Abstract

Background

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have achieved unprecedented success in cancer treatment over the past decade. The application of ICIs hasled to the discovery of various types of immune-related adverse events (irAEs). Here, we report a case of fatal myositis and spontaneous haematoma following concurrent treatment of nivolumab and ipilimumab for pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Case presentation

A 71-year-old gentleman with pancreatic adenocarcinoma underwent the Whipple procedure in September 2014. The patient received 8 cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabineand achieved a complete responsein April 2015. Treatment with the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab was started due to suspected tumour recurrence in November 2015. In August 2016, the CTLA-4 inhibitor ipilimumab was added to nivolumab for 2 cycles. Eight weeks after the last dose, the patient developed severe myositis complicated with spontaneous haematomain skeletalmuscle. Pathology of the skeletal muscle autopsy revealed lymphocytic infiltration. Intense immunosuppressive therapy, including high-dose corticosteroids and methotrexate, resulted in clinical success in the treatment of myositis. However, the patient died of cancer recurrence.

Conclusion

Myositis due to immunotherapy can be a fatal adverse event of ICIs, which requires close monitoring and cautious management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), such as cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) inhibition, target programmed death-1 (PD-1) and its ligand PD-L1, have been intensively investigated and developed to treat various types of cancer over the past decade [1]. Despite the fact that immunotherapy with checkpoint blockade has shown remarkable and durable responses in various cancer types, the application of checkpoint inhibitors in pancreatic cancer has been disappointing thus far [2]. In October 2015, the first combination of different ICIs (the PD-1 antibody Opdivo and the CTLA-4 antibody Yervoy) was approved for advanced malignant melanoma. Combined ICIs treatment has greatly improved the clinical outcomes of these cancers [3, 4]. However, a spectrum of autoimmune side effects, including rash, colitis, pneumonitis and endocrinopathies, was noted during clinical trials and post-marketing surveillance. These effects were referred to as immune-related adverse effects (irAEs) [5,6,7,8,9,10]. The frequency and severity of irAEs are even greater inpatients undergoing combined ICIs therapy [11,12,13,14,15,16]. Here, we report a case of fatal myositis complicated with spontaneous haematoma of the skeletal muscle after administration of Opdivo and Yervoy, which we hope will remind physicians to monitor the side effects and use these medications more discreetly.

Case report

The patient was a 71-year-old gentleman diagnosed with pancreatic adenocarcinoma who was otherwise healthy with no family and psychosocial history. His tumour was first indicated by jaundice and a suspicious mass in the caput pancreatic in June 2014 with elevated serum carbohydrate antigen 19–9 (CA199) level (160.3 U/mL). Therefore, he underwent the Whipple procedure in September 2014. Post-operative pathology showed multiple areas of moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma. BRAF mutation and a variant of BRCA2 of unknown significance were noted. PD-L1 was negative. The patient received 8 cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine and achieved a complete response in April 2015. There were no visible lesions, and his CA199 level dropped to 24 U/mL. However, tumour recurrence was suspected in November 2015 due to newly found lymph nodes with increased activity in the left supra and infra clavicle areas, porta hepatic area and peritoneal area according to positron emission tomography (PET). Treatment with the PD-1 inhibitor Opdivo (1 mg/kg) was started at a private hospital in foreign country together with capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (XELOX), Avastin and Zelboraf for 8 cycles with good tolerance, and then the patient was switched to Onyyvide, Xeloda, Avastin along with Opdivo. In August 2016, the CTLA-4 inhibitor Yervoy (3 mg/kg) was added to Opdivo for 2 cycles. Subsequent PET/CT showed decreased activity and size in lymph nodes and no evidence for recurrence.

Eight weeks after the last dose of Opdivo and Yervoy, the patient developed myalgia and myasthenia and presented to our emergency room on October 31, 2016 with a high level of creatine kinase (CK) (6235 U/L). Isozyme electrophoresis demonstrated that 95.4% of CK was creatine kinase-MM (CK-MM). However, his CK level continued to increase, and his symptoms worsened. An elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (33 mm/h) and hypersensitive C-reactive protein (3.88 mg/L) levels were detected together with positive serum anti-Ro-52 antibody. Electromyogram (EMG) indicated active myogenic damage (Additional file 1). Furthermore, biopsy of the right quadriceps femoris muscle was performed and revealed necrosis of skeletal muscle fibres and inflammationin the interstitial area and small vessels (Additional file 2). The severity of myasthenia continued to progress. Moreover, his swallowing muscles and respiratory muscles were involved, resulting in dysphagia and respiratory failure. Because the patient was able to drink water and enteral nutrition even when his symptoms were most serious, he was not intubated. Then, the patient was treated with methylprednisolone at an initial dose of 500 mg/d for 3 days starting November 10, 2016, followed by 60 mg/d intravenously. His symptoms improved over several weeks, and CK declined to normal from the highest level of 11,408 U/L.

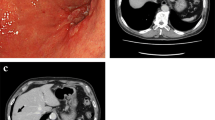

However, 4 days after the initiation of glucocorticoid treatment, the patient developed acute and progressive low back pain radiating to the left lower limb. At the same time, a dramatic drop in haemoglobin from 120 g/L to 63 g/L within 48 h was noted. The patient’s platelet count was within the normal range throughout. Radiographic imaging revealed a massive haematoma of the left psoas major muscle (Fig. 1). The patient was on a preventive anticoagulant treatment of low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) (670 U/10 kg body weight every 12 h) because of his bed confinement status and low level of plasma albumin. No dysfunction of coagulation was detected, and no trauma had ever taken place. No petechia or bruising was noted after a thorough physical examination. Bleeding was quickly stopped after withdrawal of LMWH. A computed tomography angiography was performed, which found no leakage of contrast from the vessels. Additionally, the patient’s haemoglobin level remained stable. Interventional radiology was consulted, and vascular embolism was not recommended because the culpritvessel was difficult to determine. The patient was then discharged on December 9th with tapered oral glucocorticoids. Unfortunately, he died of pancreatic adenocarcinoma recurrence 2 months later with stable myositis.

Radiographic imaging revealed a massive hematoma of the left psoas major muscle (arrow) (Enhanced abdominal CT was showed in Additional file 3)

Figure 2 shows the timeline of interventions and laboratory results after the patientwas diagnosed withpancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Timeline of interventions and laboratory results. ALT: glutamic-pyruvic transaminase, AST: cereal grass transaminase; CK: creatinekinase; CK-MB: creatine kinase-MB; cTnI: cardiac troponin I; IVIG: intravenous immunoglobulin; LDH:lactic acid dehydrogenase; LMWH: low molecular weight heparin; MP: methylprednisolone; MTX: methotrexate; Myo: myoglobin; ULN: upper limit of normal

Discussion

Myositis is rarely reported compared to other irAEs, such as dermatitis, endocrinopathies, colitis and pneumonitis. According to a previous study, the incidence of myositis in patients receiving ipilimumab plus nivolumab was 0.24% [5]. ICI-related myositis mimics primary dermatomyositis in clinical and laboratory features [17]. Most of the cases were manageable with glucocorticoids. Multi-disciplinary cooperation with rheumatologists is crucial. In our case, myositis developed after only 2 cycles of combined ICIs therapy. The progression of muscle damage was fulminant. The condition was nearly fatal. We suggest that clinicians remain vigilant for this rare irAE.

Here, we review 8 other reported cases of muscular haematoma in myositis since 1998 from the literature and summarize the clinical characteristics of muscular haematoma in myositis, including our case (Table 1). Seven out of 9 patients are above the age of 60. The median age is 64. The sex ratio is 1: 2 (male: female). This illustrates that elderly female patients are more likely to suffer from muscular haematoma. Muscles of the retroperitoneal area, including the iliopsoas muscle and psoas muscle, are more prone to spontaneous bleeding. The aetiology of the susceptibility of the iliopsoas to spontaneous haemorrhage is unclear. A proposed theory is that the iliopsoas is naturally predisposed to spontaneous intramuscular haemorrhage, as they are the strongest flexors in the body and are involved in numerous locomotive manoeuvres [25]. Seven out of 9 patients received anticoagulation treatment, both unfractionated heparin (UFH) and LMWH. There is no evidence to prove that any anticoagulant is safer than others regarding the risk of muscle bleeding. Moreover, those patients who received anticoagulant also underwent glucocorticoid pulse treatment, which may suggestmore severe myositis. This interesting coincidence makes corticosteroids truly suspicious of causing spontaneous haematoma. However, there is no literature proving a definite relationship between steroid and spontaneous haematoma. Except for our case, none of the 8 cases were diagnosed with malignancy.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report of life-threatening myositis and spontaneous muscular haematoma associated with combined ICIs therapy since pancreatic adenocarcinoma is immune quiescent. To date, checkpoint inhibition therapy has failed to elicit efficacy in patients with pancreatic cancer [26,27,28,29]. Combination regimens comprising chemotherapy and ICIs have shown initial promise in clinical trials and in animal studies, but these results need to be verified [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. We believe it was not rigorous to administer this combined treatment to pancreatic cancer patients. In addition to spontaneous haematomas, other severe complications of myositis, such as acute rhabdomyolysis, have also been reported with ipilimumab-nivolumab treatment as mere associations [17]. However, we cannot conclude that ICIs contribute to these severe complications. Nevertheless, our report emphasized the necessity of closely monitoring irAEs in patients treated with combination immunotherapy. Meanwhile, the potential danger of anticoagulation therapy in a patient treated with ICIs, especially in the elderly population, should be alerted. Thus, clarity the indication and strict clinical surveillance would be of value.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- CA199:

-

Carbohydrate antigen 19–9

- CK:

-

Creatinekinase

- CTLA-4:

-

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4

- EMG:

-

Electromyogram

- ICIs:

-

Immune checkpoints inhibitors

- irAEs:

-

Immune-related adverse effects

- LMWH:

-

Low molecular weight heparin

- MP:

-

Methylprednisolone

- PD-1:

-

Programmed death-1

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- UFH:

-

Unfractionated heparin

- XELOX:

-

Capecitabine plus oxaliplatin

References

Gatalica Z, Xiu J, Swensen J, Vranic S. Comprehensive analysis of cancers of unknown primary for the biomarkers of response to immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Eur J Cancer. 2018;94:179–86.

Rosenberg A, Mahalingam D. Immunotherapy in pancreatic adenocarcinoma-overcoming barriers to response. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2018;9(1):143–59.

Ott PA, Hodi FS, Kaufman HL, Wigginton JM, Wolchok JD. Combination immunotherapy: a road map. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5:16.

Chae YK, Arya A, Iams W, Cruz MR, Chandra S, Choi J, Giles F. Current landscape and future of dual anti-CTLA4 and PD-1/PD-L1 blockade immunotherapy in cancer; lessons learned from clinical trials with melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6(1):39.

Johnson DB, Balko JM, Compton ML, Chalkias S, Gorham J, Xu Y, Hicks M, Puzanov I, Alexander MR, Bloomer TL, et al. Fulminant myocarditis with combination immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(18):1749–55.

Le Roy A, Kempf E, Ackermann F, Routier E, Robert C, Turpin A, Marabelle A, Mateus C, Michot JM, Lambotte O. Two cases of immune thrombocytopenia associated with pembrolizumab. Eur J Cancer. 2016;54:172–4.

Marrone KA, Ying W, Naidoo J. Immune-related adverse events from immune checkpoint inhibitors. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;100(3):242–51.

Friedman CF, Snyder A. Atypical autoimmune adverse effects with checkpoint blockade therapies. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(2):206–7.

Hoadley A, Sandanayake N, Long GV. Atrophic exocrine pancreatic insufficiency associated with anti-PD1 therapy. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(2):434–5.

Zhao B, Zhao H, Zhao J. Serious adverse events and fatal adverse events associated with nivolumab treatment in cancer patients : Nivolumab-related serious/fatal adverse events. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6(1):101.

Appelbaum J, Wells D, Hiatt JB, Steinbach G, Stewart FM, Thomas H, Nghiem P, Kapur RP, Thompson JA. Bhatia S:fatal enteric plexus neuropathy after one dose of ipilimumab plus nivolumab a case. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:82.

Heinzerling L, Ott PA, Hodi FS, Husain AN, Tajmir-Riahi A, Tawbi H, Pauschinger M, Gajewski TF, Lipson EJ, Luke JJ. Cardiotoxicity associated with CTLA4 and PD1 blocking immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2016;4:50.

Reuss JE, Kunk PR, Stowman AM, Gru AA, Slingluff CL Jr, Gaughan EM. Sarcoidosis in the setting of combination ipilimumab and nivolumab immunotherapy: a case report & review of the literature. J Immunother Cancer. 2016;4:94.

Bottlaender L, Breton AL, de Laforcade L, Dijoud F, Thomas L, Dalle S. Acute interstitial nephritis after sequential ipilumumab - nivolumab therapy of metastatic melanoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5(1):57.

Salama AK, Moschos SJ. Next steps in immuno-oncology: enhancing antitumor effects through appropriate patient selection and rationally designed combination strategies. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(1):57–74.

Hantel A, Gabster B, Cheng JX, Golomb H, Gajewski TF. Severe hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in a melanoma patient treated with ipilimumab + nivolumab. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6(1):73.

Bilen MA, Subudhi SK, Gao J, Tannir NM, Tu SM, Sharma P. Acute rhabdomyolysis with severe polymyositis following ipilimumab-nivolumab treatment in a cancer patient with elevated anti-striated muscle antibody. J Immunother Cancer. 2016;4:36.

Orrell RW, Johnston HM, Gibson C, Cass RM, Griggs RC. Spontaneous abdominal hematoma in dermatomyositis. Muscle Nerve. 1998;21(12):1800–3.

Langguth DM. Haemorrhagic myositis associated with prophylactic heparin use in dermatomyositis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(4):464–5.

Higashi Y, Mera K, Kanzaki T, Kanekura T. Fatal muscle haemorrhage attributable to heparin administration in a patient with dermatomyositis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34(3):448–9.

Yamagishi M, Tajima S, Suetake A, Kawakami H, Watanabe T, Kuriyama H, Takada T, Suzuki E, Gejyo F. Dermatomyositis with hemorrhagic myositis. Rheumatol Int. 2009;29(11):1363–6.

Miwa Y, Muramatsu M, Takahashi R, Wakabayashi K, Odai T, Isozaki T, Yajima N, Kasama T. Dermatomyositis complicated with hemorrhagic shock of the iliopsoas muscle on both sides and the thigh muscle. Mod Rheumatol. 2010;20(4):420–2.

Hanawa F, Inozume T, Harada K, Andou N, Kawamura T, Shibagaki N, Shimada S. A case of dermatomyositis accompanied by spontaneous intramuscular hemorrhage despite normal coagulability. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33(11):2949–50.

Chen YH, Wu PC, Ko PY, Lin YN. Retroperitoneal hematoma mimicking exacerbation of dermatomyositis. Int Medicine (Tokyo, Japan). 2015;54(8):995–6.

Tosun A, Inal E, Keles I, Tulmac M, Tosun O, Aydin G, Orkun S. Conservative treatment of femoral neuropathy following retroperitoneal hemorrhage: a case report and review of literature. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2014;25(7):769–72.

Comin-Anduix B, Escuin-Ordinas H, Ibarrondo FJ. Tremelimumab: research and clinical development. OncoTargets Therapy. 2016;9:1767–76.

Royal RE, Levy C, Turner K, Mathur A, Hughes M, Kammula US, et al. Phase 2 trial of single agent ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4) for locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Immunother. 2010;33:828–33.

Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, Hwu WJ, Topalian SL, Hwu P, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. New England J Med. 2012;366:2455–65.

O'Reilly EM, Oh D-Y, Dhani N, Renouf DJ, Lee MA, Sun W, et al. A randomized phase 2 study of durvalumab monotherapy and in combination with tremelimumab in patients with metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (mPDAC): ALPS study. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:217.

Katz MHG, Varadhachary GR, Bauer TW, Acquavella N, Merchant NB, Le TM, et al. Preliminary safety data from a randomized multicenter phase Ib/II study of neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy (CRT) alone or in combination with pembrolizumab in patients with resectable or borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol Conf. 2017;35(15_suppl):4125–4125. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.4125.

Aglietta M, Barone C, Sawyer MB, Moore MJ, Miller WH, Bagala C, et al. A phase I dose escalation trial of tremelimumab (CP-675,206) in combination with gemcitabine in chemotherapy-naive patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:1750–5.

Kalyan A, Kircher SM, Mohindra NA, Nimeiri HS, Maurer V, Rademaker A, et al. Ipilimumab and gemcitabine for advanced pancreas cancer: a phase Ib study. J Clin Oncol Conf. 2016;34(15_suppl). https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.34.15_suppl.e15747.

Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouché O, Guimbaud R, Bécouarn Y, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1817–25.

Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, Chiorean EG, Infante J, Moore M, et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1691–703.

Weiss GJ, Blaydorn L, Beck J, Bornemann-Kolatzki K, Urnovitz H, Schutz E, et al. Phase Ib/II study of gemcitabine, nab-paclitaxel, and pembrolizumab in metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Investig New Drugs. 2018;36:96–102.

Wainberg ZA, Hochster HS, Kim E, George B, Kalyan A, Chiorean EG, et al. Phase I study of nivolumab (nivo) + nab-paclitaxel (nab-P) + gemcitabine (Gem) in advanced pancreatic cancer (APC). J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(4_suppl):298.

Borazanci EH, Jameson GS, Borad MJ, Ramanathan RK, Korn RL, Caldwell L, et al. A phase II pilot trial of nivolumab (N) + albumin bound paclitaxel (AP) + paricalcitol (P) + cisplatin (C) + gemcitabine (G) (NAPPCG) in patients with pre- viously untreated metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:358.

Thomas AM, Reena S, Jason RP, Benjamin S, Christopher WM, Shannon L, et al. IL-6 and PD-L1 antibody blockade combination therapy reduces tumour progression in murine models of pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2016;67(2):320–32.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grand from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not for profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YL and XT wrote the manuscript, collected clinical data and follow up; ZL and LC collected pathology data; YL and XT complete literature review; XZ,CB, SL and XT took care of the patient and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication in print and electronically has been obtained from the patient’s daughter.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1:

Electromyogram result.

Additional file 2:

Pathological image of biopsy of the right quadriceps femoris muscle.

Additional file 3:

Figure of enchanced CT image of haematoma of the left psoas major muscle.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Liu, Z., Zeng, X. et al. Fatal myositis and spontaneous haematoma induced by combined immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment in a patient with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. BMC Cancer 19, 1193 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-6372-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-6372-z