Abstract

Background

The anticancer immune response has been reported to correlate with cancer progression. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), which are one of the indicators of host immunity, affect the tumor growth, metastasis and chemoresistance. Both TILs in the primary tumor and those in the metastatic tumor have been reported to be a useful predictor of the survival and therapeutic outcome. However, the correlation between the density of TILs in the primary and metastatic tumor is unclear. The aim of this study was to elucidate the correlation between the density of TILs in the primary and metastatic tumor.

Methods

A total of 24 patients with stage IV colorectal cancer who underwent concurrent resection of the primary tumor and liver metastasis were enrolled in order to assess the correlation between the density of TILs in the primary tumor and that in the metastatic tumor. Hematoxylin and eosin (HE)-stained tumor sections were used for the evaluation of TILs. The density of TILs was assessed by the measurement of the area occupied by mononuclear inflammatory cells over the total stromal area at the invasive margin. In addition, to evaluate TIL subsets and the activation/suppression status of the lymphocytes, immunohistochemistry for CD4, CD8, Forkhead boxprotein P3 (FOXP3), programmed cell death 1 (PD-1), cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA4), inducible T-cell co-stimulator (ICOS), Glucocorticoid induced tumor necrosis factor receptor related protein (GITR), Human Leukocyte Antigen - antigen D Related (HLA-DR) and Granzyme B was performed, and the number of immunoreactive lymphocytes was counted.

Results

According to the evaluation using the HE-stained sections, the density of tumor-infiltrating mononuclear inflammatory cells in the primary tumor was significantly associated with that in the metastatic tumor. In addition, according to the immunohistochemistry evaluation, the density of CD4+, CD8+ and FOXP3+ TILs in the primary tumor and that in the metastatic tumor were significantly correlated with that in the metastatic tumor. Furthermore, the activation/suppression marker values of the lymphocytes (i.e., such as PD-1, ICOS, Granzyme B and the PD-1/CD8 ratio) in the primary tumor were correlated with values in the metastatic tumor.

Conclusions

The local immune status of the primary tumor was revealed to be similar to that of the metastatic tumor. This suggests that the evaluation of the local immunity of the primary tumor may be a substitute for the evaluation of the local immunity of the metastatic lesion. Therefore, information on the primary tumor may be useful when considering treatment strategies for metastatic lesions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The immune status of the host has been recognized to be correlated with the cancer progression in patients with various types of cancer. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), which are one of the indicators of host immunity, affect the tumor growth, metastasis and chemoresistance. Regarding the primary tumor, a high density of TILs was revealed to be correlated with better survival rates [1,2,3], and TILs were reported to be superior to TNM classification as a predictor of the survival in patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) [2]. In addition, a high density of TILs was also reported to be correlated with a better efficacy of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer [4].

TILs in the metastatic tumor as well as those in the primary tumor were reported to be a useful predictor of the therapeutic outcome, although relatively few reports on TILs in metastatic tumors have been published compared to reports on TILs in primary tumors. A high density of TILs in the metastatic tumor was reported to be correlated with better relapse-free and overall survival rates after resection of the metastatic tumor [5, 6] and a better chemotherapeutic outcome [7]. However, the correlation between the local immune status of the primary tumor and that of the metastatic tumor has been unclear.

The aim of this study was to assess the correlation between the local immune status of the primary tumor and that of the metastatic tumor.

Methods

Patients

We retrospectively reviewed a database of 24 patients with stage IV CRC who underwent concurrent resection of the primary tumor and the metastatic liver tumor at the Department of Surgical Oncology of Osaka City University between 2003 and 2016. Patients who underwent preoperative therapy, such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy, were excluded from this study.

Selection of the metastatic liver tumor for an evaluation

In case of multiple liver metastases, we selected the largest metastatic tumor for the evaluation of TILs.

The evaluation of TILs using stained sections

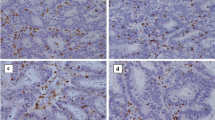

The density of TILs in hematoxylin and eosin (HE)-stained sections was evaluated according to the recommendations proposed by an International TILs Working Group [8]. In brief, the density of TILs was assessed by the measurement of the area occupied by mononuclear inflammatory cells over the total stromal area at the invasive margin (Fig. 1). Only the stromal area was evaluated, and areas occupied by cancer cells were excluded for the evaluation. A full assessment of average TILs was used, and hotspots did not receive focus. We set 50% as the cut-off value for the evaluation of TILs using the HE-stained section according to the verification study of the recommendations proposed by an International TILs Working Group [9] and classified the patients into high- and low-TIL groups based on the cut-off value.

Representative pictures of intratumoral inflammatory cell infiltration by hematoxylin and eosin staining. Low density of inflammatory cell infiltration in the primary tumor (a: × 100, b: × 400). High density of inflammatory cell infiltration in the primary tumor (c: × 100, d: × 400). Low-density inflammatory cell infiltration in the metastatic tumor (e: × 100, f: × 400). High-density inflammatory cell infiltration in the metastatic tumor (g: × 100, h: × 400)

Immunohistochemistry

Surgically resected specimens for all enrolled patients were retrieved to perform the immunohistochemistry. Immunohistochemistry was done as previously described [10]. Primary specific antibodies for CD4 (4B12, 1:80 dilution; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), CD8 (C8/144B, 1:100 dilution; Dako), FOXP3 (236/E7, 1:100 dilution; Abcam, Cambrige, UK), PD-1 (NAT105, 1:50 dilution; Abcam), CTLA4 (UMAB249, 1:200 dilution; OriGene Technologies, Rockville, US), ICOS (EPR20560, 1:500 dilution; Abcam), GITR (D919D, 1:400 dilution; Cell Signaling Technologies, Beverly, US), HLA-DR (L243, 1:100 dilution; Novus Biologicals, Abingdon, UK) and Granzyme B (EPR8260, 1:200 dilution; Abcam) were prepared as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

An immunohistochemical evaluation

An immunohistochemical evaluation was carried out by two independent pathologists who were blinded to the clinical information. The number of immunoreactive lymphocytes at the invasive margin was counted with a light microscope in a randomly selected field at a magnification of 400 (Fig. 2). The mean of values obtained in five different areas was used for the data analysis. We then classified patients into high- and low-TIL subset groups according to each median value.

Statistical analyses

The significance of the correlations between TILs and the clinicopathological characteristics were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test. Associations between the density of the TILs in the primary tumor and that in the metastatic tumor were evaluated by Fisher’s exact test, Wilcoxon’s test and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. All of the statistical analyses were conducted using the JMP® 13.0.0 software program (2016 SAS institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). P values of < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Patient characteristics

The characteristics of the patients who underwent concurrent resection of the primary tumor and liver metastases are listed in Table 1. The distribution of the number of liver metastasis was as follows: 1 in 16 patients, 2 in 4 patients, and ≥ 3 in 4 patients. The median size of the largest metastatic tumor was 2.4 cm (range: 0.4–8.0 cm).

Correlations between the density of TILs and the characteristics of the metastatic liver tumor

The densities of the TILs did not correlate with the characteristics of the metastatic liver tumor, such as the number and diameter (Table 2).

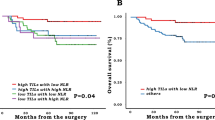

Correlation between the density of TILs in the primary and metastatic tumors

According to the evaluation of TILs using the HE-stained sections, among the nine cases with high-TILs in the primary tumor, seven cases (77.8%) were judged as having high-TILs in the metastatic tumor. Furthermore, among the fifteen cases with low-TILs in the primary tumor, thirteen cases (86.7%) were judged to have low-TILs in the metastatic tumor. The density of TILs in the primary tumor was significantly associated with that in the metastatic tumor (p = 0.003) (Table 3). The median number of CD4+, CD8+, FOXP3+ TILs in the primary and metastatic tumors is shown in Table 4. Although the median value of each of the TIL subsets was higher in the primary tumor than in the metastatic tumor, significant differences were observed in only FOXP3 (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the number of CD4+, CD8+ and FOXP3+ TILs in the primary tumor was also significantly associated with these numbers in the metastatic tumor (r = 0.634, p = 0.001; r = 0.700, p < 0.001; r = 0.559, p = 0.006, respectively) (Fig. 4).

The correlation between the number of TIL subsets in the primary tumor and that in the metastatic tumor (a: CD4, b: CD8, c: FOXP3). The numbers of CD4+, CD8+ and FOXP3+ TILs in the primary tumor was significantly associated with those in the metastatic tumor (r = 0.634, p = 0.001, r = 0.700, p < 0.001, r = 0.559, p = 0.006, respectively)

The correlation between the activation/suppression marker values in the primary and metastatic tumors

The median activation/suppression marker values (including PD-1+, CTLA4+, ICOS+, GITR+, HLA-DR+, and Granzyme B+ TILs) in the primary and metastatic tumors are shown in Table 5. The median values of CTLA4+, ICOS+, and GITR+ TILs in the primary tumor were significantly higher than those in the metastatic tumor (Fig. 5). Furthermore, the number of ICOS+, Granzyme B+ TILs and the PD-1/CD8 ratio in the primary tumor were significantly correlated with the values in the metastatic tumor (r = 0.649, p = 0.001; r = 0.426, p = 0.038; r = 0.498, p = 0.013, respectively), and the number of PD-1+ TILs tended to be correlated with that in the metastatic tumor (r = 0.387, p = 0.062) (Fig. 6).

The comparison of the activation/suppression values of the primary and metastatic tumors (a: PD-1, b: CTLA4, c: ICOS, d: GITR, e: HLA-DR, f: Granzyme B, g: the PD-1/CD8 ratio, h: the FOXP3/CD4 ratio). The values of CTLA4, ICOS and GITR (activation/suppression markers) in the primary tumor were significantly higher than those in the metastatic tumor (*: p < 0.05)

The correlation between the activation/suppression marker values of the primary and metastatic tumors (a: PD-1, b: CTLA4, c: ICOS, d: GITR, e: HLA-DR, f: Granzyme B, g: the PD-1/CD8 ratio, h: the FOXP3/CD4 ratio). The values of ICOS+, Granzyme B+ TILs, and the PD-1/CD8 ratio in the primary tumor were significantly correlated with those in the metastatic tumor (r = 0.649, p = 0.001, r = 0.426, p = 0.038, r = 0.498, p = 0.013, respectively)

Discussion

In this study, the local immune status of the primary tumor was found to be similar to that of the metastatic tumor in relation to the anticancer immunity. According to the evaluation using the HE-stained sections, the density of tumor-infiltrating mononuclear inflammatory cells in the primary tumor was significantly associated with that in the metastatic tumor. Furthermore, according to an evaluation using immunohistochemistry, the density of TIL subsets, such as CD4+, CD8+ and FOXP3+ TILs, in the primary tumor was significantly associated with that in the metastatic tumor. Furthermore, the density of PD-1+, ICOS+ and Granzyme B+ TILs, a marker of immune escape/activation, in the primary tumor was associated with that in the metastatic tumor.

TILs, which reflect the immune response of the host, are a useful biomarker for predicting the survival and therapeutic outcomes in patients with various cancers, including colorectal, breast, lung, gastric and esophageal cancer, and a number of reports on TILs have been published [11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. However, most of them concerned the TILs in the primary tumor, and very few reports have examined TILs in the metastatic tumor. As to the reason for this discrepancy in focus, resection of the metastatic tumor is included in the therapeutic strategy in CRC [18], while resection of the metastatic tumor is not included in the therapeutic strategy in various other types of cancer, such as gastric cancer and pancreatic cancer [19, 20]. Furthermore, the rate of surgical indication is quite low, even in cases of metastatic CRC [21]. Therefore, relatively few samples of metastatic tumor have been made available, resulting in markedly fewer reports on the TILs in metastatic tumors than on the TILs in primary tumors.

Control of the metastatic lesion is very important as a factor related to the prognosis in metastatic CRC. The treatment most often used for unresectable distant metastatic tumor is chemotherapy, and the density of TILs was reported to affect the chemotherapeutic effectiveness. Therefore, it is important to grasp the local immune status of the metastatic lesion in patients with unresectable metastatic CRC. However, it is not easy to collect tissue samples of the metastatic lesion with minimal invasion in clinical practice, making it difficult to grasp the local immune status of the metastatic lesion. In this study, the density of TILs in the metastatic tumor was revealed to have no relationships with the number or size of the metastatic tumor but was shown to be similar to the density of TILs in the primary tumor, as in a few past reports [5]. Furthermore, the activation/suppression status of the lymphocytes in the primary tumor was similar to that in the metastatic tumor. Although it did not apply to all of the markers, some of the activation/suppression marker values (i.e., ICOS and Granzyme B) of the primary tumor were significantly correlated with those of the metastatic tumor. In addition, the PD-1/CD8 ratio—which has been reported to reflect the immunosuppressive status in the cancer microenvironment [10] in the primary tumor was correlated with that in the metastatic tumor. Thus, it was considered that in addition to the density of the TIL subsets, the activation/suppression status of the lymphocytes of the primary tumor was associated with that of the metastatic tumor. These results supported our claim that the local immune statuses of the primary and metastatic tumors were associated with each other. Thus, the density of TILs in the primary tumor may be a surrogate marker for the density of TILs in the metastatic tumor. The results obtained in this study support the claim that the local immune status of the primary tumor is associated with the efficacy of the chemotherapy, which was reported in our previous report [22]. It may be possible to predict the chemotherapeutic efficacy on the metastatic tumor by evaluating the density of TILs in the primary tumor, even if the local immune status of the metastatic tumor cannot be evaluated. The evaluation of the density of TILs in the primary tumor may enable clinicians to stratify the patients who can expect the conversion surgery or the patients who need intensive chemotherapy.

In previous reports, the number of the TILs in the primary tumor was reported to be greater than that in the metastatic tumor. In the present study, the median number of TIL subsets in the primary tumor was greater than that in the metastatic tumor. However, a significant difference was found with respect to FOXP3. We considered that this was because of the small number of cases. On the other hand, the comparison of the activation status of the lymphocytes between the primary tumor and the metastatic tumor was not clarified in this study. Both of the activation and the suppression marker values in the primary tumor were greater than those in the metastatic tumor. This is a subject for future analysis.

There are several points to consider in evaluating the density of TILs in the metastatic tumor in this study. First, the patients with disease recurrence after the curative resection of the primary tumor or the patients who underwent two-stage hepatectomy for synchronous liver metastasis were excluded in this study, because the cancer microenvironment, including the local immune status may change with the lapse of time [23]. That is, in this study, only the patients who underwent concurrent resection of the primary tumor and the metastatic lesion were enrolled. Second, only the patients with no neoadjuvant therapy were enrolled in this study, because the local immune status may change in response to chemotherapy and radiotherapy [24, 25]. Third, the same organ should be chosen when evaluating the density of TILs in the metastatic tumor, as the density of TILs may differ depending on the metastatic organ [26]. Therefore, the subjects were limited to the patients with liver metastases in this study.

Several limitations associated with the present study warrant mention. First, we evaluated a relatively small number of patients, and the study design was retrospective. Second, as mentioned in the previous reports regarding TILs, problems such as the heterogeneity and the optimal cut-off value remain unsolved. Third, whether or not all metastatic tumors have a similar immune status remains unclear, as we evaluated only the largest tumor in cases of multiple liver metastases.

Conclusions

The local immune status of the primary tumor was revealed to be similar to that of the metastatic tumor. This suggests that the evaluation of the local immunity of the primary tumor may be a substitute for the evaluation of the local immunity of the metastatic lesion. Therefore, information on the primary tumor may be useful when considering treatment strategies for metastatic lesions.

Abbreviations

- CRC:

-

Colorectal cancer

- CTLA4:

-

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4

- FOXP3:

-

Forkhead boxprotein P3

- GITR:

-

Glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor related protein

- HE:

-

Hematoxylin and eosin

- HLA-DR:

-

Human Leukocyte Antigen - antigen D Related

- ICOS:

-

Inducible T-cell co-stimulator

- PD-1:

-

Programmed cell death 1

- TILs:

-

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

References

Huh JW, Lee JH, Kim HR. Prognostic significance of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes for patients with colorectal cancer. Arch Surg. 2012;147:366–72.

Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez-Cabo F, Kirilovsky A, Mlecnik B, Lagorce-Pagès C, Tosolini M, Camus M, Berger A, Wind P, Zinzindohoué F, Bruneval P, Cugnenc PH, Trajanoski Z, Fridman WH, Pagès F. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313:1960–4.

Teng F, Mu D, Meng X, Kong L, Zhu H, Liu S, Zhang J, Yu J. Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) before and after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and its clinical utility for rectal cancer. Am J Cancer Res. 2015;5:2064–74.

Yasuda K, Nirei T, Sunami E, Nagawa H, Kitayama J. Density of CD4(+) and CD8(+) T lymphocytes in biopsy samples can be a predictor of pathological response to chemoradiotherapy (CRT) for rectal cancer. Radiat Oncol. 2011;6:49.

Lee WS, Kang M, Baek JH, Lee JI, Ha SY. Clinical impact of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes for survival in curatively resected stage IV colon cancer with isolated liver or lung metastasis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:697–702.

Kwak Y, Koh J, Kim DW, Kang SB, Kim WH, Lee HS. Immunoscore encompassing CD3+ and CD8+ T cell densities in distant metastasis is a robust prognostic marker for advanced colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:81778–90.

Halama N, Michel S, Kloor M, Zoernig I, Benner A, Spille A, Pommerencke T, von Knebel DM, Folprecht G, Luber B, Feyen N, Martens UM, Beckhove P, Gnjatic S, Schirmacher P, Herpel E, Weitz J, Grabe N, Jaeger D. Localization and density of immune cells in the invasive margin of human colorectal cancer liver metastases are prognostic for response to chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2011;71:5670–7.

Salgado R, Denkert C, Demaria S, Sirtaine N, Klauschen F, Pruneri G, Wienert S, Van den Eynden G, Baehner FL, Penault-Llorca F, Perez EA, Thompson EA, Symmans WF, Richardson AL, Brock J, Criscitiello C, Bailey H, Ignatiadis M, Floris G, Sparano J, Kos Z, Nielsen T, Rimm DL, Allison KH, Reis-Filho JS, Loibl S, Sotiriou C, Viale G, Badve S, Adams S, Willard-Gallo K, Loi S, International TILs Working Group 2014. The evaluation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in breast cancer: recommendations by an international TILs working group 2014. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:259–71.

Swisher SK, Wu Y, Castaneda CA, Lyons GR, Yang F, Tapia C, Wang X, Casavilca SA, Bassett R, Castillo M, Sahin A, Mittendorf EA. Interobserver agreement between pathologists assessing tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in breast Cancer using methodology proposed by the international TILs working group. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:2242–8.

Shibutani M, Maeda K, Nagahara H, Fukuoka T, Nakao S, Matsutani S, Hirakawa K, Ohira M. The prognostic significance of the tumor-infiltrating programmed cell Death-1+ to CD8+ lymphocyte ratio in patients with colorectal Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2017;37:4165–72.

Hadrup S, Donia M, Thor Straten P. Effector CD4 and CD8 T cells and their role in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Microenviron. 2013;6:123–33.

Kim Y, Bae JM, Li G, Cho NY, Kang GH. Image analyzer-based assessment of tumor-infiltrating T cell subsets and their prognostic values in colorectal carcinomas. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0122183.

Denkert C, Loibl S, Noske A, Roller M, Müller BM, Komor M, Budczies J, Darb-Esfahani S, Kronenwett R, Hanusch C, von Törne C, Weichert W, Engels K, Solbach C, Schrader I, Dietel M, von Minckwitz G. Tumor-associated lymphocytes as an independent predictor of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:105–13.

Wang K, Xu J, Zhang T, Xue D. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in breast cancer predict the response to chemotherapy and survival outcome: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:44288–98.

Liu H, Zhang T, Ye J, Li H, Huang J, Li X, Wu B, Huang X, Hou J. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes predict response to chemotherapy in patients with advance non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2012;61:1849–56.

Choi Y, Kim JW, Nam KH, Han SH, Kim JW, Ahn SH, Park DJ, Lee KW, Lee HS, Kim HH. Systemic inflammation is associated with the density of immune cells in the tumor microenvironment of gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:602–11.

Noble F, Mellows T, McCormick Matthews LH, Bateman AC, Harris S, Underwood TJ, Byrne JP, Bailey IS, Sharland DM, Kelly JJ, Primrose JN, Sahota SS, Bateman AR, Thomas GJ, Ottensmeier CH. Tumour infiltrating lymphocytes correlate with improved survival in patients with oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2016;65:651–62.

Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Adam R, Sobrero A, Van Krieken JH, Aderka D, Aranda Aguilar E, Bardelli A, Benson A, Bodoky G, Ciardiello F, D'Hoore A, Diaz-Rubio E, Douillard JY, Ducreux M, Falcone A, Grothey A, Gruenberger T, Haustermans K, Heinemann V, Hoff P, Köhne CH, Labianca R, Laurent-Puig P, Ma B, Maughan T, Muro K, Normanno N, Österlund P, Oyen WJ, Papamichael D, Pentheroudakis G, Pfeiffer P, Price TJ, Punt C, Ricke J, Roth A, Salazar R, Scheithauer W, Schmoll HJ, Tabernero J, Taïeb J, Tejpar S, Wasan H, Yoshino T, Zaanan A, Arnold D. ESMO consensus guidelines for the management of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1386–422.

Smyth EC, Verheij M, Allum W, Cunningham D, Cervantes A, Arnold D, ESMO Guidelines Committee. Gastric cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(suppl 5):v38–49.

Ducreux M, Cuhna AS, Caramella C, Hollebecque A, Burtin P, Goéré D, Seufferlein T, Haustermans K, Van Laethem JL, Conroy T, Arnold D, ESMO Guidelines Committee. Cancer of the pancreas: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(Suppl 5):v56–68.

Kopetz S, Chang GJ, Overman MJ, Eng C, Sargent DJ, Larson DW, Grothey A, Vauthey JN, Nagorney DM, McWilliams RR. Improved survival in metastatic colorectal cancer is associated with adoption of hepatic resection and improved chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3677–83.

Shibutani M, Maeda K, Nagahara H, Fukuoka F, Iseki Y, Matsutani S, Kashiwagi S, Tanaka H, Hirakawa K, Ohira M. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes predict the chemotherapeutic outcomes in patients with stage IV colorectal cancer. In Vivo. 2018;32:151–8.

Ogiya R, Niikura N, Kumaki N, Bianchini G, Kitano S, Iwamoto T, Hayashi N, Yokoyama K, Oshitanai R, Terao M, Morioka T, Tsuda B, Okamura T, Saito Y, Suzuki Y, Tokuda Y. Comparison of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes between primary and metastatic tumors in breast cancer patients. Cancer Sci. 2016;107:1730–5.

Dieci MV, Criscitiello C, Goubar A, Viale G, Conte P, Guarneri V, Ficarra G, Mathieu MC, Delaloge S, Curigliano G, Andre F. Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes on residual disease after primary chemotherapy for triple-negative breast cancer: a retrospective multicenter study. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:611–8.

Gupta A, Sharma A, von Boehmer L, Surace L, Knuth A, van den Broek M. Radiotherapy supports protective tumor-specific immunity. Oncoimmunology. 2012;1:1610–1.

Sobottka B, Pestalozzi B, Fink D, Moch H, Varga Z. Similar lymphocytic infiltration pattern in primary breast cancer and their corresponding distant metastases. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5:e1153208.

Acknowledgements

This research received no specific grants from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. We thank Brian Quinn who provided medical writing services on behalf of JMC, Ltd.

Funding

No funding was acquired for this study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MS and KM designed the study, performed the statistical analysis and draft the manuscript. HN, TF and SM collected the clinical data and revised the manuscript critically. SK, HT, KH and MO designed the study and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research conformed to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients were informed of the investigational nature of this study and provided their written informed consent. This retrospective study was approved by the ethics committee of Osaka City University (approval No.3853).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Shibutani, M., Maeda, K., Nagahara, H. et al. A comparison of the local immune status between the primary and metastatic tumor in colorectal cancer: a retrospective study. BMC Cancer 18, 371 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4276-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4276-y