Abstract

Background

While the Health Related Quality of Life of the children with congenital heart defects is primarily affected, caring for a child with birth defect has an impact on the family’s quality of life as well. Understanding the level of quality of life of the parents, which is likely to vary in different cultural settings, beliefs and parental educational status may help to implement educational programs and other interventional measures that may improve the HRQOL of parents of such children. This cross-sectional comparative study reports the health-related quality of life of mothers of children with congenital heart diseases in a sub-Saharan setting.

Results

Mean age of the mothers in the study group was 32.2 ± 7.1 years where as that of the control group was 30.5 ± 6.5 years (p = .054). One hundred-four children had congenital cardiac lesions classified as mild to moderate while 31 patients had severe lesions. On average, mothers in the study group showed poor performance on the Short Form-36 (SF-36) with statistically significant differences on all sub-scales including general health perception, physical functioning, role physical, role emotional, social functioning, bodily pain, vitality and mental health. Severity of the congenital heart defect was not associated with statistically significant difference in the health-related quality of life of the mothers.

Conclusions

Mothers of children with congenital heart disease in our study have significantly lower quality of life in all domains of SF-36 compared to the control group. Planning and devising a strategy to support these mothers may need to be part of management and clinical care of children with congenital heart diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The most commonly reported incidence of congenital heart defects is between 4 and 10 per 1000, clustering around 8 per 1000 live births [1, 2]. While the Health Related Quality of Life (HRQOL) of the children, adolescents and adults with congenital heart defects is primarily affected [3], caring for a child with birth defect has an impact on the family’s quality of life as well. Financial burden due to reasons such as traveling for care and medical costs, difficulty of interaction with those outside the family, emotional turmoil as a result of a sense of isolation because they feel different from their peers which increases their depression or mental health problems are some of the most important factors [4,5,6].

Understanding the level of quality of life of the parents, which is likely to vary in different cultural settings, beliefs and parental educational status may help to implement educational programs and other interventional measures that may improve the HRQOL of parents of such children [5]. In most sub-Saharan communities, child-care and upbringing is almost the sole responsibility of mothers. Furthermore, mothers may sometimes be blamed or discriminated for having a child with congenital birth defects, which in some cases may result in dissolution of marriage. This study sought to determine the HRQOL of mothers of children with congenital heart disease in a sub-Saharan setting where the access to definitive treatment is rarely available. We speculated that the added bad news that invasive treatments for congenital heart diseases are not readily/regularly available in country could make the level of anxiety of the mothers even worse.

Methods

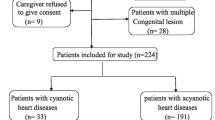

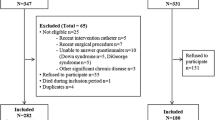

This was a cross-sectional study comparing the HRQOL of mothers of children with congenital heart diseases who came for regular cardiac follow-up at the Addis Ababa University hospital (Tikur Anbessa hospital) and mothers who visited the outpatient pediatric clinics for other acute illnesses. A sample of 135 mothers in each group was calculated using Sample sizes for two Independent samples, Continuous outcome, n = 2(Zδ/E)2, where δ (standard deviation) taken from another study was 16.71 and the margin of error (E) was taken to be within 4 points. Mothers were included in the study after written consent was obtained. Consecutive mothers coming to the clinics From February 1 to April 30, 2015 were included in the sample.

The standard SF-36 was used to collect the data. The SF-36 consists of 36 items (questions) measuring physical and mental health status in relation to 8 health concepts: physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health, bodily pain, general health perceptions, vitality (energy/fatigue), social functioning, role limitations due to emotional health, general mental health (psychological distress/wellbeing). The questionnaire was translated into Amharic, a working language in the country with a view of using translators in case the mothers prefer any other local language. However, the participants included in this study by chance spoke the language avoiding the need for translators. The questionnaire was also adapted in a way it fits the cultural background of the society. The principal investigator trained the data collectors on how to use the form and how to collect the data. Data was collected in an interview with trained data collectors. Data on age, educational level, marital status, monthly income, general health, physical functioning and others was collected.

Statistical methods

Data was entered into SPSS version 20 for windows and analyzed. Demographic variables were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Continuous variables were displayed as mean ± standard deviation. HRQOL parameters were compared between the two groups of mothers using t-test for two independent samples. Significance was taken to be at a p value of < .05.

Results

Mean age of the mothers in the study group was 32.2 ± 7.1 years where as that of the control group was 30.5 ± 6.5 years (p value = .054). Socio-demographic data of the study and control groups is shown on Table 1. Regarding the distribution of congenital heart diseases in the children of mothers in the study group Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD) was the most common. Overall, 104 of the children belonging to mothers in the study group had mild to moderate lesions while 31 children had severe forms of congenital heart diseases (Table 2).

On average, mothers in the study group showed poor performance on the SF-36 with statistically significant differences on all sub-scales including general health perception, physical functioning, role physical, role emotional etc. Table 3 shows comparison of the performance of mothers in the study group and the control group on SF-36 sub-scales.

When the sub-group of mothers of children with severe congenital cardiac lesions was compared with those having children with mild to moderate congenital cardiac lesions (Table 4), there was no statistically significant difference in any of the sub-scales of SF-36.

Discussion

Our study shows that mothers with children having congenital heart disease have a lower performance compared with mothers of children having minor acute illnesses in all domains of health-related quality of life. Other studies have also demonstrated that parents of children with heart diseases or other chronic illnesses may have higher level of stress compared with parents of children with other minor illnesses [5, 7,8,9,10]. They are generally at a high risk of anxiety, distress and hopelessness [9]. Studies have also shown that mothers have a more severe depression and emotional reactions compared to fathers [11]. This may even be more important in sub-Saharan settings where childcare and upbringing is mainly responsibility of the mothers and mothers have less social support and less access to information regarding their children’s illnesses. Social support and access to information has been shown to positively impact quality of life of such mothers. Besides, the unavailability of cardiac surgery or percutaneous interventions for congenital heart diseases in this part of the world is likely to play a role in adversely affecting the quality of life of mothers in various ways: (1) the news that the clinical condition is not treatable in country or that the treatment is very expensive may create a sense of frustration; (2) unoperated congenital heart diseases may lead to frequent clinical decompensation, requiring frequent clinical consultation and marked limitation of the child’s physical activity; (3) some untreated congenital heart diseases may be associated with failure to thrive and/or developmental delay, adding to the concern and worry of the mothers.

Addressing quality of life of mothers is important in that maternal depression and anxiety can adversely affect the care of a child with chronic condition like congenital heart diseases [12, 13]. Parents, especially mothers may need continuous psychosocial support before or after the child is treated as some studies indicate that the psychological stress and impaired quality of life may continue long after the child has undergone corrective surgery or invasive treatment [14].

Though some studies have suggested that maternal symptoms of depression and anxiety is related to severity of the congenital cardiac lesion [6], our study did not demonstrate any difference in any of the domains between those with mild to moderate and severe cardiac lesions. DeMaso et al. [13] have also shown that diagnosis of a severe cyanotic heart defect does not appear to make a child more likely to have emotional disorder compared to the ones with non-severe, in the absence of other factors. However, it is also possible that our finding may probably be related to the differences in the study settings, knowledge of mothers regarding the treatment and prognosis of each of the cardiac lesions, scarcity of intervention for any of the congenital cardiac lesions in our study setting and other related factors compared to those studies which concluded that severity of illness was important.

Conclusions

Mothers of children with congenital heart disease in our study have significantly lower quality of life in all domains of SF-36 compared to the control group. Planning and devising a strategy to support these mothers may need to be part of management and clinical care of children with congenital heart diseases.

Abbreviations

- CHD:

-

congenital heart disease

- SF-36:

-

Short Form-36

- SPSS:

-

statistical package for social sciences

- VSD:

-

ventricular septal defect

- ASD:

-

atrial septal defect

- PDA:

-

patent ductus arteriosus

- AVSD:

-

atrioventricular septal defect

- TGA:

-

transposition of the great arteries

- DORV:

-

double outlet right ventricle

- TAPVR:

-

total anomalous pulmonary venous return

- SD:

-

standard deviation

References

Brennan P, Young ID. Congenital heart malformations: aetiology and associations. Semin Neonatol. 2001;6:17–25.

Bolisetty S, Daftary A, Ewald D, Knight B, Wheaton G, et al. Congenital heart defects in central Australia. Med J Aust. 2004;180:614–7.

Nousi D, Christou A. Factors affecting the quality of life in children with congenital heart disease. Health Sci J. 2010;4:94–100.

Lemacks J, Fowles K, Mateus A, Thomas K. Insights from parents about caring for a child with birth defects. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10:3465–82.

Edraki M, Kamali M, Beheshtipour N, Amoozgar H, Zare N, Montaseri S. The effect of educational program on the quality of life and self-efficacy of the mothers of the infants with congenital heart disease: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Commun Nurs Midwifery. 2014;2:51–9.

Solberg Ø, Grønning Dale MT, Holmstrøm H, Eskedal LT, Landolt MA, Vollrath ME. Long term symptoms of depression and anxiety in mothers of infants with congenital heart defects. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011;36:179–87.

Arafa MA, Zaher SR, El-Dowety AA, Moneeb DE. Quality of life of parents of children with heart disease. Health and Quality of life outcomes. Health Qual Life Out 2008;6:91.

Lawoko S, Soares JJ. Psychosocial morbidity among parents of children with congenital heart disease: a prospective longitudinal study. Heart Lung. 2006;35:301–14.

Lawoko S, Soares JJ. Quality of life among parents of children with congenital heart disease, parents of children with other diseases and parents of healthy children. Qual Life Res. 2003;12:655–66.

Hatzmann J, Maurice-Stam H, Heymans HSA, Grootenhuis MA. A predictive model of health related quality of life of parents of chronically ill children: the importance of care-dependency of their child and their support system. Health Qual Life Out. 2009;7:72.

Bevilacqua F, Palatta S, Mirante N, Cuttini M, Seganti G, Dotta A. Birth of a child with congenital heart disease: emotional reactions of mothers and fathers according to time of diagnosis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;26:1249–53.

Downey G, Coyne JC. Children of depressed parents: an integrative review. Psychol Bull. 1990;108:50–76.

DeMaso DR, Lk Campis, Wypij D, et al. The impact of maternal perceptions and medical severity on the adjustment of children with congenital heart disease. J Pediatr Psychol. 1991;16:137–49.

Ljubica N, Ilija D, Frosina R, Saiti S, Paunovska ST, Mitrev Z. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of the parenting styles, coping strategies and perceived stress in mothers of children who have undergone cardiac interventions. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2013;84:1809–14.

Authors’ contributions

LS: developed the proposal collected the data and wrote and rewrote the draft manuscript. ET: helped in the selection of the study topic, reviewed the draft manuscript critically and wrote the final version of the manuscript in its current form. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of the Pediatric Cardiac clinic and regular Pediatric Outpatient department staff for their generous assistance in the conduct of the study. We also extend our gratitude to the department of Pediatrics and ethics review committee for allowing us to do this study. Last but not least, we are indebted to the mothers who willingly participated in this study.

Authors’ information

LS: was resident in the Department of Pediatrics & Child Health, School of Medicine, Addis Ababa University from 2012 to 2015. She is currently teaching at School of Medicine, Wolaita Sodo University. ET: consultant Pediatric cardiologist at the School of Medicine, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Supporting data are available on request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Institutional review committee of the School of Medicine of Addis Ababa University (Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital) in Addis Ababa approved the study. Written consent to participate in the study was obtained from the study participants.

Funding

This study got small grant from the postgraduate director’s office as part of student thesis for Lidia Sileshi (no grant number assigned).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Sileshi, L., Tefera, E. Health-related quality of life of mothers of children with congenital heart disease in a sub-Saharan setting: cross-sectional comparative study. BMC Res Notes 10, 513 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-017-2856-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-017-2856-6