Abstract

Background

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) can affect functional performance and quality of life considerably. Since balance training has proven to enhance physical function, it might be a promising strategy to manage CIPN-induced functional impairments.

Methods

Fifty cancer survivors with persisting CIPN after finishing their treatment were randomly allocated to an intervention (IG) or active control group (CG). The IG did endurance plus balance training, the CG only endurance training (twice weekly over 12 weeks). Pre- and post-assessments included functional performance, cardiorespiratory fitness, vibration sense, and self-reported CIPN symptoms (EORTC QLQ-CIPN20).

Results

Intention-to-treat analyses (n = 41) did not reveal a significant group difference (CG minus IG) for sway path in semi-tandem stance after intervention (primary endpoint), adjusted for baseline. However, our per-protocol analysis of 37 patients with training compliance ≥70% revealed: the IG reduced their sway path during semi-tandem stance (− 76 mm, 95% CI -141 – -17; CG: -6 mm, 95% CI -52 – 50), improved the duration standing on one leg on instable surface (11 s, 95% CI 8–17; CG: 0 s, 95%CI 0–5) and reported decreased motor symptoms (−8points, 95% CI -18 – 0; CG: -2points 95% CI -6 – 2). Both groups reported reduced overall- (IG: -10points, 95% CI -17 – -4; CG: -6points, 95% CI -11 – -1) and sensory symptoms (IG: -7points, 95% CI -15 – 0; CG: -7points, 95% CI -15 – 0), while only the CG exhibited objectively better vibration sense (knuckle: 0.8points, 95% CI 0.3–1.3; IG: 0.0points, 95% CI -1.1 – 0.9; patella: 1.0points, 95% CI 0.4–1.6: IG: -0.8points, 95% CI -0.2 – 0.0). Furthermore, maximum power output during cardiopulmonary exercise test increased in both groups (IG and CG: 0.1 W/kg, 95% CI 0.0–0.2), but only the CG improved their jump height (2 cm, 95% CI 0.5–3.5; IG: 1 cm, 95% CI -0.4 – 3.2).

Conclusion

We suppose that endurance training induced a reduction in sensory symptoms in both groups, while balance training additionally improved patients’ functional status. This additional functional effect might reflect the IG’s superiority in the CIPN20 motor score. Both exercises provide a clear and relevant benefit for patients with CIPN.

Trial registration

German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS) number: DRKS00005419, prospectively registered on November 19, 2013.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Peripheral neuropathy symptoms often persist after chemotherapy treatment has finished, and they can significantly impair patients’ quality of life, even in the long term [1]. The prevalence of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) can total 68% during the first month after the end of chemotherapy [2], and its consequences are known to trigger excessive healthcare costs and resource use [3].

Affected patients suffer from symptoms like pain and paraesthesia, loss of sensation and proprioception in the lower extremities resulting in muscle weakness, balance problems, and gait instability may lead to a higher risk of falling [4]. Such functional impairments can substantially limit mobility [5] and even predict hospitalization or mortality [6]. Based on the ASCO guidelines, only duloxetine can currently be recommended for pain reduction in CIPN [7]. The efficacy of further pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches is not evidence-based [7]. Therefore, we pursue further effective treatment options to ensure patients’ social participation by preserving their mobility and reducing health risks that entail a prolonged need for therapy. There is cross-etiological evidence that exercising can reduce neuropathic symptoms [8]: patients with diabetic neuropathy benefit from exercising like endurance [9, 10], balance [11, 12] and multimodal training [13, 14]. Endurance training induces metabolic changes, and balance training [8] leads to neuronal adaptations and improved muscular output resulting in a better postural control [15, 16]. Concerning CIPN, exercising is generally recommended [4] but has been less evaluated [17]. Our intervention study on lymphoma patients provided initial indications about exercising and CIPN, where we speculated that especially balance exercises would reduce CIPN sensory symptoms and improve physical functioning [18]. In our subsequent pilot study, exclusively CIPN patients underwent the aforementioned intervention and benefited from exercising by approximating the posture behavior of matched healthy control subjects (data unpublished). We thus implemented the present trial to evaluate exercise effects on CIPN symptoms and functional performance. Our primary objective was to improve CIPN patients’ balance performance, hypothesizing that balance exercises would lead to a reduction in postural sway after a twelve-week intervention.

Methods

Study design and patients

Fifty cancer survivors were randomly allocated consecutively between December 2013 and November 2014 to an intervention group (IG) or active control group (CG). Randomization in blocks of 10 was based on a computer-assisted pseudo-random number generator (Research Randomizer, Version 4.0). Allocation was implemented by sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes. After obtaining patient’s consent, baseline measurement was performed and the next consecutively numbered envelope was opened afterwards.

Inclusion criteria were: reporting CIPN symptoms, completion of anti-tumor treatment, ≥18 years, a maximum 90 min’ travel time to the Medical Center – University of Freiburg, Germany, and written informed consent. Exclusion criteria were: neuropathies of different origin, severe cardiovascular diseases, instable bone metastases, and pregnancy. Pre- and post-assessments were made before (T0) and after (T1) intervention and took place at the Institute for Exercise- and Occupational Medicine, Medical Center – University of Freiburg, Germany.

Lower-extremity CIPN was clinically confirmed by assessing reflexes and vibration sense and by discrimination tests for joint position sense, temperature, and pain sensation (Table 1).

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Freiburg, conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and registered in the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS00005419).

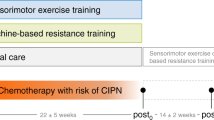

Interventions

The one-on-one training sessions took place twice per week over 12 weeks in the division of Sports Oncology in the Clinic of Internal Medicine I. Both groups underwent endurance training up to 30 min of moderate intensity below the individual anaerobic threshold (IAT) on a stationary bicycle. The IG also did 30 min’ balance training. Balance exercise sessions included three to eight exercises with three repetitions each à 20 – 30s involving progressively increasing exercise difficulty by reducing the support surface and visual input, adding motor/cognitive tasks, and instability induction [19].

For both groups, we additionally monitored exercise intensity by the perceived exertion rating scale [20, 21].

Furthermore, we controlled each patient’s blood pressure and heart rate during each training session to avoid overload and documented vital parameters, training progress and reasons for missed sessions.

Outcome measures

Functional performance

All the measurements were performed on a force plate (Leonardo Mechanograph® GRFP, Novotec Medical GmbH, Pforzheim, Germany), which determined dynamic ground reaction forces in its local and temporal progress. For balance assessments, we recorded the center of force sway path (mm) during three different stance conditions: semi-tandem stance with eyes open (STEO) (primary endpoint) and eyes closed (STEC), and monopedal stance (MSEO) over a period of 30s with a sample rate of 800 Hz. While measuring, patients were asked to stand upright and comfortably and direct their gaze onto a marked spot located at eye level on the wall. The best trial out of three was used for analysis. A reduction of sway path after exercising is associated with an improved postural control.

Additionally, we recorded the duration (max. 30s) patients could stand on one leg on a stable (MSEO) and unstable (MSEOunstable) surface, respectively.

To evaluate the lower body’s muscle power, patients performed a maximum counter-movement jump to measure maximum power output during take-off per kilogram body weight (Pmax_jump; W/kg) and jumping height (cm). Patients were instructed to jump as high as possible. The best trial of two trials was used for analysis.

Data were analyzed using Leonardo Mechanography Research-Software (Novotec Medical GmbH, Pforzheim, Germany).

CIPN symptoms and quality of life

Vibration sense was determined on the first metacarpophalangeal joint, knuckle and patella via Rydel-Seiffer tuning fork with a graduating scale from 0 (no sensitivity) to 8 (highest sensitivity); due to reliability, tests were repeated twice, the respective mean value was used for analysis. For patients’ characteristic, reduced vibration sense was defined as < 5 [22].

We used the EORTC QLQ-C30-questionnaire (European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life) to assess global quality of life (QoL). A higher score (max 100%) represents a higher quality of life [23]. The module EORTC QLQ-CIPN20 and neurotoxicity subscale (NtxS) of FACT&GOG (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy/Gynaecology Oncology Group) were used to estimate CIPN severity. For CIPN20, we calculated a sum score and five sub-scores (sensory, motor, autonomic, upper and lower extremity). Each sub-score ranges from 0 to 100, where higher scores represent more severe symptoms or impairment.

Cardiorespiratory fitness

We determined cardiorespiratory fitness by peak oxygen consumption (V̇O2peak; mL·min− 1·kg− 1), maximum power output (Pmax_CPET; W/kg) and performance at the IAT (W/kg) measured during the maximum cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET). CPET [24] including electrocardiogram and blood pressure measurement took place on an electronically-braked cycle ergometer (Ergoline 900, Bitz, Germany) in recumbent position, starting at 20 watt and increasing stepwise by 10 watt every minute until exhaustion [21]. Gas exchange and ventilation was continuously recorded by a breath-by-breath gas analysis system (Oxycon Delta, Jaeger, Hochberg, Germany). IAT was determined by analyzing the lactate concentration per step (Ergonizer, Freiburg, Germany).

Sample size and statistics

Sample size calculation is based on the primary endpoint sway path at T1 and aims to detect a mean difference of 30% (SD ± 32%) between groups according to pilot study results. For sample size purposes, sway path is calculated as % of baseline measurement. With these prerequisites, 20 patients per group are required to provide 80% power to obtain a significant study result, using the 2-sided t-test with α = 0.05. Considering a maximum dropout rate of 20%, total sample size was set to N = 50. As specified in the clinical trial protocol, our primary analysis was conducted via regression model for variable STEO at T1 as dependent variable, treatment allocation and baseline STEO as covariates. Patients on whom we had no post-randomization data were excluded from the intention-to-treat analysis (Fig. 1 Flowchart). A sensitivity analysis of the primary endpoint included the therapy-free time until study inclusion and patient age as additional covariates.

We also conducted a per-protocol analysis that excluded patients with training compliance < 70%, calculated as completed training sessions divided by planned training sessions. All variables were tested non-parametrically as the assumption of normal distribution (Shapiro-Wilk test) was not satisfied. Differences between our two subject subpopulations at T0 and T1 and differences in the groups’ delta (T1-T0) were assessed by Mann-Whitney-U-test. Intragroup differences over time were computed by Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The level of significance was set to p < .05. To estimate the treatment effect, the point estimate and 95% confidence interval (CI) of the Hodges-Lehmann’s median differences for paired groups were used. We also calculated the Phi coefficient (rφ= \( \sqrt{z2/n} \)) for effect sizes based on z-statistics of Wilcoxon- and Mann-Whitney-U test, respectively [25]. IBM SPSS software (version 24; SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used for all analyses.

Results

No adverse events were observed during the study period. As post-randomization data were unavailable on seven patients, and two patients were excluded due to recruiting failure, our intention-to-treat analyses (ITT) included 41 patients. The primary analysis linear regression model (ITT) did not reveal a sway-path group difference (CG minus IG) at T1 (estimated as 35 mm; 95%CI -30 – 101; p = .279), adjusted for baseline. The sensitivity analysis revealed that the covariates therapy-free time until study inclusion and patients’ age did not lead to a fundamentally different interpretation of our results (see Table 2 for regression analysis results).

As not all patients attained ≥70% compliance, we present a per-protocol-analysis (n = 37) to describe the treatment effect in this group (see Table 3 and the following). We noted similar baseline values in the IG and CG, except for semi-tandem stance with eyes open, monopedal stance on instable surface and jumping performance, where the CG performed better in each case (STEO: P = .049; MSEOunstable: P = .011; Pmax_jump: P = .019; Jumping height: P = .045).

Functional performance

IG’s STEO sway path decreased significantly (− 76 mm, 95%CI -141 – -17; p = .018), while the CG’s was unchanged, leading to a significant difference in groups’ delta (p = .049). STEC sway path revealed no inter- or intragroup changes. In the monopedal stance condition (MSEO sway path), both groups improved descriptively without statistical significance, but with moderate effect sizes (rφ = 0.41; rφ = 0.51, respectively). However, only the IG improved their time standing on one leg (MSEO: 1 s, 95%CI 0–7; p = .051; MSEOunstable: 11 s, 95% CI 8–17; p = .001), while the CG maintained their performance level, leading to a significant difference in groups’ delta for MSEOunstable (p = .000).

CG improved their maximum jump height significantly (2 cm, 95%CI 0.5–3.5; p = .039), while the IG’s failed to change. Maximum power (Pmax_jump) was unaltered.

CIPN symptoms and quality of life

We detected neither inter- nor intragroup differences in vibration sense measured on the first metacarpophalangeal joint (scale 0–8). However, on the knuckle, the CG increased significantly (0.8, 95% CI 0.3–1.3; p = .011) leading to a significant group difference at T1 (p = .049). Furthermore, the patella’s vibration sense improved significantly in the CG (1.0, 95% CI 0.4–1.6; p = .002), while the IG’s decreased significantly (− 0.8, 95% CI -0.2 – 0.0; p = .041), leading to a significant difference at T1 (p = .005) and in groups’ delta (p = .000).

In NtxS, the IG reported significantly alleviated CIPN symptoms (3, 95% CI 1–6; p = .015). Except for the upper extremity sub-score, CIPN20 revealed significant weakening in the IG’s CIPN symptoms (sum score: -10, 95% CI -17 – -4; p = .007; sensory score: -7, 95% CI -15 – 0; p = .028; motor score: -8, 95% CI -18 – 0; p = .006; autonomic score: -8, 95% CI -17 – 0; p = .006; lower extremity score: -13, 95% CI -19 – -4; p = .007), while the CG’s sum, sensory and lower extremity scores also decreased significantly (− 6, 95% CI -11 – -1; p = .027; − 7, 95% CI -15 – 0; p = .018; − 8, 95% CI -15 – -2; p = .014; respectively). Both groups’ global QoL improved slightly but not significantly.

Cardiorespiratory fitness

The CG significantly improved their performance at IAT after the intervention (0.1 W/kg, 95%CI 0.0–0.1; p = .020; no change for IG p = .122). Furthermore, both groups strengthened their maximum power output (IG: 0.1 W/kg, 95%CI 0.0–0.2; p = .025; CG: 0.1 W/kg, 95%CI 0.0–0.2; p = .004). However, we detected no differences in V̇O2peak.

Discussion

The aim of this randomized controlled clinical trial was to assess the effects of endurance and balance training on CIPN symptoms and the physical function of cancer survivors after treatment. Primary intention-to-treat analysis did not reveal a superiority of balance training contrary to our hypothesis. However, subsequent analysis did not entirely support this finding, since the results of per-protocol analysis (≥70% compliance) including secondary endpoints requires a detailed view. For this analysis, however, the number of patients is under the 20 patients per group required according to the power analysis. Our results may have been more convincing with a larger number of patients.

In general, balance training is known to induce neuronal adaptations and improve muscular output leading to an enhanced postural control [15, 16]. It is well known that patients with a proprioceptive deficit such as peripheral neuropathy suffer from postural instability [5], as do patients with CIPN [26,27,28,29,30,31]. However, only four randomized controlled trials have been published on the effects of balance interventions in CIPN patients [18, 32,33,34]. Our trial showed that our IG prolonged their standing time on one leg, and reduced their sway path in the semi-tandem stance with eyes open – factors associated with better postural control [28]. Even our CG slightly improved their balance performance in the monopedal stance without having practiced this task. This improvement could be traced back to a general increase in leg-muscle strength induced by endurance training, a factor also reflected by our finding that both groups enhanced their maximum power output during CEPT. However, only CG’s jumping performance increased. Since both groups formally completed the same endurance training, such a change should probably have been observed in both groups. It is conceivable that the CG engaged more intensively in their endurance training, since their training program consisted exclusively of endurance training, which may unconsciously lead to more intense training, while the IG may have considered the 30-min endurance exercise to be a mere warm-up. A further explanatory viewpoint lies in the baseline differences; the CG exhibited greater power capacity already at T0, ie, Pmax_jump and jump height, than did the IG.

This baseline difference may be attributable to the CG’s younger age, since the rate of force development is known to decline with age [35]. The CG’s younger age may also be responsible for the significant baseline difference in two balance tasks, MSEOunstable and STEO. Their predominant initial functional status may also be because they received a lower amount of neurotoxic agents.

In the eyes-closed condition in the balance tasks, we detected no inter- or intragroup differences, but the sway path increased considerably after closing the eyes. The increase in postural sway when visual information is unavailable is more pronounced in patients with neuropathy than in healthy subjects [5]. These patients may rely more on vestibular signals, which are known to carry a larger amount of noise [36] than on diminished proprioception to stabilize the posture. At this point, we cannot conclusively clarify how severely diminished our patients’ proprioception was, as we did not compare their balance performance to healthy subjects, especially the rise in sway from eyes open to closed. Most of our patients suffered from a reduced vibration sense and reported having more sensory than motor symptoms. Axon degeneration in unmyelinated distal nerve endings seems to be the central pathology of CIPN [37], responsible especially for sensory symptoms [38]. However, we assume that stimulus conduction is not completely dysfunctional: large myelinated nerve fibers carrying proprioceptive information and inducing muscular output might be less affected. Additionally, exercising may have stimulated the use of less damaged pathways. The increase in maximum power output in both groups and their improvements in balance performance might support this hypothesis and indicate that neuromuscular adaptation is possible. However, we observed no improvements in the eyes-closed conditions, which made us conclude that patients did not change their posture strategy towards reducing vestibular in favor of proprioceptive cues. We thus suggest focusing even more strongly on exercises without visual input during training. Being aware that analyzing CIPN20 sub-scores remains controversial [39], our motor-score results may reflect neuromuscular adaptation, as our IG improved considerably. Interestingly, both groups experienced reduced sensory symptoms and greater improvements in their lower extremities, since both exercises obviously targeted the lower body more strongly than the upper. However, objectively, only in the CG did we detect a significantly improved vibration sense from proximal to distal - probably attributable to their lower exposure to neurotoxic agents. Animal models have shown that increased blood flow, and an enhanced overall metabolic rate thanks to endurance training might result in higher levels of neurotrophic factors that may induce nerve regeneration [40, 41] and thus possibly reduce sensory symptoms. Furthermore, the anti-inflammatory effect of exercise might have contributed to weaker sensory symptoms [41].

Endurance training did not just affect CIPN-specific symptoms - it also resulted in improved performance in the CG’s IAT, presumably because of their more intensive endurance training as mentioned above. This increase in endurance capacity was not confirmed in our V̇O2peak findings. Both groups improved their maximum performance during CPET, possibly due to a general strength increase. This strength increase is also apparent in the CG’s jump height, but here without affecting power output. Muscular power output, as jumping requires, is strongly associated with mobility and functional ability [35], factors impaired in CIPN patients. We thus propose to focus also on power training to alleviate functional disabilities in CIPN patients [42] and to counteract the CIPN-induced acceleration of neuromuscular degeneration.

The fact that both groups showed improvements suggests that both interventions are potentially effective in addressing different aspects of CIPN. However, the reader should take note that a placebo effect cannot be definitively ruled out in this study. As other RCTs have also demonstrated positive effects in their intervention groups by including an inactive control group [e.g. 32,34], we assume that the improvements we observed are genuine effects rather than placebo effects. Furthermore, we suppose that group differences in patients’ characteristic, i.e. age and amount of neurotoxic agents, may have influenced study results as discussed above. We therefore propose to stratify randomization according to those factors.

Conclusions

We assume that endurance training contributed to a reduction in sensory symptoms in our study patients, while the balance part additionally affected the neuromuscular system relevant to patients’ functional status. This additional effect might reflect the IG’s superiority in the CIPN20 motor score, as well as in NtxS. However, we suspect that a larger sample is needed to reveal stronger group differences. Furthermore, we propose to integrate a third study arm with no physical intervention, and to expand upon CIPN diagnostics. We conclude that both exercises present a clear and relevant benefit for patients with CIPN by improving their functional status and alleviating CIPN symptoms. As pharmacological treatment options are very limited, these exercise interventions can be considered an effective non-pharmacological treatment approach. We are convinced that neuromuscular adaptation is possible despite CIPN, and that it’s never too late to start exercising.

Abbreviations

- CG:

-

Control group

- CIPN:

-

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy

- CIPN20:

-

Module of EORTC quality of life questionnaire

- CPET:

-

Cardiopulmonary exercise test

- IAT:

-

Individual anaerobic threshold

- IG:

-

Intervention group

- MSEO :

-

Monopedal stance

- MSEOunstable :

-

Monopedal stance on an unstable surface

- NtxS:

-

Neurotoxicity subscale of FACT&GOG

- Pmax_CPET :

-

Maximum power output during cardiopulmonary exercise test

- Pmax_jump :

-

Maximum power output during take-off

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- STEC :

-

Semi-tandem stance with eyes closed

- STEO :

-

Semi-tandem stance with eyes open

- W:

-

Watt

References

Mols F, Beijers T, Vreugdenhil G. Van de poll-Franse L. chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy and its association with quality of life: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(8):2261–9.

Seretny M, Currie GL, Sena ES, Ramnarine S, Grant R, MacLeod MR, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and predictors of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 2014;155(12):2461–70.

Pike CT, Birnbaum HG, Muehlenbein CE, Pohl GM, Natale RB. Healthcare costs and workloss burden of patients with chemotherapy-associated peripheral neuropathy in breast, ovarian, head and neck, and nonsmall cell lung cancer. Chemother Res Pract. 2012;2012:913848.

Winters-Stone KM, Horak F, Jacobs PG, Trubowitz P, Dieckmann NF, Stoyles S, et al. Falls, functioning, and disability among women with persistent symptoms of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(23):2604–12.

van Schie CHM. Neuropathy: mobility and quality of life. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2008;24(Suppl 1):45–51.

Brown JC, Harhay MO, Harhay MN. Physical function as a prognostic biomarker among cancer survivors. Br J Cancer. 2015;112:194–8.

Hershman DL, Lacchetti C, Dworkin RH, Smith EML, Bleeker J, Cavaletti G, et al. Prevention and Management of Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(18):1941–67.

Streckmann F, Zopf EM, Lehmann HC, May K, Rizza J, Zimmer P, et al. Exercise intervention studies in patients with peripheral neuropathy: a systematic review. Sports Med Auckl NZ. 2014;44(9):1289–304.

Balducci S, Iacobellis G, Parisi L, Di Biase N, Calandriello E, Leonetti F, et al. Exercise training can modify the natural history of diabetic peripheral neuropathy. J Diabetes Complicat. 2006;20(4):216–23.

Dixit S, Maiya AG, Shastry BA. Effect of aerobic exercise on peripheral nerve functions of population with diabetic peripheral neuropathy in type 2 diabetes: a single blind, parallel group randomized controlled trial. J Diabetes Complicat. 2014;28(3):332–9.

Song CH, Petrofsky JS, Lee SW, Lee KJ, Yim JE. Effects of an exercise program on balance and trunk proprioception in older adults with diabetic neuropathies. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2011;13(8):803–11.

Richardson J, Sandman D, Vela S. A focused exercise regimen improves clinical measures of balance in patients with peripheral neuropathy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82(2):205–9.

Allet L, Armand S, de Bie RA, Golay A, Monnin D, Aminian K, et al. The gait and balance of patients with diabetes can be improved: a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia. 2010;53(3):458–66.

Sartor CD, Watari R, Pássaro AC, Picon AP, Hasue RH, Sacco IC. Effects of a combined strengthening, stretching and functional training program versus usual-care on gait biomechanics and foot function for diabetic neuropathy: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:36.

Taube W, Gruber M, Gollhofer A. Spinal and supraspinal adaptations associated with balance training and their functional relevance. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2008;193(2):101–16.

Zech A, Hübscher M, Vogt L, Banzer W, Hänsel F, Pfeifer K. Balance training for neuromuscular control and performance enhancement: a systematic review. J Athl Train. 2010;45(4):392–403.

Duregon F, Vendramin B, Bullo V, Gobbo S, Cugusi L, Di Blasio A, et al. Effects of exercise on cancer patients suffering chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy undergoing treatment: a systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2018;121:90–100.

Streckmann F, Kneis S, Leifert JA, Baumann FT, Kleber M, Ihorst G, et al. Exercise program improves therapy-related side-effects and quality of life in lymphoma patients undergoing therapy. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(2):493–9.

Granacher U, Muehlbauer T, Taube W, Gollhofer A, Gruber M. Sensorimotor Training. In: Cardinale M, Newton R, Nosaka K, editors. Strength and conditioning: biological principles and practical applications. San Francisco: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011. p. 399.

Borg G. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1982;14(5):377–81.

Scharhag-Rosenberger F, Becker T, Streckmann F, Schmidt K, Berling A, Bernardi A, et al. Studien zu körperlichem Training bei onkologischen Patienten: Empfehlungen zu den Erhebungsmethoden. Dtsch Z Für Sportmed. 2014;65(11):304–13.

Pestronk A, Florence J, Levine T, Al-Lozi MT, Lopate G, Miller T, et al. Sensory exam with a quantitative tuning fork: rapid, sensitive and predictive of SNAP amplitude. Neurology. 2004;62(3):461–4.

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365–76.

Wasserman. Principles of Exercise Testing & Interpretation: including pathophysiology and clinical applications, vol. 586. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999.

Fritz CO, Morris PE, Richler JJ. Effect size estimates: current use, calculations, and interpretation. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2012;141(1):2–18.

Wampler MA, Topp KS, Miaskowski C, Byl NN, Rugo HS, Hamel K. Quantitative and clinical description of postural instability in women with breast Cancer treated with Taxane chemotherapy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(8):1002–8.

Tofthagen C, Overcash J, Kip K. Falls in persons with chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(3):583–9.

Kneis S, Wehrle A, Freyler K, Lehmann K, Rudolphi B, Hildenbrand B, et al. Balance impairments and neuromuscular changes in breast cancer patients with chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Clin Neurophysiol. 2016;127(2):1481–90.

Herman HK, Monfort SM, Pan XJ, Chaudhari AMW, Lustberg MB. Effect of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy on postural control in cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(Suppl 5):128.

Marshall TF, Zipp GP, Battaglia F, Moss R, Bryan S. Chemotherapy-induced-peripheral neuropathy, gait and fall risk in older adults following cancer treatment. J Cancer Res Pract. 2017;4(4):134–8.

Monfort SM, Pan X, Patrick R, Ramaswamy B, Wesolowski R, Naughton MJ, et al. Gait, balance, and patient-reported outcomes during taxane-based chemotherapy in early-stage breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;164(1):69–77.

Schwenk M, Grewal GS, Holloway D, Muchna A, Garland L, Najafi B. Interactive sensor-based balance Training in older Cancer patients with chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a randomized controlled trial. Gerontology. 2016;62(5):553–63.

Zimmer P, Trebing S, Timmers-Trebing U, Schenk A, Paust R, Bloch W, et al. Eight-week, multimodal exercise counteracts a progress of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy and improves balance and strength in metastasized colorectal cancer patients: a randomized controlled trial. Support Care Cancer. 2017;26(2):615–24.

Streckmann F, Lehmann HC, Balke M, Schenk A, Oberste M, Heller A, et al. Sensorimotor training and whole-body vibration training have the potential to reduce motor and sensory symptoms of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy-a randomized controlled pilot trial. Support Care Cancer. 2018. [Epub ahead of print].

Vandervoort AA. Aging of the human neuromuscular system. Muscle Nerve. 2002;25(1):17–25.

van der Kooij H, Peterka RJ. Non-linear stimulus-response behavior of the human stance control system is predicted by optimization of a system with sensory and motor noise. J Comput Neurosci. 2011;30(3):759–78.

Fukuda Y, Li Y, Segal RA. A mechanistic understanding of axon degeneration in chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Front Neurosci. 2017;11:481.

Han Y, Smith MT. Pathobiology of cancer chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN). Front Pharmacol. 2013;4:156.

Kieffer JM, Postma TJ, Van de Poll-Franse L, Mols F, Heimans JJ, Cavaletti G, et al. Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the EORTC chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy questionnaire (QLQ-CIPN20). Qual Life Res. 2017;26(11):2999–3010.

Park J-S, Höke A. Treadmill exercise induced functional recovery after peripheral nerve repair is associated with increased levels of neurotrophic factors. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e90245.

Cooper MA, Kluding PM, Wright DE. Emerging relationships between exercise, sensory nerves, and neuropathic pain. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:372.

Beijersbergen CMI, Granacher U, Gäbler M, DeVita P, Hortobágyi T. Power training-induced increases in muscle activation during gait in old adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017;49(11):2198–205.

Acknowledgements

We thank all patients who participated in this study. We gratefully acknowledge the cooperation and training implementation of sports- and physiotherapists of the Sports Oncology division in Department of Medicine I, Medical Center – University of Freiburg, especially Isabel Weinstein, René Schilling, and Simon Schneider for study assistance.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from Janssen-Cilag GmbH (grant number 26866138MMY4065). The funder neither played a role in the study design nor in data collection, analysis and interpretation, the writing process of the manuscript or the decision to submit for publication.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within this article. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SK and AW participated in the design of the study, the obtaining of funding, the data collection, the analysis and interpretation of the data and drafted the manuscript. JM recruited patients, collected data, implemented training sessions, prepared data for statistical analyses, and participated in the analysis and interpretation of the data. CM participated in the design of the study and supervised the neurological methods. GI participated in the design of the study, the analysis and interpretation of the data and conducted statistical analysis. AG participated in the design of the study. HB participated in the design of the study and the obtaining of funding. All authors provided comments and critical revisions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Freiburg (399/13). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kneis, S., Wehrle, A., Müller, J. et al. It’s never too late - balance and endurance training improves functional performance, quality of life, and alleviates neuropathic symptoms in cancer survivors suffering from chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: results of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer 19, 414 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-5522-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-5522-7