Abstract

Background

Oral lichen planus (OLP) is a chronic inflammatory oral mucosal disease in which comprehensive inflammation-related cytokines are involved. These cytokines are commonly produced by immune cells and specific nonimmune cells including keratinocytes, endothelial cells and fibroblasts. This raises the question of whether fibroblasts in OLP lesions contribute to the inflammatory process upon inflammatory simulation.

Methods

Primary cultured Oral lichen-planus-associated fibroblasts (OLP AFs, n = 5) and normal buccal mucosal fibroblasts (NFs, n = 5) were examined by immunohistochemistry, Western blotting and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reactions (RT-PCR). Various inflammatory mediators were evaluated with a multiplex assay. Differences among groups were assessed using a Student’s test or repeated measures one-way ANOVA, as appropriate.

Results

OLP AFs express significantly higher levels of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) than NFs, indicating the presence of myofibroblasts. Myofibroblasts secrete Interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) in response to Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide (pg. LPS).

Conclusion

OLP AFs demonstrated α-SMA expression and secreted pro-inflammatory cytokines in response to pg. LPS stimulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Oral lichen planus (OLP) is a chronic inflammatory oral mucosal disease with the potential for malignant transformation [1]. The prevalence of OLP varies from 0.5 to 4% in the general population [2], and the malignant transformation rate is 0–2%. The clinical presentation of OLP involves a ranges from asymptomatic white keratotic lesions to painful erosions and ulcerations, with three distinctive clinical forms: reticular, erosive, and atrophic. Up to now, diagnosis of malignant transformation have been performed with biopsies. The histology of OLP is characterized by a dense subepithelial lympho-histiocytic infiltrate, increased numbers of intra-epithelial lymphocytes, and degeneration of basal keratinocytes.Degenerating basal keratinocytes form colloid bodies that appear as homogenous eosinophilic globules [1] In retrospective studies of Chinese cases, the erosive form was the most likely type to develop into oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) [3,4,5]. Additionally, increased levels of interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, IL-4, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and other cytokines are more closely associated with the erosive form than the reticular and atrophic forms [6,7,8]. Although the pathogenesis is not completely clear, immune and inflammatory factors are thought to play crucial roles in the development of OLP [9]. Aberrant production of many inflammatory mediators occurs in OLP lesions. Cytokines and chemokines, including ILs [10], transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), IFN-γ and TNF-α [11,12,13], have been strongly implicated.

In the environment of a dysregulated network of cytokines, fibroblasts are likely to be transformed into myofibroblasts, and the central feature of these cells in the activated state is the acquisition of α-smooth muscle fibrin [14, 15]. In healthy mucosa, MFs are absent from the epithelial and stromal cell populations. In OSCC, the stroma contains MFs among the malignant epithelial cells, which regulate the proliferation and apoptosis of the epithelia. In advanced oral submucous fibrosis (OSF), MFs are subjacent to the epithelium and secrete collagen I [16, 17]. In cyclosporine A-induced gingival overgrowth and hereditary gingival fibromatosis of connective tissue, intense α-SMA staining is observed, and MFs contribute to fibrosis by secreting several inflammatory cytokines [18, 19]. MFs are a rich source of chemokines, cytokines, and extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, which are involved in neoplasms and some inflammatory processes. The dynamic role of MFs in OSCC, OLK and OSF has been reported in previous studies [10]. However, no evidence exists of a relationship between MFs and OLP.

The original morphologic characterization of myofibroblasts by electron microscopy showed them to have numerous well-formed cytoskeletal microfilaments. These microfilaments were subsequently found to be composed of actin filaments and smooth muscle “specific” actin. The presence of actin stress fibers was similar to that seen in smooth muscle cells, but these cells also retained typical fibroblast features [20].

A large body of evidence suggests that gingival fibroblasts can react to various stimuli by releasing cytokines and chemokines, which ultimately play important roles in the inflammatory response [21].

We hypothesized that OLP fibroblasts are transformed into myofibroblasts and contribute to the inflammatory process in OLP lesions.

Materials and methods

Specimens

The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Stomatology Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, (No. KY2017019, Guangzhou 510,140, China). Informed consent was obtained from each patient. Sections of human mucosa (n = 5) were obtained from mucosa discarded during biopsies. Normal healthy mucosa was obtained from samples discarded during plastic surgery at the Stomatology Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University.

Patients were eligible for inclusion if they (1) were between 18 and 50 years old and (2) had a diagnosis consistent with erosive OLP without epithelial dysplasia. Patients were excluded if they (1) had severe systemic diseases, (2) received antibiotics or other medicines in the previous 4 weeks, or (3) had other oral mucosal diseases. Patient information for the OLP and normal specimens is shown in Table 1.

Primary culture

Freshly resected specimens were washed with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (BOSTER, AR0030, CA) containing 10% penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine (100X) (Gibco, 10,378,016, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) before being minced into 1-mm3 fragments. These fragments were cultured in DMEM medium (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (10,099,141, Gibco) at 37 °C with 5% CO2. This medium was used for carcinoma-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and NFs [22,23,24]. Cultured cells at passages 3–6 were used.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The samples were rinsed with PBS and fixed overnight in 3% glutaraldehyde at 4 °C. Next, the samples were dehydrated using the following ethanol gradient: 30, 50, 70, 95, and 100%. Then, the samples were dehydrated with xylene and air-dried at room temperature. Subsequently, the specimens were coated with gold and examined by SEM (HITACHI-S-3400 N, Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The obtained images were processed using Adobe Photoshop CS6 software (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

Immunohistochemistry and immunocytochemistry

Immunohistochemistry: Mucosal sections were processed for histology. The Diva Decloaker reagent was used for antigen retrieval in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues. α-SMA and vimentin were detected with monoclonal rabbit anti-α-SMA (ab32575, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) (1:300) and anti-vimentin (ab92547, Abcam) (1:300), followed by treatment with goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (HRP, ab6721, Abcam) and diaminobenzidine.

Immunocytochemistry: Primary cells were seeded on glass coverslips in six-well plates. At least five randomly selected visual fields of the immunostained cells were examined under a light microscope (Leica, DM4000, Tokyo, Japan). The obtained images were compiled using Adobe Photoshop CS6 software.

Immunofluorescence staining was performed on paraffin-embedded sections of normal and diseased human oral mucosal specimens. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies to CD31 (ab28364, Abcam) (1:25) or mouse monoclonal antibodies to α-SMA (ab7817, Abcam) (1:200) were applied overnight, followed by incubation with goat anti-rabbit Cy2 (111–225-144, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) or a mouse monoclonal antibody to α-SMA (ab205719, Abcam) (1:250), respectively. Cells were examined with a fluorescence (Leica, DM4000, Instruments, Melville, NY) or confocal (Leica, tcssp8, NY) microscope.

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

RNA was harvested from primary cultures established from five different buccal mucosa samples using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and reverse transcribed into first-strand cDNA with the gDNA eraser (RR047A, TAKARA) transcription system. RT-PCR was performed with SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ II (TAKARA, RR820A) using a Bio-Rad system, and GAPDH and β-actin were used as internal controls. Gene expression was quantified relative to the internal controls. All primers are listed in Table 2. The experiments were repeated a total of three times.

Western blotting

Primary cells were lysed with RIPA buffer and a proteinase inhibitor mixture (PMSF). Nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins were separated using a nuclear and cytoplasm protein extraction kit (78,833, Thermo Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The protein concentration was assessed using a Multiskan instrument (Thermo, Multiskan Mk3). Total proteins were electrophoresed on 12% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto polyscreen PVDF transfer membranes (Immobilon-P PVDF Membrane, Merck Millipore). Membranes were blocked with 5% (w/v) nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.1% Tween 20 for 1 h at room temperature and incubated overnight with primary anti-α-SMA (ab32575, Abcam) (1:5000), anti-vimentin (ab92547, Abcam) (1:5000), anti-TLR2 (ab16894, Abcam) (1:1000) and anti-TLR4 (ab22048, Abcam) (1:1000) at 4 °C. After washing, an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody was added for 1 h at 37 °C. Detection was performed with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL), and blots were quantified by densitometry using the accompanying computerized image analysis program (Image Tool).

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation

Cells grown in 12-well plates (5.0 × 104 cells/well) were treated with the Toll-like receptor ligand pg. LPS (Invivogen) at a concentration of 10 ng/ml for 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24 or 48 h, and the corresponding supernatants were collected. PBS was used as a control.

Human 9-plex assay

Conditioned media samples of LPS-treated cells were submitted in triplicate for Human 9-Plex assay testing to the USC Beckman Center Immune Monitoring Core Lab. Secreted cytokines and chemokines were analyzed with the Bio-Plex suspension array system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) using a Q-Plex Human 9-Plex Kit (110449HU, Quansys Biosciences, USA) to evaluate IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IFN-γ, and TNF-α concentrations. Experiments were repeated a total of three times.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and cytokine assay

Conditioned media samples from treated cells were collected, passed through a 0.45-μm filter to remove cell debris, aliquoted, and frozen at − 20 °C. An ELISA Kit (Abcam, ab46042, UK) was used to evaluate IL-6 concentrations at 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24 and 48 h, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cytokine levels in each sample were determined based on a standard curve generated by the recombinant proteins provided with the kits.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using Prism statistical software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Differences among groups were assessed using a two-sided Student’s test or repeated measures one-way ANOVA, as appropriate. The results are expressed as means±SEM. *** P < 0.01; ** 0.01 ≤ P < 0.05; and NS P ≥ 0.05.

Results

OLP buccal mucosa contains stromal cells expressing α-SMA

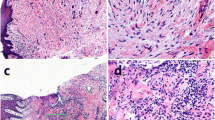

Immunostaining demonstrated expression of α-SMA in spindle-shaped cells adjacent to the OLP mucosal epithelium (Fig. 1a), which was not found in normal buccal mucosa (Fig. 1b). α-SMA expression was also observed in endothelial cells forming blood vessels.

Immunohistochemical and Immunostaining for α-SMA in OLP and oral normal buccle tissue (NBT). α-SMA-positive stromal cells (black arrows) located in the subepithelial layer showing cytoplasmatic immunostaining (a) were considered as a marker of myofibroblasts. α-SMA(+)CD31(−) spindle-shaped cells(white arrows) around bm consisted with myofibroblast’s identification.Meanwhile, α-SMA(+)CD31(+) vascular endothelial cell(yellow arrows) formed as vessels (c) α-SMA staining was not observed in NBT subepithelium (b and d) (20-fold magnification). epi = epithelial. bm = basement membrane

To determine whether the α-SMA expression was in MFs or endothelial cells, we performed immunostaining for α-SMA and CD31. Each DAPI-stained nucleus was evaluated for expression of α-SMA and CD31. Confocal microscopy demonstrated that in OLP mucosa, spindle-shaped cells around the basement membrane occasionally expressed the MF marker α-SMA (Fig. 1c). Endothelial cells forming blood vessels were also α-SMA+ and were distinguished from spindle-shaped cells by their circular configuration and the specific endothelial marker CD31. Immunofluorescence of normal mucosa did not show α-SMA staining near the squamous epithelium (Fig. 1d).

Primary cultured OLP AFs express α-SMA in vitro

After plating, the heterogeneous cells adhered to the bottom of the plate (Fig. 2a). Adherent mucosal stromal cells retained a spindle-shaped morphology (Fig. 2b).

Within 7–21 days, the mixed cell suspension flattens out and adheres to the plate bottom, followed by an outgrowth of spindle-shaped cells (a and b). Scanning electron microscopic of the primary culture. Large, polygonal shape of AF (c) with bundles of fibrils resembling those of smooth muscle arranged parallel to the axis of the cell in the cytoplasm (e), and long and thin spindle shape of NF (d) can be observed

Proliferating cells from the OLP region were large and polygonal in shape (Fig. 2c) and the cells from NF group present long and thin spindle shape (Fig. 2d). Bundles of packed fibrils resembling smooth muscle developed within the cytoplasm and were usually arranged parallel to the axis of the cell (Fig. 2e).

Immunohistochemical staining for intracellular cytoskeletal proteins demonstrated that OLP mucosal stromal cells in primary culture coexpressed α-SMA and vimentin (Fig. 3a and b); primary cultured cells from normal mucosa lacked α-SMA but expressed vimentin (Fig. 3c and d).

OLP mucosal stromal cells in primary culture coexpress α-SMA and vimentin (a and b). Primary cultured cells from normal mucosa lacked α-SMA expression but expressed vimentin (c and d). Expression of α-SMA and vimentin mRNA harvested from AF and NF was evaluated by quantitative RT-PCR. mRNA expression of α-SMA from AF was significantly higher than that of NF. Vimentin expression showed no significant difference between the groups (p = 0.471) (e). Western blot analysis performed with total cellular proteins from NF and AF clones. AF expressed high levels of α-SMA, whereas fibroblast clones lacked expression. NF and AF showed no significant difference in vimentin expression. GAPDH was used as an internal control (f)

The relative mRNA expression of α-SMA in OLP AFs was significantly higher than in NFs (*** P < 0.01), whereas no significant difference in vimentin was observed between the OLP AFs and NFs (P = 0.221) (Fig. 3e) Immunoblot suggested that AFs express higher α-SMA levels than NFs (Fig. 3f).

Increased secretion of inflammation-related cytokines by OLP AFs in response to LPS stimulation

Human 9-Plex cytokine/chemokine screening demonstrated a continuous increase in the secretion of IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α from 0 to 8 h after pg. LPS stimulation (Fig. 4a). The expression began to significantly decline at 12 h, and no difference was found at the 48-h time point compared to 0 h. Statistically significant decreases in IL-1β and IL-10 were detectable after 2 and 4 h (Fig. 4b). No significant differences were detected in IL-1-α, IL-2, IL-4, and IFN-γ at any timepoint in response to pg. LPS stimulation (Fig. 4c).

IL-6 was detected in OLP AF- and control-conditioned media using ELISA. IL-6 was continuously increased, and significant differences in IL-6 were observed between OLP AF- and control-conditioned media at 4, 8, and 12 h (Fig. 4d).

Four hours after LPS stimulation, we observed a significant increase in IL-6 in OLP AF-conditioned media (Table 3). Maximal IL-6 expression occurred after 8 h, with a nearly 250-fold increase compared to the level at 0 h, which began to significantly decline at 12 h compared to the concentration at 4 h.

Discussion

OLP is a chronic inflammatory condition that involves the oral mucosal stratified squamous epithelium and the underlying lamina propria. The prevailing theories of OLP pathogenesis revolve around dysregulated T cell responses to exogenous triggers vs. a dysregulated autoimmune response to autologous keratinocyte antigens [25].

Nonspecific inflammation is a type of chronic inflammation that exhibits three main characteristics: (1) inflammatory cell infiltration; (2) tissue destruction; and (3) a repair response [26]. We consider OLP to be a model of nonspecific inflammation due to the following pathological and micrographic features: (1) liquefaction and degeneration of basal epithelial cells and band infiltration of superficial lymphocytes in the lamina propria [27]; (2) inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, and MMPs that potentially cause a disordered arrangement of epithelial basal cells and the fracture of junctions between the stratum basale and basement membrane [28]; and (3) an increased number of Langerhans cells and mast cells in OLP lesions [29]. Although a large number of literatures have shown that pro-inflammatory cytokines are increased in OLP lesions, saliva and serum, its mechanism is still unclear.

Myofibroblasts are a highly specialized set of differentiated cells that play a prominent role during the body’s response to injury but can also contribute pathologically to inflammatory conditions such as fibrosis and cancer [30]. A key feature of myofibroblasts is expression of α-SMA.With improved diagnostics, lineage tracing studies, and genetic tools, a number of myofibroblast precursors have been identified, including fibroblasts, epithelial and endothelial cells via epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndoMT), resident mesenchymal progenitor cells,adipose tissue cells, and bone-marrow-derived circulating fibrocytes . [31] In previous studies, immunohistochemical observations demonstrated no expression of α-SMA in the epithelium and subepithelial tissue of and OLP mucosa, whether there are MFs located in OLP lesion is controversial.We immunostained the protein maker α-SMA and find that OLP buccal mucosa contains stromal cells expressing α-SMA.To identify these stromal cells, Immunohistochemical staining was used combined with observation of the morphology of the isolated cells.

Recently, several studies have suggested that microorganisms may trigger or be responsible for sustaining or exacerbating the chronic course of OLP [32,33,34]. Epithelial barrier dysfunction may precede intracellular infection of basal epithelial cells with bacteria, virus, or possibly fungus. In contrast to patients with oral mucosa and periodontal health, the expression of periodontitis related bacteria including porphyromonas gingivalis increased in the saliva of OLP patients and was positively correlated with the severity score.So We treated cells by LPS from P. gingivalis and Elisa to detect the Soluble cytokines in the collected supernatant. We found that LPS from P. gingivalis contributes to the over-production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in vitro, which may represent new evidence for the potential roles of microbial factors in the pathogenesis of OLP.

ILs are a group of cytokines with multiple roles in nearly all aspects of inflammation and immunity, including immune cell proliferation, differentiation, maturation and activation [35]. IL-6, IL8 and TNF-α are mainly secreted by antigen-presenting cells, including dendritic cells, macrophages and B cells, but are also expressed by a variety of nonimmune cells. Increases in IL-6, IL8 and TNF-α expression have been reported previously in OLP lesions and serum, especially the erosive forms [8].

There is no credible evidence can prove that the fibroblasts from OLP secret pro-inflammatory cytokines.According to our results,fibroblast from the normal buccal secret feebler pro-inflammatory cytokines than myofibroblast. In the model of microbial infection established in vitro, what cellular mechanism of pg.lps induces MFB to produce and release pro-inflammatory cytokines is be worth searching.

Conclusion

-

1.

A subset of fibroblasts in OLP lesions are transformed into myofibroblasts.

-

2.

OLP AFs secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines in response to microorganismal infection.

Abbreviations

- DMEM:

-

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- FBS:

-

Fetal bovine serum

- IFN-γ:

-

interferon-γ

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- LPS:

-

Lipopolysaccharide

- Pg.:

-

Porphyromonas gingivalis

- TLR:

-

Toll-like receptor

- TNF-α:

-

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- TNF-α:

-

tumor necrosis factor-α

- α-SMA:

-

α-smooth muscle actin

References

Sugerman PB, Savage NW, Walsh LJ, Zhao ZZ, Zhou XJ, Khan A, Seymour GJ, Bigby M. The pathogenesis of oral lichen planus. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2002;13(4):350–65.

Haqiqi MA, Pourmoshir N, Bereshneh AH. Clinical and genetic aspects of oral lichen planus. Int J Biomed Adv Res. 2016;7(6):251.

Xue JL, Fan MW, Wang SZ, Chen XM, Li Y, Wang L. A clinical study of 674 patients with oral lichen planus in China. J Oral Pathol Med. 2005;34(8):467–72.

Fang M, Zhang W, Chen Y, He Z. Malignant transformation of oral lichen planus: a retrospective study of 23 cases. Quintessence Int. 2009;40(3):235–42.

Shen ZY, Liu W, Zhu LK, Feng JQ, Tang GY, Zhou ZT. A retrospective clinicopathological study on oral lichen planus and malignant transformation: analysis of 518 cases. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2012;17(6):e943–7.

Monteiro BV, Pereira Jdos S, Nonaka CF, Godoy GP, da Silveira EJ, Miguel MC. Immunoexpression of Th17-related cytokines in oral lichen planus. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2015;23(6):409–15.

Abdel-Haq A, Kusnierz-Cabala B, Darczuk D, Sobuta E, Dumnicka P, Wojas-Pelc A, Chomyszyn-Gajewska M. Interleukin-6 and neopterin levels in the serum and saliva of patients with lichen planus and oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med. 2014;43(10):734–9.

Lu R, Zhang J, Sun W, Du G, Zhou G. Inflammation-related cytokines in oral lichen planus: an overview. J Oral Pathol Med. 2015;44(1):1–14.

Ma H, Wu Y, Yang H, Liu J, Dan H, Zeng X, Zhou Y, Jiang L, Chen Q. MicroRNAs in oral lichen planus and potential miRNA-mRNA pathogenesis with essential cytokines: a review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2016;122(2):164–73.

Bagul N, Ganjre A, Goryawala SN, Kathariya R, Dusane S. Dynamic role of myofibroblasts in oral lesions. World J Clin Oncol. 2015;6(6):264–71.

Chen Y, Zhang W, Geng N, Tian K, Jack Windsor L. MMPs, TIMP-2, and TGF-beta1 in the cancerization of oral lichen planus. Head Neck. 2008;30(9):1237–45.

Khan A, Farah CS, Savage NW, Walsh LJ, Harbrow DJ, Sugerman PB. Th1 cytokines in oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med. 2003;32(2):77–83.

Simark-Mattsson C, Bergenholtz G, Jontell M, Eklund C, Seymour GJ, Sugerman PB, Savage NW, Dahlgren UI. Distribution of interleukin-2, −4, −10, tumour necrosis factor-alpha and transforming growth factor-beta mRNAs in oral lichen planus. Arch Oral Biol. 1999;44(6):499–507.

Eyden B. The myofibroblast: phenotypic characterization as a prerequisite to understanding its functions in translational medicine. J Cell Mol Med. 2008;12(1):22–37.

Wilson SE. Corneal myofibroblast biology and pathobiology: generation, persistence and transparency. Exp Eye Res. 2012;99(1):78–88.

Jayaraj G, Sherlin HJ, Ramani P, Premkumar P, Natesan A. Stromal myofibroblasts in oral squamous cell carcinoma and potentially malignant disorders. Indian J Cancer. 2015;52(1):87–92.

Gandhi P, Prasad UC. Evaluation of myofibroblasts in oral submucous fibrosis and oral squamous cell carcinoma: the pathogenesis and correlation. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2017;14(5):314–20.

Arora H, Madapusi BT, Ramamurti A, Narasimhan M, Periasamy S, Rao SR. Immunohistochemical localization of epithelial mesenchymal transition markers in cyclosporine a induced gingival overgrowth. J Clin Diagnos Res: JCDR. 2016;10(8):ZC48–52.

Bitu CC, Sobral LM, Kellermann MG, Martelli-Junior H, Zecchin KG, Graner E, Coletta RD. Heterogeneous presence of myofibroblasts in hereditary gingival fibromatosis. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33(6):393–400.

Sandbo N, Smolyaninova LV, Orlov SN, Dulin NO. Control of Myofibroblast differentiation and function by cytoskeletal signaling. Biochem Biokhim. 2016;81(13):1698–708.

Azevedo FP, Morandini AC, Sipert CR, Dionísio TJ, Santos CF, Damante CA, de Rezende ML, Sant AC a, Greghi SL. Palatal mucosa derived fibroblasts present an adaptive behavior regarding cytokine secretion when grafted onto the gingival margin. Bmc Oral Health. 2014;14(1):1–9.

Liu Y, Hu T, Shen J, Li SF, Lin JW, Zheng XH, Gao QH, Zhou HM. Separation, cultivation and biological characteristics of oral carcinoma-associated fibroblasts. Oral Dis. 2006;12(4):375–80.

Meng W, Wu Y, He X, Liu C, Gao Q, Ge L, Wu L, Liu Y, Guo Y, Li X, et al. A systems biology approach identifies effective tumor-stroma common targets for oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2014;74(8):2306–15.

Sobral LM, Zecchin KG, Nascimento de Aquino S, Lopes MA, Graner E, Coletta RD. Isolation and characterization of myofibroblast cell lines from oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2011;25(4):1013–20.

Kurago ZB. Etiology and pathogenesis of oral lichen planus: an overview. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2016;122(1):72–80.

Nogueira PA, Carneiro S, Ramos-e-Silva M. Oral lichen planus: an update on its pathogenesis. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54(9):1005–10.

Payeras MR, Cherubini K, Figueiredo MA, Salum FG. Oral lichen planus: focus on etiopathogenesis. Arch Oral Biol. 2013;58(9):1057–69.

Paul M, Shetty DC. Analysis of the changes in the basal cell region of oral lichen planus: an ultrastructural study. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol: JOMFP. 2013;17(1):10–6.

Vered M, Fürth E, Shalev Y, Dan D. Inflammatory cells of immunosuppressive phenotypes in oral lichen planus have a proinflammatory pattern of expression and are associated with clinical parameters. Clin Oral Investig. 2013;17(5):1365–73.

Otranto M, Sarrazy V, Bonte F, Hinz B, Gabbiani G, Desmouliere A. The role of the myofibroblast in tumor stroma remodeling. Cell Adhes Migr. 2012;6(3):203–19.

Hinz B. Myofibroblasts. Exp Eye Res. 2016;142:56–70.

Zeng Q, Yang X, Chen X, Xia J, Cheng B, Tao X. Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide induces over production of CC chemokine ligand 2 via toll-like receptor-4 in oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med. 2018;47(2):166–72.

He Y, Gong D, Shi C, Shao F, Shi J, Fei J. Dysbiosis of oral buccal mucosa microbiota in patients with oral lichen planus. Oral Dis. 2017;23(5):674–82.

Mizuki H, Abe R, Kogi S, Mikami T. Immunohistochemical detection of mycoplasma salivarium in oral lichen planus tissue. J Oral Pathol Med. 2017;46(8):649–56.

Brocker C, Thompson D, Matsumoto A, Nebert DW, Vasiliou V. Evolutionary divergence and functions of the human interleukin (IL) gene family. Hum Genomics. 2010;5(1):1–26.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Zhiqiang Weng and Changbao Huo for their help with laboratory work.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81271159 and 81500850), the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province (2016ZC0149), and the China Scientific Research Program of Traditional Chinese Medicine Bureau of Guangdong Province (20152162).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its Additional files 1, 2, and 3.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LW, YY and XX performed the clinical examinations, collected specimens and conducted the experiments. TY and XW performed the pathologic diagnosis, analyzed and interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. WM, HYW GL and LG designed and supervised the study and edited and gave final approval for the manuscript to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the research and ethical committee of the Stomatology Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, (No. KY2017019, Guangzhou 510,140, China), and written consent was acquired from the patients.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

The detected concentrations of IL1-α, IL1-β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10 IFN-γ and TNF-α from AF- and NF-conditioned media at the 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24, and 48 h time points. (CSV 15 kb)

Additional file 2:

Immunoblot of TLR2 and TLR4 expressed by AFs according to the time point. (TIF 266 kb)

Additional file 3:

Immunofluorescence of IL-6, TLR2, and TLR4 expressed by AFs after 8 h of pg.LPS stimulation. (TIF 274 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, L., Yang, Y., Xiong, X. et al. Oral lichen-planus-associated fibroblasts acquire myofibroblast characteristics and secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines in response to Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide stimulation. BMC Oral Health 18, 197 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-018-0656-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-018-0656-6