Abstract

Background

To systematically review and assess the in vivo effectiveness and safety of probiotics for prophylaxis and treating oral candidiasis.

Methods

A literature search for studies published in English until August 1, 2018 was conducted in the following databases: PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science. Randomized controlled clinical trials and experimental mouse animal model studies comparing probiotics (at any dosage and in any form) with control groups (placebo, blank control or other agents) and reporting outcomes of the prophylactic and therapeutic effects were considered for inclusion. A descriptive study and, potentially, a meta-analysis were planned.

Results

Six randomized controlled clinical trials and 5 controlled experiments of mouse animal models were included in the systematic review. Four randomized controlled clinical trials comparing a probiotics group with a placebo/blank control group in 480 elderly and denture wearers were included in the meta-analysis. The overall combined odds ratio of the (random effects) meta-analysis was 0.24 (95% CI =0.09–0.63, P < 0.01). The overall combined odds ratio of the (fixed effects) sensitivity analysis was 0.39 (95% CI =0.25–0.60, P < 0.01) by excluding a study with the smallest sample size. These analyses showed that there was a statistically significant difference in the effect of probiotics compared with the control groups in elderly and denture wearers. The remaining 2 studies compared probiotics with other agents in a population aged 18–75 years and children aged 6–14 years respectively, and were analyzed descriptively. Meta-analysis and descriptive analyses indicated that probiotics were potentially effective in reducing morbidity, improving clinical symptoms and reducing oral Candida counts in oral candidiasis. The biases of the included studies were low or uncertain. The relatively common complaints reported were gastrointestinal discomfort and unpleasant taste, and no severe adverse events were reported.

Conclusions

Probiotics were superior to the placebo and blank control in preventing and treating oral candidiasis in the elderly and denture wearers. Although probiotics showed a favorable effect in treating oral candidiasis, more evidence is required to warrant their effectiveness when compared with conventional antifungal treatments. Moreover, data on the safety of probiotics are still insufficient, and further research is needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Oral candidiasis (OC) is a fungal infection considered to be the most common oral mucosal infectious disease [1] and is mainly caused by Candida albicans. The detection rate of C. albicans in the general population is 20 to 75% [2,3,4,5]. It has also been reported that 15 to 71% of denture wearers [3, 6, 7] and 80 to 95% of HIV-infected individuals suffer from oral candidiasis [8,9,10]. The accepted treatment for oral candidiasis is the use of antifungal agents, such as nystatin, fluconazole, or miconazole. [11]. Because of adverse effects and side effects, such as the subsequent resistance of candida to antifungal agents, dysgeusia, and gastrointestinal discomfort, including nausea, vomiting and diarrhea, the clinical application of antifungal drugs can be limited [12]. Therefore, the exploration of new prophylaxis and therapeutic strategies for oral candidiasis is indicated.

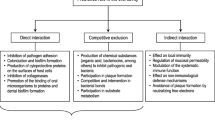

Previous studies have reported that probiotics have effects on vulvovaginal candidiasis [13], dermatophytosis [14], gastrointestinal infections [15], hypertension [16] and colorectal cancer [17,18,19]. Known mechanisms of probiotics include regulating innate and acquired immunity and releasing antioxidants and bacteriocins to restore the balance of the microbial community and the immune system [20,21,22]. Meanwhile, it is also reported that probiotics are potentially promising treatment for oral diseases such as periodontal disease, dental caries, halitosis and oral candidiasis [23].

Over the last few years, probiotics have been demonstrated to enable the regulation of the oral microbiota [24]. Studies have shown that Lactobacillus rhamnosus [25], Lactobacillus reuteri [26], etc. can reduce oral Candida counts. However, the estimated effects of probiotics in the treatment of oral candidiasis are conflicting [25,26,27]. Additionally, information on the safety of probiotics is lacking. Therefore, the aim of this review is to assess the effectiveness and safety of probiotics in the prophylaxis and treatment of oral candidiasis using a meta-analysis and systematic evaluation.

Methods

Data sources and search strategy

This systematic review was performed according to the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) [28]. Two of the authors (L.J. H and M.M. Z) independently searched the following electronic databases: PubMed, EMBASE, the Cochrane Library, and Web of Science for articles published from inception to August 1, 2018. The following terms were searched in combination: (“probiotics” OR “probiotic”) AND (“oral candidiasis” OR “oral candidiases” OR “oral moniliasis” OR “oral moniliases” OR “oral candida” OR “thrush”). Manual searches of the reference and citations of the identified studies were also conducted as a supplement.

Study selection criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (I) original studies; (II) randomized controlled clinical trials or experimental mouse animal model controlled studies; (III) studies that compared probiotics (at any dosage and in any form) with control groups (placebo, blank control or other drugs); (IV) studies that reported specific outcomes of the therapeutic effect, such as the counts of candida and/or clinical improvement; and (V) studies published in the English language. Studies written in languages other than English, review articles, letters to the editor, meeting summaries, patented inventions, unpublished articles and articles that did not have full-text available were excluded.

Data extraction

The two investigators (L.J. H and M.M. Z) independently identified the titles and abstracts that potentially met the inclusion criteria. Then, full-text articles were read for a complete assessment and determination of inclusion or exclusion. Each investigator independently performed the above steps. If the two review authors could not reach a consensus regarding inclusion, a third reviewer (Z.M. Y or A. Y) was invited to conduct an assessment and settle any disagreements. For each included article, data such as age, gender/sex, sample size, interventions, follow-up time and outcome indicators were extracted and summarized in a table format.

Risk of bias of the included studies

Three investigators (L.J. H, M.M. Z, and W.W. Z) evaluated the clinical studies based on the criteria of the Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions using Review Manager 5.2 (Cochrane IMS, Oxford, UK). The considered biases were as follows: (I) random sequence generation (selection bias); (II) allocation concealment (selection bias); (III) blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias); (IV) blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias); (V) incomplete outcome data (attrition bias); and (VI) selective reporting (reporting bias).

For studies using animal models, the quality evaluation was based on the Collaborative Approach to Meta Analysis and Review of Animal Data from Experimental Studies (CAMARADES) [29]. The considered biases were as follows: (I) sample size calculation; (II) randomization of treatment or control; (III) blinded assessment of outcome; (IV) allocation concealment; (V) use of suitable animals; (VI) avoidance of anesthetics with marked intrinsic properties; (VII) statement of control of temperature; (VIII) statement of compliance with regulatory requirements; (IX) publication in a peer-reviewed journal; and (X) statement regarding possible conflicts of interest.

Statistical analysis

Review Manager 5.2 was used to perform the meta-analyses. We assessed the therapeutic effect of probiotics on oral candidiasis by means of odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using Mantel-Haenszel statistics. Statistical heterogeneity analysis of the included studies was performed using the I2 metric. When I2 < 50%, the studies were considered to be sufficiently homogeneous, and a fixed effect model was used. In contrast, when there was heterogeneity among the studies, a random effects model was used, and sensitivity analysis was conducted to achieve homogeneity among the included studies.

For the smaller group of studies with poor homogeneity and for data provided by studies that could not be analyzed by meta-analysis, descriptive analysis and evaluation (i.e., qualitative analysis) was performed.

Results

Clinical research

Characteristics of the included studies

The number of included clinical studies was 6, which involved a total of 605 subjects (Fig. 1). The data extracted from each study are summarized in Table 1.

Four of these studies, including 480 elderly and denture wearers, compared the effects of therapy between the probiotics group and the blank or placebo group, and a meta-analysis was performed [25,26,27, 30]. The study by TY Miyazima et al. subdivided the probiotics group into the T1 probiotics group using Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM and the T2 probiotics group using L. rhamnosus Lr-32 [30]. Given the existing heterogeneity of the interventions, this study combined the T1 probiotics group and T2 probiotics group as one group in the meta-analysis.

Two of these studies were excluded in the meta-analysis and were evaluated by descriptive analysis due to the comparison of probiotics with other agents. The study by Duo Li et al. evaluated the short-term effectiveness and safety of probiotics in a population aged 18–75 years by comparing a probiotics group (received topical antifungal agents—sodium bicarbonate solution and nystatin—as well as Bifidobacterium longum, Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus) with a control group (received only topical antifungal agents) [31]. The trial by Rahul Mishra et al. compared the antimicrobial effect of probiotics in children aged 6–14 years with herbal rinse and commonly used antimicrobial agents of 0.2% chlorhexidine [32]. However, the types of probiotics contained in the probiotic product were not mentioned in the article.

Quality of the included studies

According to the Cochrane risk of bias assessment criteria, the included studies failed to achieve all seven aspects in detail. The quality evaluations of the studies are listed in Table 2. The overall risk of each type of bias is presented in Fig. 2, and the risk of each bias in each of the included studies is presented in Fig. 3. The risk of bias assessment for the included studies was conducted by 2 independent researchers (L.J. H and M.M. Z), and the consistency of the assessment results was 100%.

Effectiveness assessment

Meta-analysis was performed on 4 studies with a total of 480 subjects that compared a probiotics group with a placebo or blank control group [25,26,27, 30]. The heterogeneity analysis of these 4 studies yielded x2 = 13.41, P = 0.004, and I2 = 78%. The random effects model analysis showed that there was a statistically significant difference in the effect of probiotics for preventing and treating oral candidiasis in elderly and denture wearers compared with the control groups (OR = 0.24, 95% CI =0.09–0.63, P < 0.01; Fig. 4).

Sensitivity analysis was performed in the meta-analysis. After removing 1 study with the smallest sample size, the remaining 3 studies were of good homogeneity with an I2 value of 0% [27]. The fixed effect model analysis showed that there was a statistically significant difference in the effect of probiotics compared with the control groups in elderly and denture wearers (OR = 0.39, 95% CI =0.25–0.60, P < 0.01; Fig. 5). Thus, taken together, the meta-analysis indicated that probiotics may be potentially effective for oral candidiasis in the elderly and denture wearers.

In addition, two studies compared the effect of probiotics with other drugs, including the combination of nystatin paste and a sodium bicarbonate solution, Chinese herbal rinse and 0.2% chlorhexidine digluconate rinse [31, 32]. Although hyperemia of the probiotics group using the combination of probiotics, nystatin paste and sodium bicarbonate solution improved after 4 weeks of follow-up, it did not show significant differences compared with the control group without probiotics. However, the detection rate of Candida spp. in the probiotics group (8.2%) was significantly lower than in the control group (34.6%) in this population aged 18–75 years (P = 0.038) [31]. Therefore, probiotics helped to improve the clinical symptoms of oral candidiasis and reduce the detection rate of Candida spp. more than using antifungal drugs alone. The 0.2% chlorhexidine digluconate rinse group had the best effects in terms of decreasing the number of C. albicans colony-forming units (CFUs) per milliliter in children aged 6–14 years (P < 0.01), followed by the probiotics group (P < 0.01), and the poorest outcome was from the Chinese herbal rinse (P > 0.01) [32]. From the above information, probiotics exhibit the potential effect of inhibiting the colonization of Candida on the surface of oral mucosa and improving the clinical signs and symptoms of fungal infections.

Safety evaluation

Only 2 of the 6 studies included information about adverse events or complaints with probiotics [26, 31]. One study reported that the probiotic had no adverse events [31], while the other reported that its most common complaints were an unpleasant taste and gastric discomfort, with incidences of 6 and 2.87%, respectively, but no severe adverse events were reported [26].

Animal research

Through a literature search and screening, a total of 5 studies that met the criteria were included [33,34,35,36,37]. Table 3 lists the 5 studies and the data extracted, which included publication date, sex, age and strain of the mouse animal model, number of mice, method of candida infection, probiotic species, method of drug administration, intervention time, control group, and outcome indicators. The bias assessment of the included mouse animal model experiments is summarized in Table 4.

Because the original data of Candida colony-forming units per milliliter and symptom score could not be obtained, a descriptive analysis was performed. First, compared with the blank group, L. acidophilus, L. rhamnosus and 3 × 109 CFU/ml of Streptococcus salivarius K12 all showed the effect of reducing the Candida counts (P < 0.05) [33,34,35, 37]. In 2 studies conducted by Sanae A. Ishijima et al., 1.5 × 109 CFU/ml and 3 × 109 CFU/ml of S. salivarius K12 and 15 mg/ml and 30 mg/ml of Enterococcus faecalis all indicated an obviously significant difference from the control group (P < 0.01) [34, 36]. Second, L. rhamnosus could significantly reduce the Candida counts compared with nystatin (P < 0.05) [33]. When compared with fluconazole, a study reported that mice given 15 mg/ml of E. faecalis had a significant decrease in fungal burden, although this was not observed to be a complete cure [36]. These results showed that probiotics had an effect in reducing oral Candida counts and reducing the clinical signs and symptoms of fungal infections in animal models.

Discussion

Attempting to treat oral candidiasis with probiotics has gradually become a topic of considerable interest in research. The clinical studies and animal model experiments included in this review reported that probiotics such as L. rhamnosus [25, 27, 30, 33, 37], Propionibacterium freudenreichii [25], L. acidophilus [27, 30, 33, 35], L. reuteri [26], B. longum [31], Bifidobacterium bifidum [27], L. bulgaricus [31], S. thermophiles [31], L. fermentum [35], S. salivarius K12 [34] and heat-killed E. faecalis [36] have the effect of inhibiting the excessive growth of Candida. Although the results of studies that met the eligibility criteria appear to demonstrate that probiotics have potential antifungal effects, the types of probiotics selected in these studies were different, and some studies focused on single probiotics [26, 30], while others focused on a combination of multiple probiotics [25, 27, 31]. For example, the study by TY Miyazima et al. reported that using L. acidophilus or L. rhamnosus alone could reduce oral Candida counts [30], while the study by Hatakka et al. showed that the combined use of L. rhamnosus and P. freudenreichii can reduce the risk of high yeast counts by 75% [25]. Additionally, in 2015, Ishikawa et al. indicated that the combination of probiotics containing L. rhamnosus, L. acidophilus and B. bifidum reduced the level of Candida colonization in dentures [27]. Since the types and concentrations of probiotics varied between the studies included in this review, we were unable to determine which species of probiotics and what specific doses are optimal for treating oral candidiasis. Meanwhile, research still needs to be done on which combinations of probiotics have better curative effects and how probiotics work synergistically. It is worth noting, however, that the types of probiotics in these 5 clinical studies [25,26,27, 30, 31] and 3 mouse-model experiments [34, 35, 37] were from the genera Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium.

Of the included studies, there were studies comparing the effect of probiotics with conventional antifungal treatments [31, 32]. Duo Li et al. reported that oral local antifungal agents (2% sodium bicarbonate solution and nystatin) plus local probiotics helped to improve certain clinical conditions and reduce the detection rate of Candida spp. [31]. Moreover, a study in 2016 demonstrated that probiotic rinse was equally effective as 0.2% chlorhexidine digluconate rinse in reducing C. albicans counts after 1 week of intervention [32]. However, there is still insufficient evidence to prove that probiotics can completely replace antifungal agents in the treatment of oral candidiasis.

Of the 6 RCTs included, 3 evaluated the prophylaxis effect of probiotics in susceptible populations [25, 26, 32]. In total, in 366 elderly people from sheltered housing units and nursing homes, probiotics of L. rhamnosus, P. freudenreichii and L. reuteri were effective in reducing Candida counts [25, 26]. In 60 children with carious teeth (a predisposing factor of oral Candida carriage [38]), the prophylactic effect of probiotics on oral candidiasis was revealed [32]. The possible prophylactic mechanisms included competition with pathogenic microorganisms for nutrients and receptors [39, 40] and releasing external metabolites and producing hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), antagonizing the excessive growth of Candida [41, 42]. Based on current clinical studies, it is indicated that the prophylactic use of probiotics might potentially reduce the mobility of oral candidiasis and thus decrease the economic burden of the disease.

In addition to commonly used probiotic species, an animal experiment included in this review reported that heat-killed E. faecalis had an immunostimulatory effect in a murine model of oral candidiasis, which is beneficial for the treatment of oral candidiasis [36]. Heat-treated E. faecalis has been reported to have immunoenhancing effects that include increasing cell-mediated immunity, humoral immunity, monocyte/macrophage function, and natural killer cell activity in nonsensitized mice [43]. In 2012, an animal study aimed at the lysed E. faecalis in the murine model of allergic rhinitis suggested that E. faecalis has an immunoregulatory activity [44]. In a pilot study, living nonpathogenic E. faecalis was shown to be beneficial for the treatment of asthma [45]. However, no study has investigated the clinical effect of E. faecalis on oral candidiasis. This might open up a new research direction for the study of probiotics.

With respect to safety, the adverse events of probiotics reported in the in vivo studies included in this systematic review were gastrointestinal discomfort and unpleasant taste [26]. No severe adverse events were reported from either the clinical trials or the animal studies. However, a report issued by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) in 2011 concluded that although the existing clinical trials do not indicate an increased risk, this does not necessarily confirm the safety of probiotics in intervention studies with confidence [46]. The theoretically possible side effects of probiotics were systemic infections, deleterious metabolic activities, excessive immune stimulation in susceptible individuals, and gene transfer [47]. For instance, a study reported that a newborn with an umbilical bulge developed sepsis after a 10-day administration of Bifidobacterium breve BBG01 [48]. In contrast, a study published in 2015 indicated that probiotics are generally safe for most populations based on the preponderance of the data from clinical trials, animal studies, and in vitro studies [49]. In another study, 80 children aged 3 months to 3 years old with rotavirus diarrhea were divided into placebo and treatment groups. The treatment group given commercial sachets of Bifidobacterium did not report adverse events during or after treatment [50]. Moreover, Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and Enterococcus have been used as food additives for a long period of time [51]. It has been demonstrated that the widespread use of beverages containing probiotics such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium can reduce the prevalence of oral candidiasis in healthy individuals [52]. Thus, the reports are contradictory. Therefore, further research is still needed to confirm the safety and to evaluate adverse events related to probiotics in healthy people or patients.

Although aimed at collecting the best evidence to date, this review still had limitations. First, the inconsistency of the evaluation criteria of the clinical effects among studies might be a source of heterogeneity. The limited number of trials and subjects was also a restriction. More trials are needed to verify the results above. Second, the standard for the prophylactic and therapeutic use of probiotics has not been established, and the combination of probiotics, dosages, dosing regimens, vehicles, adverse reactions, biodynamics and cost-effectiveness of the probiotics also need to be determined. Furthermore, although probiotics are beneficial to humans, as a living biological agent, it is still necessary to consider biological tolerance and whether probiotics are suitable for various types of people, such as immunosuppressed patients, infants and pregnant women. Much still needs to be learned about this new treatment for oral candidiasis.

Conclusions

It is concluded in this systematic review that probiotics were significantly superior to the placebo and blank control in preventing and treating oral candidiasis both in clinical trials of elderly and denture wearers and in animal experiments, including inhibiting the colonization of Candida on the surface of oral mucosa and reducing the clinical signs and symptoms of fungal infections. However, although probiotics showed a favorable effect in treating oral candidiasis, more evidence is required to confirm their effectiveness when compared with conventional antifungal treatments. Moreover, although the commonly reported adverse events of probiotics were relatively mild, the evidence for safety is still insufficient, and further research is needed.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- EMBASE:

-

Excerpta medica database

- F:

-

Female

- h:

-

Hours

- M:

-

Male

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

References

Krishnan PA. Fungal infections of the oral mucosa. Indian J Dent Res. 2012;23(5):650–9.

Berdicevsky I, Ben-Aryeh H, Szargel R, Gutman D. Oral Candida in children. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;57(1):37–40.

Cumming CG, Wight C, Blackwell CL, Wray D. Denture stomatitis in the elderly. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1990;5(2):82–5.

Coronado-Castellote L, Jimenez-Soriano Y. Clinical and microbiological diagnosis of oral candidiasis. J Clin Exp Dent. 2013;5(5):e279–86.

Singh A, Verma R, Murari A, Agrawal A. Oral candidiasis: an overview. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18(Suppl 1):S81–5.

Aldred MJ, Addy M, Bagg J, Finlay I. Oral health in the terminally ill: a cross-sectional pilot survey. Spec Care Dentist. 1991;11(2):59–62.

Gendreau L, Loewy ZG. Epidemiology and etiology of denture stomatitis. J Prosthodont. 2011;20(4):251–60.

Durden FM, Elewski B. Fungal infections in HIV-infected patients. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1997;16(3):200–12.

Thompson GR, Patel PK, Kirkpatrick WR, Westbrook SD, Berg D, Erlandsen J, Redding SW, Patterson TF. Oropharyngeal candidiasis in the era of antiretroviral therapy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109(4):488–95.

Berberi A, Noujeim Z, Aoun G. Epidemiology of oropharyngeal candidiasis in human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome patients and CD4+ counts. J Int Oral Health. 2015;7(3):20–3.

Niimi M, Firth NA, Cannon RD. Antifungal drug resistance of oral fungi. Odontology. 2010;98(1):15–25.

Lopez-Martinez R. Candidosis, a new challenge. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28(2):178–84.

De Seta F, Parazzini F, De Leo R, Banco R, Maso GP, De Santo D, Sartore A, Stabile G, Inglese S, Tonon M, et al. Lactobacillus plantarum P17630 for preventing Candida vaginitis recurrence: a retrospective comparative study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;182:136–9.

Kumar S, Mahajan BB, Kamra N. Future perspective of probiotics in dermatology: an old wine in new bottle. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20(9):11.

Hayama K, Ishijima S, Ono Y, Izumo T, Ida M, Shibata H, Abe S. Protective activity of S-PT84, a heat-killed preparation of Lactobacillus pentosus, against oral and gastric candidiasis in an experimental murine model. Med Mycol J. 2014;55(3):J123–9.

Khalesi S, Sun J, Buys N, Jayasinghe R. Effect of probiotics on blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Hypertension. 2014;64(4):897–903.

Wang S, Zhang L, Shan Y. Lactobacilli and colon carcinoma--a review. Wei Sheng Wu Xue Bao. 2015;55(6):667–74.

Zitvogel L, Galluzzi L, Viaud S, Vetizou M, Daillere R, Merad M, Kroemer G. Cancer and the gut microbiota: an unexpected link. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(271):271.

Shida K, Nomoto K. Probiotics as efficient immunopotentiators: translational role in cancer prevention. Indian J Med Res. 2013;138(5):808–14.

Sobko T, Huang L, Midtvedt T, Norin E, Gustafsson LE, Norman M, Jansson EA, Lundberg JO. Generation of NO by probiotic bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41(6):985–91.

Bengmark S. Bioecologic control of the gastrointestinal tract: the role of flora and supplemented probiotics and synbiotics. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2005;34(3):413–36.

Servin AL. Antagonistic activities of lactobacilli and bifidobacteria against microbial pathogens. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2004;28(4):405–40.

Meurman JH, Stamatova IV. Probiotics: evidence of Oral health implications. Folia Med (Plovdiv). 2018;60(1):21–9.

Pham LC, van Spanning RJ, Roling WF, Prosperi AC, Terefework Z, Ten CJ, Crielaard W, Zaura E. Effects of probiotic Lactobacillus salivarius W24 on the compositional stability of oral microbial communities. Arch Oral Biol. 2009;54(2):132–7.

Hatakka K, Ahola AJ, Yli-Knuuttila H, Richardson M, Poussa T, Meurman JH, Korpela R. Probiotics reduce the prevalence of oral candida in the elderly--a randomized controlled trial. J Dent Res. 2007;86(2):125–30.

Kraft-Bodi E, Jorgensen MR, Keller MK, Kragelund C, Twetman S. Effect of probiotic Bacteria on Oral Candida in frail elderly. J Dent Res. 2015;94(9 Suppl):181S–6S.

Ishikawa KH, Mayer MP, Miyazima TY, Matsubara VH, Silva EG, Paula CR, Campos TT, Nakamae AE. A multispecies probiotic reduces oral Candida colonization in denture wearers. J Prosthodont. 2015;24(3):194–9.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700.

Sena E, van der Worp HB, Howells D, Macleod M. How can we improve the pre-clinical development of drugs for stroke? Trends Neurosci. 2007;30(9):433–9.

Miyazima TY, Ishikawa KH, Mayer M, Saad S, Nakamae A. Cheese supplemented with probiotics reduced the Candida levels in denture wearers-RCT. Oral Dis. 2017;23(7):919–25.

Li D, Li Q, Liu C, Lin M, Li X, Xiao X, Zhu Z, Gong Q, Zhou H. Efficacy and safety of probiotics in the treatment of Candida-associated stomatitis. Mycoses. 2014;57(3):141–6.

Mishra R, Tandon S, Rathore M, Banerjee M. Antimicrobial efficacy of probiotic and herbal Oral rinses against Candida albicans in children: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2016;9(1):25–30.

Matsubara VH, Silva EG, Paula CR, Ishikawa KH, Nakamae AE. Treatment with probiotics in experimental oral colonization by Candida albicans in murine model (DBA/2). Oral Dis. 2012;18(3):260–4.

Ishijima SA, Hayama K, Burton JP, Reid G, Okada M, Matsushita Y, Abe S. Effect of Streptococcus salivarius K12 on the in vitro growth of Candida albicans and its protective effect in an oral candidiasis model. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78(7):2190–9.

Elahi S, Pang G, Ashman R, Clancy R. Enhanced clearance of Candida albicans from the oral cavities of mice following oral administration of Lactobacillus acidophilus. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;141(1):29–36.

Ishijima SA, Hayama K, Ninomiya K, Iwasa M, Yamazaki M, Abe S. Protection of mice from oral candidiasis by heat-killed enterococcus faecalis, possibly through its direct binding to Candida albicans. Med Mycol J. 2014;55(1):E9–E19.

Leao M, Tavares T, Goncalves ESC, Dos SS, Junqueira JC, de Oliveira LD, Jorge A. Lactobacillus rhamnosus intake can prevent the development of candidiasis. Clin Oral Investig. 2018;22(7):2511–8.

Raja M, Hannan A, Ali K. Association of oral candidal carriage with dental caries in children. Caries Res. 2010;44(3):272–6.

Vicariotto F, Del PM, Mogna L, Mogna G. Effectiveness of the association of 2 probiotic strains formulated in a slow release vaginal product, in women affected by vulvovaginal candidiasis: a pilot study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46(Suppl):S73–80.

Ujaoney S, Chandra J, Faddoul F, Chane M, Wang J, Taifour L, et al. In vitro effect of over-the-counter probiotics on the ability of Candida albicans to form biofilm on denture strips. J Dent Hyg. 2014;88(3):183–9.

Kheradmand E, Rafii F, Yazdi MH, Sepahi AA, Shahverdi AR, Oveisi MR. The antimicrobial effects of selenium nanoparticle-enriched probiotics and their fermented broth against Candida albicans. Daru. 2014;22:48.

Verdenelli MC, Coman MM, Cecchini C, Silvi S, Orpianesi C, Cresci A. Evaluation of antipathogenic activity and adherence properties of human Lactobacillus strains for vaginal formulations. J Appl Microbiol. 2014;116(5):1297–307.

Takashi S, Yunqing C, Lei C, Chie M, Kazutake F, Yoshihisa K, et al. Immunomodulation effects of heat-treated Enterococcus faecalis FK-23(FK-23) in mice. Journal of Nanjing Medical University. 2009;23(3):173–6.

Zhu L, Shimada T, Chen R, Lu M, Zhang Q, Lu W, Yin M, Enomoto T, Cheng L. Effects of lysed Enterococcus faecalis FK-23 on experimental allergic rhinitis in a murine model. J Biomed Res. 2012;26(3):226–34.

Stockert K, Schneider B, Porenta G, Rath R, Nissel H, Eichler I. Laser acupuncture and probiotics in school age children with asthma: a randomized, placebo-controlled pilot study of therapy guided by principles of traditional Chinese medicine. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2007;18(2):160–6.

Hempel S, Newberry S, Ruelaz A, Wang Z, Miles JN, Suttorp MJ, et al. Safety of probiotics used to reduce risk and prevent or treat disease. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2011;(200):1–645.

Marteau P. Safety aspects of probiotic products. Scand J Nutr. 2001;45(1):22–4.

Ohishi A, Takahashi S, Ito Y, Ohishi Y, Tsukamoto K, Nanba Y, Ito N, Kakiuchi S, Saitoh A, Morotomi M, et al. Bifidobacterium septicemia associated with postoperative probiotic therapy in a neonate with omphalocele. J Pediatr. 2010;156(4):679–81.

Doron S, Snydman DR. Risk and safety of probiotics. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(Suppl 2):S129–34.

Narayanappa D. Randomized double blinded controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of Bifilac in patients with acute viral diarrhea. Indian J Pediatr. 2008;75(7):709–13.

Saarela M, Mogensen G, Fonden R, Matto J, Mattila-Sandholm T. Probiotic bacteria: safety, functional and technological properties. J Biotechnol. 2000;84(3):197–215.

Mendonca FH, Santos SS, Faria IS, Goncalves ESC, Jorge AO, Leao MV. Effects of probiotic bacteria on Candida presence and IgA anti-Candida in the oral cavity of elderly. Braz Dent J. 2012;23(5):534–8.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Xie Shang of Peking University School and hospital of Stomatology and the statisticians from Department of Public Health, Peking University Health Science Center for helping us revising the manuscript, and the native English speaking scientists of American Journal Experts for editing our manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 81570985).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZY and LH designed the study. LH, MZ and WZ collected and analyzed data. LH wrote the manuscript. ZY and AY revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, L., Zhou, M., Young, A. et al. In vivo effectiveness and safety of probiotics on prophylaxis and treatment of oral candidiasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health 19, 140 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-019-0841-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-019-0841-2