Abstract

Background

Improving maternal health is one of the eight millennium development goals to reduce maternal mortality (MM) by three quarters between 1990 and 2015. Institutional delivery is considered to be the most critical intervention in reducing MM and ensuring safe motherhood. However, the level of maternal morbidity and mortality in Ethiopia are among the highest in the world and the proportion of births occurring at health facilities is very low. This study examined the individual and community level factors associated with institutional delivery in Ethiopia.

Methods

Data from the 2011 Ethiopian demographic and health survey were used to identify individual and community level factors associated with institutional delivery among women who had a live birth during the 5 years preceding the survey. Taking into account the nested structure of the data, multilevel logistic regression analysis has been employed to a nationally representative sample of 7757 women nested with in 595 communities.

Results

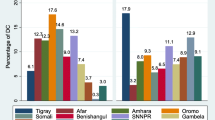

At the individual level; higher educational level of the women (AOR = 3.60; 95 % CI 2.491–5.214), women from richest households (AOR = 1.74; 95 % CI 1.143–2.648) and increased ante natal care attendance (AOR = 4.43; 95 % CI 3.405–5.751) were associated with institutional delivery. Additionally, at the community level; urban residence (AOR = 4.74; 95 % CI 3.196–7.039), residing in communities with high proportion of educated women (AOR = 1.71; 95 % CI 1.256–2.319) and residing in communities with high ANC utilization rate (AOR = 1.55; 95 % CI 1.132–2.127) had a significant effect on institutional delivery. Also region and distance to health facility showed significant association with institutional delivery. The random effects showed that the variation in institutional delivery service utilization between communities was statistically significant.

Conclusion

Both individual and community level factors are associated with institutional delivery service uptake. As a result, further research is needed to better understand why these factors may affect institutional delivery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Every day women die from pregnancy and birth related complications. Globally, in 2010 there were 287,000 maternal deaths of which developing countries account for 99 % with Sub Saharan Africa alone accounting for 56 %. Maternal mortality (MM) remains unacceptably high and has become major challenge in most developing countries including Ethiopia (MM of 676/100,000 live births) where maternal mortality and morbidity levels are among the highest in the world [1, 2].

About 80 % of maternal deaths are due to causes directly related to pregnancy and child birth. The major causes of maternal deaths are hemorrhage, infections, unsafe abortion, obstructed labour and hypertension during pregnancy. Though many of these complications are unpredictable, almost all could have been prevented by ensuring institutional delivery services as timely management and treatment can make the difference between life and death [3–5].

Improving maternal health requires increasing the proportion of mothers who are giving birth at health institutions and attended by skilled health workers. The statistics revealed that nearly all births in developed countries, 61.9 % in less developed countries, 46.9 % in south central Asia and 33.7 % in eastern Africa were attended by skilled health workers [6]. In Ethiopia, despite the progress that has been made to improve maternal and child health, the proportion of births occurring at health institutions is still very low (10 %) [7] and it has remained as an unaddressed top priority of the country [8, 9].

Research conducted in different countries shows that various socio economic, demographic, physical accessibility and community related factors influence the women’s decision to use institutional delivery services [10–17]. In Ethiopia prior studies have been done to identify the socio-economic and demographic factors that influence institutional delivery service utilization [18–22]. Though institutional delivery services are affected by factors operating at different levels including the community contextual effects [11, 15–17, 23–25], none of the studies have tried to look at the factors that affect institutional delivery service utilization at individual and community levels simultaneously.

Hence, this study aimed to examine the individual and community level factors associated with institutional delivery simultaneously with the application of multilevel modeling and provide evidence for policy makers to better understand potential factors affecting institutional delivery.

Methods

Data source

The analysis was based on the 2011 Ethiopian demographic and health survey (EDHS) data. Approval letter for the use of this data was gained from the Measure DHS and the data set was downloaded from the Measure DHS website www.meauredhs.com. The survey covered all the nine regions and two city administrations of Ethiopia and participants were selected through a stratified two stage cluster sampling technique. The full details of the methods and procedures used in data collection in the EDHS have been published elsewhere [7]. The survey collected information from a nationally representative sample of 16,515 women aged 15–49 years. The study populations for this study were 7757 women who had at least one live birth in the 5 years preceding the survey, nested with in 595 communities across the country.

Study variables

Outcome variable

The main outcome variable in this study was whether a women had institutional delivery for the most recent live birth or not. It is a binary variable categorized as Yes or No.

Explanatory variables

These are individual level factors (age group of women, marital status, religion, women education, and husband education, sex of house hold head, health care decision, household wealth index, media exposure, birth order and ANC visit) and community level factors (region, place of residence, distance to health facility, community poverty, community women’s education, community media exposure and Community ANC utilization rate). The aggregate community level explanatory variables were constructed by aggregating individual level characteristics at the community (cluster) level and categorization of the aggregate variables was done as high or low based on the distribution of the proportion values calculated for each community. Histogram was used to check the distribution of the proportion values. If the aggregate variable was normally distributed mean value and if not normally distributed median value was used as cut off point for the categorization (Community poverty was categorized as high if the proportion of women from the two lowest wealth quintiles in a given community was 47–100 % and low if the proportion was 0–46 %, Community media exposure was categorized as low if the proportion of women exposed to media in the community was 0–15 % and categorized as high if the proportion was 16–100 %, Community education was categorized as low if the proportion of women with secondary education & above in the community was 0 % and categorized as high if the proportion was 1–100 % and Community ANC utilization rate was categorised as low if the proportion of women who attended at least one ANC visit in the community was 0–45 % and categorized as high if the proportion was between 46 and 100 %.

Data analysis

A multi level logistic regression analysis technique was employed in this study in order to account for the hierarchal structure of the DHS data and the binary response of the outcome variable [26–28].

Bivariate multilevel logistic regression analysis was performed to estimate the crude odds ratios at 95 % confidence interval and those variables which were statistically significant were considered in the multivariate analysis. Finally, multivariate multilevel logistic regression analysis was performed to estimate the adjusted odds ratios and to estimate the extent of random variations between communities.

Model building

Four models containing variables of interest were fitted using the xtmelogit command in STATA version 11.0.

Model I (Empty model) was fitted without explanatory variables to test random variability in the intercept and to estimate the intra class correlation coefficient (ICC). Model II examined the effects of individual level characteristics, Model III examined the effect of community level variables and Model IV examined the effects of both individual and community level characteristics simultaneously.

The final two level model in which the individual women (level 1) were nested within the community (level 2) was expressed elsewhere [26].

Since the models were nested, the Chi square likelihood-ratio test was used to assess the difference between models. The p-values were estimated using the Wald statistics and a p value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Parameter estimation methods

In the multilevel models, the fixed effects (measures of association) estimates the association between the likelihood of institutional delivery and the individual and community level factors and were expressed as odds ratio with their 95 % confidence intervals. The random effects are the measures of variation in institutional delivery across communities expressed as ICC and proportional change in variance (PCV). The ICC was calculated to evaluate whether the variation in institutional delivery is primarily within or between communities [29, 30].

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from the ethical review committee of the college of health sciences of Mekelle University and also approval letter for the use of the EDHS data set was gained from the Measure DHS (ORC MACRO). No information obtained from the data set was disclosed to any third person.

Results

In this study, a total of 7757 women with their most recent birth in the 5 years prior to the survey were included in the analysis. Among the total women whose data were analyzed 49 % were aged 25–34 years, almost 67 % were uneducated, 29 % were from poorest households and the vast majority (80 %) resides in rural areas (See Tables 1, 2).

Multilevel logistic regression analysis

The fixed effects (measure of association) and the random intercepts for the use of institutional delivery services are presented in Table 3. The results of the empty model (Model I) depicted that there was a statistically significant variability in the odds of institutional delivery service utilization between communities (τ = 10.246, p-value = 0.000). Similarly, the ICC in the empty model implied that 75.6 % of the total variance in the utilization of institutional delivery services was attributed to differences between communities. In Model II only individual level variables were added. The results showed that women education level, husband educational level, household wealth index, media exposure, birth order and antenatal care visits were significantly associated with birth at health institutions. The ICC in Model II indicated that, 25.3 % of the variation in women’s institutional delivery service utilization was attributable to differences across communities. As shown by the PCV, 89.1 % of the variance in institutional delivery service utilization across communities was explained by the individual level characteristics. In Model III only community level variables were added. The result revealed that women from urban areas, residing in communities with low poverty level, residing in communities with high media exposure and women residing in communities with high rate of antenatal care utilization were significantly associated with institutional delivery. The ICC in Model III implied that differences between communities account for about 19 % of the variation in women’s institutional delivery service utilization. In addition, the PCV indicated that 92.4 % of the variation in institutional delivery service utilization between communities was explained by community level characteristics.

Model IV, the final model included both the individual and community level characteristics simultaneously. After controlling for other individual and community level factors, women who had primary education were 50 % (AOR = 1.50; 95 % CI 1.202–1.880) and women who had secondary education and above were 3.6 times (AOR = 3.60; 95 % CI 2.491–5.214) more likely to give birth at health institutions as compared to women who had no education. Regarding media exposure, women who had media exposure were 39 % more likely (AOR = 1.39; 95 % CI 1.115–1.752) to give birth at health institutions compared to women who had no media exposure. After holding other factors constant, women from richest households had 74 % higher (AOR = 1.74; 95 % CI 1.143–2.648) odds of institutional delivery as compared to women from poorest households. Looking at birth order, women with birth order of two to three were 51 % (AOR = 0.49; 95 % CI 0.385–0.622); women with birth order of four to five were 62 % (AOR = 0.38; 95 % CI 0.286–0.512) and women with birth order of six and above were 77 % (AOR = 0.33; 95 % CI 0.245–0.456) less likely to give birth at health institutions compared to women who had first order births. Women who had one ante natal care visit were 89 % (AOR = 1.89; 95 % CI 1.148–3.113) and woman who had two to three antenatal care visits were 2.7 times (AOR = 2.66; 95 % CI 2.031–3.479) more likely to give birth at health institutions compared to woman who had no antenatal care checkups. Similarly, women who had four and above antenatal care visits were 4.4 times more likely (AOR = 4.43; 95 % CI 3.405–5.751) to give birth at health institutions compared to women who had no antenatal care checkups.

Keeping other variables constant, women from urban areas were almost 4.7 times more likely (AOR = 4.74; 95 % CI 3.196–7.039) to give birth at health institutions compared to their rural counterparts. Women residing in communities with high proportion of educated women had 71 % higher (AOR = 1.71; 95 % CI 1.256–2.319) chance of institutional delivery as compared to women residing in communities with low proportion of educated women. Similarly, women residing in communities with high ANC utilization rate were 55 % more likely (AOR = 1.55; 95 % CI 1.132–2.127) to give birth at health institutions than women residing in communities with low ANC utilization rate.

After the inclusion of both the individual and community level variables in model IV, the variation in the odds of institutional delivery care between communities still remained statistically significant(τ = 0.613, p-value = 0.000). As shown by the estimated ICC, 15.7 % of the variability in institutional delivery service utilization was attributable to differences between communities. The PCV indicated that, 94.1 % of the variation in institutional delivery service utilization across communities was explained by both individual and community level factors included in model IV.

Discussion

This study was based on the data of 2011 Demographic and Health Survey conducted in Ethiopia. The study has identified several factors that have significant influence on the utilization of health institutions for child birth. The finding of this study showed that women education exerts a positive significant influence on the use of delivery care services. This result concurred with findings of several studies [14–22]. The possible explanation could be, educated women have a greater confidence and capabilities to take actions regarding their own health and have the ability and willingness to travel outside home to seek out modern and quality health care services. In addition, educated women have greater exposure in accessing relevant health information on maternal health services thus enabling them to seek proper medical care whenever necessary.

Results of this study verified that women from richest households had higher odds of institutional delivery than women from poorest households which corroborates the findings that have been reported in prior studies [10, 15–17, 31, 32]. The possible explanation could be related to the implicit costs needed to access health care services. Media exposure also affects institutional delivery positively which is consistent with the findings of other studies [33–35]. Another study in Ethiopia also indicated that knowledge of mothers on pregnancy and delivery services has a significant influence on institutional delivery [20]. This shows that access to health related information has a strong influence on institutional delivery. Literatures also documented that exposure to media is an important source for health information [12, 36] and promotes health related behavior of the women.

Pertaining to birth order, the findings of this study depicted that the odds of utilizing health institutions for delivery care decreases with an increase in child birth order. This corroborates with the findings of several studies [33–39]. A possible explanation is that, after the uneventful birth of the first child at home, subsequent deliveries are perceived to be of low risk, thus increasing the likelihood of delivering subsequent babies at home. Also, a higher birth order suggests a greater number of children in the house hold as a result of which the women might have greater responsibilities and less time to visit health facilities for delivery care.

This study also revealed that women who had at least one ANC visit for their recent birth have higher chance of institutional delivery than women who have no ANC visits. Previous studies [18–21, 32, 40–43] also reported that ANC attendance increases the likelihood of institutional delivery. ANC attendance could be a marker of familiarity of women to maternal health services. Analysis of DHS data from six African countries and a study in India have also shown that the characteristics that predispose women to seek pregnancy care also make them more likely to seek care during delivery [11, 37]. In addition, antenatal care could also be an opportunity for health workers to provide health information and to discuss on the women’s place of delivery. In a study conducted in Tanzania, women informed about pregnancy complications during antenatal care were found to be more likely to deliver at a health facility [44]. This shows that the information given to pregnant women during antenatal care is vital to promote institutional delivery service.

In this study, geographical region where a woman resides was found to be an important predictor of institutional delivery. Other studies conducted in developing countries also pointed out the significant regional variations in the use of health facilities for delivery care [15–17, 39, 45–47]. Urban residence was also found to have a positive significant association with institutional delivery. This result is in agreement with studies conducted in developing countries [24, 36, 39, 41, 48–51]. The importance of place of residence in determining women’s use of health institutions for child birth can be explained through the availability of health services. As explained by another study, urban women in Ethiopia tend to benefit from increased knowledge and access to maternal health services [10]. Another study also indicated that rural areas generally have poor infrastructure, fewer health facilities and inadequate health services compared to urban areas, making women from rural areas less likely to utilize health facilities for delivery care [12]. Moreover, women from urban areas might have higher receptivity to new health related information and familiar with modern health care.

In this study distance to health facility was negatively associated with institutional delivery service utilization. A study conducted in Tanzania also found similar results where longer distance to health facility was related to home delivery [44]. This finding is also in agreement with the results of several studies in developing countries where physical proximity to health facilities plays an important role in the utilization of delivery services [40, 52–59]. The effect of distance on the use of health services has been attributed to the time and cost of travel and poor road conditions which reduces health seeking behavior and become an actual obstacle to access health care after an individual has decided to seek care [54, 60].

This study also found that community women’s education increases the odds of institutional delivery which is similar with a study done in six African countries [11]. Women residing in communities with high antenatal care utilization rate were also found to have higher chance of institutional delivery than women residing in communities with low rate of antenatal care utilization. This finding corroborates with a study in Congo [16]. The high ANC utilization rate at community level may reflect the familiarity of the community about maternal health services and the health service use habits of women in the community which plays an important role in influencing other women’s health seeking behavior positively. Data were not present to measure the actual presence of health services, so this variable may be acting as a proxy for service availability. As a result, higher ANC utilization at the community level might show the availability of maternal health services particularly delivery services in the community.

As hypothesized, results of this study showed that community level random intercepts (variances) were large and statistically significant indicating considerable differences between communities in the propensity of women’s use of health institutions for delivery services. This supports the application of multilevel modeling for this particular study [26–29].

This study also indicated the presence of significant unobserved variations between communities beyond the influence of the measured individual and community factors. Studies conducted in Nigeria, Congo, Indonesia and six African countries also found similar findings with a significant unobserved variability in the odds of institutional delivery across communities [11, 15–17]. The unobserved effects might represent the differences among communities in terms of social norms, cultural beliefs and health service related factors like quality of health services which influences people’s attitudes and opinions towards delivery care services.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The study was based on the most recent EDHS with a nationally representative large sample size. In addition, this study applied multilevel modeling to accommodate the hierarchical nature of the EDHS data. Despite the above strengths, the study has the following limitations. There might be recall bias given that the events took place 5 years preceding the survey. The data could have been more useful to this study if some particular information on service related factors like service availability and quality of health services had been collected.

Conclusion and recommendations

In this study both the individual and community level characteristics were found to have significant influence on institutional delivery. Women’s education, household socio economic level, media exposure, birth order and ante natal care visit were the factors that influence institutional delivery at the individual level. The study also showed that the communities in which the women reside play a significant role in shaping a women’s decision to utilize health institutions for delivery services. Among the community characteristics place of residence, region where the women reside, distance to health facility, community women’s education and community ANC utilization rate were the factors found to be significantly associated with institutional delivery. Further researches of these factors are needed to better understand how these factors may affect the decision to seek institutional delivery.

Abbreviations

- ANC:

-

ante natal care

- AOR:

-

adjusted odds ratio

- CSA:

-

Central Statistical Agency

- EDHS:

-

Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey

- FMOH:

-

Federal Ministry of Health

- ICC:

-

intra class correlation coefficient

- MM:

-

maternal mortality

- PCV:

-

proportional change in variance

- UNFPA:

-

United Nation Fund for Population Affairs

- UNICEF:

-

United Nations Children’s Fund

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

World Health Organization. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2010 estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA and the World Bank; 2012.

United Nations. The Millennium development goals report. New York; 2012.

World Health Organization. Maternal mortality, May 2012. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs348/en/index.html. Accessed 1 Feb 2013.

UNFPA. Skilled attendance at birth, 2012. http://www.unfpa.org/public/mothers/pid/4383. Accessed 1 Feb 2013.

World Health Organization. PMNCH fact sheet on maternal mortality. Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 5; 2011.

World Health Organization. Proportion of births attended by a skilled health worker 2008 updates. WHO Geneva; 2008.

CSA and ORC Macro. Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2011. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland, USA; 2012.

FMOH, Ethiopia. Health Sector Development Program IV 2010/11–2014/15; 2010.

FMOH, Ethiopia. Health Sector Development Program IV annual performance report; 2011/2012.

Mekonnen Y, Mekonnen A. Factors influencing the use of maternal healthcare services in Ethiopia. J Health Popul Nutr. 2003;21(4):374–82.

Stephenson R, Baschieri A, Clements S, Hennink M, Madise N. Contextual influences on the use of health facilities for childbirth in Africa. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(1):84–93.

Gabrysch S, Campbell O. Still too far to walk: Literature review of the determinants of delivery service use. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:34. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-9-34.

Montagu D, Yamey G, Visconti A, Harding A, Yoong J. Where do poor women in developing countries give birth? A multi country analysis of demographic and health survey data. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e17155. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017155.

Thind A, Mohani A, Banerjee K, Hagigi F. Where to deliver? Analysis of choice of delivery location from a national survey in India. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:29. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-8-29.

Aremu O, Lawoko S, Dalal K. Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage, individual wealth status and patterns of delivery care utilization in Nigeria: a multilevel discrete choice analysis. Int J Women’s Health. 2011;3:167–74.

Aremu O, Lawoko S, Dalal K. The influence of individual and contextual socioeconomic status on obstetric care utilization in the Democratic Republic of Congo: a population based study. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3(4):278–85.

Babalola S, Fatusi A. Determinants of use of maternal health services in Nigeria—looking beyond individual and household factors. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:43. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-9-43.

Mulumebet A, Abebe G, Tefera B. Predictors of safe delivery service utilization in Arsi zone, South-East Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2011;21(special issue):95–106.

Gurmesa T, Abebe G. Safe delivery service utilization in Metekel zone, North West Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2008;17(4):213–22.

Alemayehu S, Fekadu M, Solomon M. Institutional delivery service utilization and associated factors among mothers who gave birth in the last 12 months in Sekela District, North West of Ethiopia. A community based cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:74. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-12-74.

Abdella A, Abebaw G, Zelalem B. Institutional delivery service utilization in Munisa Woreda, South East Ethiopia. A community based cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:105.

Worku A, Jemal M, Gedefaw A. Institutional delivery service utilization in Woldia, Ethiopia. Sci J Public Health. 2013;1(1):18–23.

Kesterton A, Cleland J, Sloggett A, Ronsmans C. Institutional delivery in rural India: the relative importance of accessibility and economic status. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010;10:6–8.

Jat T, Ng N, Sebastian M. Factors affecting the use of maternal health services in Madhya Pradesh state of India: a multilevel analysis. Int J Equity Health. 2011;10:59.

Kruk M, Rockers P, Mbaruku G, Paczkowski M, Galea S. Community and health system factors associated with facility delivery in rural Tanzania: a multilevel analysis. Health Policy. 2010;97(2):209–16.

Goldstein H. Multilevel statistical models. UK: University of Bristol; 2011. p. 1–21.

Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A. Multilevel and longitudinal modeling using Stata. Texas, USA; 2008. p. 109–98.

Hox J. Multilevel analysis techniques and applications. The Netherlands: Utrecht University; 2010.

Snijders T, Bosker R. Multilevel analysis: an introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. London, UK; 2003. p. 223–6.

Merlo J, Yang M, Chaix B, Lynch J, Ra˚stam L. A brief conceptual tutorial on multilevel analysis in social epidemiology: investigating contextual phenomena in different groups of people. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2005;59:729–36. doi:10.1136/jech.2004.023929.

Ahmed S, Creanga A, Gillespie D, Tsui A. Economic status, education and empowerment: implications for maternal health service utilization in developing countries. PLoS One. 2010;5(6):e11190. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011190.

Muchabaiwa L, Mazambani D, Chigusiwa L, Bindu S, Mudavanhu V. Determinants of maternal healthcare utilization in Zimbabwe. Int J Econ Sci Appl Res. 2012;5(2):145–62.

Agha S, Carton T. Determinants of institutional delivery in rural Jhang, Pakistan. Int J Equity Health. 2011;10:31.

Begum H, Sayem A, Nili N. Differentials in place of delivery and delivery assistance in urban slum areas, Bangladesh. J Fam Reprod Health. 2012;6(2):49–58.

Mahapatro S. Utilization of maternal and child health care services in India: does women’s autonomy matter? J Fam Welf. 2012;58(1):22–33.

Amponsah E, Moses I. Expectant mothers and the demand for institutional delivery: do household income and access to health information matter? Some insight from Ghana. Eur J Soc Sci. 2009;8(3):469–82.

Nair M, Ariana P, Webster P. What influences the decision to undergo institutional delivery by skilled birth attendants? A cohort study in rural Andhra Pradesh, India. Int Electron J Rural Remote Health Res. 2012;12:5–9.

Saini S, Walia I. Trends in place of delivery among low income community in a resettled colony Chandigarh India. Nurs Midwifery Res J. 2009;5(4):133–41.

Kamal S. Preference for institutional delivery and caesarean sections in Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr. 2013;31(1):96–109.

Lwelamira J, Safari J. Choice of place for childbirth: prevalence and determinants of health facility delivery among women in Bahi District, Central Tanzania. Asian J Med Sci. 2012;4(3):105–12.

Kabakyenga J, Ostergren P, Turyakira E, Pettersson K. Influence of birth preparedness, decision-making on location of birth and assistance by skilled birth attendants among women in South Western Uganda. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35747. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0035747.

Barber S. Does the quality of prenatal care matter in promoting skilled institutional delivery? A study in rural Mexico. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10(5):419–25.

Hadi A, Rahman T, Khuram D, Ahmed J, Alam A. Raising institutional delivery in war-torn communities: experience of BRAC in Afghanistan. Asia Pac J Fam Med. 2007;6(1):5–7.

Mpembeni R, Killewo J, Leshabari M, Massawe S, Jahn A, Mushi D, Mwakipa H. Use pattern of maternal health services and determinants of skilled care during delivery in Southern Tanzania: implications for achievement of MDG-5 targets. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2007;7:29. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-7-29.

Utomo B, Sucahya P, Utami F. Priorities and realities: addressing the rich–poor gaps in health status and service access in Indonesia. Int J Equity Health. 2011;10:47.

Pardeshi G, Dalvi S, Pergulwar C, Gite R, Wanje S. Trends in choosing place of delivery and assistance during delivery in Nanded District, Maharashtra, India. J Health Popul Nutr. 2011;29(1):71–6.

Palamuleni M. Determinants of non-institutional deliveries in Malawi. Malawi Med J. 2013;3:981–3.

Addis Alem F, Meaza D. Prevalence of institutional delivery and associated factors in Dodota Woreda (district), Oromiya regional state, Ethiopia. BMC Reprod Health. 2012;9:33.

Sharma S, Sawangdee Y, Sirirassamee B. Access to health: women’s status and utilization of maternal health services in Nepal. J Biosoc Sci. 2007;39(5):671–92.

Johnson F, Padmadas S, Brown J. On the spatial inequalities of institutional versus home births in Ghana: a multilevel analysis. J Commun Health. 2009;34(1):64–72.

Henry V, Dahiru T. Utilization of non-skilled birth attendants in Northern Nigeria: a rough terrain to the health-related MDGs. Afr J Reprod Health. 2010;14(2):36–45.

Varma D, Khan M, Hazra A. Increasing institutional delivery and access to emergency obstetric care services in Rural Uttar Pradesh. J Fam Welf. 2010;56:23–30.

Danforth E, Kruk M, Rockers P, Mbaruku G, Galea S. Household decision-making about delivery in health facilities: evidence from Tanzania. J Health Popul Nutr. 2009;27(5):696–703.

Stekelenburg J, Kyanamina S, Mukelabai M, Wolffers I, Roosmalen J. Waiting too long: low use of maternal health services in Kalabo, Zambia. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9(3):390–8.

Joharifard S, Rulisa S, Niyonkuru F, Weinhold A, Sayinzoga F, Wilkinson J, Ostermann J, Thielman N. Prevalence and predictors of giving birth in health facilities in Bugesera District, Rwanda. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:7–9.

Moore B, Alex H, George I. Utilization of health care services by pregnant mothers during delivery: a community based study in Nigeria. J Med Med Sci. 2011;2(5):864–7.

Allegri M, Ridde V, Louis V, Sarker M, Tiendrebéogo J, Yé M, Müller O, Jahn A. Determinants of utilisation of maternal care services after the reduction of user fees: a case study from rural Burkina Faso. Health Policy. 2010;. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.10.010.

Adei D, Fiscian Y, Ephraim L, Diko S. Access to maternal health care services in the Cape Coast Metropolitan Area, Ghana. Curr Res J Soc Sci. 2012;4(1):12–20.

Gabrysch S, Cousens S, Cox J, Campbell O. The influence of distance and level of care on delivery place in rural Zambia: a study of linked national data in a geographic information system. PLoS Med. 2011;8(1):e1000394. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000394.

Kruk M, Paczkowski M, Mbaruku G, Pinho H, Galea S. Women’s preferences for place of delivery in rural Tanzania: a population-based discrete choice experiment. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(9):1666–72.

Authors’ contributions

ZM: Initiated the research, wrote the research proposal, carried out the data analysis, interpreted the results and drafted the manuscript. WL, TG and SA: Involved in designing the study, revising the proposal, guiding the statistical analysis and write up of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the ICF International for Granting access to the use of the 2011 EDHS data for this study. We are also very grateful to Mekelle University College of public health, Tulane International Ethiopia and Federal Ministry of Health for their financial support and kind assistance during the entire process of the study.

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Competing interests The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Mekonnen, Z.A., Lerebo, W.T., Gebrehiwot, T.G. et al. Multilevel analysis of individual and community level factors associated with institutional delivery in Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes 8, 376 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1343-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1343-1