Abstract

Background

During an evolving influenza pandemic, community mitigation strategies, such as social distancing, can slow down virus transmission in schools and surrounding communities. To date, research on school practices to promote social distancing in primary and secondary schools has focused on prolonged school closure, with little attention paid to the identification and feasibility of other more sustainable interventions. To develop a list and typology of school practices that have been proposed and/or implemented in an influenza pandemic and to uncover any barriers identified, lessons learned from their use, and documented impacts.

Methods

We conducted a review of the peer-reviewed and grey literature on social distancing interventions in schools other than school closure. We also collected state government guidance documents directed to local education agencies or schools to assess state policies regarding social distancing. We collected standardized information from each document using an abstraction form and generated descriptive statistics on common plan elements.

Results

The document review revealed limited literature on school practices to promote social distancing, as well as limited incorporation of school practices to promote social distancing into state government guidance documents. Among the 38 states that had guidance documents that met inclusion criteria, fewer than half (42%) mentioned a single school practice to promote social distancing, and none provided any substantive detail about the policies or practices needed to enact them. The most frequently identified school practices were cancelling or postponing after-school activities, canceling classes or activities with a high rate of mixing/contact that occur within the school day, and reducing mixing during transport.

Conclusion

Little information is available to schools to develop policies and procedures on social distancing. Additional research and guidance are needed to assess the feasibility and effectiveness of school practices to promote social distancing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

During communicable disease outbreaks such as pandemic influenza, social distancing interventions that increase the space between people and decrease the frequency of contacts can play an important role in emergency response [1, 2]. Influenza pandemics typically have multiple waves and can last for months [3, 4]. The most recent pandemic in the United States was the 2009–2010 H1N1influenza pandemic, which disproportionately impacted children and young adults [5, 6].

During an evolving influenza pandemic, community mitigation strategies, such as social distancing, can slow down virus transmission in schools and surrounding communities, helping to relieve pressure on over-burdened healthcare and public health systems and buy time for pandemic vaccine production and distribution [7]. Because schools are socially dense environments where students congregate for many hours of the day, schools can fuel community-wide disease transmission [8, 9]. It follows that school practices that promote social distancing could potentially protect large numbers of vulnerable children, as well as limit secondary transmission to adults within their households and communities.

Despite the potential impact of school practices on disease transmission, research on school practices to promote social distancing in primary and secondary schools has focused on prolonged school closure [10,11,12], with little attention paid to the identification and feasibility of other more sustainable interventions that are less costly for society. Although many states and grant programs require school districts and individual schools to plan for infectious disease outbreaks, such as pandemic influenza, there is a paucity of published research on the content of these planning documents. Thus, pandemic influenza guidance documents and plans produced by state governments are a potential source of information on school practices to promote social distancing, as well as practical and policy barriers to the adoption of those practices.

To fully characterize and identify gaps in the literature on school practices to promote social distancing in a communicable disease outbreak, we reviewed both peer-reviewed and grey literature on social distancing interventions in schools other than school closure. We also collected and catalogued state government planning documents to assess state policies regarding social distancing interventions. Our aims were to develop a list and typology of school practices that have been proposed and/or implemented, summarize any barriers identified and lessons learned from their use, and summarize documented impacts. Such a typology can be of use to state and local education agencies as they consider their options for emergency planning.

Methods

Literature review

From September–October 2016, the lead author and research assistant independently conducted searches of 10 education, public health, and general library catalogue databases. Multiple databases (e.g., EBSCO Information Services, WorldCat, New York Academy of Medicine) cover both peer-reviewed and grey literature sources, including reports, newspaper, newsletter, and magazine articles. We restricted our search to articles published after 2000.

Within each database, either the lead author or research assistant first conducted a broad search using the search terms “school and (pandemic or influenza).” In instances where that search strategy yielded fewer than 1000 results, we reviewed all abstracts and did not run additional searches. In contrast, when more than 1000 results were returned, we conducted two additional, narrower searches. We first re-ran “school and (pandemic or influenza),” and required that these terms appear in the title and/or abstract. We then also ran the search terms “school AND (influenza or pandemic) AND (social distancing or practices or strategies or measures or interventions).” Table 1 shows the databases searched, final search terms, and results.

Both the lead author and research assistant reviewed the same set of approximately 2000 unique abstracts that were identified through these database searches, as well as the reference lists of relevant articles, selecting 46 articles for full text review. Abstracts were excluded if they were: (1) not related to K-12 school practices or policies to promote social distancing in an infectious disease outbreak; (2) focused on schools other than K-12 (e.g., university planning for pandemic influenza); (3) published in a language other than English; or (4) only focused on sustained school closure rather than other potential school practices. The majority of abstracts were excluded because they were not related to K-12 school practices or policies to promote social distancing in an infectious disease outbreak (e.g., abstract focused on routine hygiene practices in schools).

Of the 46 articles that were selected for full text review, 30 did not mention a single (non-school closure) strategy, leaving 16 for our review.

To obtain relevant information from each reviewed article in a standardized manner, we developed an abstraction form. The form included the following items: article abstract, study design, study location/population, school practices identified, barriers to implementation, impact of school practices, and notes/observation. A researcher or research assistant collected data on each article using that form.

State government planning document review

We first conducted Google searches to identify state-level documents from 50 states and the District of Columbia to support public school planning. We sought to identify one document per state that provided guidance to its local education agencies (LEA) or schools. We excluded general pandemic influenza preparedness plans that were not directed to local education agencies or schools. To locate these documents, we conducted online searches that had various combinations of the following terms: [name of state], school, education, pandemic influenza, infectious disease, communicable disease, emergency response, guidance, and plan. Our goal was to identify pandemic-specific documents, either stand-alone documents or chapters or annexes in a larger emergency plan. However, when we could not identify a document specific to pandemic influenza, we then searched for materials related to infectious disease or emergency planning more broadly. In instances where we identified more than one guidance document within a state that met inclusion criteria, we selected the document that was published most recently.

Each plan/planning document was reviewed by a researcher or research assistant, and the following information was extracted: state name, type of plan (pandemic, infectious disease, emergency plan), author of plan, year plan was written, whether hygiene practices were discussed, whether school closure was discussed, whether distance learning was discussed, whether school practices to promote social distancing were discussed (and if yes, what types), and any included details about barriers, facilitators, or considerations for social distancing. RAND’s Institutional Review Board approved this study, determining that it did not involve human subjects and informed consent did not apply.

Results

Literature review

Of the 16 articles that met all inclusion criteria, 6 (38%) presented the results of agent-based simulation studies/modeling, and 5 (31%) presented the results of surveys regarding school practices during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. The other five articles were a combination of commentaries, magazine or newsletter articles, and miscellaneous research articles.

Included articles identified more than a dozen different types of school practices to promote social distancing, many of which were slight variations on one another. Table 2 shows these practices as they were initially presented.

For ease of interpretation, we created categories of practices and calculated how often they were mentioned across articles (Table 3). The practices identified most frequently included canceling or postponing after-school activities (n = 6, 38%), increasing space among students during in-person instruction (n = 5, 31%), and canceling classes or activities with a high rate of mixing/contact that occur within the school day (n = 5, 31%). While canceling or postponing activities was mentioned frequently, it is unclear whether the intent of this practice, as implemented during the 2009–2010 H1N1 pandemic, was to reduce contact among students or a logical response to high rates of absenteeism or community concern.

Distance learning was mentioned in 2 (13%) articles [13, 14]. Ash et al. explained that distance learning is supported by various technologies such as the Internet, telephone, radio, TV, text messaging via cellphones, e-mail, and podcasts [14]. Furthermore, during the H1N1 pandemic, there were examples of lessons being broadcast on public access television and studies using text messaging for study groups. However, because distance learning is used in combination with other practices such as school closure, partial school closure, or reduced schedule to achieve the social distancing of students enrolled in traditional bricks and mortar K-12 public schools, we do not list distance learning practices in Table 3.

Surveys of school responses to the H1N1 pandemic provided some data on how often schools implemented different practices. No single social distancing practice, aside from school closure, was widely used. The two most common practices were rearranging classrooms to increase the physical distance between students (implemented in 14% of schools across the state of Michigan in one study) and canceling or postponing various school activities (implemented by 5–16% of schools in one study, depending on the activity) [15]. No other practice was implemented by more than 10% of surveyed schools in any given study [16,17,18,19]. There were, however, widespread practices to limit disease spread that were not forms of social distancing. For example, schools routinely isolated ill students and promoted hand hygiene and respiratory etiquette during the H1N1 pandemic.

Very few of the articles (n = 2) we reviewed discussed barriers to implementing school practices to support social distancing. Ridenhour et al... mentioned the challenge of enforcing restrictions on the movement of students within a school (e.g., hall restriction, lunchroom restriction) [20], while Ash et al touched on the challenges of implementing distance learning in instances where students do not have access to broadband Internet or required hardware, such as laptops [14]. Additionally, young children and their families may not have the necessary technical skills to participate in online instruction, as opposed to the traditional delivery of instruction that occurs in-person.

All of the studies that used agent-based simulation models, and one epidemiologic study, reported that at least one school practice to promote social distancing could reduce contact among students and/or disease transmission (Table 4). Because articles focused on different practices, with the exception of class or grade closure, it is difficult to draw any conclusions about the likely effectiveness of different practices at this phase of research.

State government planning document review

In our review of planning documents, we found that 38 of 51 (75%) states had published guidance for local education agencies or schools to support planning for pandemic influenza or communicable disease outbreaks in schools (Table 5). Among the guidance documents we identified, 42% (16 of 38) mentioned one or more school practices to promote social distancing. By contrast, almost all guidance documents (n = 36, 95%) discussed hand hygiene and/or sanitation, a large majority (n = 34, 89%) discussed school closure, and a little less than half (n = 16, 42%) discussed distance learning. As noted in Table 5, the plans and guidance were developed from 2002 to 2016. However, 23 (61%) were published on or after 2009, with 7 (18%) in 2009 alone. Pandemic planning was likely accelerated by the H1N1 pandemic that occurred from 2009 to 2010.

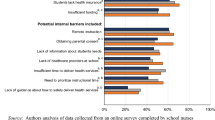

Among the 16 guidance documents that mentioned social distancing, the practices identified most frequently included canceling or postponing after-school activities (n = 11, 69%), canceling classes or activities with a high rate of mixing/contact that occur within the school day (n = 7, 44%), and reducing mixing during transport (n = 6, 38%) (Table 6). State-level guidance documents discussed all of the practices identified in the literature and also identified two unique practices not covered elsewhere: instituting homeroom stay (in which students remain in one classroom and teachers rotate in and out) (n = 1, 6%) and limiting visitors (n = 1, 6%).

In general, state government guidance documents devoted very little space to school practices to promote social distancing and typically included practices among lists of potential response options, without any details regarding barriers, facilitators, or considerations. Only one document discussed barriers or considerations regarding the implementation of school practices to promote social distancing. Connecticut’s guidance document mentioned that any practice that reduces the number of instructional hours will require waivers of instruction requirements.

Discussion

Our review revealed a very limited literature on school practices to promote social distancing other than school closure and limited incorporation of school practices to promote social distancing into state-level guidance documents. Fewer than half of all states with guidance documents mentioned a single school practice to promote social distancing, and none provided any substantive detail about the policies or practices needed to enact the listed school practice. This lack of detail is not surprising, given that school practices to promote social distancing have not been prominently featured in previous federal guidance to schools, and many state governments use federal guidance to inform their planning efforts [21].

Although we hypothesized that the evidence would be scant, we were surprised to see how few school practices were identified or described. For example, although the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) mentions homeroom stay in some of its guidance materials [22], none of the articles, and only two state-level guidance documents we reviewed, mentioned this practice.

Our review of guidance documents identified certain practices that do not appear in the peer-reviewed and grey literature. For example, homeroom stay and visitor restrictions were mentioned in guidance, but did not appear in our peer-reviewed and grey literature review. Furthermore, guidance documents more frequently discussed reducing mixing during transport to and from school.

According to survey data, schools focused their efforts on hand hygiene, respiratory etiquette, and cleaning/disinfecting school buildings, but seldom implemented practices to promote social distancing as a response to the H1N1 pandemic. Nevertheless, published studies that used simulation modeling generally found that practices to promote social distancing could be effective (and less disruptive to society compared to school closure) in curbing disease transmission. However, it is unclear whether these theoretical benefits would be realized following implementation in real-world settings. At the present time, there are only a handful of studies that explore a variety of different practices under a range of different assumptions. As such, it is premature to draw any conclusions about the likely impact of these practices in schools during pandemics.

In the literature and documents we reviewed, school practices were not clearly defined and terms were used inconsistently. This was especially true for school closure. In certain cases, authors used this term to refer to sustained closures (which is out of scope for this review) of weeks or months; however, a one-day “snow day” or class or grade closure were also referred to as “school closure” in select circumstances. To address this issue, we developed a classification system for practices other than sustained school closure and included concrete examples of practices within each defined category. This system, fully characterized in Table 5, can be used going forward to: (1) provide a menu of options to schools selecting among social distancing measures and (2) ensure that educators and policy-makers are speaking a common language regarding school practices to promote social distancing.

Our study has several limitations. First, as described above, terms related to school practices are used inconsistently in the literature and, as such, our search strategy may have inadvertently excluded relevant articles (e.g., articles that refer to school dismissal or school closure but actually cover scenarios of partial closure). Second, we only reviewed publicly available guidance documents targeting local education agencies and/or schools that were posted on the Internet. It is possible that certain states have relevant guidance documents that are not posted and, as such, were not included in this review. It is also possible that, in general, pandemic influenza plans and guidance documents (excluded in this review) could have content relevant to school practices to promote social distancing. To test this possibility, we reviewed eight general pandemic influenza plans from states without school-specific guidance and did not find examples of school social distancing practices other than school closure [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. Despite certain limitations, this is the first review of school practices, other than sustained school closure, and state government guidance on pandemic influenza that we are aware of.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that little information is available to schools to develop policies and procedures on social distancing. School leaders and decision-makers can use the findings presented here to understand the range of potential school practices available to them and the evidence supporting their use. Additional research and guidance is needed to assess the feasibility and effectiveness of school practices to promote social distancing to inform federal, state, and local planning efforts going forward.

Abbreviations

- CDC:

-

Centers for disease control and prevention

- K-12:

-

Kindergarten through Grade 12

- LEA:

-

Local education agency

References

Qualls N, Levitt A, Kanade N, et al. Community mitigation guidelines to prevent pandemic influenza - United States, 2017. MMWR Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report Recommendations and reports. 2017;66(1):1–34.

Earn DJ, He D, Loeb MB, Fonseca K, Lee BE, Dushoff J. Effects of school closure on incidence of pandemic influenza in Alberta, Canada. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(3):173–81.

Bootsma MC, Ferguson NM. The effect of public health measures on the 1918 influenza pandemic in U.S. cities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(18):7588–93.

He D, Dushoff J, Eftimie R, Earn DJ. Patterns of spread of influenza a in Canada. Proceedings Biological sciences. 2013;280(1770):20131174.

Glatman-Freedman A, Portelli I, Jacobs SK, et al. Attack rates assessment of the 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza a in children and their contacts: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e50228.

Cox CM, Blanton L, Dhara R, Brammer L, Finelli L. 2009 pandemic influenza a (H1N1) deaths among children--United States, 2009-2010. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(Suppl 1):S69–74.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2017 community strategy for pandemic influenza mitigation in the United States: pre-pandemic planning guidelines for the use of nonpharmaceutical interventions. MMWR. 2017.

Chao DL, Halloran ME, Longini IM Jr. School opening dates predict pandemic influenza a(H1N1) outbreaks in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2010;202(6):877–80.

Gog JR, Ballesteros S, Viboud C, et al. Spatial transmission of 2009 pandemic influenza in the US. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10(6):e1003635.

Jackson C, Mangtani P, Hawker J, Olowokure B, Vynnycky E. The effects of school closures on influenza outbreaks and pandemics: systematic review of simulation studies. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e97297.

Jackson C, Vynnycky E, Hawker J, Olowokure B, Mangtani P. School closures and influenza: systematic review of epidemiological studies. BMJ Open. 2013;3(2)

Rashid H, Ridda I, King C, et al. Evidence compendium and advice on social distancing and other related measures for response to an influenza pandemic. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2015;16(2):119–26.

McGiboney G, Fretwell Q. Pandemic Planning for Schools. In. American School Board Journal. Jun2007, Vol 194 Issue 6, p46–47. 2p. 1 Color Photograph.. Vol 1942007:46–47.

Ash K. E-Learning's Potential Scrutinized In Flu Crisis. In: Education Week, vol. 282009. p. 1–13.

Shi J, Njai R, Wells E, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of nonpharmaceutical interventions following school dismissals during the 2009 influenza a H1N1 pandemic in Michigan, United States. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e94290.

Miller JR, Short VL, Wu HM, et al. Use of nonpharmaceutical interventions to reduce transmission of 2009 pandemic influenza a (pH1N1) in Pennsylvania public schools. J. Sch. Health. 2013;83(4):281–9.

Nasrullah M, Breiding MJ, Smith W, et al. Response to 2009 pandemic influenza a H1N1 among public schools of Georgia, United States--fall 2009. International journal of infectious diseases : IJID : official publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases. 2012;16(5):e382–90.

Rebmann T, Elliott MB, Swick Z, Reddick D. US school morbidity and mortality, mandatory vaccination, institution closure, and interventions implemented during the 2009 influenza a H1N1 pandemic. Biosecurity and bioterrorism : biodefense strategy, practice, and science. 2013;11(1):41–8.

Dooyema CA, Copeland D, Sinclair JR, et al. Factors influencing school closure and dismissal decisions: influenza a (H1N1), Michigan 2009. J. Sch. Health. 2014;84(1):56–62.

Ridenhour BJ, Braun A, Teyrasse T, Goldsman D. Controlling the spread of disease in schools. PLoS One. 2011;6(12):e29640.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim Pre-pandemic Planning Guidance: Community Strategy for Pandemic Influenza Mitigation in the United States. 2007; https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/11425.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC guidance for state and local public health officials and school administrators for school (K-12) responses to influenza during the 2009–2010 school year. 2010; http://www.cdc.gov/h1n1flu/schools/schoolguidance.htm. Accessed 7-20-16.

Kansas Department of Health and Environment. Kansas Pandemic Influenza Preparedness and Response Plan. 2016; http://www.kdheks.gov/cphp/download/KS_PF_Plan.pdf. Accessed 3-20-17.

State of Maine Department of Health and Human Services. Pandemic Influenza Operations Plan. 2013; http://www.maine.gov/dhhs/mecdc/infectious-disease/epi/influenza/maineflu/documents/piop/BasePlanv1-4F8-21-13.pdf. Accessed 3-20-17.

Nevada State Health Division Department of Health and Human Services. PANDEMIC INFLUENZA PREPAREDNESS AND RESPONSE PLAN. 2007; https://publicintelligence.net/nevada-pandemic-influeza-preparedness-and-response-plan/. Accessed 3-20-17.

North Dakota Department of Health. North Dakota Pandemic Influenza Preparedness and Response Plan. 2010; https://www.health.nd.gov/media/1026/_nd-pandemic-influenza-plan-annex-to-the-state-public-health-plan.doc. Accessed 3-20-17.

Rhode Island Department of Health. Pandemic Influenza Plan. 2006; http://www.library.state.ri.us/publications/DOH/flu/pandemicfluplan.pdf. Accessed 3-20-17.

South Carolina Emergency Management Division. South Carolina Emergency Operations Plan: Pandemic Influenza Annex. 2014; http://www.scemd.org/files/Plans/Mass_Casualty/State_Pandemic_Influenza_Plan_-_July_2014.pdf.

State of Wyoming Department of Health. Public Health Pandemic Influenza Response Plan. 2013; https://health.wyo.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/22-17256_WDHPandemicInfluenzaPlan8.pdf. Accessed 3-20-17.

Hawaii Department of Health. PANDEMIC INFLUENZA PREPAREDNESS & RESPONSE PLAN. 2008; http://helsenet.info/pdf/Influenza/28.pdf, 3–20-17.

Adalja AA, Crooke PS, Hotchkiss JR. Influenza transmission in preschools: modulation by contact landscapes and interventions. Mathematical modelling of natural phenomena. 2010;5(3):3–14.

Fumanelli L, Ajelli M, Merler S, Ferguson NM, Cauchemez S. Model-based comprehensive analysis of school closure policies for mitigating influenza epidemics and pandemics. PLoS Comput Biol. 2016;12(1):e1004681.

Gemmetto V, Barrat A, Cattuto C. Mitigation of infectious disease at school: targeted class closure vs school closure. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:695.

Lofgren E, Rogers J, Senese M. Pandemic preparedness strategies for school systems: is closure really the only way? Ann Zool Fenn. 2008;45(5):449–58.

Cooley P, Bartsch S, Brown S, Wheaton W, Wagener D, Lee B. Weekends as social distancing and their effect on the spread of influenza. Computational and Mathematical Organization Theory. 2016;22(1)

Guidance for K-12 Administrators' Responses to Influenza. In: Education Digest, vol. 752009. p. 8–12.

Stehle J, Voirin N, Barrat A, et al. High-resolution measurements of face-to-face contact patterns in a primary school. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e23176.

Sugisaki K, Seki N, Tanabe N, et al. Effective school actions for mitigating seasonal influenza outbreaks in Niigata, Japan. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e74716.

Alabama State Department of Education. Guidance for Local Education Agency Pandemic Preparedness Response (Suggested). 2014; 18. Available at: https://www.alsde.edu/sec/pss/Communicable/Pandemic_Flu_Preparation.pdf#search=influenza. Accessed 3-1-17.

State of Alaska Division of Public Health. Infectious Disease Management: Guidelines for Alaska Schools. 2013; 179. Available at: http://dhss.alaska.gov/dph/wcfh/Documents/school/assets/InfectiousDiseaseManagementGuidelinesForAlaskaSchools.pdf. Accessed 3–1-17.

State of Arizona Department of Education. Guidance to Schools on Pandemic Preparedness. 2009; 10. Available at: https://www.azed.gov/wp-content/uploads/PDF/Pandemic_Guidance.pdf. Accessed 3-1-17.

Arkansas Department of Health. Arkansas Influenza Pandemic Response Plan. 2014; 154. Available at: http://www.healthy.arkansas.gov/programsServices/preparedness/Documents/CountyPlanningGuidance.pdf, 3–1-17.

California Department of Education. Pandemic Flu Checklist for Local Educational Agencies in California 2014. Accessed 3–1-17.

Colorado Department of Public health and Environment. Pandemic Influenza Action Plan for Schools. 2009; 7. Available at: https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/sites/default/files/OEPR_Pandemic-Influenza-Action-Plan-for-Schools.pdf. Accessed 3-1-17.

Connecticut State Department of Education. Clinical Procedure Guidelines for Connecticut School Nurses. 2012; 124. Available at: http://www.sde.ct.gov/sde/lib/sde/pdf/publications/clinical_guidelines/clinical_guidelines.pdf.

District of Columbia. Introduction School Emergency Response Plan and Management Guide. 2010; 562. Available at: http://esa.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/esa/publication/attachments/school_emergency_response_plan-1-5-10.pdf. Accessed 3–1-17.

Delaware Department of Education. Emergency Preparedness Guidelines and Checklist For Emergency Prepardness Coordinators in Local Educational Agencies. 11. Available at: http://www.doe.k12.de.us/cms/lib09/DE01922744/Centricity/Domain/156/EmerPrepGuideCheck.pdf. Accessed 3-1-17.

Richard Woods. Pandemic Influenza Planning: Information for Georgia Public School Districts. 89. Available at: https://www.gadoe.org/Curriculum-Instruction-and-Assessment/Curriculum-and-Instruction/Documents/Georgia%20DOE%20Information%20for%20Pandemic%20Planning%20October%202015.pdf. Accessed 3–1-17.

Idaho Department of Health and Welfare. IDAHO PANDEMIC INFLUENZA RESPONSE. 2006; https://adacounty.id.gov/Portals/Accem/Doc/PDF/idpandemicfluplan.pdf. Accessed 3-11-17.

Illinois So. School Guidance During an nfluenza Pandemic. 2006; 59. Available at: http://www.idph.state.il.us/pandemic_flu/school_guide/school_pan_flu_guide.pdf. Accessed 3–1-17.

Adams JM, Duwve J, Pontones P. Communicable Disease Reference Guide for Scools, vol. 2015. 2015th ed. p. 126. Available at: http://www.in.gov/isdh/files/Communicable_Disease_Reference_Guide_for_Schools_2015_Edition_Final_July28_2015docx%2D-ppedits.pdf

Iowa Department of Public Health. Guidelines for the Management of Chronic Conditions in Iowa Schools 2012; 21. Available at: https://www.educateiowa.gov/sites/files/ed/documents/1314_sn_GuideforMgmntofChronic.pdf. Accessed 3-1-17.

State of Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals. Pandemic Influenza Guidance Annex 8: Containment and Mitigation. 2011; 38. Available at: http://new.dhh.louisiana.gov/assets/oph/Center-CP/emergprep/ContainmentMitigation_PandemicInfluenzaGuidance_Annex8_April2011.pdf. Accessed 3-1-17.

Maryland State Department of Education. Management of Communicable Diseases In a School Setting. 2002; 13. Available at: http://archives.marylandpublicschools.org/NR/rdonlyres/6561B955-9B4A-4924-90AE-F95662804D90/3284/CommunicableDiseaseFINAL.pdf. Accessed 3-1-17.

Oakland Country Michigan Health Division. Pandemic Planning Workbook: With Supporting Resources. 2006; 86. Available at: http://mdch.train.org/panflu/education/Pandemic%20Workbook_PDF2.pdf. Accessed 3–1-17.

State of Mississippii. Mississippi Pandemic Influenza Incident Annex 2013; 427. Available at: http://msdh.ms.gov/msdhsite/_static/resources/2944.pdf. Accessed 3–1-17.

Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services. Prevention and Control of Communicable Diseases. 247. Available at: http://health.mo.gov/safety/childcare/pdf/PreventionandControlofCommunicableDiseases.pdf. Accessed 3-1-17.

Montana Office of Public Instruction. Pandemic Flu: School Preparation Guide. 2007; http://opi.mt.gov/pdf/health/PandemicFlu.pdf. Accessed 3-1-17.

Services NDoHaH. Nebraska Emergency Guidelines for Schools. 2012; 71. Available at: http://dhhs.ne.gov/publichealth/Documents/NE%20Emergency%20Guidelines%20for%20Schools.pdf. Accessed 3–1-17.

New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services. NH Pandemic Influenza Communication and Coordination Plan for Educational and Child Care Settings. 2008; 10. Available at: http://education.nh.gov/instruction/school_health/documents/pandemic.pdf. Accessed 3-1-17.

New Jersey Department of Health. NJDOH Pandemic Influenza Plan. 2015; 257. Available at: http://www.nj.gov/health/er/documents/pandemic_influenza_plan.pdf. Accessed 3-1-17.

New Mexico Public Education Department. Preparing for Pandemic Flu in New Mexico Schools: Information for Educators and Community Members. 2007; http://www.ped.state.nm.us/schoolfamilysupport/dl/Preparing%20for%20Flu%20in%20NM%20Schools.pdf. Accessed 3-1-17.

New York Sate Department of Health. Pandemic Flu Action Kit. 2007; 67. Available at: https://www.health.ny.gov/diseases/communicable/influenza/pandemic/docs/pandemic_influenza_school_toolkit.pdf. Accessed 3-1-17.

North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. North Carolina's Operational Plan for Pandemic Influenza Preparedness. http://www.nchealthyschools.org/docs/healthissues/pandemicflu/ncpandemicplan.pdf. Accessed 3-1-17.

Ohio Department of Education. School Closure Guidance. 2009; 29. Available at: https://www.odh.ohio.gov/-/media/ODH/ASSETS/Files/chss/school-nursing/influenzaschoolguidance.pdf?la=en. Accessed 3-1-17.

Oklahoma State Department of Health. Oklahoma Emergency Gudelines For Schools. 95. Available at: https://www.ok.gov/health2/documents/New%20Emergency%20Guidelines%20for%20Schools.pdf. Accessed 3-1-17.

State of Oregon. Pandemic Influenza: Emergency Management Plan. 2008; 256. Available at: https://public.health.oregon.gov/DiseasesConditions/CommunicableDisease/DiseaseSurveillanceData/Influenza/Documents/panfluplan.pdf. Accessed 3–1-17.

Pennsylvania Department of Health. Pennsylvania Departmebt of Health: Guidance for School (K-12) Responses to Influenzaa During the 2009–2010 School Year. 2009; 8. Available at: http://www.health.state.pa.us/pdf/flusurvey/padoh_guidance_for_schools_h1n1_2009-2010_final.pdf. Accessed 3-1-17.

Tennessee Office of School Safety and Learning Support. Pandemic Influenza Preparedness: A Planning guide for Tennessee School Districts. 2009; 92. Available at: http://tennessee.gov/assets/entities/education/attachments/csh_pandemic_flu_prep.pdf. Accessed 3-1-17.

Texas Association of School Boards. Responding to the Risk of Infectious Disease in Public Schools. 2014; 21. Available at: https://www.nsba.org/sites/default/files/reports/TASB_Infectious_Disease_Q%26Q_Oct14.pdf. Accessed 3-1-17.

Utah Department of Health. School Pandemic Influenza Preparedness Guidelines. 2006; http://pandemicflu.utah.gov/docs/Utah%20School%20Pandemic%20Influenza%20Guidelines.pdf. Accessed 3-1-17.

Vermont Agency of Human Services. Pandemic Influenza School Action Guidance. 2008; http://healthvermont.gov/panflu/documents/schoolactionguide_sec3.pdf. Accessed 2-10-17.

Virginia Department of Education. Pandemic Influenza Plan: Guidelines for Virgina Public Schools. 2008; 50. Available at: http://www.doe.virginia.gov/support/health_medical/influenza/pandemic_flu_plan_guidelines.pdf. Accessed 3-1-17.

Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction. Infectious Disease Control Guide for School Staff. 2014; 236. Available at: http://www.k12.wa.us/HealthServices/pubdocs/InfectiousDiseaseControlGuide.pdf. Accessed 3-1-17.

West Virginia Department of Education. WVDE Pandemic Influenza Plan. Accessed 3-1-17.

Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction. School District Influenza Plan. 2009; Accessed 3-1-17.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (HHSD2002013M53959B Task Order #200–2016-F-92345). The funder collaborated on all aspects of the research and manuscript preparation.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article, including links in the reference list.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this study are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LUP helped to design the study and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. FA, YZ, AU, and HS helped to design the study and supported interpretation of results. EM and GB supported data collection and analysis and wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

RAND’s Institutional Review Board determined that this study did not involve human subjects.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Uscher-Pines, L., Schwartz, H.L., Ahmed, F. et al. School practices to promote social distancing in K-12 schools: review of influenza pandemic policies and practices. BMC Public Health 18, 406 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5302-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5302-3