Abstract

Background

Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) experience symptoms that vary over the day. Symptoms at the start of the day might influence physical activity during the rest of the day. Therefore, physical activity during the course of the day was studied in patients with low and high morning symptom scores.

Methods

This cross-sectional observational study included patients with moderate to very severe COPD. Morning symptoms were evaluated with the PRO-morning COPD Symptoms Questionnaire (range 0–60); the median score was used to create two groups (low and high morning symptom scores). Physical activity was examined with an accelerometer. Activity parameters during the night, morning, afternoon and evening were compared between patients with low and high morning symptom scores using independent t-tests or Mann-Whitney U tests.

Results

Seventy nine patients were included. Patients were aged (mean ± SD) 65.6 ± 8.8 years with a mean forced expiratory volume in 1 s of 55 ± 17%predicted. Patients with low morning symptom scores (score < 17.0) took more steps in the afternoon (p = 0.015) and morning (p = 0.030). There were no significant differences during the evening and night.

Conclusion

Patients with high morning symptom scores took significantly fewer steps in the morning and afternoon than those with low morning symptom scores. Prospective studies are needed to prove causality between morning symptoms and physical activity during different parts of the day.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a worldwide problem with a high prevalence of years lived with disability [1]. COPD is associated with dyspnoea, fatigue and decreased physical activity. Regular physical activity in patients with COPD is associated with a lower risk of admissions and mortality [2]. Most previous studies reported on physical activity during day time solely [3,4,5,6]. When physical activity was measured over the course of the day, nuanced reporting on physical activity during different parts of the day was generally lacking [7,8,9,10]. Therefore, only little is known about physical activity in COPD patients during the night and early morning. Studying physical activity during the course of the day is important, because a symptomatic start to the day might influence physical activity during the rest of the day.

Patients with COPD experience the morning as most symptomatic part of the day [11, 12] and the night as second most symptomatic part of the day [12]. Studies have shown that morning symptoms are negatively associated with self-reported physical activity [13]. A negative association between morning symptoms and overall physical activity has been reported [14]. However, the relation between morning symptoms and objectively measured physical activity during different parts of the day has not been studied yet. From previous research it is known that morning symptoms influence self-care, housework and work activities [15]. We hypothesized that patients with high morning symptom scores are less active in the morning and during the rest of the day compared to patients with low morning symptom scores. Furthermore, detailed assessments of physical activity over the day could give insight which part might be most suitable for physical activity interventions. Therefore, the primary aim of this study was to examine physical activity during the course of the day depending on morning symptoms. In addition, self-reported physical activity was assessed to better understand which types of activities were generally undertaken.

Methods

Research design

The Morning symptoms in-Depth observAtional Study (MODAS) was a single centre, observational, cross-sectional study (study NL51951.058.15; www.toetsingonline.nl). The study was conducted from September 2015 to February 2017. The medical ethics committee from the Leiden University Medical Center (LUMC) approved the study protocol.

Participants

Detailed inclusion/exclusion criteria have been reported previously [14]. In summary, included in the study were patients aged 40 to 80 years. A physician had diagnosed them with COPD. They had moderate to very severe airflow limitation according to the Global initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) definitions [16]. Patients were exacerbation-free for at least 2 months. They were current or active smokers with at least 10 pack-years. Main exclusion criteria were the diagnosis of asthma; significant other lung disease, comorbidities and severe pain syndromes that impair exercise capacity. Patients were recruited from the LUMC and Alrijne hospital in Leiden (The Netherlands). Patients who were considered to be eligible were notified about the study by telephone or during an outpatient visit. Furthermore, patients were recruited by flyers in local papers. Eligible interested patients received an information letter. If the patient agreed to participate in the study, a study visit was scheduled. During the visit, written informed consent was obtained.

Assessments

During the baseline visit, demographic data and comorbidities were obtained by a physician. Patients were asked about their medication use and this was verified with a medication overview of the pharmacy. COPD-specific health-related quality-of-life, morning symptoms severity, self-reported physical activity and pre- and post-bronchodilator pulmonary function were assessed at the study center. After this visit, patients wore a triaxial accelerometer for seven consecutive days to objectively assess physical activity. When the physical activity measurements were finished, there was a follow-up telephone interview to report possible adverse events.

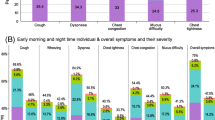

Morning symptom severity was evaluated with the PRO-Morning COPD Symptoms Questionnaire (pre-morning doses assessment) [17]. This questionnaire consists of six questions about dyspnoea, cough, sputum production, wheezing, chest tightness and limitations in the morning. Patients rated the severity of these symptoms with a Likert scale from 0 to 10 points. 0 for no symptoms; 10 points for symptoms as bad as they can imagine. The total score ranged from 0 to 60.

Physical activity was objectively measured with an accelerometer (Dynaport MoveMonitor, McRoberts BV, The Hague, the Netherlands) [18, 19]. This accelerometer was worn on the waist during the entire day for seven consecutive days resulting in real-life activity recording. To give insight into physical activity over the course of the day, days were divided in four parts of the day of each 6 hours: night (00.00 to 06.00), morning (06.00 to 12.00), afternoon (12.00 to 18.00) and evening (18.00 to 00.00). Duration of activity (standing, shuffling and walking) and inactivity (sitting and lying) in minutes was registered. The number of steps was recorded per part of the day and per hour. Patients were not allowed to wear the accelerometer during bathing or showering. The duration that the accelerometer was not worn was automatically registered. A measurement was considered valid when patients wore the accelerometer at least 90% per part of the day. Averages of the outcomes of valid parts of the day were calculated for each patient. Patients with only invalid parts of the day were excluded from analysis.

Patients filled out the Dutch version of the international physically activity questionnaire (IPAQ) [20]. In this questionnaire patients reported the number of minutes per day and days per week they were physical active in a 7-day period. Physical activity was categorized in four domains: work, transport, housework or leisure time related. Patients who reported more than 960 min a day each day of the week were excluded from this analysis in line with the activity calculation instructions of the IPAQ.

The Charlson Co-morbidity index was used to evaluate comorbidities (CCI) [21] and the three most common comorbidities were reported as percentage. COPD-specific health-related quality-of-life was assessed with the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ), [22] health status with the Clinical COPD Questionnaire (CCQ) [23] and dyspnoea in daily living with the medical modified research council (mMRC) [24]. All patients performed pre- and post-bronchodilator spirometry following ERS/ATS (European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society) standards in the morning between 08.30 and 11.00 (Care Fusion, Masterscreen PFT). [25,26,27] In this study, reported spirometry outcomes were post-bronchodilator values. Forced volume in 1 second (FEV1) was expressed in % predicted values (based on the Global Lung Function Initiative 2012) [26].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive data were reported as percentages, mean values ± standard deviations (SD) for normal distributed continuous variables and median with interquartile ranges (IQR) for non-normal distributed continuous variables. The study cohort was divided in two equal groups using the median score on the PRO-morning COPD Symptoms Questionnaire as cut-off. Differences in baseline characteristics between the two groups were compared with an independent t-test for continuous normal distributed variables; a Mann-Whitney U test for continuous non-normal distributed variables and chi-square test for categorical variables.

Differences in steps during the total day were compared between patients with low and high morning symptom scores using an independent t-test. Difference in steps and duration of (in)activity during different parts of the day were compared using an independent t-test or Mann-Whitney U test. To give an overview of the number of steps over the course of the day, steps per hour were plotted against hour of the day. Self-reported physical activity was compared using a Mann-Whitney U test. An explorative subgroup analysis was performed to examine long-acting pulmonary medication use. Long-acting pulmonary medication use was categorized in three groups: double bronchodilation (combination of a long-acting beta2 agonist (LABA) and long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA)), a single bronchodilator (LABA or LAMA use) or no use of long-acting pulmonary medication. The difference in mean number of steps in the morning was evaluated with a one way ANOVA.

Steps per hour were plotted against hour of the day for patients with low and high dyspnoea scores in daily living [16] to evaluate the impact of using a general symptom questionnaire instead of a specific morning symptom questionnaire to divide the study group.

A sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate the impact of adverse events during the study period; all patients who reported an adverse events, defined as self-reported illness or any somatic symptom for which the patient had to visit a health care provider, were excluded from the analyses.

For all analyses, a p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Missing data was not replaced. We used SPSS version 23 to perform the analyses.

Results

Patients

From 168 eligible patients who received the patient information form, 80 patients were included in the study and 79 patients had sufficient outcomes from accelerometry for analyses (Fig. 1). Table 1 shows demographics and baseline characteristics. Patients were (mean ± SD) 65.6 ± 8.8 years old and 53% were male. They had a mean FEV1 of 55 ± 17% predicted. Most patients were classified as COPD GOLD D (40.5%) and B (27.8%). Mean morning symptom score was 17.9 ± 11.8 with a range between 0 and 47. The median morning symptom score was 17.0 and was used as cut-off to separate the study cohort in two equal groups (Table 1).

Physical activity

Seventy nine patients wore the accelerometer 7 consecutive days. Thus, data from 553 days were collected from these 79 patients. 95.8% of the night, 91.0% of the morning, 96.7% of the afternoon and 93.9% the evening measurements fulfilled the quality standards and were included in the analysis. In each part of the day, most of the time was spent in inactivity (Table 2).

Mean number of steps per day was (mean ± SD) 5686 ± 3514. Patients with low morning symptom scores took 6598 ± 4243 steps a day; those with high morning symptom scores 4727 ± 2209 steps a day (mean difference 1871, p = 0.017). Patients with high morning symptom scores took significantly fewer steps during the morning (mean difference 669, p = 0.030) and during the afternoon (mean difference 1013, p = 0.015) than patients with low morning symptom scores (Table 3). Patients with low morning symptom scores were active for longer during the afternoon (mean difference 19, p = 0.040) and spent more minutes walking during the morning (mean difference 8, p = 0.020) and afternoon (mean difference 11, p = 0.010). There were peaks in mean number of steps at 15:00 (550 steps per hour) and at 12:00 (535 steps per hour) (Fig. 2). When patients with low and high morning symptom scores were categorized on medication use, there was no significant difference in mean number of steps in the morning between the groups (p = 0.057) (Additional file 1: Figure S1). When patients were categorized on high and low mMRC score, there was a significant difference in number of steps in the morning, afternoon and evening (Additional file 2: Figure S2).

Self-reported daily activities

Patients’ median [IQR] self-reported physical activity was 715 [319;1448] minutes a week. Patients spent most of their self-reported physical activity during leisure time (Table 4). Patients with low morning symptom scores spent significantly more time in transport and leisure time activities than those with high morning symptom scores. No significant differences were found for work, housework activities and total activity.

Sensitivity analysis

Seven patients reported an adverse event. One patient was exhausted due to the study visit, two patients reported pain in their hands, one had pneumonia, one had flu, one had sinusitis and one patient reported a visit to her general practitioner who prescribed a course of antibiotics and prednisone for pulmonary complaints. There were no serious adverse events.

Patients with adverse events have a significant lower quality of life and reported higher morning symptom scores (Additional file 3: Table S1). When excluding the patients with an adverse event from analyses, the cut-off n the PRO-morning COPD Symptoms Questionnaire to divide the cohort in two equal groups decreased to 15.0, since all patients with an adverse event were categorized in the high morning symptom score group. Results were nearly similar (Additional file 3: Table S2 and S3 and Additional file 4: Figure S3) apart from that there was no difference anymore in number of steps in the morning between patients with low and high morning symptom scores.

Discussion

This study was designed to evaluate physical activity during the course of the day in patients with moderate to severe COPD with low and high morning symptom scores. This is one of the first studies that explored physical activity in more detail during the course of the day using objective methodology. We showed that patients with high morning symptom scores took significantly fewer steps in the morning and afternoon than those with low morning symptom scores. There were no differences in physical activity in the evening and night between these two groups. Patients with high morning symptom scores spent less time in transport and leisure time than patients with low morning symptom scores.

The present study showed that patients with high morning symptom scores took fewer steps during the total day. This is in line with previous studies that have shown that daily symptoms were associated with lower physical activity levels [10]. One study in a primary care setting in men who are aged between 71 and 92 years, of whom 50% had chronic conditions, [28] reported that men were most active in the morning, followed by a substantial decline in steps per hour, with peaks at times 10:00, 14:00 and 22:00. Our study showed that the afternoon is the most active part of the day for patients with COPD with peaks in steps per hour at times 12:00 and 15:00. Thus, patients with COPD have different activity patterns during the course of the day. These findings are in line with another study of activity in COPD patients; this study showed the highest activity levels during the late morning and early afternoon, followed by a decline in activity [5]. The difference in activity patterns between older men and COPD patients could possibly be explained by known activity characteristics that are typical for COPD patients: lower walking speed, [29] walking with increased duration in time between steps, [30] doing activities slower, [12] taking more breaks, [12] performing daily activities in fewer bouts [4] and shorter bouts [4].

When analysing the activity patterns in a more detailed way, the present study showed that patients with high morning symptom scores were less active during the morning and afternoon than patients with low morning symptom scores. Systematic reviews have shown that multiple determinants have impact on physical activity [31] and that morning symptoms are associated with physical activity [13]. The etiology of morning symptoms is unknown. It can be speculated that inactivity in the afternoon in patients with high morning symptom scores could be due to the long-lasting effects of morning symptoms. It could also be true that patients with morning symptoms have more symptoms during the rest of the day [32]. Interestingly, we found no difference in active time during the evening and night between patients with low and high morning symptom scores. We did not expect this, because we expected that morning symptoms would be associated with less physical activity during each part of the day as patients reported in previous studies in which physical activity was not objectively measured [15, 33]. Exploring the assumption that morning symptoms influence physical activity in the morning, but not in the evening, the evening might be a suitable part of the day in which physical activity could be enhanced, especially in those with high morning symptom scores.

In line with previous research, the present study showed that patients spent most of their self-reported physical activity in leisure time [4]. Patients with high morning symptom scores spent less time in transport and leisure time activities than patients with low morning symptom scores. Encouraging physical activity in leisure time might result in more physical activity and can also increase quality of life [34]. A few previous studies have shown that inhaled medication decreased physical activity limitations due to morning symptoms [15, 35, 36]. An explorative analysis in the present study showed no differences in physical activity between no, single or double long-acting bronchodilator use. However, this study was not powered to show differences in medication use and future research regarding this topic is warranted.

A strength of the current study was 24-h a day accelerometry. This resulted in real-life activity recording without missing physical activity during the evening and the night. However, we did not have information regarding the time patients go to bed and woke up. Consequently, patients who got out of bed early in the morning (and were already awake for a couple of hours), were compared with patients who had only just awoken. Previous studies that assessed the association between morning symptoms and physical activity used self-reported questionnaires, while accelerometers are superior in physical activity assessment than questionnaires [13, 37]. Another strength was the inclusion of patients from an academic medical center, a local hospital and patients recruited by flyers in local papers. This resulted in a heterogeneous population that is generalizable to all patients with moderate to very severe COPD. A limitation of the study was that the accelerometer was not waterproof and patients were not allowed to wear it while taking a shower. For some patients, taking a shower is one of the main physical activities during a day, and this activity was not measured. This means, active time was underestimated. A second limitation is that morning symptoms were evaluated with a non-validated questionnaire. However, there is no validated morning symptom questionnaire available yet. Patients filled in the questionnaire at the study center and not at home at the time they woke up. This might have result in recall bias that might cause higher (or lower) total morning symptom scores. The mean morning symptom score was slightly higher than in a previous study that used the PRO-Morning COPD Symptoms Questionnaire too [17]. Therefore, it could be possible that the cut-off point to separate high from low morning symptom scores was too high. However, when patients with an AE were removed and the cut-off point dropped to 15.0, the outcomes were nearly the same. Another limitation is the observational design of the study. Therefore, it is not possible to prove whether morning symptoms are fully responsible for the differences in physical activity or that physical inactivity itself resulted in more symptoms due to muscle depletion and loss of physical condition.

The ERS reported in the physical activity statement in COPD that there are only a few randomised controlled trials that studied effects of treatment on physical activity and that there is a need for additional well-designed trials [29]. Taking the outcomes of this study into account, we suggest for future research to focus on two targets to improve physical activity: first, study the etiology of morning symptoms It would be valuable to measure night time symptoms, the effect of flow-limitation during the night (and the early morning) and the effects of spreading physical activity in relation to morning symptoms. Improvement in morning symptoms consequently might increase the number of steps in the morning and afternoon. Second, develop activity programs that encourage physical activity in the evening in addition to daily physical activities. Physical activity programs can be supported by telecoaching and step counters that provide direct feedback [3].

Conclusion

This study showed that patients with moderate to very severe COPD were most active in the afternoon. Patients with high morning symptom scores took significantly fewer steps in the morning and afternoon than those with low morning symptom scores. Prospective studies are needed to prove causality between morning symptoms and physical activity during different parts of the day.

Abbreviations

- ATS:

-

American thoracic society

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CCI:

-

Charlson Co-morbidity index

- CCQ:

-

Clinical COPD questionnaire

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- ERS:

-

European respiratory society

- FEV1 :

-

Forced expiratory volume in 1 s

- FVC:

-

Forced vital capacity

- GOLD:

-

Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease

- IPAQ:

-

international physical activity questionnaire

- IQR:

-

Interquartile ranges

- LABA:

-

Long-acting beta2 agonist

- LAMA:

-

Long-acting muscarinic antagonist

- LUMC:

-

Leiden University Medical Center

- mMRC:

-

Modified medical research council

- MODAS:

-

Morning symptoms in-Depth observational study

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SGRQ:

-

St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire

References

Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M, Shibuya K, Salomon JA, Abdalla S, Aboyans V, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2163–96.

Garcia-Aymerich J, Lange P, Benet M, Schnohr P, Anto JM. Regular physical activity reduces hospital admission and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population based cohort study. Thorax. 2006;61:772–8.

Demeyer H, Louvaris Z, Frei A, Rabinovich RA, de Jong C, Gimeno-Santos E, Loeckx M, Buttery SC, Rubio N, Van der Molen T, et al. Physical activity is increased by a 12-week semiautomated telecoaching programme in patients with COPD: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2017;72:415–23.

Donaire-Gonzalez D, Gimeno-Santos E, Balcells E, Rodriguez DA, Farrero E, de Batlle J, Benet M, Ferrer A, Barbera JA, Gea J, et al. Physical activity in COPD patients: patterns and bouts. Eur Respir J. 2013;42:993–1002.

Hecht A, Ma S, Porszasz J, Casaburi R. Methodology for using long-term accelerometry monitoring to describe daily activity patterns in COPD. Copd. 2009;6:121–9.

Pitta F, Troosters T, Probst VS, Langer D, Decramer M, Gosselink R. Are patients with COPD more active after pulmonary rehabilitation? Chest. 2008;134:273–80.

Van Remoortel H, Hornikx M, Demeyer H, Langer D, Burtin C, Decramer M, Gosselink R, Janssens W, Troosters T. Daily physical activity in subjects with newly diagnosed COPD. Thorax. 2013;68:962–3.

Waschki B, Kirsten AM, Holz O, Mueller KC, Schaper M, Sack AL, Meyer T, Rabe KF, Magnussen H, Watz H. Disease progression and changes in physical activity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:295–306.

Watz H, Waschki B, Boehme C, Claussen M, Meyer T, Magnussen H. Extrapulmonary effects of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on physical activity: a cross-sectional study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:743–51.

Watz H, Waschki B, Meyer T, Magnussen H. Physical activity in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:262–72.

Roche N, Chavannes NH, Miravitlles M. COPD symptoms in the morning: impact, evaluation and management. Respir Res. 2013;14:112.

Partridge MR, Karlsson N, Small IR. Patient insight into the impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the morning: an internet survey. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25:2043–8.

van Buul AR, Kasteleyn MJ, Chavannes NH, Taube C. Association between morning symptoms and physical activity in COPD: a systematic review. Eur Respir Rev. 2017;26:160033.

van Buul AR, Kasteleyn MJ, Chavannes NH, Taube C. The association between objectively measured physical activity and morning symptoms in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:2831–40.

O'Hagan P, Chavannes NH. The impact of morning symptoms on daily activities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30:301–14.

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Available form: http://www.goldcopd.org /. Accessed 25 Jan 2018.

Marin JM, Beeh KM, Clemens A, Castellani W, Schaper L, Saralaya D, Gunstone A, Casamor R, Kostikas K, Aalamian-Mattheis M. Early bronchodilator action of glycopyrronium versus tiotropium in moderate-to-severe COPD patients: a cross-over blinded randomized study (symptoms and pulmonary function in the moRnING). Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:1425–34.

Rabinovich RA, Louvaris Z, Raste Y, Langer D, Van Remoortel H, Giavedoni S, Burtin C, Regueiro EM, Vogiatzis I, Hopkinson NS, et al. Validity of physical activity monitors during daily life in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2013;42:1205–15.

Van Remoortel H, Raste Y, Louvaris Z, Giavedoni S, Burtin C, Langer D, Wilson F, Rabinovich R, Vogiatzis I, Hopkinson NS, Troosters T. Validity of six activity monitors in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a comparison with indirect calorimetry. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39198.

Hagstromer M, Oja P, Sjostrom M. The international physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ): a study of concurrent and construct validity. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9:755–62.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83.

Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM. The St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. Respir Med. 1991;85(Suppl B):25–31. discussion 33-27

Kon SS, Dilaver D, Mittal M, Nolan CM, Clark AL, Canavan JL, Jones SE, Polkey MI, Man WD. The clinical COPD questionnaire: response to pulmonary rehabilitation and minimal clinically important difference. Thorax. 2014;69:793–8.

Bestall JC, Paul EA, Garrod R, Garnham R, Jones PW, Wedzicha JA. Usefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 1999;54:581–6.

Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, Crapo R, Enright P, van der Grinten CP, Gustafsson P, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:319–38.

Quanjer PH, Stanojevic S, Cole TJ, Baur X, Hall GL, Culver BH, Enright PL, Hankinson JL, Ip MS, Zheng J, Stocks J. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3-95-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:1324–43.

Wanger J, Clausen JL, Coates A, Pedersen OF, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Crapo R, Enright P, van der Grinten CP, et al. Standardisation of the measurement of lung volumes. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:511–22.

Sartini C, Wannamethee SG, Iliffe S, Morris RW, Ash S, Lennon L, Whincup PH, Jefferis BJ. Diurnal patterns of objectively measured physical activity and sedentary behaviour in older men. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:609.

Watz H, Pitta F, Rochester CL, Garcia-Aymerich J, ZuWallack R, Troosters T, Vaes AW, Puhan MA, Jehn M, Polkey MI, et al. An official European Respiratory Society statement on physical activity in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2014;44:1521–37.

Yentes JM, Rennard SI, Schmid KK, Blanke D, Stergiou N. Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease walk with altered step time and step width variability as compared with healthy control subjects. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14:858–66.

Gimeno-Santos E, Frei A, Steurer-Stey C, de Batlle J, Rabinovich RA, Raste Y, Hopkinson NS, Polkey MI, van Remoortel H, Troosters T, et al. Determinants and outcomes of physical activity in patients with COPD: a systematic review. Thorax. 2014;69:731–9.

Miravitlles M, Worth H, Soler Cataluna JJ, Price D, De Benedetto F, Roche N, Godtfredsen NS, van der Molen T, Lofdahl CG, Padulles L, Ribera A. Observational study to characterise 24-hour COPD symptoms and their relationship with patient-reported outcomes: results from the ASSESS study. Respir Res. 2014;15:122.

Roche N, Small M, Broomfield S, Higgins V, Pollard R. Real world COPD: association of morning symptoms with clinical and patient reported outcomes. Copd. 2013;10:679–86.

Almagro P, Castro A. Helping COPD patients change health behavior in order to improve their quality of life. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2013;8:335–45.

Bateman ED, Chapman KR, Singh D, D'Urzo AD, Molins E, Leselbaum A, Gil EG. Aclidinium bromide and formoterol fumarate as a fixed-dose combination in COPD: pooled analysis of symptoms and exacerbations from two six-month, multicentre, randomised studies (ACLIFORM and AUGMENT). Respir Res. 2015;16:92.

Kim YJ, Lee BK, Jung CY, Jeon YJ, Hyun DS, Kim KC, Yu SK, Choi HS, Shin WH, Lee KH. Patient’s perception of symptoms related to morning activity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the SYMBOL study. Korean J Intern Med. 2012;27:426–35.

Thyregod M, Bodtger U. Coherence between self-reported and objectively measured physical activity in patients with chronic obstructive lung disease: a systematic review. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:2931–8.

Acknowledgements

We thank Steven McDowell critically reading the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Novartis with an unrestricted research grant.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Before this request, users should get permission from the local ethics committee.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Design of the study: AB, NC and CT. Data analysis: AB and MK. Data interpretation: AB, MK, NC and CT. Drafting the manuscript: AB and MK. Revision of the manuscript: NC and CT. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The local ethics committee (Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands) approved the study (protocol number NL51951.058.15) and all patients gave informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Figure S1. Number of steps in the morning, Error bars present 95% confidence intervals. Low morning symptom score: score < 17.0; high morning symptom score: score ≥ 17.0. (JPEG 192 kb)

Additional file 2:

Figure S2. Steps during each hour of the day, Low mMRC < 2 (N = 27); high mMRC ≥2 (N = 52). (JPEG 195 kb)

Additional file 3:

Table S1. Baseline characteristics for patients with and without an adverse event, Table S2 Differences in activity during the night, morning, afternoon and evening between patient with low and high morning symptom scores, N = 72, Table S3 Daily physical activity. (DOCX 41 kb)

Additional file 4:

Figure S3. Steps during the course of the day, Few morning symptoms: morning symptom score < 15; severe morning symptoms: morning symptom score ≥ 15. (JPEG 203 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

van Buul, A.R., Kasteleyn, M.J., Chavannes, N.H. et al. Physical activity in the morning and afternoon is lower in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with morning symptoms. Respir Res 19, 49 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-018-0749-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-018-0749-4