Abstract

Background

Depression is one of the most disabling and chronic mental illnesses. Despite its high burden, many people suffering from depression did not perceive that they had a treatable illness and consequently most of them did not seek professional help. The aim of this study was to assess the level of professional help-seeking behavior and associated factors among individuals with depression.

Methods and materials

The community-based cross-sectional study was conducted among residents of Dessie, Northeast Ethiopia. First, 1165 residents were screened for depression using patient health questionnaire and then 226 individuals who were screened positive for probable depression were interviewed with General Help-Seeking Questionnaire to assess the professional help-seeking behavior of participants with depression. Major associated variables were identified using logistic regression with 95% confidence interval (CI), and variables with a p value less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Among the total participants with depressive symptoms, only 25.66% of them did seek professional help. Being female [adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 2.769, 95% CI (1.280, 5.99)], current alcohol drinking [AOR = 2.74, 95% CI (1.265, 5.940)], co-morbid medical-surgical illness [AOR = 4.49, 95% CI (1.823, 11.071)], perceiving depression as illness [AOR = 2.44, 95% CI (1.264, 4.928)], having moderate depressive symptoms [AOR = 2.54, 95% CI (1.086, 5.928)] and moderately severe depressive symptoms [AOR = 7.67, 95% CI (2.699, 21.814)] were significantly associated with help seeking behavior of participants.

Conclusions

Level of professional help-seeking behavior is as low as previous studies in different countries. The severity of depressive symptoms, co-morbidity of medical–surgical illness, current drinking of alcohol, being female, and perceiving depression as illness were significantly associated with professional help-seeking behavior for depressive symptoms. Working on mental health literacy in the community is important to increase help-seeking behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Depression affects more than 300 million people worldwide [1] and is the second leading cause of global burden of diseases, which is also projected to be the first by 2020 [2]. Depression constitutes 40% of diagnosis of mental illnesses [3]. The lifetime prevalence ranges from 11 to 15% and its 12 months prevalence is about 6% in the global setting [4]. Moreover, people with depressive disorders have 40% greater chance of premature death, and less quality of life than the general population [5, 6].

Though depression has such a high magnitude and burden, individuals with depression had a low level of professional help-seeking behavior [7, 8]. Mostly, individuals with depression are reluctant to seek help from mental health professionals; rather they seek informal help from friends, family, and traditional healers before getting professional help as the problem gets more complicated [9, 10].

The rate of seeking help from professionals for depression is below 25% in the global setting [1]. According to the WHO survey of mental health service use for anxiety, mood disorders, and substance use disorders, the magnitude of seeking professional help within 12 months of onset of mental illness was from 1.6% in Nigeria to 17.9% in the USA. Previous evidence indicated that help-seeking behavior was from 17 to 47% in different parts of the world [11,12,13,14,15]. From those who did seek professional help, a small proportion of them did get specialized mental health care as indicated by 5.7% in South Africa, 7.7% in Mexico, and 9.5% in Iran [14,15,16].

In Ethiopia, professional help-seeking behavior was reported by 22.9% of individuals with depression [17]. In Ethiopia, it is common to try many alternative traditional and religious helps before actual health care seeking for symptoms of mental illness including depression. Thirty-one percent of patients seeking care from priests/holy water/church and fear of stigma was the major reason to not to seek professional help [18,19,20]. Gender, marital status, education and severity of illness symptoms were also reported elsewhere in the globe as associated factors [11,12,13, 21].

Low help seeking is the main reason that increases the burden and complexity of depressive disorders and there is limited evidence on the professional help-seeking behavior of individuals with depression, especially in low-income settings [22]. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine the level of professional help-seeking behavior and associated factors among individuals with depressive symptoms in Dessie, Ethiopia.

Methods and materials

Study design and setting

This research is reported based on STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) statement [23]. A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted in Dessie Town, Northeast Ethiopia. Dessie town is 400 km far from the capital Addis Ababa. The town has 10 sub-cities with the total population of 205,000 (CSA, 2007). Psychiatric service is delivered through a referral public hospital and other private institutions.

Procedures

The total sample size for the study was calculated single population proportion formula by considering 34% proportion of depressive symptoms (found from the pilot test), with 4% margin of error, confidence level 95%, design effect of 2, and 10% non-response rate:

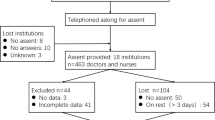

where n is the sample size, \(Z_{\alpha /2}\) for 95% confidence interval = 1.96, p is the proportion of depressive symptoms, and d is the margin of error. Hence, with those assumptions, the finale sample size was 1186. From the total sample size, 1165 participants (54.68% were females) completed the screening interview with PHQ-9 which makes the response rate 98.22%.

Multistage sampling technique was used to select the sub-cities and subsequent administrative villages. The households in the administrative villages were randomly selected, and one adult member of the house hold was randomly selected for the interview towards depressive symptoms. All individuals (226) who were screened positive for depressive symptoms (129 females) were interviewed for help-seeking behavior. The interview was done by trained data collectors (four Bachelor holder nurses) and was supervised by two Masters holder mental health professionals in June 2015.

The dependent variable for this study was professional help-seeking behavior for depressive symptoms and the independent variables were sociodemographic variables, psychosocial variables, and clinical variables.

Measurements

The questionnaire was composed of three parts to screen depressive symptoms (PHQ-9), to assess help-seeking behavior (GHSQ), and to identify important factors associated with help-seeking behavior. The questionnaire was first developed in English by the investigators and translated to the local language, Amharic by an independent translator. The Amharic version was back-translated to English by another translator to check the consistency with the original version. The pre-test was done to check the suitability and simplicity of the questionnaire, and some arrangements were done based on the results from the pre-test.

Depressive symptoms were screened by the Ethiopian version of Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) which has been validated in Ethiopia with 78.3% sensitivity and 64% specificity with cutoff point five [24]. Professional help-seeking behavior was assessed by the GHSQ which has very good validity to screen help-seeking behavior (α = 0.83). Participants were asked whether they did seek help or not for their depressive symptoms; and if they did seek help, they were interviewed for the source of help [25]. GHSQ has been adapted and used in Ethiopia to assess the actual help-seeking behavior [26]. The psychometric property is also very good in the current study (α = 0.80).

Social support was assessed using a three-item Oslo Social Support Scale (OSSS-3) which has a sum score ranged from 3 to 14 (poor social support = 3–8, intermediate social support = 9–11, and strong social support = 12–14) [27]. Although OSS-3 is not been validated, it has been widely used and has good utility in Ethiopian context [26, 28,29,30]. The reliability test for OSS-3 in the current study was good (α = 0.68). Perception about depression as an illness was assessed using the 9 items Likert scale of the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (BIPQ), which is with good reliability test in the current study (α = 0.70). The mean score of above 38.18 indicates that the participant perceived depression as illness. The test–retest reliability (Pearson’s correlations rang 0.5–0.7) and predictive validity are good [31,32,33,34]. Perceived public stigma and self-stigma against depression were assessed using the 18 items depression stigma scale (DSS). The sum score of DSS is ranged from 0 to 36 and the mean score was used to indicate the presence or absence of both personalized and public stigma with good psychometric property (α = 0.77) [35, 36]. The reliability test of DSS in the current study also showed good psychometric property (α = 0.75).

Analysis

Data were entered into Epi info version 7 and analyzed with SPSS version 21. Tables and other descriptive statistics were used to report descriptive data. Bivariate analysis was done between the outcome variable and each independent variable. Multivariable logistic regression was used to identify associated factors and the strength of association was shown by odds ratio and their respective 95% confidence intervals. Variables with p value less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant. The regression model was constructed with dependent variable (professional help seeking) and independent variables (sex, family history of mental illness, ever use of tobacco products, current alcohol drinking, having a diagnosed medical or surgical illness, perception about depression as illness, social support and severity of depression). Test of model fit was checked by Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit, which showed that the model adequately describes the data (p = 0.6), and the Cox and Snell R Square was also 0.53.

Ethical clearance was obtained from an ethical review board of the University of Gondar and an anonymous questionnaire was used to ensure confidentiality. Participation in the study was voluntary based by informing the participants about the aim of the study and their right to refuse the interview. All the responses given by them were kept confidential using a password. Written consent was taken from each participant before the interview. Participants with severe depressive symptoms were linked to the nearest health facility for appropriate care.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

From 226 participants screened positive for depressive symptoms, all of them had completed the questionnaire. More than half of the participants (57.1%) were single, 129 (57.1%) were females, and more than half of the participants were in age group of 18–25 with a median age of 23 (Table 1).

Clinical characteristics

Seven (3.1%) of the participants reported the previous history psychiatric illness, 11 (4.9%) had a family history of mental illness, and 39 (17.3%) of them had a reported known medical condition. HIV/AIDS, TB, Pelvic ulcer disease and renal conditions were among the mentioned co-morbid illnesses (Table 2).

Psychosocial factors

Depression was not considered as illness by 55.8% of the participants and the remaining 100 (44.2%) consider depression as a life-threatening illness. Perceived stigma towards depression was reported by a significant proportion of the participants, of which, 121 (53.5%) reported self-stigma and 123 (54.4%) reported perceived public stigma. Moderate social support was reported by 122 (54%) participants while the remaining participants reported poor social support (34.1%) and strong social support (11.9%).

Professional help-seeking behavior

The level of professional help-seeking behavior among individuals with depressive symptoms was 58 (25.66%). The remaining (74.44%) of individuals with depressive symptoms sought informal help from non-professional sources such as friends 95 (56.54%), families (13.69%), spiritual leaders (10.12%), spouse (7.73%). Twenty (11.9%) participants did not get any type of help for their depressive symptoms.

Factors associated with the level of professional help-seeking behavior

Variables with significant association for help-seeking behavior were being female [AOR = 2.77, 95% CI (1.28, 5.99)], current drinking of alcohol [AOR = 2.74, 95% CI (1.27, 5.94)], having a diagnosed medical or surgical illness [AOR = 4.49, 95% CI (1.82, 11.07)], perceiving depression as severe illness [AOR = 2.44 95% CI (1.26, 4.93)], having moderate depressive symptoms [AOR = 2.54, 95% CI (1.09, 5.93)] and moderately severe depressive symptoms [AOR = 7.67, 95% CI (2.69, 21.81)](Table 2).

Discussion

In the current study, the level of professional help seeking was 25.66% (95% CI 20, 31.35) which is consistent with previous studies in Ethiopia (22.9%), Mexico (20.15%), and Australia (27.6%) [14, 17, 37]. However, the current finding was lower as compared with the study done in South Africa (43%), England (36%), Sweden (47.1%), and Finland (39.6%) [12, 38,39,40]. Professional help-seeking behavior is affected by common cultural beliefs in traditional medicine and this is common in lower and middle-income counties including Ethiopia [41]. On the other hand, scarce mental health resource is also another barrier to seek help from mental health professionals [8, 42]. Individuals with depressive symptoms also prefer supports from family members and close friends [7].

Considering depression as a treatable illness is one of the deriving factors to seek professional help; however, more than half (55.8%) of the participants did not consider depressive symptoms as illness, which may hinder health-seeking behavior. Stigma towards depressive symptoms might also contribute to lower help-seeking behavior to their illness as indicated by more than half of the participants reported perceived self and public stigma. The level of professional help-seeking behavior for depressive symptoms in this study was higher than that of Nigeria (16.9%) [43].

The severity of depressive symptoms was significantly associated with the level of professional help-seeking behavior. The odds of seeking help from professionals for participants with moderate and moderately severe depressive symptoms were 2.54 and 7.67 times more as compared with participants with mild symptoms, respectively. Functional impairment and physical complaints in addition to the loss of roles in the community in case of severe depressive symptoms are an important driving factor to seek help. This finding was supported by studies done in Finland and South Africa [44, 45].

Co-morbidity of surgical and medical illness was significant to seek help from professionals for depressive symptoms. Individuals tend to visit health facilities for a physical illness which indirectly leads them to the diagnosis of depression. This condition might lead the individuals with depressive symptoms to seek professional help [12, 38, 39]. It is relatively not stigmatizing to seek help for most of the medical illnesses; hence, individuals with depressive symptoms who had co-morbid medical illnesses may seek professional help for acute medical complaints such as headaches or abdominal pain [46]. Perceiving depression as more severe and malignant illness was also had more than two-times odds for professional help-seeking behavior which is consistent with the Mexican study [14].

Females were 2.8 times more likely to seek professional help for their depressive symptoms as compared with males. Traditional decision-making power and greater control of social status in men than women make it difficult to accept the diagnosis of depression, which also leads them to lower help-seeking behavior for their depressive symptoms [47]. This finding was supported by a study in Finland [40].

Current alcohol drinking problem was also significantly associated with professional help-seeking behavior for depressive symptoms. Drinking may aggravate the symptoms of depression and functional impairment makes the person seek any help from health professionals [48]. Unlike other studies [11, 12, 21], marital status and educational status were not statistically significant in the current study.

Conclusion

Level of professional help-seeking behavior is as low as previous studies in different countries. The severity of depressive symptoms, co-morbidity of medical-surgical illness, current drinking of alcohol, being female and perceiving depression as illness was significantly associated with professional help-seeking behavior for symptoms of depression. So, screening depressive symptoms in medical settings and community awareness creation about depression to increase mental health literacy and perception is essential.

Limitation of the study

The first limitation is that this study did not investigate the specific medical-surgical co-morbid conditions. The second limitation is we did not assess whether the individuals who seek professional help did get standard treatment or not. The third limitation is that those with older age (40 and above) seem underrepresented and future research may consider it. The final possible limitation can be the validity of instruments except for PHQ-9. But, we assure the understandability of the tools before the study with a pre-test.

References

World Federation for Mental Health. Depression: a global crisis. World mental health day, October 10 2012. Occoquan: World Federation for Mental Health; 2012.

Becker AE, Kleinman A. Mental health and the global agenda. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(1):66–73.

Patel V, Saxena S. Transforming lives, enhancing communities—innovations in global mental health. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(6):498–501.

Bromet E, Andrade LH, Hwang I, Sampson NA, Alonso J, De Girolamo G, De Graaf R, Demyttenaere K, Hu C, Iwata N, et al. Cross-national epidemiology of DSM-IV major depressive episode. BMC Med. 2011;9(1):90.

World Health Organization. Mental health action plan 2013–2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

Carta MG, D’Oca S, Atzeni M, Perra A, Moro MF, Sancassiani F, Mausel G, Nardi AE, Minerba L, Brasesco V. Quality of life of Sardinian immigrants in Buenos Aires and of People living in Italy and Sardinia: does the kind of care have a role for people with depression? Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2016;12:158–66.

Carta MG, Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H, Holzinger A, Floris F, Moro MF. Perception of depressive symptoms by the Sardinian public: results of a population study. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:57.

Moro MF, Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H, Holzinger A, Piras AP, Cutrano F, Mura G, Carta MG. Whom to ask for professional help in case of major depression? help-seeking recommendations of the Sardinian public. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42(6):704–13.

Oliver MI, Pearson N, Coe N, Gunnell D. Help-seeking behaviour in men and women with common mental health problems: cross-sectional study. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186(4):297–301.

Nsereko JR, Kizza D, Kigozi F, Ssebunnya J, Ndyanabangi S, Flisher AJ, Cooper S, et al. Stakeholder’s perceptions of help-seeking behaviour among people with mental health problems in Uganda. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2011;5:5.

Conner KO, Copeland VC, Grote NK, Koeske G, Rosen D, Reynolds CF, Brown C. Mental health treatment seeking among older adults with depression: the impact of stigma and race. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(6):531–43.

Wallerblad A, Möller J, Forsell Y. Care-seeking pattern among persons with depression and anxiety: a population-based study in Sweden. Int J Fam Med. 2012;2012:1–9.

Perkins D, Fuller J, Kelly BJ, Lewin TJ, Fitzgerald M, Coleman C, Inder KJ, Allan J, Arya D, Roberts R, et al. Factors associated with reported service use for mental health problems by residents of rural and remote communities: cross-sectional findings from a baseline survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):157.

Pérez-Zepeda MU, Arango-Lopera VE, Wagner FA, Gallo JJ, Sánchez-García S, Juárez-Cedillo T, García-Peña C. Factors associated with help-seeking behaviors in Mexican older individuals with depressive symptoms: a cross-sectional study: help seeking in older individuals with depressive symptoms. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(12):1260–9.

Modabernia MJ, Tehrani HS, Fallahi M, Shirazi M, Modabbernia AH. Prevalence of depressive disorders in Rasht, Iran: a community based study. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2008;4(1):20.

Seedat S, Williams DR, Herman AA, Moomal H, Williams SL, Jackson PB, Myer L, Stein DJ. Mental health service use among South Africans for mood, anxiety and substance use disorders. South Afr Med J. 2009;99(5).

Hailemariam S, Tessema F, Asefa M, Tadesse H, Tenkolu G. The prevalence of depression and associated factors in Ethiopia: findings from the National Health Survey. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2012;6(1):23.

Bekele YY, Flisher AJ, Alem A, Baheretebeb Y. Pathways to psychiatric care in Ethiopia. Psychol Med. 2009;39(3):475–83.

Girma E, Tesfaye M. Patterns of treatment seeking behavior for mental illnesses in Southwest Ethiopia: a hospital based study. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:138.

Mayston R, Alem A, Habtamu A, Shibre T, Fekadu A, Hanlon C. Participatory planning of a primary care service for people with severe mental disorders in rural Ethiopia. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31(3):367–76.

Wang PS, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Bruffaerts R, de Girolamo G, de Graaf R, Gureje O, et al. Use of mental health services for anxiety, mood, and substance disorders in 17 countries in the WHO world mental health surveys. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):841–50.

Andrews G, Sanderson K, Slade T, Issakidis C. Why does the burden of disease persist? Relating the burden of anxiety and depression to effectiveness of treatment. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(4):446–54.

Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, Initiative S. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 2007;4(10):e296.

Gelaye B, Williams MA, Lemma S, Deyessa N, Bahretibeb Y, Shibre T, Wondimagegn D, Lemenhe A, Fann JR, Vander Stoep A, et al. Validity of the patient health questionnaire-9 for depression screening and diagnosis in East Africa. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210(2):653–61.

Wilson CJ, Deane FP, Ciarrochi J, Rickwood D. Measuring help-seeking intentions. Properties of the general help seeking questionnaire. Can J Counsel Psychother (Revue canadienne de counseling et de psychothérapie). 2007;39(1).

Azale T, Fekadu A, Hanlon C. Treatment gap and help-seeking for postpartum depression in a rural African setting. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:196.

Abiola T, Udofia O, Zakari M, et al. Psychometric properties of the 3-item Oslo Social Support scale among clinical students of Bayero University Kano, Nigeria. Malays J Psychiatry. 2013;22(2):32–41.

Bisetegn TA, Mihretie G, Muche T. Prevalence and predictors of depression among pregnant women in Debretabor town, Northwest Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(9):e0161108.

Duko B, Gebeyehu A, Ayano G. Prevalence and correlates of depression and anxiety among patients with tuberculosis at WolaitaSodo University Hospital and Sodo Health Center, WolaitaSodo, South Ethiopia, cross sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:214.

Fekadu A, Rane LJ, Wooderson SC, Markopoulou K, Poon L, Cleare AJ. Prediction of longer-term outcome of treatment-resistant depression in tertiary care. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;201(5):369–75.

Broadbent E, Petrie KJ, Main J, Weinman J. The brief illness perception questionnaire. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60(6):631–7.

Knowles SR, Wilson JL, Connell WR, Kamm MA. Preliminary examination of the relations between disease activity, illness perceptions, coping strategies, and psychological morbidity in Crohn’s disease guided by the common sense model of illness. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(12):2551–7.

Basu S, Poole J. The brief illness perception questionnaire. Occup Med. 2016;66(5):419–20.

Boerema AM, Zoonen KV, Cuijpers P, Holtmaat CJM, Mokkink LB, Griffiths KM, Kleiboer AM. Psychometric Properties of the Dutch Depression Stigma Scale (DSS) and associations with personal and perceived stigma in a depressed and community sample. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(8):e0160740.

Griffiths KM, Christensen H, Jorm AF. Predictors of depression stigma. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8(1):25.

Griffiths KM, Christensen H, Jorm AF, Evans K, Groves C. Effect of web-based depression literacy and cognitive–behavioural therapy interventions on stigmatising attitudes to depression randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185(4):342–9.

Judd F, Jackson H, Komiti A, Murray G, Fraser C, Grieve A, Gomez R. Help-seeking by rural residents for mental health problems: the importance of agrarian values. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40(9):769–76.

Brown J, Evans-Lacko S, Aschan L, Henderson MJ, Hatch SL, Hotopf M. Seeking informal and formal help for mental health problems in the community: a secondary analysis from a psychiatric morbidity survey in South London. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(1):275.

Andersson LMC, Schierenbeck I, Strumpher J, Krantz G, Topper K, Backman G, Ricks E, Van Rooyen D. Help-seeking behaviour, barriers to care and experiences of care among persons with depression in Eastern Cape, South Africa. J Affect Disord. 2013;151(2):439–48.

Aromaa E, Tolvanen A, Tuulari J, Wahlbeck K. Personal stigma and use of mental health services among people with depression in a general population in Finland. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11(1):52.

Mascayano F, Armijo JE, Yang LH. Addressing stigma relating to mental illness in low- and middle-income countries. Front Psychiatry. 2015;6:38.

Patel V. Mental health in low- and middle-income countries. Br Med Bull. 2007;81–82(1):81–96.

Gureje O, Uwakwe R, Oladeji B, Makanjuola VO, Esan O. Depression in adult Nigerians: results from the Nigerian Survey of Mental Health and well-being. J Affect Disord. 2010;120(1):158–64.

Hämäläinen J, Isometsä E, Sihvo S, Pirkola S, Kiviruusu O. Use of health services for major depressive and anxiety disorders in Finland. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25(1):27–37.

Williams DR, Herman A, Stein DJ, Heeringa SG, Jackson PB, Moomal H, Kessler RC. Twelve-month mental disorders in South Africa: prevalence, service use and demographic correlates in the population-based South African Stress and Health Study. Psychol Med. 2008;38(02):211–20.

Katon WJ. Epidemiology and treatment of depression in patients with chronic medical illness. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13(1):7–23.

Judd F, Komiti A, Jackson H. How does being female assist help-seeking for mental health problems? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2008;42(1):24–9.

Chen L-Y, Crum RM, Martins SS, Kaufmann CN, Strain EC, Mojtabai R. Service use and barriers to mental health care among adults with major depression and comorbid substance dependence. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(9):863–70.

Authors’ contributions

All authors equally contributed from the conception till the completion of this project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We are very thankful to the study participants for their volunteer and genuine participation and Amanuel Mental Specialized Hospital for the financial support. Wubalem Fekadu is supported through the DELTAS Africa Initiative [DEL-15-01]. The DELTAS Africa Initiative is an independent funding scheme of the African Academy of Sciences (AAS)’s Alliance for Accelerating Excellence in Science in Africa (AESA) and supported by the New Partnership for Africa’s Development Planning and Coordinating Agency (NEPAD Agency) with funding from the Wellcome Trust [DEL-15-01] and the UK government.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The materials and data related to this research will be available upon reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from an ethical review board of the University of Gondar and an anonymous questionnaire was used to ensure confidentiality. Participation in the study was voluntary based by informing the participants about the aim of the study and their right to refuse the interview. All the responses given by them was kept confidential using a password. Written consent was taken from each participant before the interview. Participants with severe depressive symptoms were linked to the nearest health facility for appropriate care.

Funding

This research was supported by Amanuel Mental Specialized Hospital.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Menberu, M., Mekonen, T., Azale, T. et al. Health care seeking behavior for depression in Northeast Ethiopia: depression is not considered as illness by more than half of the participants. Ann Gen Psychiatry 17, 34 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-018-0205-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-018-0205-3