Abstract

Background

Feline babesiosis, sporadically reported from various countries, is of major clinical significance in South Africa, particularly in certain coastal areas. Babesia felis, B. leo, B. lengau and B. microti have been reported from domestic cats in South Africa. Blood specimens from domestic cats (n = 18) showing clinical signs consistent with feline babesiosis and confirmed to harbour Babesia spp. piroplasms by microscopy of blood smears and/or reverse line blot (RLB) hybridization were further investigated. Twelve of the RLB-positive specimens had reacted with the Babesia genus-specific probe only, which would suggest the presence of a novel or previously undescribed Babesia species. The aim of this study was to characterise these organisms using 18S rRNA gene sequence analysis.

Results

The parasite 18S rRNA gene was cloned and sequenced from genomic DNA from blood samples. Assembled sequences were used to construct similarity matrices and phylogenetic relationships with known Babesia spp. Fifty-five 18S rRNA gene sequences were obtained. Sequences from 6 cats were most closely related to published B. felis sequences (99–100% sequence identity), while sequences from 5 cats were most closely related to B. leo sequences (99–100% sequence identity). One of these was the first record of B. leo in Mozambique. One sequence had 100% sequence identity with the published B. microti Otsu strain. The most significant finding was that sequences from 7 cats constituted a novel Babesia group with 96% identity to Babesia spp. previously recorded from a maned wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus), a raccoon (Procyon lotor) from the USA and feral raccoons from Japan, as well as from ticks collected from dogs in Japan.

Conclusions

Babesia leo was unambiguously linked to babesiosis in cats. Our results indicate the presence of a novel potentially pathogenic Babesia sp. in felids in South Africa, which is not closely related to B. felis, B. lengau and B. leo, the species known to be pathogenic to cats in South Africa. Due to the lack of an appropriate type-specimen, we refrain from describing a new species but refer to the novel organism as Babesia sp. cat Western Cape.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Domestication of cats occurred in the Near East, probably by natural selection, the ancestor being the local feline subspecies, Felis silvestris lybica [1]. From here, domestic cats (Felis silvestris catus) have spread world-wide with a current total population of kept or feral cats estimated at nearly one billion [2]. With the exception of Australia, all inhabited continents also harbour indigenous felid species from which pathogens could conceivably be transferred to domestic cats. Feline babesiosis may be a case in point. Although cases of cats showing clinical signs of babesiosis have been reported sporadically from various countries, feline babesiosis seems to be an important disease of domestic cats only in South Africa, especially along the eastern and southern seaboard and with a few foci on the eastern escarpment [3, 4].

Babesia felis was described from a c.3-month-old wild-caught Sudanese wild cat (Felis ocreata, presumably a synonym of a F. silvestris subspecies) that was observed for 12 months but showed no overt clinical signs of disease [5]. Parasitaemia, initially 0.5%, soon peaked at 8% (possibly due to stress while the host was adapting to captivity), but gradually decreased over a 3-month period and subsequently fluctuated around 0.4%. Blood from this cat was inoculated into 22 domestic cats. None of these cats showed any overt clinical signs of disease, but all developed a parasitaemia not exceeding 1% initially and then decreasing to a fluctuating low level which persisted indefinitely [5]. Following the classification suggested by Wenyon [6], Davis [5] assigned the novel parasite to the genus Babesia; he did not designate and deposit a type-specimen, however, which led to subsequent confusion.

During the 1930s domestic cats exhibiting clinical signs similar to those of canine babesiosis, i.e. anaemia, icterus and lethargy, were occasionally presented to veterinarians in South Africa, especially in the Western Cape Province [7, 8]. Felis caffra, presumably the local subspecies of F. silvestris, was suspected as being a reservoir host [8]. In the index case report of feline babesiosis [7], the piroplasms seen on blood smears met the description of B. felis piroplasms by Davis [5]. Due to its pathogenicity in domestic cats, in contrast to B. felis (sensu stricto), Jackson et al. [7] proposed the name Nuttalia felis var. domestica for the South African organism. Choosing Nuttalia rather than Babesia as genus name, they followed Carpano et al. [9] in preferring the classification by Du Toit [10] rather than that of Wenyon [6].

Regrettably, Jackson’s [7] conclusion that the South African organism represented a distinct taxon to B. felis (s.s.), being at least a local variety of the latter, was overlooked in subsequent reports on clinical manifestation and treatment of feline babesiosis: the causative organism was merely referred to as B. felis [11,12,13]. This was also the name used when details of molecular characterisation of the Babesia sp. causing disease in cats were deposited in the GenBank database [14]. The matter will only be resolved if Davis’s [5] original specimens are traced, which seems unlikely. Molecular characterisation has since revealed the presence of B. felis (sensu lato) in cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus), lions (Panthera leo) and servals (Leptailurus serval) in South Africa, Namibia and Zambia [15, 16].

Domestic cats can also be infected with other Babesia spp. A large, unidentified Babesia was incriminated in causing severe clinical signs in a domestic cat in Harare, Zimbabwe [17]. When examining blood smears of sick cats in South Africa, veterinarians occasionally report finding large organisms (Fig. 1), resembling Babesia rossi of dogs rather than the small B. felis (s.l.) (Figs. 2, 3); attempts at identifying these organisms were unsuccessful (pers. obs.). Babesia canis subsp. presentii was described from two cats in Israel, one a subclinical carrier and the other suffering from co-infection of various other pathogens [18].

Babesia pantherae, a large piroplasm isolated from leopards (Panthera pardus) in Kenya and B. herpailuri isolated from a jaguarundi (Herpailurus yaguarondi) originating from Venezuela could be established in domestic cats [19,20,21]. In both cases overt clinical signs developed only in asplenic cats; spleen-intact cats developed a long-lasting parasitaemia but remained asymptomatic [19]. Unfortunately, this was before the advent of molecular characterisation of piroplasms.

A previous South African survey of cats with clinical signs consistent with babesiosis suggested the presence of further potentially pathogenic piroplasms [15]. Subsequent molecular characterisation revealed that the pathogen involved in two fatal cases of feline babesiosis, one being the first record of cerebral babesiosis in a domestic cat, showed a high similarity with B. lengau, previously described from asymptomatic cheetahs [22, 23].

The aim of the present study was to characterise piroplasms from domestic cats in South Africa (Western Cape and KwaZulu-Natal) and Mozambique (Maputo) exhibiting clinical signs of babesiosis, using 18S rRNA gene sequence data and phylogenetic analysis.

Methods

Blood samples from 18 domestic cats, submitted for diagnostic purposes by private veterinary practitioners to the Department of Veterinary Tropical Diseases, Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Pretoria, were included in the study (Table 1). Inclusion criteria were clinical signs of babesiosis, identification of piroplasms on blood smears and/or positive reverse line blot (RLB) hybridization assay results. Except for one specimen from Maputo, Mozambique, all samples originated from coastal areas in the Western Cape and KwaZulu-Natal provinces of South Africa (Fig. 4).

DNA was extracted according to the manufacturer’s instructions using the QIAamp® DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Whitehead Scientific, South Africa). The V4 hypervariable region of the parasite 18S rRNA gene was PCR amplified using Babesia and Theileria genus-specific primers RLB-F2 and biotin-labelled RLB-R2 [24, 25]; PCR reaction conditions were as described by Tembo et al. [26]. DNA extracted from blood from a known T. parva-infected buffalo [27] was used as a positive control, while PCR master mix without DNA was used as a negative control. A touch down thermal cycler programme was used to amplify the DNA [25]. The PCR products were then analysed using the RLB hybridization technique as previously described [24, 25, 28, 29]. Genus- and species-specific probes as described by Tembo et al. [26] were included on the membrane; in addition to this, a B. lengau probe [22] was also included.

The near full-length parasite 18S rRNA gene (~1700 bp) was PCR amplified using primers Nbab_1F [30] and TB Rev [31], as previously described by Bosman et al. [22]. Four separate reactions were prepared per sample. Amplicons of all four reactions per sample were pooled to avoid Taq polymerase-induced errors and purified using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Southern Cross Biotechnology, South Africa) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Nine of the samples (labelled BF; Table 1) that had been yielded positive RLB results in a previous study [15], were subjected to direct (bi-directional) sequencing on an ABI 3500XL genetic analyser using the amplification primers. For the other nine specimens, PCR amplicons were cloned prior to sequencing (in case of mixed infections not being detected or masked by the RLB assay) into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, Anatech, South Africa) and transformed into competent Escherichia coli JM109 cells (JM109 high-efficiency competent cells, Promega). Recombinant plasmids were directly (bi-directional) sequenced on the ABI 3500XL genetic analyser at Inqaba Biotechnical Industries using the vector primers SP6 and T7.

Sequences were assembled and edited using GAP 4 of the Staden package (Version 1.6.0 for Windows) [32]. A search for homologous sequences was performed using BLASTn [33]. The sequences were aligned with sequences of related genera from GenBank using ClustalX (Version 1.81 for Windows). Alignment files were also analysed with CLC Main Workbench version 4.0 (CLC bio, Aarhus, Denmark) to test consistency of the alignment. The alignment was manually truncated to the size of the smallest sequence (1421 bp). The genetic distances between the sequences were estimated by determining the number of nucleotide differences between sequences using MEGA version 7 [34]. Phylogenetic trees were constructed by the Neighbor-Joining (NJ) and Maximum Likelihood (ML) methods as implemented in MEGA 7. The two-parameter model of Kimura [35] was used to construct similarity matrices by single distance from the aligned sequence data; a NJ phylogenetic tree [36] was constructed in combination with the bootstrap method (1000 replicates/tree) [37]. The Hasegawa-Kishino-Yano (HKY + G + I) substitution model [38], determined as the best-fit model using MEGA 7, was used to infer a ML tree in combination with the bootstrap method (1000 replicates/tree) [37]. The 18S rDNA sequences of Cardiosporidium ciona (EU052685), the closest species for which data are available according to Schnittger et al. [39], was included as the outgroup. All consensus trees were edited using MEGA 7. The GenBank accession numbers of reference sequences used in this study are reported in Table 2. The 18S rRNA gene sequences obtained in this study were submitted to GenBank; the accession numbers are reported in Table 3.

Results

Clinical reports indicated that 15 cats showed severe clinical signs of babesiosis, e.g. lethargy, anaemia, icterus and fever. Although no detailed clinical reports were available for three cats (BF341, BF472 and BF455) (Table 1), the attending veterinarians had made tentative diagnoses of babesiosis. With the exception of one cat (BF272), organisms morphologically consistent with piroplasms were seen on microscopic examination of blood smears from 17 of the cats; seven of these had been reported as a “large” Babesia (Table 1).

The RLB hybridization assay results revealed that of the 13 samples tested, six (46.2%) tested positive for the presence of B. felis DNA. One of these samples (Cat02) had a mixed species infection with B. microti (Table 1). This was subsequently confirmed by cloning and sequencing analysis of the 18S rRNA gene. PCR amplicons from a further six samples (46.2%) hybridized with the Babesia genus-specific probe only, suggesting the presence of a potentially novel Babesia species. One sample (BF342) tested negative or below the detection limit of the assay although a large Babesia had been observed by microscopy.

A total of 55 nearly full-length (1484–1525 bp) parasite 18S rRNA gene sequences were obtained from the 18 samples. Of these, nine were directly sequenced and the rest were cloned prior to sequencing, yielding a further 46 sequences from the clones (Table 1). A BLASTn search revealed that sequences from six cats (two of from Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, and four from the Western Cape) were most closely related to a published 18S rRNA gene sequence of B. felis (AF244912) which was previously described from a domestic cat and caused severe clinical babesiosis in naturally and experimentally infected cats in South Africa [11, 13]. One of these 21 sequences (Cat06_A6) had 100% sequence identity to the published B. felis sequence, while the remaining sequences had 99% identity, differing by one nucleotide from the published B. felis 18S rRNA gene sequence over a 1525 bp region.

Sequences from four cats had 100% identity with published B. leo sequences, while one sequence (Cat07_5E) had 99% identity with B. leo (with a 3 nucleotide difference over a 1520 bp region). Babesia leo was previously described from lions in the Kruger National Park, South Africa, and was shown to be a distinct species from B. felis and other felid piroplasms [40]. One specimen was from Maputo, Mozambique, the other four being from KwaZulu-Natal, i.e. all on the north-eastern seaboard of southern Africa.

One sequence (Cat02new) had 98–100% sequence identity with published B. microti 18S rRNA gene sequences, including strains from the zoonotic B. microti lineages (USA, Munich, Kobe and Otsu/Hobetsu from Japan). It had 100% sequence identity to the published B. microti Otsu strain (AB119446) and differed by 3–6 nucleotides from the B. microti Gray (AY693840) and B. microti Munich (AB071177) strains, respectively.

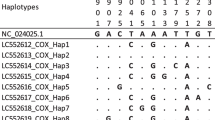

The most interesting finding, however, was that sequences obtained from seven cats, six from the Western Cape Province and one from Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, constituted a novel Babesia group with 96% identity to Babesia spp. previously described from captive maned wolves (Chrysocyon brachyurus) [41, 42], raccoons (Procyon lotor) from the USA [43] and Japan [44, 45] and from ticks collected from dogs in Japan [46]. Three genetic variants were identified within this novel Babesia group (designated “Novel Babesia sp. genetic variants 1, 2 and 3”), differing by 1 to 3 nucleotides from each other. Genetic variant 1 was found in five cats, variant 2 in three cats and variant 3 in two cats (Table 2). Three cats were infected with two genetic variants: two with variants 1 and 2, and one with variants 1 and 3.

The observed sequence similarities were subsequently confirmed by phylogenetic analyses. NJ and ML analyses were used to reveal the phylogenetic relationships between the near full-length 18S rRNA gene sequences obtained from this study to related Babesia species previously deposited in GenBank (Table 1). The topologies of both trees were similar. The ML tree is shown in Fig. 5. Three distinct clades, in concordance with Schnittger et al. [39], were obtained representing Clade I (including rodent-infecting B. microti and B. rodhaini, and feline-infecting B. leo and B. felis parasites), Clade II (including B. duncani isolated from humans, canine B. conradae and B. lengau described from cheetah in South Africa) and Clade VI (Babesia (s.s.), including the canine-infecting B. gibsoni, B. canis, B. rossi and B. vogeli, the human-infecting isolate B. venatorum, as well as species infecting ungulates (such as B. divergens and B. odocoilei) and recently described Babesia species infecting other carnivores such as bears, cougars and raccoons, as well as field rodents. The novel Babesia species identified in this study grouped within Clade VI, also referred to as the “carnivore/rodent clade” by Schnittger et al. [39].

Maximum likelihood tree showing the evolutionary relationships of the Babesia 18S rDNA sequences obtained, with published sequences. The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method based on the Hasegawa-Kishino-Yano model [38]. A discrete Gamma distribution was used to model evolutionary rate differences among sites [5 categories (+G, parameter = 0.4367)]. The rate variation model allowed for some sites to be evolutionarily invariable [(+I), 57.75% sites]. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 1208 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7 [34]

Discussion

The B. felis-positive specimens were from both the Western Cape (n = 4) and KwaZulu-Natal (n = 2). There is a single report of B. leo from a sick cat, but it was a mixed infection with B. felis [15]. The results of the present study unambiguously implicate B. leo in causing clinical babesiosis in domestic cats. The B. leo-positive specimens were all from the north-eastern seaboard of southern Africa: KwaZulu-Natal (n = 4) and Maputo, Mozambique (n = 1), which constituted the first record of B. leo from that country. The Kruger National Park, South Africa, from where B. leo was first described [40], has a 320-km-long border with Mozambique. In a direct line, the south-eastern tip of the Park is only c.70 km from Maputo.

Sequence and phylogenetic analysis of the 18S rRNA gene from seven cats showed that they harboured a novel Babesia sp. which segregated into three separate genetic variants in Babesia clade VI, the carnivore/rodent clade [39]. Babesia felis, B. leo and B. lengau, the three South African felid piroplasms hitherto known to cause clinical signs in domestic cats, were relatively closely related [15, 22, 40]. In contrast, the novel Babesia sp. reported here had only 92% sequence identity with B. felis (AF244912) and 89% sequence identity with B. leo (AF244911) and B. lengau (KC790443 and GQ411417), respectively. The 18S rRNA gene has been widely used to characterize and classify previously unknown Theileria and Babesia parasites [24, 25, 30, 47,48,49]. It has, however, not been established to what extent 18S rRNA gene sequences must differ for the source organisms to be considered different species, rather than merely a genetic variant or genotype within a species [50, 51]. A single gene tree does not necessarily reflect a species tree [39]; therefore, a tree should ideally be constructed using multiple genotypic characters of potentially different evolutionary histories [39].

The novel genetic variants reported here were most closely related (96% identity) to a novel Babesia sp. reported from culled feral raccoons from Japan [44, 45] and from a clinically affected juvenile raccoon from the USA [43]. It is tempting to speculate that feral raccoons may also have been the source of an incidental finding of this Babesia sp. in ticks collected from healthy dogs in Japan [46]. The same Babesia sp. was incriminated in causing severe clinical babesiosis in two South American maned wolves from the same zoological park in Kansas, USA [41, 42].

When examining blood smears, veterinarians described the novel genetic variants reported here as “large” babesias. This may be the elusive large Babesia reported from cats in southern Africa. The arbitrary classification of babesias as either “large” or “small” is not satisfactory, however. For instance, the abovementioned Babesia sp. from raccoons was reported to be closely related to B. odocoilei and B. divergens [44], both generally regarded as “large” species. Nevertheless, the mean length of the round, oval, amoeboid or piriform organisms was 3.13 ± 0.77 µm (range 1.25–4.8 µm) and the mean width was 2.5 ± 0.61 µm [45]. Round, oval and amoeboid forms are trophozoites, which can be expected to increase in size. For comparative purposes, measuring newly formed merozoites should give more consistent and reliable results.

Six of the seven specimens of the novel genetic variants were from a fairly restricted area in the Western Cape Province (Bellville, Cape Town and Paarl). The other case was from Durban, KwaZulu-Natal. No further information was known about the latter case, e.g. whether the cat may originally have come the Cape Town area. It may be possible that the natural hosts and/or vectors of these novel genetic variants are restricted to the Western Cape Province. Due to lacking an appropriate type specimen, we refrain from describing a new species but refer to the novel organism as Babesia sp. cat Western Cape.

Further characterisation of this novel organism is warranted to understand the pathogenesis and epidemiology, as well as to develop appropriate diagnostic markers. Obtaining appropriate specimens poses a challenge, however. Veterinarians in the feline babesiosis-endemic area usually confirm a diagnosis by finding piroplasms on a blood smear and then treat the cat. Blood specimens are only rarely submitted for confirmation of a diagnosis. Furthermore, our laboratory is in Pretoria, c.600 km from Durban and 1500 km from Cape Town, which hampers routine sampling of clinical cases.

Conclusions

Our results indicate the presence of a novel potentially pathogenic Babesia sp. in felids in South Africa, which is not closely related to Babesia felis, Babesia lengau and Babesia leo, the three species known to be pathogenic to cats. Due to the lack of an appropriate type-specimen, we refrain from describing and a new species but refer to the novel organism as Babesia sp. Cat Western Cape.

References

Driscoll CA, Menotti-Raymond M, Roca AL, Hupe K, Johnson WE, Geffen E, et al. The Near Eastern origin of cat domestication. Science. 2007;317:519–23.

Driscoll CA, Macdonald DW, O’Brien SJ. From wild animals to domestic pets, an evolutionary view of domestication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(Suppl. 1):9971–8.

Jacobson LS, Schoeman T, Lobetti RG. A survey of feline babesiosis in South Africa. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 2000;71:222–8.

Penzhorn BL, Stylianides E, Coetzee MA, Viljoen JM, Lewis BD. A focus of feline babesiosis at Kaapschehoop on the Mpumalanga escarpment. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 1999;70:60.

Davis LJ. On a piroplasm of the Sudanese wild cat (Felis ocreata). Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1929;12:523–33.

Wenyon CM. Protozoology. London: Baillière, Tindall & Cox; 1926.

Jackson C, Dunning FJ. Biliary fever (nuttaliosis) of the cat: a case in the Stellenbosch district. J S Afr Vet Med Assoc. 1937;8:83–7.

McNeil J. Piroplasmosis of the domestic cat. J S Afr Vet Med Assoc. 1937;8:88–90.

Du Toit PJ. Zur Systematik der·Piroplasmen. Arch Protist. 1918;39:81–104.

Carpano M. Sulle piroplasmi dei carnivori e su di un nuovo piroplasma de felini (Babesiella felis) nel puma: Felis concolor. Bollettino No. 137. Cairo: Serviz Tecn Scient Min Dell Agric.; 1934.

Futter GJ, Belonje PC. Studies on feline babesiosis. 2. Clinical findings. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 1980;51:143–6.

Potgieter FT. Chemotherapy of Babesia felis infection: efficacy of certain drugs. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 1980;51:289–93.

Penzhorn BL, Lewis BD, López-Rebollar LM, Swan GE. Screening of five drugs for efficacy against Babesia felis in experimentally infected cats. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 2000;71:53–7.

Benson DA, Cavanaugh M, Clark K, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Lipman DJ, Ostell J, et al. GenBank. Nucl Acids Res. 2013;41(Database issue):D36–42.

Bosman AM, Venter EH, Penzhorn BL. Occurrence of Babesia felis and Babesia leo in various wild felid species and domestic cats in southern Africa, based on reverse line blot analysis. Vet Parasitol. 2007;144:33–8.

Williams BM, Berentsen A, Shock BC, Teixiera M, Dunbar MR, Becker MS, et al. Prevalence and diversity of Babesia, Hepatozoon, Ehrlichia, and Bartonella in wild and domestic carnivores from Zambia, Africa. Parasitol Res. 2014;113:911–8.

Stewart CG, Hackett KJW, Collett MG. An unidentified Babesia of the domestic cat (Felis domesticus). J S Afr Vet Assoc. 1980;51:219–22.

Baneth G, Kenny MJ, Tasker S, Anug Y, Shkap V, Levy A, et al. Infection with a proposed new subspecies of Babesia canis, Babesia canis subsp. presentii, in domestic cats. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:99–105.

Dennig HK. Babesieninfektionen bei exotischer Katzen and die Bedeutung dieser Blutparasiten für die tierärtzliche Forschung. Acta Zool Pathol Antverpiensia. 1969;48:361–7.

Dennig HK, Brocklesby DW. Babesia pantherae sp. nov., a piroplasm of the leopard (Panthera pardus). Parasitology. 1972;64:525–32.

Dennig HK. Eine unbekannte Babesienart beim Jaguarundi (Herpailurus yaguarondi). Kleintierpraxis. 1967;12:146–50.

Bosman AM, Oosthuizen EC, Peirce MA, Venter EH, Penzhorn BL. Babesia lengau sp. nov., a novel Babesia species in cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus Schreber, 1775) populations in South Africa. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:2703–8.

Bosman AM, Oosthuizen MC, Venter EH, Steyl JC, Gous TA, Penzhorn BL. Babesia lengau associated with cerebral and haemolytic babesiosis in two domestic cats. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:128.

Nijhof AM, Penzhorn BL, Lynen G, Mollel JO, Morkel P, Bekker CPJ, et al. Babesia bicornis sp. nov. and Theileria bicornis sp. nov.: tick-borne parasites associated with mortality in the black rhinoceros. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:2249–54.

Nijhof AM, Pillay V, Steyl J, Prozesky L, Stoltsz WH, Lawrence JA, et al. Molecular characterization of Theileria species associated with mortalities in four species of African antelopes. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:5907–11.

Tembo S, Collins NE, Sibeko-Matjila KP, Troskie M, Vorster I, Byaruhanga C, et al. Occurrence of tick-borne haemoparasites in cattle in the Mungwi District, Northern Province, Zambia. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2018;9:707–17.

Sibeko KP, Oosthuizen MC, Collins NE, Geysen D, Rambritch NE, Latif AA, et al. Development and evaluation of a real-time polymerase chain reaction test for the detection of Theileria parva infections in Cape buffalo (Syncerus caffer) and cattle. Vet Parasitol. 2008;155:37–48.

Bekker CPJ, de Vos S, Taoufik A, Sparagano OAE, Jongejan F. Simultaneous detection of Anaplasma and Ehrlichia species in ruminants and detection of Ehrlichia ruminantium in Amblyomma variegatum ticks by reverse line blot hybridization. Vet Microbiol. 2000;89:223–38.

Gubbels J, De Vos A, Van Der Weide M, Viseras J, Schouls LM, De Vries E, et al. Simultaneous detection of bovine Theileria and Babesia species by reverse line blot hybridization. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1782–9.

Oosthuizen MC, Zweygardt E, Collins NE, Troskie M, Penzhorn BL. Identification of a novel Babesia sp. from sable antelope (Hippotragus niger Harris, 1838). Vet Parasitol. 2008;163:39–46.

Matjila PT, Leisewitz AL, Oosthuizen MC, Jongejan F, Penzhorn BL. Detection of Theileria species in dogs in South Africa. Vet Parasitol. 2008;157:34–40.

Staden R, Beal KF, Bonfield JK. The staden package, 1998. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;132:115–30.

Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–10.

Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–4.

Kimura M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol. 1980;16:111–20.

Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–25.

Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–91.

Hasegawa M, Kishino H, Yano T. Dating the human-ape split by a molecular clock of mitochondrial DNA. J Mol Evol. 1985;22:160–74.

Schnittger L, Rodriguez AE, Florin-Christensen M, Morrison DA. Babesia: a world emerging. Inf Gen Evol. 2012;12:1788–809.

Penzhorn BL, Kjemtrup AM, López-Rebollar LM, Conrad PA. Babesia leo n. sp. from lions in the Kruger National Park, South Africa, and its relation to other piroplasms. J Parasitol. 2001;87:881–5.

Phair K, Carpenter JW, Smee N, Myers CB, Pohlman LM. Severe anemia caused by babesiosis in a maned wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus). J Zoo Wildl Med. 2012;43:162–7.

Wasserkrug Naor A, Lindemann DM, Schreeg ME, Marr HS, Birkenheuer AJ, Carpenter JW, et al. Clinical, morphological, and molecular characterization of an undetermined Babesia species in a maned wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus). Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2019;10:124–6.

Birkenheuer AJ, Whittington J, Neel J, Large E, Barger A, Levy MG, et al. Molecular characterization of a Babesia species identified in a North American raccoon. J Wildl Dis. 2006;42:375–80.

Jinnai M, Kawabuchi-Kurata T, Tsuji M, Nakajima R, Fujisawa K, Nagata S, et al. Molecular evidence for the presence of new Babesia species in feral raccoons (Procyon lotor) in Hokkaido, Japan. Vet Parasitol. 2009;162:241–7.

Kawabuchi T, Tsuki M, Sado A, Matoba Y, Asakawa M, Ishihara C. Babesia microti-like parasites detected in feral raccoons (Procyon lotor) captured in Hokkaido, Japan. Jpn J Vet Med Sci. 2005;67:825–7.

Inokuma H, Yoshizaki Y, Shimada Y, Sakata Y, Okuda M, Onishi T. Epidemiological survey of Babesia species in Japan performed with specimens from ticks collected from dogs and detection of new Babesia DNA closely related to Babesia odocoilei and Babesia divergens DNA. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:3494–8.

Gubbels M, Hong Y, van der Weide M, Qi B, Nijman IS, Guangyuan L, et al. Molecular characterisation of the Theileria buffeli/orientalis group. Int J Parasitol. 2000;30:943–52.

Birkenheuer AJ, Levy MG, Breitschwerdt EB. Development and evaluation of a seminested PCR for detection and differentiation of Babesia gibsoni (Asian genotype) and B. canis DNA in canine blood samples. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:4172–7.

Schnittger L, Yin H, Gubbels MJ, Beyer D, Niemann S, Jongejan F, et al. Phylogeny of sheep and goat Theileria and Babesia parasites. Parasitol Res. 2003;91:398–406.

Chae JS, Allsopp BA, Waghela SD, Park JH, Kakuda T, Sugimoto C, et al. A study of the systematics of Theileria spp. based upon small-subunit ribosomal RNA gene sequences. Parasitol Res. 1999;85:877–83.

Allsopp MT, Allsopp BA. Molecular sequence evidence for the reclassification of some Babesia species. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006;1081:509–17.

Caccio SM, Antunovic B, Moretti A, Mangili V, Marinculic A, Slemenda SB, et al. Molecular characterisation of Babesia canis canis and Babesia canis vogeli from naturally infected European dogs. Vet Parasitol. 2002;106:285–92.

Kjemtrup AM, Wainwright K, Miller M, Penzhorn BL, Carreno RA. Babesia conradae, sp. nov., a small canine Babesia identified in California. Vet Parasitol. 2006;138:103–11.

Holman PJ. Comparative study of cervid Babesia isolates. Thesis, Veterinary Pathobiology, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA; 1994.

Kjemtrup AM, Thomford J, Robinson T, Conrad PA. Phylogenetic relationships of human and wildlife piroplasm isolates in the western United States inferred from the 18S nuclear small subunit RNA gene. Parasitology. 2000;120:487–93.

Criado-Fornelio A, Gonzalez-del-Rio MA, Buling-Sarana A, Barba-Carretero JC. Molecular characterization of a Babesia gibsoni isolate from a Spanish dog. Vet Parasitol. 2003;117:123–9.

Saito-Ito A, Dantrakool A, Kawai A, Shiota T. Survey of rodents and ticks in human babesiosis emergence area in Japan: first detection of Babesia microti-like parasites in Ixodes ovatus. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:2268–70.

Zahler M, Rinder H, Gothe R. Genotypic status of Babesia microti within the piroplasms. Parasitol Res. 2000;86:642–6.

Cornillot E, Hadj-Kaddour K, Dassouli A, Noel B, Ranwez V, Vacherie B, et al. Sequencing of the smallest Apicomplexan genome from the human pathogen Babesia microti. Nucl Acids Res. 2012;40:9102–14.

Holman PJ, Madeley J, Craig TM, Allsopp BA, Allsopp MT, Petrini KR, et al. Antigenic, phenotypic and molecular characterization confirms Babesia odocoilei isolated from three cervids. J Wildl Dis. 2000;36:518–30.

Ellis J, Hefford C, Baverstock PR, Dalrymple BP, Johnson AM. Ribosomal DNA sequence comparison of Babesia and Theileria. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;54:87–95.

Oyamada M, Davoust B, Boni M, Dereure J, Bucheton B, Hammad A, et al. Detection of Babesia canis rossi, B. canis vogeli, and Hepatozoon canis in dogs in a village of eastern Sudan by using a screening PCR and sequencing methodologies. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12:1343–6.

McDermid KR, Snyman A, Verreynne FJ, Carroll JP, Penzhorn BL, Yabsley MJ. Surveillance for viral and parasitic pathogens in a vulnerable African lion (Panthera leo) population in the northern Tuli Game Reserve, Botswana. J Wildl Dis. 2017;53:54–61.

Sun Y, Li SG, Jiang JF, Wang X, Zhang Y, Wang H, et al. Babesia venatorum infection in child, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:896–7.

Ciancio A, Scippa S, Finetti-Sialer M, De Candia A, Avallone B, De Vincentiis M. Redescription of Cardiosporidium cionae (Van Gaver and Stephan, 1907) (Apicomplexa: Piroplasmida), a plasmodial parasite of ascidian haemocytes. Eur J Protistol. 2008;44:181–96.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr Christiaan Labuschagne and Dr Antoinette van Schalkwyk (Inqaba Biotechnical Industries (Pty) Ltd, Pretoria, South Africa), for their assistance with the sequence analysis, and the veterinarians who submitted specimens for this study, especially Drs Remo Lobetti and Fred Reyers. Professor Melvyn Quan prepared Fig. 4. Publication of this paper has been sponsored by Bayer Animal Health in the framework of the 14th CVBD World Forum Symposium.

Funding

This research was supported financially by the National Research Foundation (NRF), South Africa (grant no 2069496 to BL Penzhorn and grant no. 76529 to MCO).

Availability of data and materials

Data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article. The newly generated sequences were submitted to the GenBank database under the accession numbers provided in Table 2.

Authors’ contributions

AMB screened the samples with the reverse line blot, carried out the molecular genetic studies, participated in the sequence alignment and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. BLP coordinated the investigation, conducted literature searches and reviewed and edited all drafts of the manuscript. KAB co-supervised the project, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. TS handled clinical cases and collected most of the specimens. MCO supervised the laboratory work and sequence alignments, constructed the phylogenetic trees, reviewed all drafts of the paper and phylogenetic results and wrote the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the University of Pretoria (ref V116-15) and by the Research Committee of the Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Pretoria (ref 36-5-613). The South African Department of Agriculture, Forestry & Fisheries granted permission to do research in terms of Section 20 of the Animal Diseases Act, 1984 (Act no. 35 of 1984) (ref 12/11/1/1).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Bosman, AM., Penzhorn, B.L., Brayton, K.A. et al. A novel Babesia sp. associated with clinical signs of babesiosis in domestic cats in South Africa. Parasites Vectors 12, 138 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-019-3395-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-019-3395-x