Abstract

Background

Piroplasms are unicellular, tick-borne parasites. Among them, during the past decade, an increasing diversity of Babesia spp. has been reported from wild carnivores. On the other hand, despite the known contact of domestic and wild carnivores (e.g. during hunting), and a number of ixodid tick species they share, data on the infection of dogs with babesiae from other families of carnivores are rare.

Methods

In this study blood samples were collected from 90 dogs and five road-killed badgers. Ticks were also removed from these animals. The DNA was extracted from all blood samples, and from 33 ticks of badgers, followed by molecular analysis for piroplasms with PCR and sequencing, as well as by phylogenetic comparison of detected genotypes with piroplasms infecting carnivores.

Results

Eleven of 90 blood DNA extracts from dogs, and all five samples from badgers were PCR-positive for piroplasms. In addition to the presence of B. canis DNA in five dogs, sequencing identified the DNA of badger-associated “Babesia sp. Meles-Hu1” in six dogs and in all five badgers. The DNA of “Babesia sp. Meles-Hu1” occurred significantly more frequently in dogs often taken to forests (i.e. the preferred habitat of badgers in Hungary), than in dogs without this characteristic. Moreover, detection of DNA from this Babesia sp. was significantly associated with hunting dogs in comparison with dogs not used for hunting. Two PCR-positive dogs (in one of which the DNA of the badger-associated Babesia sp. was identified, whereas in the other the DNA of B. canis was present) showed clinical signs of babesiosis. Engorged specimens of both I. canisuga and I. hexagonus were collected from badgers with parasitaemia, but only I. canisuga contained the DNA of “Babesia sp. Meles-Hu1”. This means a significant association of the DNA from “Babesia sp. Meles-Hu1” with I. canisuga. Phylogenetically, “Babesia sp. Meles-Hu1” belonged to the “B. microti” group.

Conclusions

This is the first detection of the DNA from a badger-associated Babesia sp. in dogs, one of which also showed relevant clinical signs. Based on the number of dogs with blood samples containing the DNA of “Babesia sp. Meles-Hu1” in this study (i.e. exceeding the number of B. canis-positives), these findings should not be regarded as isolated cases. It is assumed that dogs, which are used for hunting or frequently visit forests, are more likely to be exposed to this piroplasm, probably as a consequence of infestation with I. canisuga from badgers or from the burrows of badgers. The above results suggest that “Babesia sp. Meles-Hu1” should be added to the range of piroplasms, which are naturally capable of infecting hosts from different families of Caniformia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Piroplasms (Apicomplexa: Piroplasmida) are unicellular, tick-borne parasites, which infect red and white blood cells of their vertebrate hosts [1]. Among them, Babesia spp. and Theileria spp. are the most significant from the veterinary point of view, in terms of both their geographical distribution and the range of affected host species.

In general, babesiae have long been regarded as host species-specific [2], but in the era of molecular biological methods the reported ranges of hosts susceptible to infection with a particular Babesia species have started to expand. When the currently known diversity of Babesia spp., infecting domestic carnivores as their typical hosts, is concerned, the number of relevant disease agents appears to be stable, despite the fact that during the past years the taxonomic rank and/or the naming of certain variants has changed or is still unresolved. Thus, in a worldwide context, dogs are susceptible to three species of the so-called large babesiae and three species of small babesiae [3].

However, an increasing diversity of Babesia spp. are reported from wild carnivores (e.g. in Japan: [4]), and the number of families within order Carnivora, in which piroplasms are molecularly detected, also increased (e.g. Ursidae [5, 6]; Herpestidae [7]; Hyaenidae [8]). Furthermore, mostly in individual cases, piroplasms from more distant host taxa might also occur in carnivores, as exemplified by T. equi or B. caballi in dogs (typical hosts being Equidae) [9, 10], or T. capreoli in grey wolves (typical hosts are Cervidae) [11]. Such occasional infections may even be associated with clinical signs in carnivores as “atypical hosts” [10].

These data highlight carnivores as a group important from the point of studying piroplasms, especially at the interface of domestic and wild carnivores, for which mutually infective Babesia spp. have been reported [12]. In the above context, the present study aimed to molecularly investigate piroplasms in a region of Hungary, where emerging tick species and tick-borne pathogens have been reported [13, 14]. To achieve this, blood samples and ticks were collected from dogs and badgers, consequently analyzed with PCR and sequencing.

Methods

Blood and tick samples were collected from dogs and European badgers (Meles meles) originating from 20 locations (17 and 3 for dogs and badgers, respectively) in southwestern Hungary (Somogy county) between March and October (dogs) and January to April (badgers) of 2017. From 90 dogs, EDTA-anticoagulated blood samples were drawn under clinical conditions (after skin surface sterilization, with sterile instruments) by cephalic venipuncture. The majority of sampled dogs (n = 80) were selected randomly (from regular patients of the Veterinary Clinic in Csurgó) and appeared to be healthy, but ten showed at least one clinical sign relevant to babesiosis. Animal data (owner, sex, age, mode of keeping) were recorded. From five freshly road-killed badgers EDTA-anticoagulated blood samples were collected (with sterile needle and syringe) from the heart, shortly after being reported to the Veterinary Authority. EDTA blood samples were frozen at -20 °C until further processing. In addition, ixodid ticks were removed from all animals with pointed tweezers then transferred into 96% ethanol for storage in separate vials according to host individuals. Tick species were identified according to standard keys [15], and ticks of the subgenus Pholeoixodes according to [16].

DNA was obtained using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instruction and using extraction controls to monitor cross contamination of samples in each run. DNA was extracted from 200 μl blood of 90 dogs and 5 badgers, as well as from 33 ticks collected from badgers. These ticks belonged to two species, i.e. Ixodes canisuga and I. hexagonus (subgenus Pholeoixodes), selected on the basis of literature data supporting their role in the transmission of Babesia spp. of the B. microti group [17, 18]. DNA was extracted from the ticks individually, with the same method as from the blood samples, but including an overnight digestion in tissue lysis buffer and proteinase-K at 56 °C, and incubation in lysis buffer for 10 min at 70 °C. DNA samples were finally taken up in 130 μl elution buffer.

DNA extracts from all 95 blood samples and 33 ticks were screened for the presence of piroplasms by a conventional PCR [19]. This PCR amplifies an approximately 500 bp fragment of the 18S rRNA gene of Babesia/Theileria spp. with the primers BJ1 (forward: 5′-GTC TTG TAA TTG GAA TGA TGG-3′) and BN2 (reverse: 5′-TAG TTT ATG GTT AGG ACT ACG-3′) [20]. The 25.0 μl final volume of reaction mixture contained 5.0 μl template DNA, 1.0 U HotStar Taq Plus DNA Polymerase (5U/μl) (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), 2.5 μl of 10× Coral Load PCR Buffer (15 mM MgCl2 included), 0.5 μl dNTP mix (10 mM), 0.5 μl of each primer (50 μM) and 15.8 μl distilled water. Cycling conditions consisted of an initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 54 °C for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 40 s. The final extension was performed at 72 °C for 5 min.

Each PCR was run with positive and negative controls (i.e. sequence-verified DNA of Babesia canis, and non-template reaction mixture, respectively). PCR products were visualized in 1.5% agarose gel. Negative controls and extraction controls remained PCR negative in all tests. Purification and sequencing (directly from the PCR product, using the forward primer and generating the sequence twice per sample) were performed from all piroplasm PCR-positive samples at Biomi Inc. (Gödöllő, Hungary). Sequences were aligned and compared to reference GenBank sequences by nucleotide BLASTn program (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). All blood samples, which yielded unusual results (i.e. the presence of DNA from a Babesia sp. not yet reported in the relevant host) were re-tested in duplicates, by repeating the whole procedure from the beginning (DNA extraction, PCR and sequencing). Representative sequences were submitted to the GenBank database under the accession numbers MG778912-MG778915. Phylogenetic analyses were performed with the Maximum Likelihood method and Tamura-Nei model, using MEGA 6.0.

Rates of PCR-positivity were compared with the Fisher’s exact test and differences were considered significant when P < 0.05.

Results

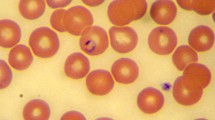

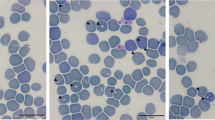

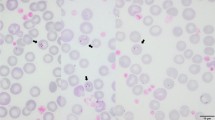

Among blood DNA extracts, 11 of 90 samples from dogs, and all five samples from badgers were PCR-positive for piroplasms. Sequencing identified two Babesia spp. in dogs. In six dog blood samples the DNA of a Babesia sp. was present, which was formerly reported from European badgers (Meles meles) in Hungary and designated as “Babesia sp. Meles-Hu1” (GenBank: KX218234). This genotype also corresponded to “Babesia sp. badger type-A” reported from Spain (GenBank: KT223484) and the UK (GenBank: KX528553), with 100% (472/472 bp) and 99.8% (471/472 bp) identity, respectively. In addition, the DNA of B. canis was detected in five blood samples from dogs: in one case corresponding to “genotype A” (430/430 bp; 100% identity with KP835549), and in four samples to “genotype B” (430/430 bp; 100% identity with KP835550) formerly reported in Hungary. In the blood of all badgers the DNA of “Babesia sp. Meles-Hu1” was present, which had 100% (472/472 bp) identity with the above dog isolate.

Concerning the distribution of Babesia species in dogs according to their mode of keeping, the DNA of “Babesia sp. Meles-Hu1” occurred significantly (P = 0.0001) more frequently in dogs often taken to forests (5 of 12) than in dogs without this characteristic (1 of 78) (Table 1). Moreover, the presence of DNA from this Babesia sp. was significantly (P = 0.00008) associated with hunting dogs (4 of 6 were infected) in comparison with dogs not used for hunting (2 of 84) (Table 1). Taking into account the sampling time, the dog samples containing the DNA of different Babesia spp. also showed an uneven seasonal distribution: while the DNA of “Babesia sp. Meles-Hu1” was detected in samples collected in March (n = 3) and August (n = 3), the DNA of B. canis was present in samples obtained in May (n = 2) or September (n = 3). Importantly, two PCR-positive dogs (one yielding the sequence of the badger-associated Babesia sp., the other that of B. canis) showed clinical signs of babesiosis (fatigue, renal failure and/or anaemia, icterus).

Altogether 19 ticks were collected from dogs, i.e. Dermacentor reticulatus (n = 10), Ixodes ricinus (n = 8) and I. hexagonus (n = 1); and 53 ticks from badgers, i.e. I. canisuga (n = 34), D. reticulatus (n = 7), I. hexagonus (n = 6), I. ricinus (n = 3), I. kaiseri (n = 2) and Haemaphysalis concinna (n = 1).

In the molecularly analyzed 33 Pholeoixodes tick samples, only the DNA of “Babesia sp. Meles-Hu1” was found. Interestingly, while engorged specimens of both I. canisuga (n = 27) and I. hexagonus (n = 6) were collected from badgers, which had this Babesia sp. in their blood (as shown above), none of the I. hexagonus specimens were PCR-positive, but 66.7% (18 of 27) of I. canisuga DNA extracts contained “Babesia sp. Meles-Hu1” (Table 1). This was a significant association of this piroplasm with I. canisuga (P = 0.0045).

Phylogenetically, sequences of B. canis genotypes amplified from dogs in the present study clustered with other conspecific isolates of the clade “Babesia (sensu stricto)” (Fig. 1). On the other hand, sequences of “Babesia sp. Meles-Hu1” obtained from both dogs and badgers here belonged to the “B. microti phylogenetic group” (Fig. 1).

Maximum Likelihood tree of piroplasm DNA sequences reported from carnivores, shown according to their families. Sequences from this study are highlighted with red color. Piroplasm categories are named after [1] (except for Theileria equi, Cytauxzoon spp. and Theileria spp. united in one group). For Hyaenidae, the sequence KF270649 had a short coverage and therefore is not included (but in a sequence comparison it aligned with B. lengau). Vertical red columns mark adjacent families of Caniformia. The scale-bar indicates the number of substitutions per site

Discussion

In this study, blood and tick samples collected from dogs and European badgers were molecularly analyzed for the presence of piroplasm DNA. The DNA from both B. canis and “Babesia sp. Meles-Hu1” were found. Based on literature reviews, in European badgers “Babesia sp. badger type-A” and “ Babesia sp. badger type-B”, as well as “B. annae” were reported [18]. In dogs as typical hosts, in a worldwide context, three small Babesia spp., i.e. B. gibsoni, “B. annae” (syn. “T. annae”, B. cf. microti) and B. conradae, as well as three large Babesia spp. (B. canis, B. vogeli and B. rossi) were hitherto known to occur [3] (Fig. 1). Rare accounts also attest the occasional finding of the DNA of piroplasms in dogs, for which the typical hosts are outside the order Carnivora (e.g. B. caballi [10]). However, this is the first molecular identification of the DNA from a badger-associated Babesia sp. in canine hosts. Taking into account the simultaneous occurrence of DNA from “Babesia sp. Meles-Hu1” in six dogs, one of which showed typical clinical signs of babesiosis, results of the present study suggest that the occurrence of “Babesia sp. Meles-Hu1” is not exceptional in dogs, and it might even have a pathogenic role in this host species.

The badger-associated Babesia genotype identified here corresponded to “Babesia sp. Meles-Hu1”, which was formerly identified in a badger in eastern Hungary (GenBank: KX218234), suggesting a widespread occurrence of this species in the country. Babesia canis genotypes “A” and “B” (GenBank: KP835549 and KP835550, respectively) were also reported formerly in Hungary from bats [21] and from questing D. reticulatus ticks [22].

The significantly higher number of “Babesia sp. Meles-Hu1”-positive samples among dogs frequently taken to forests (including hunting dogs) highlights the importance of the preferred habitat of badgers (i.e. forest in Hungary [23]) in the epidemiology of this infection. In particular, dogs in such environments, especially when getting into contact with badgers during hunting, may acquire infestation with I. canisuga from badgers or from the burrows of badgers.

On the other hand, all B. canis-positive dogs were identified in the sample group not associated with forests, most likely reflecting that the vector of this piroplasm (D. reticulatus) is an “open country tick species” [24] (in Hungary [25]). In addition, the time shift between PCR-positive samples containing either B. canis or “Babesia sp. Meles-Hu1” is also most likely a consequence of differences in the activity periods of their vectors.

Ixodes canisuga was proposed to be the vector of the badger-associated piroplasm, B. missirolli [17], and this vector potential was confirmed by the present results from the molecular analysis of badger ticks (I. canisuga vs I. hexagonus). Dogs were formerly reported to harbor I. canisuga in Hungary [26]. Such occasions would allow tick-borne badger-to-dog transmission. On the other hand, taking into account the usage of dogs during badger hunting in the evaluated region of Hungary, oral infection of relevant dogs with “Babesia sp. Meles-Hu1” cannot be completely ruled out. In support of this, (i) blood-borne transmission of babesiae was reported in fighting dogs (B. gibsoni [27]), and (ii) oral infection is possible in the case of the type-species of the phylogenetic group where “Babesia sp. Meles-Hu1” belongs (B. microti [28]).

Phylogenetic analysis showed that “Babesia sp. Meles-Hu1” identified in dogs belongs to the B. microti group, where piroplasms of the Mustelidae, Canidae and Procyonidae (suborder Caniformia) cluster together and are separated (with 100% support) from a phylogenetic group containing piroplasms of Feliformia (Fig. 1). Several examples attest that different species of carnivores within a family (e.g. Canidae) are susceptible to the same piroplasm (e.g. B. canis), while Babesia spp. are also known to infect carnivorous hosts from different families of Caniformia, as exemplified by high prevalences of B. microti-like infections in both Canidae and Procyonidae [12].

Conclusions

This is the first detection of the DNA from a badger-associated Babesia sp. in dogs, one of which also showed relevant clinical signs. In this study, the number of dogs with blood samples containing the DNA of “Babesia sp. Meles-Hu1” exceeded the number of B. canis-positive samples, therefore these findings should not be regarded as isolated cases. It is assumed that dogs, which are used for hunting or frequently visit forests, are more likely to be exposed to this piroplasm, probably as a consequence of infestation with I. canisuga from badgers or from the burrows of badgers. These results suggest that “Babesia sp. Meles-Hu1” should be added to the range of piroplasms, which are naturally capable of infecting hosts from different families of Caniformia.

References

Schreeg ME, Marr HS, Tarigo JL, Cohn LA, Bird DM, Scholl EH, et al. Mitochondrial genome sequences and structures aid in the resolution of Piroplasmida phylogeny. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0165702.

Kuttler KL. World-wide impact of babesiosis. In: Ristic M, editor. Babesiosis of domestic animals and man. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1988. p. 1–22.

Kjemtrup AM, Kocan AA, Whitworth L, Meinkoth J, Birkenheuer AJ, Cummings J, et al. There are at least three genetically distinct small piroplasms from dogs. Int J Parasitol. 2000;30:1501–5.

Jinnai M, Kawabuchi-Kurata T, Tsuji M, Nakajima R, Fujisawa K, Nagata S, et al. Molecular evidence for the presence of new Babesia species in feral raccoons (Procyon lotor) in Hokkaido, Japan. Vet Parasitol. 2009;162:241–7.

Jinnai M, Kawabuchi-Kurata T, Tsuji M, Nakajima R, Hirata H, Fujisawa K, et al. Molecular evidence of the multiple genotype infection of a wild Hokkaido brown bear (Ursus arctos yesoensis) by Babesia sp. UR1. Vet Parasitol. 2010;173:128–33.

Ikawa K, Aoki M, Ichikawa M, Itagaki T. The first detection of Babesia species DNA from Japanese black bears (Ursus thibetanus japonicus) in Japan. Parasitol Int. 2011;60:220–2.

Leclaire S, Menard S, Berry A. Molecular characterization of Babesia and Cytauxzoon species in wild South African meerkats. Parasitology. 2015;142:543–8.

Williams B, Berentsen A, Shock B, Teixiera M, Dunbar M, Becker M, et al. Prevalence and diversity of Babesia, Hepatozoon, Ehrlichiha and Bartonella in wild and domestic carnivores from Zambia, Africa. Parasitol Res. 2014;113:911–8.

Criado-Fornelio A, Martinez-Marcos A, Buling-Sarana A, Barba-Carretero JC. Molecular studies on Babesia, Theileria and Hepatozoon in southern Europe - Part I. Epizootiological aspects. Vet Parasitol. 2003;113:189–201.

Beck R, Vojta L, Mrljak V, Marinculić A, Beck A, Zivicnjak T, et al. Diversity of Babesia and Theileria species in symptomatic and asymptomatic dogs in Croatia. Int J Parasitol. 2009;39:843–8.

Beck A, Huber D, Polkinghorne A, Kurilj AG, Benko V, Mrljak V, et al. The prevalence and impact of Babesia canis and Theileria sp. in free-ranging grey wolf (Canis lupus) populations in Croatia. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:168.

Alvarado-Rybak M, Solano-Gallego L, Millán J. A review of piroplasmid infections in wild carnivores worldwide: importance for domestic animal health and wildlife conservation. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:538.

Hornok S, Horváth G. First report of adult Hyalomma marginatum rufipes (vector of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus) on cattle under a continental climate in Hungary. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:170.

Hornok S, de la Fuente J, Horváth G, Fernández de Mera IG, Wijnveld M, Tánczos B, et al. Molecular evidence of Ehrlichia canis and Rickettsia massiliae in ixodid ticks of carnivores from south Hungary. Acta Vet Hung. 2013;61:42–50.

Babos S. Kullancsok - Ixodidea. Fauna Hungariae. 1965;18:1–38. (In Hungarian).

Hornok S, Sándor AD, Beck R, Farkas R, Beati L, Kontschán J, et al. Contributions to the phylogeny of Ixodes (Pholeoixodes) canisuga, I. (Ph.) kaiseri, I. (Ph.) hexagonus and a simple pictorial key for the identification of their females. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:545.

Biocca E, Corradetti A. Babesia missirolli, n. sp., parassita del tasso (Meles meles). Riv Parassitol. 1952;13:17.

Barandika JF, Espí A, Oporto B, del Cerro A, Barral M, Povedano I, et al. Occurrence and genetic diversity of piroplasms and other Apicomplexa in wild carnivores. Parasitology Open. 2016;2:e6.

Casati S, Sager H, Gern L, Piffaretti JC. Presence of potentially pathogenic Babesia sp. for human in Ixodes ricinus in Switzerland. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2006;13:65–70.

Hornok S, Mester A, Takács N, Fernández de Mera IG, de la Fuente J, Farkas R. Re-emergence of bovine piroplasmosis in Hungary: has the etiological role of Babesia divergens been taken over by B. major and Theileria buffeli? Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:434.

Hornok S, Estók P, Kováts D, Flaisz B, Takács N, Szőke K, et al. Screening of bat faeces for arthropod-borne apicomplexan protozoa: Babesia canis and Besnoitia besnoiti-like sequences from Chiroptera. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:441.

Hornok S, Kartali K, Takács N, Hofmann-Lehmann R. Uneven seasonal distribution of Babesia canis and its two 18S rDNA genotypes in questing Dermacentor reticulatus ticks in urban habitats. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2016;7(5):694–7.

Márton M, Markolt F, Szabó L, Kozák L, Lanszki J, Patkó L, et al. Den site selection of the European badger, Meles meles and the red fox, Vulpes vulpes in Hungary. Fol Zool. 2016;65:72–9.

Uspensky I. Preliminary observations on specific adaptations of exophilic ixodid ticks to forests or open country habitats. Exp Appl Acarol. 2002;28:147–54.

Hornok S, Farkas R. Influence of biotope on the distribution and peak activity of questing ixodid ticks in Hungary. Med Vet Entomol. 2009;23:41–6.

Földvári G, Farkas R. Ixodid tick species attaching to dogs in Hungary. Vet Parasitol. 2005;129:125–31.

Jefferies R, Ryan UM, Jardine J, Broughton DK, Robertson ID, Irwin PJ. Blood, bull terriers and babesiosis: further evidence for direct transmission of Babesia gibsoni in dogs. Aust Vet J. 2007;85:459–63.

Malagon F, Tapia JL. Experimental transmission of Babesia microti infection by the oral route. Parasitol Res. 1994;80:645–8.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the contributions by the staff at the Veterinary Clinic in Csurgó.

Funding

Molecular work was supported by OTKA 115854. This research was also supported by the 12190-4/2017/FEKUTSTRAT grant of the Hungarian Ministry of Human Capacities.

Availability of data and materials

The sequences obtained and/or analyzed during the current study are deposited in GenBank under accession numbers (MG778912-MG778915). All other relevant data are included in the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SH designed the study, supervised molecular phylogenetic analyses and wrote the manuscript. GH provided samples. NT and JK performed molecular and phylogenetic analyses, respectively. KSZ extracted the DNA. RF significantly helped the organization of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Dogs were sampled during regular veterinary care and all badgers were road-killed animals, therefore no ethical permission was needed.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hornok, S., Horváth, G., Takács, N. et al. Molecular identification of badger-associated Babesia sp. DNA in dogs: updated phylogeny of piroplasms infecting Caniformia. Parasites Vectors 11, 235 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-018-2794-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-018-2794-8