Abstract

Background

Recently awareness of the importance of Aspergillus colonization in the airway of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was rising. The aim of this study was to investigate the clinical features and short-term outcomes of COPD patients with Aspergillus colonization during acute exacerbation.

Methods

A pair-matched retrospective study on patients presenting with COPD exacerbation was conducted from January 2014 to March 2016 in Beijing Hospital, China.

Results

Twenty-three patients with Aspergillus colonization and 69 patients as controls, diagnosed of COPD exacerbation, were included in this study at a pair-matched ratio of 1:3. In stable stage, the percentage of patients with high-dose corticosteroids inhalation in the Aspergillus colonization group is higher than that of in control group (65.5% vs 33.3%, p = 0.048). Multivariate analysis showed that corticosteroids use was the risk factor for isolation of Aspergillus. In acute exacerbation stage, patients in Aspergillus colonization group received higher dose of inhaled corticosteroids and more types of antibiotics than control group. The short-time outcome hinted that the remission time and the duration of hospitalization were longer in the Aspergillus colonization group than in the control group (remission time: 11 ± 4 days vs 7 ± 4 days, p = 0.001; duration: 15 ± 5 days vs 12 ± 4 days, p = 0.011).

Conclusions

Aspergillus colonization in the lower respiratory tract of COPD patients showed typical clinical manifestations, affected their short time outcome and provided a dilemma of clinical treatment strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is rapidly growing and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, which increases economic health burden [1,2,3]. COPD is characterized by irreversible airflow obstruction with underlying emphysema and small airway obliteration, which commonly co-exist. Pathogenic microorganisms, such as bacteria, are commonly colonized in the airways of COPD patients, possibly contributing to increased airway inflammation, and have been implicated in COPD exacerbations [4,5,6]. However, fungal colonization and its potential role in acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) are poorly understood.

Aspergillus spp. is a ubiquitous fungus in the environment with high sporulation capacity [7, 8]. After Aspergillus sporulates, conidia with a diameter of 2–3 μm are released into the air, enter the airway, and reach alveoli [9]. Therefore, the lung is the main organ affected by Aspergillus. Isolation of Aspergillus spp. from lower respiratory tract (LRT) samples (e.g. sputum, bronchial aspirate, or bronchoalveolar lavage) provides important etiologic evidence for its identification. Aspergillus spp. causes various diseases in lungs, such as Aspergillus colonization, Aspergillus infection and allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillus [10]. In COPD patients, impairment of the defense mechanisms of airways facilitates the binding of conidia to epithelial cells, which may cause Aspergillus colonization in the airway [11]. Positive isolation of Aspergillus spp. in LRT samples from COPD patients is common, and a previous study reported that the positive identification rate was nearly 29% [12]. However, clinical manifestations of COPD patients with Aspergillus spp. colonization from LRT have rarely been summarized and are difficult to distinguish, often leading to debate in clinical practice. Consequently, it is difficult for clinicians to make treatment strategies for Aspergillus colonization. The aims of this study were to investigate the clinical features of COPD patients with Aspergillus colonization in LRT, to analyze the risk factors that could predict the possibility of Aspergillus spp. isolation and to summarize the clinical treatment choices and outcomes of COPD patients with Aspergillus colonization.

Methods

Study design

This pair-matched study was conducted from January 2014 to March 2016 in the Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine in Beijing Hospital, China. Patient data were collected from the electronic medical records system of our hospital and by additional chart review. The data used was part of our project “Study on Aspergillus of COPD patients”, which was approved by the ethics committee of Beijing Hospital (Approval notice number 2013BJYYEC-024-01). The informed consent was obtained from all participants in written form.

Mentioned conditions

Conditions | |

|---|---|

A | Age between 18 and 90 years old. |

B | The diagnosis of COPD was based on the Global Initiative for GOLD guidelines. COPD exacerbations are defined as an acute worsening of respiratory symptoms that result in additional therapy. |

C | Positive isolation of Aspergillus spp. in an LRT sample by microbiologic examination. LRT samples included sputum, bronchial aspirate, and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF). |

D | Patients without any chest CT findings of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA), invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA), allergic bronchopulomnary aspergillosis (ABPA), pneumonia. |

Inclusion criteria

Definition | |

|---|---|

Aspergillus colonization | fulfilled above condition C and D above. |

Aspergillus colonization group | fulfilled all conditions above, including A, B, C and D. |

Control group | COPD patients who were admitted a day before or after the Aspergillus colonization group patients were recruited to the control group. At the same time, patients fulfilled above conditions A, B and D. |

Exclusion criteria

-

(1)

Immunocompromised patients, including those with allogeneic or autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, neutropenia, hematologic malignant disease and solid tumor, hematologic stem cell or solid-organ transplantation, and AIDS, as were patients receiving high-dose immunosuppressive agents (e.g. for connective tissue disease and vasculitis).

-

(2)

Patients with chest CT findings of CPA, IPA, ABPA, pneumonia.

-

(3)

Patients with other underlying lung diseases.

Microbiological examination

When patients admitted into hospital, their LRT samples were delivered for microbiological examination the next day. Microbiological examination included direct microscopy and bacterial and fungal pathogen cultvation. All samples were cultured on conventional media, including blood agar, chocolate agar, MacConkey agar and Sabouraud’s dextrose agar. Bacterial infection was defined as a colony count ≥105 cfu/mL. Aspergillus and other fungal isolates were identified using microculture and standard morphological procedures.

Data collection

Following information was collected from the electronic medical records system of our hospital: patient characteristics (sex, age, etc.), lung function, administration of corticosteroids and nutritional status before admission, clinical symptoms and signs, chest imaging and CT scan data, laboratory test results (IgE, eosinophil counts, etc.), microbiologic findings of LRT samples, treatment during hospitalization, remission time (defined as the duration of stabilization of clinical symptoms and disappearance of signs, like the typical symptoms of cough, sputum, wheeze, and the typical signs of wheezing rale), length of hospitalization or ICU stay, and mortality.

Statistical analysis

Normally distributed continuous variables were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation and were compared with a t-test. Non-normally distributed continuous variables were expressed as medians and quartiles and were compared with the Mann-Whitney U-test. Categorical variables were compared with chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Logistic regression was used to identify independent risk factors for Aspergillus colonization. The first logistic regression analysis univariately considered the explanatory variables in stable stage. Only variables with p value < 0.10 in univariate analysis were entered in the multivariate analysis, using a backward stepwise method, with a probability value for the entry of p = 0.10 and removal of p = 0.05. Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the time from admission to remission of symptoms. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 19.0.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Study performance

A total of 504 patients diagnosed with AECOPD were admitted to hospital from January 2014 to March 2016. Aspergillus spp. was identified in the LRT samples of 42 patients (all from qualified sputum specimen), resulting in a detection rate of 8.33%. According to the exclusion criteria, 19 patients with Aspergillus spp. in their sputum samples were excluded from this study, including 9 patients with IPA infection, 5 patients with other pulmonary diseases (asthma: 4 cases, bronchiectasis: 1 case), 2 patients with cancer (lung cancer: 1 case, prostate cancer: 1 case), 1 patient being treated with immunosuppressive agents for connective tissue disease, 1 patient with agranulocytosis and 1 patient who was unable to participate lung function test. Finally, 23 patients with Aspergillus colonization were included in the study group. After performing matching at a ratio of 1:3 (one study group patient to three control group patients), a total of 92 patients were enrolled in this study shown in Fig. 1.

Demographic characteristics and treatment during stable stage

Patients in Aspergillus colonization group consisted of 20 men and 3 women with a median age of 76 ± 7 years. Most of these patients were current smokers with a smoking duration of more than 40 pack-years. All patients were classified by GOLD stage severity. The forced expiratory volume 1 (FEV1) of patients in Aspergillus colonization group was worse according to GOLD severity classification than that of patients in control group (FEV1% predicted: 40.0% ± 16.0% vs 44.5% ± 16.8%). Patients in Aspergillus colonization group also had more underlying diseases, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus and coronary heart disease, than patients in control group. The percentage of inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) use during the stable stage was higher in Aspergillus colonization group than that of control group (73.9% vs 40.6%, p = 0.008). Besides, more patients received a daily dose of beclomethasone greater than 1000 μg (30.4% vs 11.6%, p = 0.048), which was significantly different from patients in control group. The demographic characteristics of patients in Aspergillus colonization and control groups were listed in Table 1.

Univariable baseline analysis showed that smoking history, chronic heart failure and corticosteroids use were risk factors for Aspergillus colonization in COPD patients’ LRT. After multivariable adjustment, only corticosteroids use was independently associated with Aspergillus colonization in COPD patients’ LRT (OR 4.685, 95% CI 1.529–14.355), shown in Table 2.

Clinical manifestations in the exacerbation stage

The clinical characteristics and selected laboratory abnormalities of included patients were shown in Table 3. Most patients exhibited fever, cough, dyspnea and wheezing. Wheezing and wheezing rales were the most specific symptom and sign, which were significantly common in Aspergillus colonization group (wheezing: 52.2% vs 15.9%, p = 0.001; wheezing rales: 65.2% vs 38.2%, p = 0.031). Laboratory results showed that the number and percentage of eosinophils (EOS) were significantly decreased in patients in Aspergillus colonization group compared to those in control group (EOS% > 5%: 4.3% vs 23.2%, p = 0.044). Arterial blood gas was measured in all patients, but no significant differences were observed between two groups. Some inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and total IgE levels, were not significantly different between two groups.

Detection of pathogenic bacteria and other fungi

To investigate whether Aspergillus colonization was associated with combined identification of other specific microbial pathogens, we compared the cultivation results of LRT samples from the Aspergillus colonization group and control group. Particular attention was paid to pathogenic bacteria identification, including Acinetobacter baumannii, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumonia, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia and Enterococcus faecium. The percentage of pathogens identification in two groups showed no statistical difference (Additional file 1: Table S1). Besides, some of other fungi were also detected in our microbiologic cultivation, especially Saccharomycetes.

Patient treatment during hospitalization and short-term outcomes

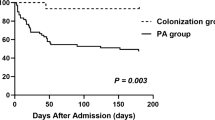

The Aspergillus colonization group included a higher percentage of patients who received more than one class of antibiotics (52.2% vs 20.3%, p = 0.006) and had a longer duration of antibiotic usage (13 ± 5 vs 10 ± 4 days, p = 0.003) than that of the control group. In addition to antibiotic treatment, systemic corticosteroids and/or ICS were used to control wheezing symptom. The percentage of patients in Aspergillus colonization group who use high dose of inhaled corticosteroids (accumulated budesonide dose: no less than 40 mg) were higher than that of control group (30.4% vs 5.8%, p = 0.002). Remission time curve was estimated by Kaplan-Meier analysis. Median remission time was 10 days in the Aspergillus colonization group and 6 days in the control group (log-rank test p = 0.004) (Fig. 2). The duration of hospitalization were longer in the Aspergillus colonization group than it is in the control group (15 ± 5 days vs 12 ± 4 days, p = 0.011), shown in Table 4.

Discussion

AECOPD is often associated with infectious agents, including bacteria, virus and fungi. A previous study was conducted in critically ill patients with isolation of Aspergillus spp. from the respiratory tract, with mortality rates of 50% in the colonization group and 80% in the invasive infection group after 9 months of follow-up [13]. Therefore, clinicians usually focus on infection when a positive Aspergillus spp. culture is obtained from the LRT. However, the significance of a more frequent clinical phenomenon, Aspergillus spp. colonization, has yet to be clarified. In this research, a pair-matched observational study was conducted to investigate the differences in the clinical manifestations and short-term outcomes between COPD patients with and without Aspergillus colonization in LRT.

Cigarette smoking, one of the major risk factors for the development of COPD, induces structural and functional changes in airway epithelium in vitro and in vivo [14,15,16]. In our study, the number of patients with a history of smoking was higher in the Aspergillus colonization group than in the control group, which indicated that smoking is a potential risk for Aspergillus colonization. Cigarette smoking and repeated airway inflammation could alter the structure and function of lung and injure a profound effect on the host defense against invading pathogens and particulates, thus impairing the airway epithelium [17, 18] and mad COPD patients more susceptible to Aspergillus colonization. Meanwhile, most patients in the Aspergillus colonization group received higher doses of ICS during stable stage treatment, in contrast to the control group. Our findings were consistent with a previous study that suggested that high-dose corticosteroids use was a risk for Aspergillus colonization or positive Aspergillus culture [19, 20].

In our study, Aspergillus-colonized patients presented with wheezing and wheezing rales in the acute exacerbation period. More than half of the patients received systemic corticosteroids and/or ICS. The percentage of corticosteroid usage in the two groups was similar, but in the Aspergillus colonization group, patients received higher doses of ICS. This finding suggested that Aspergillus colonization contributed to an increased severity of exacerbations in COPD patients. These phenomena suggested that high-dose ICS treatment was related to Aspergillus colonization and induced similar clinical manifestations to allergic reactions due to Aspergillus colonization. A previous study on the mechanism involved in Aspergillus-related allergic reactions was based on the Aspergillus hyphae and involved antigen-triggered mast cell degranulation and release of histamine and inflammatory factors [21,22,23,24]. These data showed that Aspergillus colonization may aggravate airway hyper-responsiveness and worsen airway inflammation and bronchoconstriction. But no cohort study of patients with repeated cultures of Aspergillus have been done in COPD patients, it is unclear whether fungal colonization contributes to lower lung function or is a marker of more severe lung disease and aggressive therapy. In our study, patients with Aspergillus colonization had a longer time to be stable and a longer duration of hospitalization, which indicated that Aspergillus colonization was related with clinical manifestations and short-term outcomes of COPD patients.

After demonstrating the significance of Aspergillus colonization in the airways of COPD patients, we highlighted an essential clinical treatment dilemma: whether to eliminate colonization with anti-fungal therapy or to stabilize wheezing with continuous ICS. Because Aspergillus colonization is clinically significant, the treatment strategy should aim to eliminate colonization. However, a previous study showed that the removal of Aspergillus colonization did not improve lung function in a long-term observation; this finding cast doubt on the value of anti-fungal therapy. Due to the lack of research on the effect of Aspergillus colonization on AECOPD and stable COPD, challenges remain for clinical decision making. The relationship between colonization and invasive infection is unclear. Whether increasing the fungal load of colonization in the airway could result in invasive pulmonary mycosis has not been determined. Aspergillus colonization induces sustainable inflammation in the airway, which leads to worsening lung function. Meanwhile, poorer lung function is significantly associated with Aspergillus colonization. However, in clinical practice, ICS are commonly used to control wheezing and airway inflammation, which could also enhance the risk of Aspergillus colonization in the airway. It is concerning that once Aspergillus colonization in the airways of COPD patients is identified, a vicious cycle is established. Unfortunately, no accurate timing, biomarker, or scoring system exists that could determine the optimal antifungal therapy.

There were some limitations to this study: (1) we could not determine the timing of Aspergillus colonization: the acute exacerbation or stable stage; (2) we only conducted this retrospective study without a long-term observation from the beginning of Aspergillus colonization to its causing symptomatic clinical manifestation. Thus, whether Aspergillus colonization could affect the clinical process was still unknown, including lung function decline, the frequency of acute exacerbation, and daily symptoms; and (3) we performed this research in a single center and recruited a small sample of patients.

Conclusions

Our findings show that Aspergillus colonization in the airway could cause significant change in clinical manifestations and treatment outcome of COPD patients. This study provides new insight for clinicians when managing patients with fungal colonization and also indicates the directions for future comprehensive studies, including the development of a reliable and rapid method to accurately identify infection and colonization and to develop a full-scale investigation and treatment strategy of COPD patients with Aspergillus colonization.

Abbreviations

- ABPA:

-

Allergic bronchopulomnary aspergillosis

- AECOPD:

-

Acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- BALF:

-

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CPA:

-

Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- EOS:

-

Eosinophils

- ESR:

-

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- FEV1 :

-

Forced expiratory volume 1

- GOLD:

-

Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease

- ICS:

-

Inhaled corticosteroids

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IPA:

-

Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis

- LRT:

-

Lower respiratory tract

References

WHO. The top 10 causes of death. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs310/en/. Date last updated: 27 Oct 2016.

WHO. Burden of COPD. http://www.who.int/respiratory/copd/burden/en/. Date last updated: 15 Mar 2017.

Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3(11):e442.

Banerjee D, Khair OA, Honeybourne D. Impact of sputum bacteria on airway inflammation and health status in clinical stable COPD. Eur Respir J. 2004;23(5):685–91.

Patel IS, Seemungal TAR, Wilks M, Lloyd-Owen SJ, Donaldson GC, Wedzicha JA. Relationship between bacterial colonisation and the frequency, character, and severity of COPD exacerbations. Thorax. 2002;57(9):759–64.

Wedzicha JA, Donaldson GC. Exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Care. 2003;48(12):1204–13.

Streifel AJ, Lauer JL, Vesley D, Juni B, Rhame FS. Aspergillus fumigatus and other thermotolerant fungi generated by hospital building demolition. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983;46(2):375–8.

Latgé JP. The pathobiology of aspergillus fumigatus. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9(8):382–9.

Bulpa P, Dive A, Sibille Y. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2007;30(4):782–800.

Soubani AO, Chandrasekar PH. The clinical spectrum of pulmonary aspergillosis. Chest. 2002;121(6):1988–99.

Latgé JP. Aspergillus fumigatus and aspergillosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12(2):310–50.

Pashley CH, Fairs A, Morley JP, et al. Routine processing procedures for isolating filamentous fungi from respiratory sputum samples may underestimate fungal prevalence. Med Mycol. 2012;50(4):433–8.

Garnacho-Montero J, Amaya-Villar R, Ortiz-Leyba C, et al. Isolation of Aspergillus spp. from the respiratory tract in critically ill patients: risk factors, clinical presentation and outcome. Crit Care. 2005;9(3):R191–9.

Kohansal R, Martinez-Camblor P, Agustí A, Buist AS, Mannino DM, Soriano JB. The natural history of chronic airflow obstruction revisited: an analysis of the Framingham offspring cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(1):3–10.

Nyunoya T, Mebratu Y, Contreras A, Delgado M, Chand HS, Tesfaigzi Y. Molecular processes that drive cigarette smoke-induced epithelial cell fate of the lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2014;50(3):471–82.

Amitani R, Murayama T, Nawada R, et al. Aspergillus culture filtrates and sputum sols from patients with pulmonary aspergillosis cause damage to human respiratory ciliated epithelium in vitro. Eur Respir J. 1995;8(10):1681–7.

Jones JG, Minty BD, Lawler P, Hulands G, Crawley JC, Veall N. Increased alveolar epithelial permeability in cigarette smokers. Lancet. 1980;1(8159):66–8.

Hulbert WC, Walker DC, Jackson A, Hogg JC. Airway permeability to horseradish peroxidase in guinea pigs: the repair phase after injury by cigarette smoke. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1981;123(3):320–6.

Muquim A, Dial S, Menzies D. Invasive aspergillosis in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases. Can Respir J. 2005;12(4):199–204.

Bafadhel M, McKenna S, Agbetile J, et al. Aspergillus fumigatus during stable state and exacerbations of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(1):64–71.

Urb M, Snarr BD, Wojewodka G, et al. Evolution of the immune response to chronic airway colonization with Aspergillus fumigatus hyphae. Infect Immun. 2015;83(9):3590–600.

Saluja R, Metz M, Maurer M. Role and relevance of mast cells in fungal infections. Front Immunol. 2012;3:146.

Urb M, Pouliot P, Gravelat FN, Olivier M, Sheppard DC. Aspergillus fumigatus induces immunoglobulin E-independent mast cell degranulation. J Infect Dis. 2009;200(3):464–72.

Chaudhary N, Marr KA. Impact of Aspergillus fumigatus in allergic airway diseases. Clin Transl Allergy. 2011;1(1):4.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Academician Chen Wang for his guidance and assistance with this work. We acknowledge the China National Center for Protein Sciences Beijing for providing facility support.

Funding

This project was supported by project grant 2012AA02A511 from the National High Technology Research and Development Program, China; grant 2012BAI05B02 from the National Key Technology Research and Development Program, China; grant 81400037 from the National Natural Science Foundation of China; and grant 201302017 from the Public Health Special Research of the Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Beijing Hospital Clinical Database Centre, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Beijing Hospital Clinical Database Centre.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YL and XT contributed to the conception and design of the study, acquisition of the data, and interpretation of the results and drafted the manuscript. AC contributed to the acquisition of the mycological data and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. HX contributed to the acquisition of the bacteriological data and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. SZ performed the statistical analysis and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The data used in this study was part of our project “Study on Aspergillus of COPD patients”, which was approved by the ethics committee of Beijing Hospital (Approval notice number 2013BJYYEC-024-01). The informed consent to participate was obtained from all participants in written form.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Detection of pathogenic bacteria and other fungi. (DOCX 14 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Tong, X., Cheng, A., Xu, H. et al. Aspergillus fumigatus during COPD exacerbation: a pair-matched retrospective study. BMC Pulm Med 18, 55 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-018-0611-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-018-0611-y