allocated in a manner that equalizes the marginal disutility of labor. Instead, in our context, we obtain a corner solution where the entire burden of underemployment is borne by the undeserving unskilled workers.

Formally, we consider an extension of the constrained efficient rationing rule by introducing a noise component which implies that the probability of becoming involuntarily underemployed becomes positive for both the deserving and undeserving poor. We then consider the limiting case in which the magnitude of the noise component goes to zero.

Allen (1987) already mentions that a minimum wage can be a useful policy tool when the incentive- compatibility constraint is upward binding. This would be irrelevant in Allen’s two-type setting with a standard welfare function, since it would require that the redistribution goes from the poor toward the rich. In our case with a three-type framework, redistribution goes from the undeserving poor (who earn less) toward their deserving counterparts (who earn more).

References

Allegretto S, Dube A, Reich M (2011) Do minimum wages really reduce teen employment? Accounting for heterogeneity and selectivity in state panel data. Ind Relat 50:205–240

Allen S (1987) Taxes, redistribution, and the minimum wage: a theoretical analysis. Q J Econ 102:477–490

Besley T, Coate S (1992) Workfare versus welfare incentive-compatibility arguments for work requirements in poverty-alleviation programs. Am Econ Rev 82:249–261

Besley, T. and Coate, S. (1995) “The Design of Income Maintenance Programs,” Review of Economic Studies, 62:187–221.

Blumkin, T., and Danziger, L. (2014) “Deserving poor and the desirability of a minimum wage,” IZA Discussion Paper No 8418

Blumkin T, Margalioth Y, Sadka E (2015) Welfare Stigma Re-examined. J Public Econ Theory 17:874–886

Boadway R, Cuff K (2001) A minimum wage can be welfare-improving and employment-enhancing. Eur Econ Rev 45:553–576

Connolly S, Gregory M (2002) The national minimum wage and hours of work: implications for low paid women. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 64:607–631

Couch, K. and Wittenburg, D. (2001) “The response of hours of work to increases in the minimum wage,” South Econ J 68:171–177

Cuff K (2000) Optimality of workfare with heterogeneous preferences. Can J Econ 33:149–174

Danziger E, Danziger L (2015) A Pareto-improving minimum wage. Economica 82:236–252

Danziger, E. and Danziger, L. (2018) “The Optimal Graduated Minimum Wage and Social Welfare,” Res Labor Econ 46:55–72

Doppelt, R. (2017) “Minimum wages and hours of work,” Mimeo, Penn State University, PA, USA

Farkas S, Robinson J (1996) The values we live by: what Americans want from welfare reform. Public Agenda, New York

Fong C (2001) Social preferences, self-interest, and the demand for redistribution. J Public Econ 82:225–246

Gallop Organization (1998) “Haves and have-nots: perceptions of fairness and opportunity”

Gerritsen, A. (2016) “Equity and efficiency in rationed labor markets”, Working Paper No. 2016–4, Munich: Max Planck Institute for Tax Law and Public Finance

Gerritsen, A. and Jacobs, B. (2016) “Is a minimum wage an appropriate instrument for redistribution?”

Gilens, M. (1999) “Why Americans hate welfare,” University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Guesnerie R, Roberts K (1987) Minimum wage legislation as a second best policy. Eur Econ Rev 31:490–498

Hamermesh DS (1996) Labor demand. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Heclo, H. (1986) “The Political Foundations of Antipoverty Policy,” in S. Danziger and D. Weinberg (eds.) Fighting Poverty: What Works and What Doesn’t, Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Kanbur R, Keen M, Tuomala M (1994) Optimal non-linear income taxation for the alleviation of poverty. Eur Econ Rev 38:1613–1632

Lee D, Saez E (2012) Optimal minimum wage policy in competitive labor markets. J Public Econ 96:739–749

Luttmer E (2007) Does the minimum wage cause inefficient rationing? The B.E Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy 7 (Contributions), Article 49, 1–40

Miller D (1999) Principles of social justice. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Mirrlees J (1971) An exploration in the theory of optimum income taxation. Rev Econ Stud 38:175–208

Neumark D, Wascher W (2007) Minimum wages and employment. Found Trends Microeconomics 3:1–182

Saez E (2002) Optimal income transfer programs: intensive versus extensive labor supply responses. Q J Econ 117:1039–1073

Stewart M, Swaffield J (2008) The other margin: do minimum wages cause working hours adjustments for low-wage workers? Economica 75:148–167

Weisbach D (2009) Toward a new approach to disability law. University of Chicago Legal Forum 1:47–102

Zavodny M (2000) The effect of the minimum wage on employment and hours. Labour Econ 7:729–750

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the referees and the editor for their insightful comments and constructive suggestions. We also thank Spencer Bastani, Sören Blomquist, Luca Micheletto, Casey Rothschild, Laurent Simula, and participants in the UCFS Public Economics Seminar in Uppsala University, the CESifo Employment and Social Protection Area Conference in Munich, the European Economic Association Conference in Mannheim, and the Taxation Theory Conference in Cologne for helpful comments and suggestions.

Responsible editor: Pierre Cahuc

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The IZA Journal of Labor Economics is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The authors declare that they have observed these principles.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A

1.1 Proof of Lemma

Part (i) The only binding incentive constraints are ICsd and ICld.

Proof: We prove this part by a series of claims.

Claim 1: ICsl is slack.

Proof: By virtue of ICsd it follows that

(A1) \( {c}^s-g\left({n}^s\right)\ge {c}^d-g\left(\frac{n^d{w}^u}{w^s}\right). \)

Suppose, by way of contradiction, that ICsl is binding, hence:

(A2) \( {c}^s-g\left({n}^s\right)={c}^l-g\left(\frac{n^l{w}^u}{w^s}\right) \).

Subtracting (A2) from (A1) implies that

(A3) \( {c}^l-g\left(\frac{n^l{w}^u}{w^s}\right)\ge {c}^d-g\left(\frac{n^d{w}^u}{w^s}\right) \).

By virtue of ICdl it follows that

(A4) cd − g(nd) ≥ cl − g(nl).

Subtracting (A4) from (A3) yields:

(A5) \( g\left({n}^l\right)-g\left(\frac{n^l{w}^u}{w^s}\right)\ge g\left({n}^d\right)-g\left(\frac{n^d{w}^u}{w^s}\right) \).

where \( H(n)\equiv g(n)-g\left(\frac{n{w}^u}{w^s}\right) \). Differentiation of H(n) with respect to n yields.

(A6) \( {H}^{\prime }(n)={g}^{\prime }(n)-{g}^{\prime}\left(\frac{n{w}^u}{w^s}\right)\frac{w^u}{w^s}>0 \),

where the inequality follows from the strict convexity of g and the fact that ws > wu. It follows from (A5) that nl ≥ nd. By our presumption of a separating equilibrium it follows that nl > nd.

By virtue of ICld it follows that

(A7) cl − kg(nl) ≥ cd − kg(nd).

Subtracting (A7) from (A4) implies:

(A8) (k − 1)[g(nd) − g(nl)] ≥ 0.

As k > 1 and g is increasing, it follows that nd ≥ nl. We therefore obtain a contradiction. Thus, ICsl is slack.

Claim 2: ICsd is binding.

Proof: Suppose, by way of contradiction, that ICsd is slack and consider the following small perturbation to the presumed optimal solution:

\( {\overset{\sim }{\mathrm{c}}}^s={\mathrm{c}}^s-\upvarepsilon \), \( {\overset{\sim }{\mathrm{c}}}^d={\mathrm{c}}^d+\upvarepsilon \) and \( {\overset{\sim }{\mathrm{c}}}^l={\mathrm{c}}^l+\upvarepsilon \), where ε > 0.

By continuity considerations, ICsd and ICsl are maintained (the former is slack by presumption and the latter is slack by claim 1). Moreover, by construction of the perturbation, neither the revenue constraint nor any of the other incentive-compatibility constraints is violated. The suggested perturbation yields an increase in social welfare, as by presumption βs < 1/2; hence, the total change in welfare is given by ΔW = ε(1 − 2βs) > 0. We thus obtain the desired contradiction.

Claim 3: ICls is slack.

Proof: Suppose, by way of contradiction, that ICls is binding. Thus,

(A9) \( {c}^l- kg\left({n}^l\right)={c}^s- kg\left(\frac{n^s{w}^s}{w^u}\right). \)

By virtue of ICld it follows that

(A10) cl − kg(nl) ≥ cd − kg(nd).

Substituting (A9) into (A10) yields

(A11) \( {c}^s- kg\left(\frac{n^s{w}^s}{w^u}\right)\ge {c}^d- kg\left({n}^d\right). \)

By virtue of ICds it follows that

(A12) \( {c}^d-g\left({n}^d\right)\ge {c}^s-g\left(\frac{n^s{w}^s}{w^u}\right) \).

After rearrangement, (A11) and (A12) yield

(A13) \( \left(k-1\right)\left[g\left(\frac{n^s{w}^s}{w^u}\right)-g\left({n}^d\right)\right]\le 0 \).

As k > 1 and g is increasing, (A13) implies that nsws/wu ≤ nd. By the assumption that the equilibrium is separating it follows that

(A14) \( \frac{n^s{w}^s}{w^u}<{n}^d \).

By virtue of claim 2 ICsd is binding, hence, it follows that

(A15) \( {c}^s-g\left({n}^s\right)={c}^d-g\left(\frac{n^d{w}^u}{w^s}\right) \).

After rearrangement, (A15) and (A12) yield

(A16) \( g\left(\frac{n^s{w}^s}{w^u}\right)-g\left({n}^s\right)\ge g\left({\mathrm{n}}^d\right)-g\left(\frac{n^d{w}^u}{w^s}\right) \)

where \( H(n)\equiv g(n)-g\left(\frac{n{w}^u}{w^s}\right) \). Differentiation of H(n) with respect to n yields.

(A17) \( {H}^{\prime }(n)={g}^{\prime }(n)-{g}^{\prime}\left(\frac{n{w}^u}{w^s}\right)\frac{w^u}{w^s}>0 \),

where the inequality follows from the strict convexity of g and the fact that ws > wu. It follows from (A17) that nsws/wu ≥ nd, which violates (A14). Thus, ICls is slack.

Claim 4: ICld is binding.

Proof: Suppose, by way of contradiction, that ICld holds as a strict inequality. Consider the following small perturbation to the presumed optimal solution:

\( {\overset{\sim }{\mathrm{c}}}^s={\mathrm{c}}^s+\upvarepsilon \), \( {\overset{\sim }{\mathrm{c}}}^d={\mathrm{c}}^d+\upvarepsilon \) and \( {\overset{\sim }{\mathrm{c}}}^l={\mathrm{c}}^l-\updelta \), where ε, δ > 0 and (1 − α)δ = (1 + α)ε.

By continuity considerations ICld and ICls are maintained (the former is slack by our presumption and the latter by virtue of claim 3). Moreover, by construction of the perturbation neither the revenue constraint nor any of the other incentive-compatibility constraints is violated. The suggested perturbation yields an increase in social welfare, as by presumption βl < (1 − α)/2; hence, the total change in welfare is given by \( \Delta W=\varepsilon \left(1-{\beta}^l\right)-\updelta {\beta}^l=\varepsilon \left[1-\frac{2{\beta}^l}{\left(1-\alpha \right)}\right]>0 \). We thus obtain the desired contradiction.

Claim 5: ICdl is slack.

Proof: Suppose by negation that IChl is binding. Thus,

(A18) cd − g(nd) = cl − g(nl).

By virtue of claim 4 IClh is binding; hence

(A19) cl − kg(nl) = cd − kg(nd).

Subtracting (A19) from (A18) yields upon rearrangement

(A20) (k − 1)[g(nd) − g(nd)] = 0.

As g(n) is increasing and k > 1, it follows that nd = nl. By the assumption of a separating equilibrium, we obtain the desired contradiction.

Claim 6: ICds is slack.

Proof: Suppose by negation that IChs is binding. Hence,

(A21) \( {c}^d-g\left({n}^d\right)={c}^s-g\left(\frac{n^s{w}^s}{w^u}\right) \).

By virtue of claim 2 ICsd is binding. Hence,

(A22) \( {c}^s-g\left({n}^s\right)={c}^h-g\left(\frac{n^d{w}^u}{w^s}\right) \).

Subtracting (A22) from (A21) yields:

(A23) \( g\left(\frac{n^s{w}^s}{w^u}\right)-g\left({n}^s\right)=g\left({n}^d\right)-g\left(\frac{n^d{w}^u}{w^s}\right) \)

where \( H(n)\equiv g(n)-g\left(\frac{n{w}^u}{w^s}\right) \). Differentiation of H(n) with respect to n yields.

(A24) \( {H}^{\prime }(n)={g}^{\prime }(n)-{g}^{\prime}\left(\frac{n{w}^u}{w^s}\right)\frac{w^u}{w^s}>0 \),

where the inequality follows from the strict convexity of g and the fact that ws > wu. It follows from (A24) that \( \frac{n^s{w}^s}{w^u}={n}^h \). We thus obtain a contradiction by our presumption of a separating equilibrium.

Part (ii): nh > nl.

Proof: By virtue of claim 5, IChl is slack, hence:

(A25) cd − g(nd) > cl − g(nl).

By virtue of part claim 4 the constraint IClh is binding; hence

(A26) cl − kg(nl) = cd − kg(nd).

Subtracting (A26) from (A25) yields upon rearrangement

(A27) (k − 1)[g(nd) − g(nl)] > 0.

As g(n) is increasing and k > 1, it follows that nd > nl. This completes the proof.

Appendix B

1.1 Proof of Proposition

Suppose that there is no minimum wage in place and let the triplet (\( {c}_{\ast}^i,{n}_{\ast}^i\Big), \) where i = s, d, l, denote the optimal tax-and-transfer schedule that maximizes the welfare expression in (2) subject to the revenue constraint (3) and the incentive-compatibility constraints (4). The construction of the proof will be as follows. We will consider a small revenue-neutral perturbation to the optimal tax-and-transfer system. We will show that by imposing a binding minimum wage and further assuming that rationing is constrained efficient (as formally defined below) the suggested perturbation will violate none of the incentive-compatibility constraints (Part I). We will then demonstrate that the suggested perturbation results in a welfare gain (Part II). Finally, we will consider an extension to a more general class of rationing rules and demonstrate that the key result continues to hold when rationing is nearly constrained efficient (Part III).

I. A small revenue-neutral perturbation

Consider the following small perturbation to the optimal solution (characterized in Appendix A):

\( {\overset{\sim }{\mathrm{c}}}^s={\mathrm{c}}_{\ast}^s+\upvarepsilon \), \( {\overset{\sim }{\mathrm{c}}}^d={\mathrm{c}}_{\ast}^d+\upvarepsilon \) and \( {\overset{\sim }{\mathrm{c}}}^l={\mathrm{c}}_{\ast}^l-\updelta \), where ε, δ > 0 and (1 − α)δ = (1 + α)ε.

Notice that, by construction, provided that the resulting allocation is incentive compatible (as will be verified below), the suggested perturbation is revenue neutral.

In addition, suppose that the government sets a minimum wage at the level of the equilibrium unskilled wage under an optimal income tax-and-transfer schedule in the absence of a minimum wage. Formally, let \( \overline{w}=\partial F\left({\alpha n}_{\ast}^d+\left(1-\alpha \right){n}_{\ast}^l,{n}_{\ast}^s\right)/\partial {N}^u \) denote the minimum wage.

We turn next to verify that none of the incentive-compatibility constraints are violated. By construction of the suggested perturbation and by virtue of the quasi-linear utility specification, the incentive-compatibility constraints ICsd and ICds remain unchanged, whereas the incentive-compatibility constraints ICsl and ICdl are mitigated. Furthermore, by virtue of part (i) of the lemma, ICls is slack and hence remains satisfied under the suggested perturbation by continuity considerations. On the other hand, ICld, which by virtue of part (i) of the lemma is binding under an optimal tax-and-transfer regime, is violated by the suggested perturbation, since the undeserving poor would prefer the bundle associated with their deserving counterparts to their own bundle. However, we will now demonstrate that the binding minimum wage blocks such mimicking.

By virtue of the incentive-compatibility constraints ICdl and ICld, the introduction of a binding minimum wage results in involuntary underemployment/unemployment. To see this, notice that the deserving and undeserving poor are willing to work \( {n}_{\ast}^d \) hours since both types strictly prefer the bundle \( \left({\overset{\sim }{\mathrm{c}}}^d,{n}_{\ast}^d\right) \) to any other available bundle. This implies that the total labor supply of the unskilled workers is given by \( {n}_{\ast}^d \). However, the total labor demand for the low-skilled workers is given by \( {\alpha n}_{\ast}^d+\left(1-\alpha \right){n}_{\ast}^l<{n}_{\ast}^d \), where the inequality sign follows from part (ii) of the lemma.

Some form of rationing is required due to the gap between the demand and supply of labor. We will henceforth assume that rationing is constrained efficient, namely, the working hours demanded by the firms, given the tax-and-transfer system in place, are allocated so as to maximize the aggregate surplus of the unskilled workers. As will be shown below, constrained efficient rationing implies that the entire incidence of underemployment will fall on the undeserving poor. That is, the undeserving poor will become underemployed and only work \( {n}_{\ast}^l \) hours, whereas, the deserving poor will continue to work \( {n}_{\ast}^d \) hours. Formally, constrained efficient rationing implies that the allocation of working hours maximizes the aggregate surplus of the unskilled workers:

(B1) \( S\equiv \left({x}^d+{x}^l\right){\overset{\sim }{\mathrm{c}}}^l+\left({z}^d+{z}^l-{x}^d-{x}^l\right){\overset{\sim }{\mathrm{c}}}^d-\left({z}^d-{x}^d\right)g\left({n}_{\ast}^d\right)-{x}^dg\left({n}_{\ast}^l\right)-\left({z}^l-{x}^l\right) kg\left({n}_{\ast}^d\right)-{x}^l kg\left({n}_{\ast}^l\right) \)subject to the constraint

(B2) \( \left({z}^d+{z}^l-{x}^d-{x}^l\right){n}_{\ast}^d+\left({x}^d+{x}^l\right){n}_{\ast}^l={\alpha n}_{\ast}^d+\left(1-\alpha \right){n}_{\ast}^l \),

where 0 ≤ xd ≤ zd ≤ α, 0 ≤ xl ≤ zl ≤ 1 − α, zj; j = l, d, denotes the measure of type-j workers that remain employed and xj; j = l, d, denotes the measure of type-j workers that are involuntarily underemployed.

Several remarks are in order. First, we consider the most general rationing rule that allows each type of unskilled worker to be underemployed (xi ≤ zi; i = d, l) and/or unemployed (zd ≤ α, zl ≤ 1 − α). Second, the formulation of the surplus in (B1) accounts for the fact that the reservation utility of unemployed workers of both types is zero. Finally, we assume that the utility levels under the optimal tax-and-transfer regime (hence, by continuity considerations, also under the perturbed tax-and-transfer regime) are bounded away from zero for both types of unskilled workers; hence, both types of unskilled workers will have positive working hours.

Rearranging (B2) yields

(B2’) xd + xl = ψ,

where \( \uppsi \equiv 1-\upalpha -\frac{\left(1-{z}^d-{z}^l\right){n}_{\ast}^d}{n_{\ast}^d-{n}_{\ast}^l} \).

Substituting for xl from (B2’) into (B1) and rearranging yields

(B3) \( S=\left({z}^d+{z}^l\right){\overset{\sim }{\mathrm{c}}}^d+\uppsi \left({\overset{\sim }{\mathrm{c}}}^l-{\overset{\sim }{\mathrm{c}}}^d\right)-\left({z}^d-{x}^d\right)g\left({n}_{\ast}^d\right)-{x}^dg\left({n}_{\ast}^l\right)-\left({x}^d+{z}^l-\uppsi \right) kg\left({n}_{\ast}^d\right)-\left(\uppsi -{x}^d\right) kg\left({n}_{\ast}^l\right) \).

Differentiating (B3) with respect to xd and rearranging yields

(B4) \( \frac{\partial S}{\partial {x}^d}=-\left(k-1\right)\left[g\left({n}_{\ast}^d\right)-g\left({n}_{\ast}^l\right)\right]<0 \),

where the inequality follows since \( {n}_{\ast}^d>{n}_{\ast}^l \), g is increasing, and k > 1. We conclude that xd = 0 and, by virtue of (B2’), that xl = ψ.

Differentiating (B3) with respect to zh upon rearrangement yields

(B5) \( \frac{\partial S}{\partial {z}^d}=\frac{n_{\ast}^d\left(k-1\right)g\left({n}_{\ast}^d\right)+{n}_{\ast}^d\left[{\overset{\sim }{\mathrm{c}}}^l- kg\left({n}_{\ast}^l\right)\right]-{n}_{\ast}^l\left[{\overset{\sim }{\mathrm{c}}}^d-g\left({n}_{\ast}^d\right)\right]}{n_{\ast}^d-{n}_{\ast}^l} \).

As \( {n}_{\ast}^d>{n}_{\ast}^l \) and k > 1, it follows by substituting \( {n}_{\ast}^l \) for \( {n}_{\ast}^d \) in the first term of the numerator of right-hand-side expression of (B5) that

(B6) \( \frac{\partial S}{\partial {z}^d}>\frac{n_{\ast}^l\left(k-1\right)g\left({n}_{\ast}^d\right)+{n}_{\ast}^d\left[{\overset{\sim }{\mathrm{c}}}^l- kg\left({n}_{\ast}^l\right)\right]-{n}_{\ast}^l\left[{\overset{\sim }{\mathrm{c}}}^d-g\left({n}_{\ast}^d\right)\right]}{n_{\ast}^d-{n}_{\ast}^l} \),

which, after rearrangement, yields

(B6’) \( \frac{\partial S}{\partial {z}^d}>\frac{n_{\ast}^d\left[{\overset{\sim }{\mathrm{c}}}^l- kg\left({n}_{\ast}^l\right)\right]-{n}_{\ast}^l\left[{\overset{\sim }{\mathrm{c}}}^d- kg\left({n}_{\ast}^d\right)\right]}{n_{\ast}^d-{n}_{\ast}^l} \).

As \( {n}_{\ast}^d>{n}_{\ast}^l \), for \( \frac{\partial S}{\partial {z}^d}>0 \) it suffices to show that the numerator of the right-hand-side of (B6’) is positive; that is

(B7) \( {n}_{\ast}^d\left[{\overset{\sim }{\mathrm{c}}}^l- kg\left({n}_{\ast}^l\right)\right]-{n}_{\ast}^l\left[{\overset{\sim }{\mathrm{c}}}^d- kg\left({n}_{\ast}^d\right)\right] \)> 0.

By virtue of the binding incentive-compatibility constraint ICld, under the optimal unperturbed tax-and-transfer regime

(B8) \( \underset{\varepsilon \to 0}{\lim}\left[{\overset{\sim }{\mathrm{c}}}^d- kg\left({n}_{\ast}^d\right)\right]=\underset{\delta \to 0}{\lim}\left[{\overset{\sim }{\mathrm{c}}}^l- kg\left({n}_{\ast}^l\right)\right]\equiv B>0 \),

where the inequality sign follows from our assumption that the utilities derived under the optimal tax-and-transfer regime are positive. Therefore,

(B9) \( \underset{\varepsilon \to 0,\delta \to 0}{\lim }{n}_{\ast}^d\left[{\overset{\sim }{\mathrm{c}}}^l- kg\left({n}_{\ast}^l\right)\right]-{n}_{\ast}^l\left[{\overset{\sim }{\mathrm{c}}}^d- kg\left({n}_{\ast}^d\right)\right]=B\left({n}_{\ast}^d-{n}_{\ast}^l\right)>0, \)where the inequality sign follows from (B8) and \( {n}_{\ast}^d>{n}_{\ast}^l. \) Thus, by continuity considerations, for sufficiently small ε and δ, the inequality (B7) holds. We thus conclude that \( \frac{\partial S}{\partial {z}^d}>0. \) Hence, zd = α.

Differentiating (B3) with respect to zl upon rearrangement yields

(B10) \( \frac{\partial S}{\partial {z}^l}=\frac{n_{\ast}^h\left[{\overset{\sim }{\mathrm{c}}}^l- kg\left({n}_{\ast}^l\right)\right]-{n}_{\ast}^l\left[{\overset{\sim }{\mathrm{c}}}^d- kg\left({n}_{\ast}^d\right)\right]}{n_{\ast}^d-{n}_{\ast}^l} \).

Noting that the expression on the right-hand-side of (B10) is identical to the expression on the right-hand-side of (B6’). By repeating the arguments used to establish the positive sign of \( \frac{\partial S}{\partial {z}^d} \), it therefore follows that \( \frac{\partial S}{\partial {z}^l} \)> 0. Hence, zl = 1 − α.

We conclude that under constrained efficient rationing, none of the unskilled workers are forced into unemployment. Moreover, the entire incidence of underemployment falls on the undeserving poor who are unable to mimic the deserving poor. We conclude that the suggested perturbation supplemented by the binding minimum wage violates none of the incentive-compatibility constraints.

II. Welfare gain

The total change in welfare is given by \( \Delta W=\varepsilon \left(1-{\beta}^l\right)-\updelta {\beta}^l=\varepsilon \left[1-\frac{2{\beta}^l}{\left(1-\alpha \right)}\right]>0 \), where the last equality follows as (1 − α)δ = (1 + α)ε (by construction of the perturbation) and the strict inequality follows from the presumption that βl < (1 − α)/2.

III. Nearly constrained efficient rationing

By virtue of the suggested perturbation, both types of unskilled workers strictly prefer the bundle \( \left({\overset{\sim }{c}}^d,{n}_{\ast}^d\right) \), referred to as an d-job, to the bundle \( \left({\overset{\sim }{c}}^l,{n}_{\ast}^l\right) \), referred to as a l-job, where the respective measures of available d-jobs and l-jobs are given by α and 1 − α. We consider an extension of the constrained efficient rationing rule: (i) a fraction 0≤q≤1 of the h-jobs is assigned to the deserving poor; (ii) an identical fraction of the l-jobs is assigned to the undeserving poor; and (iii) the remaining jobs are assigned randomly. Notice that when q = 1 rationing is constrained efficient, whereas rationing is random when q = 0. Let the utility of a deserving poor assigned to an d–job (l–job) be denoted by udd (udl), and the utility of an undeserving poor assigned to an d–job (l–job) be denoted by uld (ull). In light of the extended rationing rule, the expected utility derived by type-d and type-l workers is given, respectively, by:

(B11) EUd = [q + (1 − q)α]udd + [(1 − q)(1 − α)]udl,

(B12) EUl = [q + (1 − q)(1 − α)]ull + [(1 − q)α]uld,

and social welfare is given by:

(B13) W = βlEUl + βdEUd + (1 − βl − βd)Us.

Taking the limit when q → 1 implies that EUd ⟶ udd and EUl ⟶ ul. Recall that udd and ull are the utilities derived, respectively, by the deserving and the undeserving poor under the suggested perturbation with constrained efficient rationing. It follows by continuity considerations that the suggested perturbation yields an increase in social welfare if q is sufficiently close to 1. That is, there exists a \( \widehat{q} \) such that for any \( q\in \left(\widehat{q},1\right] \) the associated rationing rule attains a welfare improvement. Denoting such rationing rules as nearly constrained efficient establishes our argument.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Blumkin, T., Danziger, L. Deserving poor and the desirability of a minimum wage. IZA J Labor Econ 7, 6 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40172-018-0066-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40172-018-0066-7