Abstract

Background

Rubella infections in susceptible women during early pregnancy often results in congenital rubella syndrome (CRS). World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends that countries without vaccination programmes to assess the burden of rubella infection and CRS. However; in many African countries there is limited data on epidemiology of rubella infection and CRS. This review was undertaken to assess the serological markers and genotypes of rubella virus on the African continent in order to ascertain the gap for future research.

Findings

A systematic search of original literatures from different electronic databases using search terms such as ‘rubella’ plus individual African countries such as ‘Tanzania’, ‘Kenya’, ‘Nigeria’ etc. and different populations such as ‘children’, ‘pregnant women’ etc. in different combinations was performed. Articles from countries with rubella vaccination programmes, outbreak data and case reports were excluded. Data were entered in a Microsoft Excel sheet and analyzed. A total of 44 articles from 17 African countries published between 2002 and 2014 were retrieved; of which 36 were eligible and included in this review. Of all population tested, the natural immunity of rubella was found to range from 52.9 to 97.9 %. In these countries, the prevalence of susceptible pregnant women ranged from 2.1 to 47.1 %. Rubella natural immunity was significantly higher among pregnant women than in general population (P < 0.001). Acute rubella infection was observed to be as low as 0.3 % among pregnant women to 45.1 % among children. All studies did not ascertain the age-specific prevalence, thus it was difficult to calculate the rate of infection with increase in age. Only two articles were found to report on rubella genotypes. Of 15 strains genotyped; three rubella virus genotypes were found to circulate in four African countries.

Conclusion

Despite variations in serological assays, the seroprevalence of IgG rubella antibodies in Africa is high with a substantial number of women of childbearing age being susceptible to rubella infection. Standardized sero-epidemiological data in various age groups as well as CRS data are important to implement cost-effective vaccination campaigns and control strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Findings

Background

Rubella or ‘German measles’ is a mild viral disease caused by the rubella virus. Rubella is RNA virus in the family Togaviridae and is transmitted by droplets, direct contact or vertically from pregnant woman to the fetus [1]. The virus is worldwide distributed and is of public health concern due to its teratogenic effects. Infections in susceptible women during early pregnancy may results into multiple birth defects known as congenital rubella syndrome (CRS). Each year more than 100,000 children particularly in developing countries are born with CRS [2–4]. The CRS is mainly characterized by a triad of congenital heart diseases, congenital cataracts, and deafness; and many other defects [5].

Rubella is among many vaccine-preventable diseases; the main goal of vaccination is to reduce the incidence of rubella virus infection and CRS. In countries with vaccination programme especially in developed countries, the number of CRS cases have been markedly reduced [6, 7]. Despite the decrease in number of CRS cases worldwide, rubella remains a public health problem in Africa [3, 4]. Lack of vaccination programme in children contributes to increase in CRS cases because children usually harbour and spread the infection in community including susceptible pregnant women [8].

Despite high prevalence of congenital malformations in Africa [9, 10] few countries have introduced rubella vaccination in their national immunization programs to reduce incidence of acute rubella infections and CRS cases. World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that countries without national rubella vaccination programmes should assess the burden of rubella and CRS through sero-epidemiological surveys that may be implemented in parallel with measles surveillance [11]. However, there is limited data on epidemiology of rubella and CRS in Africa. The main objective of this review was to determine the gap of literatures based on WHO recommendations and accuracy of data to be used as baseline before rubella vaccination is introduced.

Methods

Following PRISMA checklist (Additional file 1) systematic review was done. Systematic search for literature/original articles published in english focusing on rubella sero-epidemiology in Africa was performed using online database (PubMed/Medline, Embase, Popline, Global Health, Google Scholar and Web of Knowledge). The search was performed using terms; ‘rubella’ plus individual African countries like Tanzania, Kenya, Liberia, Nigeria etc., seroprevalence, pregnant women, adolescents, children in different combinations.

New links displayed in each abstract were followed and more abstracts were retrieved. Abstracts were carefully reviewed to exclude all articles published before 2002. Bibliographies of the retrieved articles were carefully reviewed and relevant articles published within the time frame were also retrieved. The search revealed 44 articles from 17 countries published between 2002 and 2014. Further analysis excluded; 2 case reports, 4 articles with outbreak data (WHO surveillance) and 2 articles from countries with national rubella vaccination programme as per WHO report (http://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/burden/vpd/surveillance_type/active/Rubella_map_schedule.jpg?ua=1) (Fig. 1).

Data extraction and analysis

Eligible articles were reviewed independently by two authors. The data were recorded in excel sheet containing the subtitles such as region (country), study design, study population, age range, technique used, cut-off points, Immunoglobulin M (IgM) and Immunoglobulin G (IgG) seroprevalence, number of samples tested negative, whether the study was conducted in rural or urban settings, season, strain of circulating virus (if any), author and date of publication. Data were manually analysed to obtain proportions of natural immunity. Proportion test using STATA version 11 was done to establish statistical differences.

Results

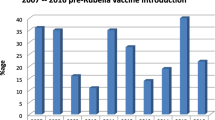

Of 36 articles reviewed, 20 (55.5 %) were conducted between 2007 and 2014. In these articles; population tested included pregnant women aged between 15 and 50 years, children aged from 0 to 18 years and general adult population aged between 19 and 62 years. The rubella natural immunity in these countries ranged from 52.9 % among pregnant women in Benin Nigeria to 99.3 % among adults in Uganda (Tables 1 and 2). High level of natural immunity was observed in population aged between 20 and 40 years.

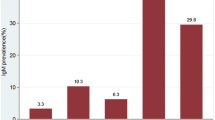

Of 36 articles reviewed, 22 (61.1 %) articles reported sero-prevalence of rubella-specific antibodies among pregnant women. The natural immunity of rubella among pregnant women was found to range from 52.9 % in Benin, Nigeria to 97.9 % in Zaria, Nigeria; implying that pregnant women susceptible to rubella infection in these countries range from 2.1 to 47.1 % based on different cut off points used. Overall, of 7215 pregnant women tested, 6494 (90 %, 95 % CI; 83.9–85.6) were found to have natural immunity compared to 6343 (84.8 %, 95 % CI; 89.2–90.7) of 7480 of general population tested (P < 0.001). Only 12 (33.3 %) articles reported IgM seroprevalence. In these articles, IgM seroprevalence was found to range from 0.3 % among pregnant women in Mwanza, Tanzania to 45.1 % among children in Jos, Nigeria (Fig. 2).

From few studies which determined seroprevalence in urban or in rural settings; the prevalence of rubella-specific IgG from urban settings ranged from 85.1 % in Morocco to 98.2 % in Zaria Nigeria (Tables 1 and 2) while in rural population it ranged from 81.5 % in Morocco to 96.8 % in Maputo, Mozambique. While, of the 22 articles which reported rubella-specific seroprevalence rates in pregnant women, only 6 articles categorized the study participants in relation to residence (rural or urban). No significant difference in natural immunity was observed between these two settings (Tables 1 and 2).

Regarding the techniques used in these studies all studies used Enzyme immunoassay (EIA)/enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) techniques with significant variation of the cut off points of these assays. In addition, a total of 11 (30.5 %) studies did not specify the cut off points used.

Moreover, only two articles assessed rubella virus genotypes in Africa. In five countries where rubella virus were obtained and genotyped, it was revealed that at least three genotypes existed in Africa. Genotype 1E exists in Morocco and Sudan; 1G in Uganda, Sudan and Cote d’Ivore while genotype 2B exists in South Africa and Sudan. Of 15 strains genotyped between 2001 and 2010, 7 were typed as 1E, 5 as 2B and 3 as 1G genotypes. Results indicate that about 20 % of rubella virus strains circulating in Africa are non 1E and 2B.

Discussion

Data from different African countries suggests that rubella virus is common. In addition these data indicate that there is significant number of susceptible women of childbearing age signifying the potential risk for giving birth to a child with CRS. High seroprevalence rates suggest that rubella virus is constantly circulating in Africa continent. Majority of population acquire infections in early childhood which accounts for high natural immunity in adolescence and among childbearing women [12–14].

The general rubella-specific IgG seroprevalence in pre-vaccination era in Africa is comparable with other regions in Southern America, India and Europe before vaccination [15–19]. However, the level of natural immunity in these studies is lower than the immunity currently reported in Europe; this might be due to on-going vaccination programmes in developed countries [20, 21].

Compared to the data from Europe there is a wide variation of rubella susceptibility in Africa indicating that transmission rates differ among regions. This could also be attributed to lack of standardized assays as confirmed in this review. Data from Europe are before 1970s while for Africa are of 2000s. This might possibly indicate higher population density variation worldwide.

Generally, no significant difference was observed for IgG seroprevalence between urban and rural settings in Africa. Similar findings have been observed in South America, India and Asia [18, 22].

As documented in other regions; higher IgM sero-prevalence rate was observed in children and adolescents than in adults, with the trend of IgM positivity decreasing with increase in age [14, 23–28]. This indicates high transmission rates during childhood emphasizing importance of vaccination in this age group [29].

There are little information available on genotypes of rubella viruses in Africa [30, 31]. Of ten genotypes known todate (1A, 1B, 1C, 1D, 1E, 1F, 1G, 2A, 2B and 2C) worldwide, 1E and 2B have been found to have a wide geographical distribution [29, 32, 33]. This might not represent a true picture in Africa because, of 15 strains genotyped between 2001 and 2010 in Africa; three (1E, 2B and 1G) genotypes were detected with 20 % of strains being non 1E and 2B [30, 31]. The rare genotype 1G which in Africa has been reported in Uganda has been previously observed in Israel, Europe and Brazil [34]. This necessitates the need for more phylogenetic studies in Africa which will be useful in monitoring genotypes changes in future.

Generally this review gives an overview of the current situation of rubella virus infection in Africa which may be useful for future control strategies. However, a number of challenges/drawbacks have been observed which accounts for limitations in some of the epidemiological information. These challenges include: different serological assays utilizing different reagents and cut off points have been used, making a comparison between the studies difficult. In addition, some of the articles did not document cut-off points for IgG seroprevalence. Most of the articles did not assess both IgM and IgG seroprevalence at one point in time. This might cause inaccurate information about susceptible individuals in some studies because some of the IgG-negative individuals were probably IgM positive. The magnitude of IgM seropositivity might have been overestimated due to high false positive rate of IgM assays. Therefore the data provided in this review underscore the need for standardizing surveillance in Africa for rubella virus infection. Majority of the articles did not indicate whether the participants were from rural or urban settings. Therefore it was difficult to assess the level of immunity on these two populations in the continent. Of more important, age specific seroprevalence and incidence rates were not reported in majority of the articles. Therefore, this information is not very clear in Africa making the basis of age limit for vaccination questionable. Another, information which is not clear regarding rubella infection in Africa is seasonality as none of the articles reviewed investigated on this aspect. Lastly, none of the studies assessed the sero-conversion rate during the course of the pregnancy hence it is difficult to estimate the potential risk for CRS in Africa. In addition, the data of the magnitude of CRS was not documented emphasizing the need for surveillance of CRS in Africa [35].

Conclusion

There are few studies in Africa which have investigated on molecular epidemiology of rubella virus, therefore little is known regarding genotypes of rubella virus strains circulating in Africa. In addition very few studies have compared epidemiology of rubella virus between urban and rural settings. Finally, descriptions of assay/techniques used were very poor. There is a need to follow WHO guidelines when conducting epidemiological research so that data can easily be pooled and help in policy formulation.

Abbreviations

- CRS:

-

congenital rubella syndrome

- ELISA:

-

enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

- EIA:

-

enzyme immunoassay

- IgG:

-

immunoglobulin G

- IgM:

-

immunoglobulin M

- WHO:

-

World health organisation

References

Hamkar R, Jalilvand S, Mokhtari-Azad T, Nouri Jelyani K, Dahi-Far H, Soleimanjahi H, Nategh R. Assessment of IgM enzyme immunoassay and IgG avidity assay for distinguishing between primary and secondary immune response to rubella vaccine. J Virol Methods. 2005;130(1):59–65.

Best JM, Castillo-Solorzano C, Spika JS, Icenogle J, Glasser JW, Gay NJ, Andrus J, Arvin AM. Reducing the global burden of congenital rubella syndrome: report of the World Health Organization Steering Committee on research related to measles and rubella vaccines and vaccination, June 2004. J Infect Dis. 2005;192(11):1890–7.

Binnicker M, Jespersen D, Harring J. Multiplex detection of IgM and IgG class antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii, rubella virus, and cytomegalovirus using a novel multiplex flow immunoassay. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2010;17(11):1734–8.

Katow S. Rubella virus genome diagnosis during pregnancy and mechanism of congenital rubella. Intervirology. 1999;41(4–5):163–9.

Lindquist J, Plotkin S, Shaw L, Gilden R, Williams M. Congenital rubella syndrome as a systemic infection. Studies of affected infants born in Philadelphia, USA. Br Med J. 1965;2(5475):1401.

Ukkonen P. Rubella immunity and morbidity: impact of different vaccination programs in Finland 1979–1992. Scand J Infect Dis. 1996;28(1):31–5.

Noah ND, Fowle SE. Immunity to rubella in women of childbearing age in the United Kingdom. BMJ. 1988;297:1301–4.

Organization WH. WHO position paper on rubella vaccines. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2000;75:161–72.

Howson C, Christianson A, Modell B. Controlling birth defects: reducing the hidden toll of dying and disabled children in lower-income countries. Washington: Disease Control Priorities Project; 2008.

Mashuda F, Zuechner A, Chalya PL, Kidenya BR, Manyama M. Pattern and factors associated with congenital anomalies among young infants admitted at Bugando medical centre, Mwanza, Tanzania. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7(1):195.

Organization WH. Report of a meeting on preventing congenital rubella syndrome: immunization strategies, surveillance needs. Geneva: 2000.

Kombich JJ, Muchai PC, Tukei P, Borus PK. Rubella seroprevalence among primary and pre-primary school pupils at Moi’s Bridge location, Uasin Gishu District, Kenya. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):269.

Manirakiza A, Kipela JM, Sosler S, Daba RM, Gouandjika-Vasilache I. Seroprevalence of measles and natural rubella antibodies among children in Bangui, Central African Republic. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):327.

Junaid SA, Akpan KJ, Olabode AO. Sero-survey of rubella IgM antibodies among children in Jos, Nigeria. Virol J. 2011;8(1):1–5.

De Azevedo Neto R, Silveira A, Nokes D, Yang H, Passos S, Cardoso M, Massad E. Rubella seroepidemiology in a non-immunized population of Sao Paulo State, Brazil. Epidemiol Infect. 1994;113(01):161–73.

Preblud SR, Serdula MK, Frank JA Jr, Brandling-Bennett AD, Hinman AR. Rubella vaccination in the United States: a ten-year review. Epidemiol Rev. 1980;2:171–94.

Gandhoke I, Aggarwal R, Lal S, Khare S. Seroprevalence and incidence of rubella in and around Delhi (1988–2002). Indian J Med Microbiol. 2005;23(3):164.

Dowdle W, Ferreira W, De Salles Gomes L, King D, Kourany M, Madalengoitia J, Pearson E, Swanston W, Tosi H, Vilches A. WHO collaborative study on the sero-epidemiology of rubella in Caribbean and Middle and South American populations in 1968. Bull World Health Organ. 1970;42(3):419.

Doroudchi M, Dehaghani AS, Emad K, Ghaderi A. Seroepidemiological survey of rubella immunity among three populations in Shiraz, Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterr Health J. 2001;7:128–38.

Pebody R, Edmunds W, Conyn-van Spaendonck M, Olin P, Berbers G, Rebiere I, Lecoeur H, Crovari P, Davidkin I, Gabutti G. The seroepidemiology of rubella in western Europe. Epidemiol Infect. 2000;125(02):347–57.

Galazka A. Rubella in Europe. Epidemiol Infect. 1991;107(01):43–54.

Bartoloni A, Bartalesi F, Roselli M, Mantella A, Dini F, Carballo ES, Barron VP, Paradisi F. Seroprevalence of varicella zoster and rubella antibodies among rural populations of the Chaco region, south-eastern Bolivia. Trop Med Int Health. 2002;7(6):512–7.

Mitiku K, Bedada T, Masresha B, Kegne W, Nafo-Traoré F, Tesfaye N, Beyene B. The epidemiology of rubella disease in Ethiopia: data from the measles case-based surveillance system. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(suppl 1):S239–42.

Bamgboye A, Afolabi K, Esumeh F, Enweani I. Prevalence of rubella antibody in pregnant women in Ibadan, Nigeria. West Afr J Med. 2004;23(3):245–8.

Ogbonnaya EC, Chinedum EK, John A, Esther A. Survey of the sero-prevalence of IgM antibodies in pregnant women infected with rubella virus. J Biotechnol Pharm Res. 2012;3:10–4.

Pennap G, Amauche G, Ajoge H, Gabadi S, Agwale S, Forbi J. Serologic survey of specific rubella virus IgM in the sera of pregnant women in Makurdi, Benue State, Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2009;13(2):69–73.

Onakewhor J, Chiwuzie J. Seroprevalence survey of rubella infection in pregnancy at the University of Benin Teaching Hospital, Benin City, Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2011;14(2):140–5.

Mwambe B, Mirambo MM, Mshana SE, Massinde AN, Kidenya BR, Michael D, Morona D, Majinge C, Groß U. Sero-positivity rate of rubella and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care in Mwanza, Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):95.

Organization WH. Global distribution of measles and rubella genotypes—update. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2006;81(51/52):474–9.

Caidi H, Abernathy ES, Benjouad A, Smit S, Bwogi J, Nanyunja M, El Aouad R, Icenogle J. Phylogenetic analysis of rubella viruses found in Morocco, Uganda, Cote d’Ivoire and South Africa from 2001 to 2007. J Clin Virol. 2008;42(1):86–90.

Omer A, Abdel Rahim EH, Ali EE, Jin L. Primary investigation of 31 infants with suspected congenital rubella syndrome in Sudan. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16(6):678–82.

Zhou Y, Ushijima H, Frey TK. Genomic analysis of diverse rubella virus genotypes. J Gen Virol. 2007;88(3):932–41.

Abernathy ES, Hübschen JM, Muller CP, Jin L, Brown D, Komase K, Mori Y, Xu W, Zhu Z, Siqueira MM. Status of global virologic surveillance for rubella viruses. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(suppl 1):S524–32.

Hübschen JM, Yermalovich M, Semeiko G, Samoilovich E, Blatun E, De Landtsheer S, Muller CP. Co-circulation of multiple rubella virus strains in Belarus forming novel genetic groups within clade 1. J Gen Virol. 2007;88(7):1960–6.

Robertson SE, Featherstone DA, Gacic-Dobo M, Hersh BS. Rubella and congenital rubella syndrome: global update. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2003;14(5):306–15.

Adewumi M, Olusanya R, Oladunjoye B, Adeniji J. Rubella IgG antibody among Nigerian pregnant women without vaccination history. Afr J Clin Exp Microbiol. 2012;14(1):40–4.

Agbede O, Adeyemi O, Olatinwo A, Salisu T, Kolawole O. Sero-prevalence of antenatal rubella in UITH. Open Public Health J. 2011;4:10–6.

Obijimi O, Ajetomobi A, Sule W, Oluwayelu D. Prevalence of rubella virus-specific immunoglobulin-g and-m in pregnant women attending two tertiary hospitals in southwestern Nigeria. Afr J Clin Exp Microbiol. 2013;14(3):134–9.

Onwere S, Chigbu B, Aluka C, Kamanu C, Okoro O, Waboso F, Ndukwe P, Onwere A, Akwuruoha E, Ezirim E. Serologic survey of rubella virus IgG in an African obstetric population. J Med Investig Pract. 2014;9(1):5.

Amina M-D, Oladapo S, Habib S, Adebola O, Bimbo K, Daniel A. Prevalence of rubella IgG antibodies among pregnant women in Zaria, Nigeria. Int Health. 2010;2(2):156–9.

Oyinloye S, Amama C, Daniel R, Ajayi B, Lawan M. Seroprevalence survey of rubella antibodies among pregnant women in Maiduguri, Borno State, Nigeria. Afr J Clin Exp Microbiol. 2014;15(3):151–7.

Kolawole OM, Anjorin EO, Adekanle DA, Kolawole CF, Durowade KA. Seroprevalence of rubella IgG antibody in pregnant women in Osogbo, Nigeria. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5(3):287.

Hamdan HZ, Abdelbagi IE, Nasser NM, Adam I. Seroprevalence of cytomegalovirus and rubella among pregnant women in western Sudan. Virol J. 2011;8:217.

Country A, Sudan RYEF, Eldaif WA, Mustafa Eltigani Mustafa MM. Frequency of rubella IgG antibodies in pregnant women attending antenatal clinics at Khartoum state. Asian J Biomed Pharm Sci. 2014;4(31):15–7.

Hamdan HZ, Abdelbagi IE, Nasser NM, Adam I. Seroprevalence of cytomegalovirus and rubella among pregnant women in western Sudan. Virol J. 2011;8(217):1–4.

Barreto J, Sacramento I, Robertson SE, Langa J, Gourville E, Wolfson L, Schoub BD. Antenatal rubella serosurvey in Maputo, Mozambique. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11(4):559–64.

Linguissi LSG, Nagalo BM, Bisseye C, Kagoné TS, Sanou M, Tao I, Benao V, Simporé J, Koné B. Seroprevalence of toxoplasmosis and rubella in pregnant women attending antenatal private clinic at Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2012;5(10):810–3.

Tahita MC, Hübschen JM, Tarnagda Z, Ernest D, Charpentier E, Kremer JR, Muller CP, Ouedraogo JB. Rubella seroprevalence among pregnant women in Burkina Faso. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13(1):164.

Kombich J. Seroprevalence of natural rubella antibodies among antenatal attendees at Moi teaching and Referral Hospital, Eldoret, Kenya. J Infect Dis Immunol Tech. 2012;1(1). doi:10.4172/2329-9541.1000102.

Corcoran C, Hardie DR. Seroprevalence of rubella antibodies among antenatal patients in the Western Cape: original article. S Afr Med J. 2005;95(9):688–90.

Fokunang C, Chia J, Ndumbe P, Mbu P, Atashili J. Clinical studies on seroprevalence of rubella virus in pregnant women of Cameroon regions. Afr J Clin Exp Microbiol. 2010;11(2):79–94.

De Paschale M, Ceriani C, Cerulli T, Cagnin D, Cavallari S, Cianflone A, Diombo K, Ndayaké J, Aouanou G, Zaongo D. Antenatal screening for Toxoplasma gondii, Cytomegalovirus, rubella and Treponema pallidum infections in northern Benin. Trop Med Int Health. 2014;19(6):743–6.

Adesina O, Adeniji J, Adeoti M. Rubella IgG antibody in women of child-bearing age in Oyo state. Afr J Clin Exp Microbiol. 2008;9(2):78–81.

Okolo MO, Stephen E, Okwori AEJ. Seroprevalence of rubella antibodies among apparently healthy individuals in Vom, Nigeria. J Sci Multidiscip Res. 2013;2(1):22–4.

Lewis RF, Braka F, Mbabazi W, Makumbi I, Kasasa S, Nanyunja M. Exposure of Ugandan health personnel to measles and rubella: evidence of the need for health worker vaccination. Vaccine. 2006;24(47):6924–9.

Ouyahia A, Segueni A, Laouamri S, Touabti A, Lacheheb A. Seroprevalence of rubella among women of child bearing age. Is there a need for a rubella vaccination? Int J Public Health Epidemiol. 2013;2(1):56–9.

Dromigny JA, Nabeth P, Perrier Gros Claude JD. Evaluation of the seroprevalence of rubella in the region of Dakar (Senegal). Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8(8):740–3.

Hashem M, Husein MH, Saleh DA, Abdelhai R, Eltahlawy E, Esmat H, Horeesh N, Abdalla M, Moustafa N, El-Gohary A. Rubella: serosusceptibility among Egyptian females in late childhood and childbearing period. Vaccine. 2010;28(44):7202–6.

Olajumoke OA, Christianah A, Morrison O, Sulaimon AA, Babajide SB, Isaac AA, Grace OA, Abiodun TS. Seroprevalence of human Cytomegalovirus and Rubella virus antibodies among anti-retroviral naive HIV patients in Lagos. IJTDH. 2014;4(9):984–92.

Caidi H, Bloom S, Azilmaat M, Benjouad A, Reef S, El Aouad R. Rubella seroprevalence among women aged 15–39 years in Morocco. East Mediterr Health J. 2009;15(3):526–31.

Authors’ contributions

MMM, MM and SEM participated in literature search, MMM and SEM analysed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. UG and SA critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support obtained from Mr Yanga Machimu in obtaining some of full articles used in this review. This review was supported by research grant from CUHAS to MMM.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Mirambo, M.M., Majigo, M., Aboud, S. et al. Serological makers of rubella infection in Africa in the pre vaccination era: a systematic review. BMC Res Notes 8, 716 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1711-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1711-x