Abstract

Background

In this prospective non-interventional study, the effectiveness and tolerability of erlotinib in elderly patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) after ≥1 platinum-based chemotherapy were assessed.

Methods

A total of 385 patients ≥65 years of age with advanced NSCLC receiving erlotinib were observed over 12 months. The primary endpoint was the 1-year overall survival (OS) rate.

Results

Patients were predominantly Caucasian (99.2%), a mean of 73 years old; 24.7% had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) ≥2. Most common tumor histologies were adenocarcinoma (64.9%) and squamous cell carcinoma (22.3%). Of 119 patients tested, 15.1% had an activating epidermal growth factor receptor gene (EGFR) mutation. The 1-year OS rate was 31% (95% CI 25–36) with a median OS of 7.1 months (95% CI 6.0–7.9). OS was significantly better in females than males (p = 0.0258) and in patients with an EGFR mutation compared to EGFR wild-type patients (p = 0.0004). OS was not affected by age (p = 0.3436) and ECOG PS (p = 0.5364). Patients with squamous NSCLC tended to live longer than patients with non-squamous EGFR wild-type tumors (median OS: 8.6 vs 5.5 months). Cough and dyspnea improved during the observation period. The erlotinib safety profile was comparable to that in previous studies with rash (45.2%) and diarrhea (22.6%) being the most frequently reported adverse events.

Conclusions

Erlotinib represents a suitable palliative treatment option in further therapy lines for elderly patients with advanced NSCLC. The results obtained under real-life conditions add to our understanding of the benefits and risks of erlotinib in routine clinical practice.

Trial registration

BfArM (https://www.bfarm.de; ML23023); ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01535729; 20 Feb 2012).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide [1]; about 85% of cases are diagnosed as non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [2]. The median age of NSCLC patients is 70 years and the disease is usually diagnosed in advanced stages, when curative surgery is no longer feasible [3]. In metastasized disease, first-line chemotherapy is often not successful and the 5-year survival rate is only 4.2% [3]. NSCLC is histologically classified into the major subtypes adenocarcinoma (~ 40%) [4, 5], squamous cell carcinoma (~ 30–40%) [6,7,8,9] and large cell carcinoma (~ 5–10%) [9]. Survival has improved for all subtypes in recent years, but the extent of improvement has been higher for adenocarcinoma than squamous tumors [10]. Recurring mutations have been reported in genes coding for epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFR) in 10–40% of adenocarcinomas [11,12,13], but these mutations are rare in squamous tumors [14]. EGFR mutations can lead to constitutive activation of anti-apoptotic and proliferation signaling pathways, which promote cancer progression [15].

EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) are the preferred first-line treatment for advanced NSCLC with EGFR mutations [16, 17], and the EGFR-TKI erlotinib (Roche Pharma, Tarceva®, Basel, Switzerland) is also approved in Europe for treatment of patients with EGFR wild-type tumors after failure of at least one prior chemotherapy regimen [18].

Treating NSCLC is challenging because of the advanced age of patients. As EGFR-TKI avoid the systemic side effects of traditional chemotherapy they might be more suitable for treating elderly patients [19]. A large phase-3 trial with erlotinib including 586 younger and 163 elderly patients demonstrated a similar survival and quality of life (QoL) in both age groups, although a somewhat higher toxicity in the elderly was observed [20]. Clinical studies examining the elderly population are limited and often firm conclusions cannot be drawn [21, 22]. In this study (ElderTac: erlotinib in routine clinical practice in elderly patients with NSCLC), we examined the effectiveness and tolerability of erlotinib in elderly NSCLC patients with progressive disease on ≥1 platinum-based chemotherapy in Germany.

Methods

Study design

ElderTac was a multicenter, non-comparative, non-interventional, single-arm surveillance study documenting erlotinib treatment during routine clinical practice in Germany between April 2011 and August 2014. The observation period was 12 months. Information was gathered during examinations by the physician at baseline and after 3, 6, 9, and 12 months.

This study was conducted in accordance with the German Medicines Act (AMG chapter 67, section 6). It was registered with the German Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (BfArM) and at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01535729). Regular monitoring of study documentation in every center was performed by AMS Advanced Medical Services GmbH, Mannheim, Germany.

Patients and treatment

Elderly patients (≥65 years) with advanced or metastatic UICC stage IV NSCLC, confirmed by histological analysis, were recruited. Histological and immunohistochemical analysis was used to distinguish different types of NSCLC. Patients were eligible if they had progressive disease on ≥1 platinum-based chemotherapy treatment. Erlotinib was prescribed to patients in accordance with the terms of the marketing authorization. Specific treatment and diagnostic procedures were at the discretion of the treating physician.

Outcome measurements

The main outcome parameter was the 1-year overall survival (OS) rate. In addition, OS, 1-year progression-free survival (PFS) rate, PFS, objective response rate (ORR), disease control rate (DCR), symptom control, and adverse events (AE) were assessed. The ORR was defined as the proportion of patients with at least a partial response. The DCR was defined as the complete response + partial response + stable disease. Response to treatment was assessed by the investigator using RECIST criteria (version 1.1). AEs were coded by the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) (version 15.1).

EGFR mutation status

As erlotinib is approved in Europe for second−/third-line therapy of metastatic NSCLC irrespective of EGFR mutation status [18], EGFR mutation testing was performed at the discretion of the participating centers. EGFR testing using sequencing strategies was done by certified molecular pathology departments collaborating with the individual study centers. Results were documented as: not tested, not available, EGFR activating mutation or wild-type.

Statistics

To accurately estimate the 1-year OS, 400 patients were considered necessary, assuming a survival rate of 33 ± 4.6%, and using a symmetric 95% confidence interval (CI, calculated using Greenwood’s standard error estimate). The survival rate was estimated to be 33% based on publications of four big international studies [23,24,25,26]. Other data were analyzed descriptively.

The effectiveness and safety for all patients who received ≥1 dose of erlotinib were analyzed. Continuous and categorical data were described as median (minimum, maximum) and frequencies/percentages, respectively.

Survival was analyzed by Kaplan Meier methodology and survival curves were compared using an unstratified log-rank test. Survival and response data were analyzed overall and in the following subgroups: age (65–69, 70–74, 75–79, ≥80 years or < 75 and ≥ 75 years), EGFR mutation (positive or wild type), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) (0, 1, ≥2) and gender. The influence of age, gender and EGFR mutation status on the OS was additionally investigated using Cox regression models (considering single and multiple factors). Post-hoc analysis was performed to compare younger with older patients (< 75 or ≥ 75 years) and non-squamous EGFR wild-type carcinoma with squamous carcinoma.

No correction for missing data was performed.

Results

Patients

In 102 centers, 465 patients were screened for eligibility. Eighty patients were excluded for the following reasons: no previous failed platinum-based chemotherapy (33), NSCLC UICC stage IV histology not confirmed (20), < 65 years old (11), erlotinib not administered (9), patient records unavailable (5), lack of informed consent (1) and screening failure (1). In total, 385 patients were included in the analysis. At 3 months, data were available for 380 patients (98.7%). This decreased to 159 patients (41.3%) at 6 months, 80 (20.8%) at 9 months, and 54 (14.0%) at 12 months. The main reason for discontinuation was disease progression (60% patients).

The patients’ baseline data are presented in Table 1. The median age was 72 years (range: 62–90 years). The most common tumor histology was adenocarcinoma (64.9%), followed by squamous cell carcinoma (22.3%), and large cell carcinoma (4.2%). EGFR mutation screening was performed in 31% of patients and 15.1% had a positive EGFR mutation status. Although EGFR mutation testing was mainly performed in patients with adenocarcinoma, other histological tumor types cannot be excluded. Thus, we refer to non-squamous EGFR wild-type carcinoma hereafter.

At baseline, 16.6% and 54.5% of patients had an ECOG PS of 0 or 1, respectively, while 24.7% had an ECOG PS ≥2. This did change slightly at the 3-month visit, where 9.1% and 35.6% had an ECOG PS of 0 or 1, respectively. The percentage of patients with an ECOG PS ≥3 was < 3% for the rest of the observation period. The majority of patients had concomitant diseases (86.2%). The main comorbid conditions were chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (33.0%), diabetes mellitus (21.6%), heart failure (8.1%), coronary heart disease/angina pectoris (14.0%), peripheral arterial occlusion disease (10.4%), and stroke (6.8%).

All patients had previously received chemotherapy, mainly based on carboplatin (72.5%) and/or cisplatin (32.2%) (Table 1). Six or more cycles of chemotherapy were completed in 43.3% of patients, and only one cycle was completed in 4.5% of patients. Radiotherapy had been previously administered to 35.8% of patients. Additionally, 24.9% of patients had received previous surgical treatment; 43.8% of these with curative intent.

Treatment

At baseline, 91.7% of patients received the recommended daily dose of 150 mg erlotinib. Erlotinib dose was modified during the study course as follows: 3/6 months: increased in 4/3 patients (1.1/1.9%), reduced in 32/11 patients (8.7/7.1%), interrupted in 20/10 patients (5.4/6.5%), and discontinued in 192/64 patients (35/41.6%) out of 368/154 remaining patients. The main reason for dose reduction was intolerance (3/6 months: 27/6 patients [7.3/3.9%]). The main reason for discontinuation was disease progression (3/6 months: 132/49 patients [35.8/31.8%]).

Effectiveness of erlotinib treatment in elderly patients

Treatment response

Six months after treatment onset in the overall population, 2 of the 127 patients evaluated (1.6%) had a complete response, 12 (9.4%) had a partial response and 55 (43.3%) had stable disease. In EGFR wild-type patients, 1 of the 22 evaluated (3.6%) had a complete response, 1 (3.6%) had a partial response and 9 (40.9%) had stable disease after six months. ORR and DCR at the 3-month and the 6-month visit and treatment responses stratified according to tumor histology are displayed in Table 2.

Survival

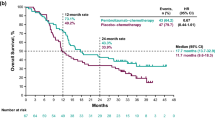

Overall, the 1-year OS rate was 31% (95% CI 25–36) with a median OS of 7.1 months (95% CI 6.0–7.9) (Table 2, Fig. 1a). The 1-year PFS rate and the median PFS were 19% (95% CI 15–23) and 3.5 months (95% CI 3.2–4.0), respectively.

Kaplan-Meier curves on 1-year overall survival in erlotinib-treated patients. a) Overall survival in the whole study population according to prespecified age group. b) Overall survival in patients with squamous carcinoma, patients with non-squamous EGFR wild-type carcinoma and patients with EGFR activating mutations. c) Overall survival according to age group (< 75 vs ≥75 years) in patients with squamous carcinoma and in patients with non-squamous EGFR wild-type carcinoma. CI, confidence interval; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor gene; HR, hazard ratio; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; OS, overall survival; WT, wild-type.

The OS curve was significantly affected by gender (p = 0.0258), demonstrating 1-year OS rates of 41.8% and 25.4% for females and males, respectively. The log-rank test additionally revealed a significant difference in the OS curves for the subgroup EGFR status (p = 0.0004, Fig. 1b). In contrast, OS curves were not significantly different between the four age groups (p = 0.3436) and the three ECOG PS groups (p = 0.5364) (Table 2). Cox regression models with adjustment for single factors showed a significant influence of gender (p = 0.027) and EGFR status (p = 0.001) on OS. Accordingly, females had an almost 30% reduced risk of death compared to males (hazard ratio [HR] 0.717, 95% CI 0.535–0.962). Patients with an EGFR mutation had an almost 80% reduced risk of death compared to wild-type patients (HR 0.211, 95% CI 0.083–0.539). In the Cox regression with adjustment for several parameters simultaneously, the association with reduced risk was maintained for positive EGFR mutation status (p = 0.002, HR 0.177, 95% CI 0.060–0.522). Age did not significantly influence the OS in either analysis (reference 65–74 years, p > 0.05).

Patients with squamous NSCLC tended to live longer (median OS: 8.6 months) than patients with documented non-squamous EGFR wild-type disease (median OS: 5.5 months) (Table 2; Fig. 1b, c). In addition, patients ≥75 years with non-squamous EGFR wild-type carcinoma had a tendency to live longer than their younger counterparts (median OS: 7.93 vs 5.16 months; p = 0.2895) (Fig. 1c).

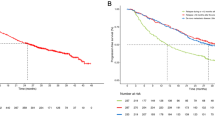

Symptom control

Symptoms were effectively managed during the observation period. At baseline, 41.6% of patients had cough and 44.4% dyspnea of predominantly mild to moderate intensity. Both symptoms improved at follow-up (Fig. 2). Based on the remaining patients under observation at each visit, only ≤2% of the patients had severe cough at each follow-up visit and severe dyspnea was observed in ≤6.45% of the patients during follow-up (Fig. 2). Post-hoc analysis of EGFR wild-type patients showed a similar symptom control compared to the overall population (data not shown).

Safety and tolerability of erlotinib treatment in elderly patients

During the study, 982 AEs were observed in 296 patients (76.9%) (Table 3). According to the common toxicity criteria for adverse events (CTC), 27.3% of patients had AEs of grade ≥ 3. Serious AEs were reported in 29.1% of patients that led to death in 13.0% of patients. The most commonly reported AEs were rash (45.2%) and diarrhea (22.6%), followed by dyspnea, fatigue, and cough. AEs led to permanent treatment discontinuation in 107 patients (27.8%): Main reasons were rash (26 patients, 6.8%), dyspnea (20 patients, 5.2%), and malignant neoplasm progression (17 patients, 4.4%). The frequency of AEs was not significantly affected by age or EGFR mutation status (data not shown). All AEs reported were consistent with those described in the summary of product characteristics [18].

Discussion

Few data regarding targeted cancer therapy in pretreated elderly NSCLC patients exist. Available study results in elderly patients with advanced NSCLC treated with erlotinib are summarized in Table 4.

In most studies, patients received erlotinib as first-line treatment [27,28,29] or the treatment line was not defined [30, 31]. Four studies included exclusively Asian patients [27, 31,32,33], who are known to have a better outcome with EGFR-TKI treatment compared to Caucasian patients [34]. In the phase-3 trial BR.21, involving 731 patients after progression on ≥1 platinum-based chemotherapy, erlotinib demonstrated prolonged survival [26] and improved QoL compared to placebo [35]. A retrospective subgroup analysis revealed that older (≥70 years) and younger patients had the same survival and QoL benefit, with a somewhat greater toxicity in the elderly [20]. However, the elderly population receiving erlotinib in that study (n = 112) [20] was small and a retrospective design involves a greater risk for bias compared with a prospective design.

The ElderTac study was designed to examine the effectiveness and tolerability of erlotinib as a second−/third-line treatment for advanced NSCLC in elderly patients in real life. In accordance with previous findings, females treated with erlotinib lived longer than males [36, 37]. The effectiveness of erlotinib in ElderTac was comparable with that in the BR.21 trial in which median OS/PFS durations of 7.6/3.0 months were observed in elderly patients receiving second- or third-line treatment with erlotinib [20]. Likewise, symptom control – as a surrogate for QoL – was improved in our population, confirming the results of the BR.21 trial [20, 26]. Maintenance of QoL is particularly important in patients with advanced disease receiving second- or third-line treatment. A recent clinical trial demonstrated a similar efficacy for erlotinib and chemotherapy as a second-line treatment for advanced NSCLC in unselected patients and the authors suggested that second-line treatment should be given on patient preference and individual toxicity-risk profiles [24]. However, this recommendation was based on a patient population with a median age of 59 years [24]. In our study, the median age was 72 years and a quarter of patients had an ECOG PS ≥2. Therefore, we have demonstrated that patients with a low performance status, who are not eligible for further chemotherapy, can still benefit from erlotinib. The tolerability of erlotinib in our study was consistent with previous clinical findings in elderly and non-elderly populations, with a tolerable toxicity profile and rash and diarrhea being the most frequently reported AEs [20, 26,27,28, 30, 38]. No new safety signals were observed. Erlotinib therefore represents a potential palliative treatment for elderly patients with advanced NSCLC.

Based on the mode of action, erlotinib is a more effective treatment for EGFR-mutated tumors. As expected, patients with an activating EGFR mutation had the greatest benefit from erlotinib treatment, in agreement with previous findings [28, 39]. Nonetheless, consistent with the results of two phase-3 trials [40], our response rates show that EGFR wild-type patients can also benefit from erlotinib treatment. A systematic review of the literature and metaanalysis revealed a significant improvement in OS with erlotinib versus other management options in patients with EGFR wild-type tumors [41]. In contrast, in the TAILOR and DELTA studies, chemotherapy with docetaxel was more effective than erlotinib for second- or third-line treatment of EGFR wild-type patients [42, 43]. However, the populations in TAILOR and DELTA are hardly comparable to the ElderTac population: Patients in TAILOR and DELTA were about six or five years younger and 92.7% or 96.0% of patients had an ECOG PS ≤1, respectively, compared to only 71.2% in ElderTac [42, 43]. Additionally, clinical parameters between the study cohorts in TAILOR were not balanced, as its original concept was not a comparison between erlotinib and docetaxel [42]. In the DELTA study, the subgroup analysis in the unselected population revealed no PFS benefit for docetaxel over erlotinib in patients ≥70 years of age [43], demonstrating that age is an important factor for the treatment decision.

Interestingly, erlotinib-treated patients with squamous tumors tended to live longer than patients with non-squamous EGFR wild-type carcinoma, which contradicts previous findings that the prognosis of adenocarcinoma patients is generally better than that of patients with squamous tumors [10]. The finding is unexpected considering the very low EGFR mutation rate in squamous tumors but may be explained by EGFR gene amplifications frequently found in these tumors [44, 45]. In a phase-4 trial in 1093 patients with metastastic squamous NSCLC, 95% of patients had tumors expressing detectable EGFR and 38% of tumors had a high EGFR expression as confirmed by immunohistochemistry [46]. The LUX-Lung 8 study revealed that the ErbB family blocker afatinib was superior to erlotinib in the treatment of squamous NSCLC [47]. However, the study exclusively included fit patients with an ECOG PS ≤1, and a statistically significant OS benefit for afatinib over erlotinib was only apparent in the subgroup of patients < 65 years of age (HR 0.68, 95% CI 0.55–0.85) but not in patients ≥65 years (HR 0.95, 95% CI 0.76–1.19) [47]. In contrast, our results demonstrate a benefit of erlotinib treatment in older patients (≥65 years) with squamous carcinoma, including unfit patients with an ECOG > 1. A recent case report of a 65-year-old man with EGFR-wildtype squamous lung cancer who had an unexpected prolonged response to third-line erlotinib confirms our results [48]. Because genomic alterations have not been comprehensively characterized in squamous tumors, no molecular-targeted therapies have been developed for this NSCLC type so far [45]. Meanwhile, immune checkpoint inhibitors are established first- and/or second-line treatments for NSCLC including squamous tumors [49,50,51,52], so that EGFR-TKI will likely move to further therapy lines in patients with squamous EGFR wild-type tumors.

A further unexpected result was that older patients with non-squamous EGFR wild-type carcinoma (≥75 years) tended to live longer than their younger counterparts. This finding is confirmed by results from a Japanese study with gefitinib in which an age < 75 years was an independent negative factor affecting PFS after EGFR-TKI therapy in patients with advanced NSCLC [53].

Most limitations of our study relate to the nature of a non-interventional trial, especially the lack of a control group and the open-label design. The low rate of EGFR mutation testing hampered the comparison of erlotinib effectiveness in a larger group of patients with or without EGFR mutations. It, however, reflects the clinical routine in Germany at the time the study was performed, with EGFR mutation analysis being done in less than 50% of NSCLC patients [54]. The high rate of treatment discontinuations due to the severely ill patient population might have had an influence on data analysis and interpretation. Furthermore, the results of post-hoc analyses have to be interpreted with caution. Nevertheless, our observational study generated invaluable results for real-life treatment decisions.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated that erlotinib is a suitable palliative treatment option in further therapy lines for elderly patients with recurrent/advanced NSCLC, especially in patients with an activating EGFR mutation and squamous histology. Our results were obtained under real-life conditions and therefore demonstrate effectiveness and tolerability of erlotinib in routine clinical practice.

Abbreviations

- AE:

-

Adverse event

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DCR:

-

Disease control rate

- ECOG PS:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status

- EGFR:

-

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- EGFR :

-

Epidermal growth factor receptor gene

- ElderTac:

-

Erlotinib in routine clinical practice in elderly patients with NSCLC

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- NSCLC:

-

Non-small-cell lung cancer

- ORR:

-

Objective response rate

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PFS:

-

Progression-free survival

- PS:

-

Performance state

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- TKI:

-

Tyrosine kinase inhibitor

References

Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87–108.

American Cancer Society: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/non-small-cell-lung-cancer/about/what-is-non-small-cell-lung-cancer.html. Accessed 19 Mar 2018.

SEER Cancer Statistics: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/lungb.html. Accessed 2 Dec 2015.

Travis WD. Pathology of lung cancer. Clin Chest Med. 2011;32(4):669–92.

Chang JS, Chen LT, Shan YS, Lin SF, Hsiao SY, Tsai CR, Yu SJ, Tsai HJ. Comprehensive analysis of the incidence and survival patterns of lung Cancer by Histologies, including rare subtypes, in the era of molecular medicine and targeted therapy: a nation-wide Cancer registry-based study from Taiwan. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(24):e969.

Jimenez Massa AE, Alonso Sardon M, Gomez Gomez FP. Lung cancer: how does it appear in our hospital? Rev Clin Esp. 2009;209(3):110–7.

Kukulj S, Popovic F, Budimir B, Drpa G, Serdarevic M, Polic-Vizintin M. Smoking behaviors and lung cancer epidemiology: a cohort study. Psychiatr Danub. 2014;26(Suppl 3):485–9.

Missaoui N, Hmissa S, Landolsi H, Korbi S, Joma W, Anjorin A, Ben Abdelkrim S, Beizig N, Mokni M. Lung cancer in Central Tunisia: epidemiology and clinicopathological features. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12(9):2305–9.

Novaes FT, Cataneo DC, Ruiz Junior RL, Defaveri J, Michelin OC, Cataneo AJ. Lung cancer: histology, staging, treatment and survival. J Bras Pneumol. 2008;34(8):595–600.

Olszewski AJ, Ali S, Witherby SM. Disparate survival trends in histologic subtypes of metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: a population-based analysis. Am J Cancer Res. 2015;5(7):2229–40.

Marchetti A, Martella C, Felicioni L, Barassi F, Salvatore S, Chella A, Camplese PP, Larussi T, Mucilli F, Mezzetti A, et al. EGFR mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer: analysis of a large series of cases and development of a rapid and sensitive method for diagnostic screening with potential implications on pharmacologic treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(4):857–65.

Sugio K, Uramoto H, Ono K, Oyama T, Hanagiri T, Sugaya M, Ichiki Y, So T, Nakata S, Morita M, et al. Mutations within the tyrosine kinase domain of EGFR gene specifically occur in lung adenocarcinoma patients with a low exposure of tobacco smoking. Br J Cancer. 2006;94(6):896–903.

Varghese AM, Sima CS, Chaft JE, Johnson ML, Riely GJ, Ladanyi M, Kris MG. Lungs don't forget: comparison of the KRAS and EGFR mutation profile and survival of collegiate smokers and never smokers with advanced lung cancers. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8(1):123–5.

Lopes GL, Vattimo EF, Castro Junior G. Identifying activating mutations in the EGFR gene: prognostic and therapeutic implications in non-small cell lung cancer. J Bras Pneumol. 2015;41(4):365–75.

Yarden Y, Sliwkowski MX. Untangling the ErbB signalling network. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2(2):127–37.

Novello S, Barlesi F, Califano R, Cufer T, Ekman S, Levra MG, Kerr K, Popat S, Reck M, Senan S, et al. Metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(suppl 5):v1–v27.

Brueckl WM. Treatment choice in EGFR-mutant non-small-cell lung cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30684-8. [Epub ahead of print]

Tarceva®. Summary of product characteristics. In: Last updated 12; 2017.

Gridelli C, Maione P, Rossi A, Ferrara ML, Castaldo V, Palazzolo G, Mazzeo N. Treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer in the elderly. Lung Cancer. 2009;66(3):282–6.

Wheatley-Price P, Ding K, Seymour L, Clark GM, Shepherd FA. Erlotinib for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer in the elderly: an analysis of the National Cancer Institute of Canada clinical trials group study BR.21. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(14):2350–7.

Lewis JH, Kilgore ML, Goldman DP, Trimble EL, Kaplan R, Montello MJ, Housman MG, Escarce JJ. Participation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(7):1383–9.

Vora N, Reckamp KL. Non-small cell lung cancer in the elderly: defining treatment options. Semin Oncol. 2008;35(6):590–6.

Karampeazis A, Voutsina A, Souglakos J, Kentepozidis N, Giassas S, Christofillakis C, Kotsakis A, Papakotoulas P, Rapti A, Agelidou M, et al. Pemetrexed versus erlotinib in pretreated patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a Hellenic oncology research group (HORG) randomized phase 3 study. Cancer. 2013;119(15):2754–64.

Ciuleanu T, Stelmakh L, Cicenas S, Miliauskas S, Grigorescu AC, Hillenbach C, Johannsdottir HK, Klughammer B, Gonzalez EE. Efficacy and safety of erlotinib versus chemotherapy in second-line treatment of patients with advanced, non-small-cell lung cancer with poor prognosis (TITAN): a randomised multicentre, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(3):300–8.

Reck M, van Zandwijk N, Gridelli C, Baliko Z, Rischin D, Allan S, Krzakowski M, Heigener D. Erlotinib in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: efficacy and safety findings of the global phase IV Tarceva lung Cancer survival treatment study. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5(10):1616–22.

Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, Tan EH, Hirsh V, Thongprasert S, Campos D, Maoleekoonpiroj S, Smylie M, Martins R, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(2):123–32.

Chen YM, Tsai CM, Fan WC, Shih JF, Liu SH, Wu CH, Chou TY, Lee YC, Perng RP, Whang-Peng J. Phase II randomized trial of erlotinib or vinorelbine in chemonaive, advanced, non-small cell lung cancer patients aged 70 years or older. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7(2):412–8.

Jackman DM, Yeap BY, Lindeman NI, Fidias P, Rabin MS, Temel J, Skarin AT, Meyerson M, Holmes AJ, Borras AM et al: Phase II clinical trial of chemotherapy-naive patients > or = 70 years of age treated with erlotinib for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2007, 25(7):760–766.

Merimsky O, Cheng CK, Au JS, von Pawel J, Reck M. Efficacy and safety of first-line erlotinib in elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Rep. 2012;28(2):721–7.

Stinchcombe TE, Peterman AH, Lee CB, Moore DT, Beaumont JL, Bradford DS, Bakri K, Taylor M, Crane JM, Schwartz G et al.: A randomized phase II trial of first-line treatment with gemcitabine, erlotinib, or gemcitabine and erlotinib in elderly patients (age >/=70 years) with stage IIIB/IV non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2011, 6(9):1569–1577.

Yoshioka H, Komuta K, Imamura F, Kudoh S, Seki A, Fukuoka M. Efficacy and safety of erlotinib in elderly patients in the phase IV POLARSTAR surveillance study of Japanese patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2014;86(2):201–6.

Yamada K, Azuma K, Takeshita M, Uchino J, Nishida C, Suetsugu T, Kondo A, Harada T, Eida H, Kishimoto J, et al. Phase II trial of Erlotinib in elderly patients with previously treated non-small cell lung Cancer: results of the lung oncology Group in Kyushu (LOGiK-0802). Anticancer Res. 2016;36(6):2881–7.

Miyawaki M, Naoki K, Yoda S, Nakayama S, Satomi R, Sato T, Ikemura S, Ohgino K, Ishioka K, Arai D, et al. Erlotinib as second- or third-line treatment in elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: Keio lung oncology group study 001 (KLOG001). Mol Clin Oncol. 2017;6(3):409–14.

Soo RA, Kawaguchi T, Loh M, Ou SH, Shieh MP, Cho BC, Mok TS, Soong R. Differences in outcome and toxicity between Asian and caucasian patients with lung cancer treated with systemic therapy. Future Oncol. 2012;8(4):451–62.

Bezjak A, Tu D, Seymour L, Clark G, Trajkovic A, Zukin M, Ayoub J, Lago S, de Albuquerque Ribeiro R, Gerogianni A, et al. Symptom improvement in lung cancer patients treated with erlotinib: quality of life analysis of the National Cancer Institute of Canada clinical trials group study BR.21. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(24):3831–7.

Cioffi P, Marotta V, Fanizza C, Giglioni A, Natoli C, Petrelli F, Grappasonni I. Effectiveness and response predictive factors of erlotinib in a non-small cell lung cancer unselected European population previously treated: a retrospective, observational, multicentric study. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2013;19(3):246–53.

Van Meerbeeck J, Galdermans D, Bustin F, De Vos L, Lechat I, Abraham I. Survival outcomes in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with erlotinib: expanded access programme data from Belgium (the TRUST study). Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2014;23(3):370–9.

Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, Vergnenegre A, Massuti B, Felip E, Palmero R, Garcia-Gomez R, Pallares C, Sanchez JM, et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(3):239–46.

Vale CL, Burdett S, Fisher DJ, Navani N, Parmar MK, Copas AJ, Tierney JF. Should Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Be Considered for Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients With Wild Type EGFR? Two Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Randomized Trials. Clin Lung Cancer. 2015;16(3):173–182.e174.

Osarogiagbon RU, Cappuzzo F, Ciuleanu T, Leon L, Klughammer B. Erlotinib therapy after initial platinum doublet therapy in patients with EGFR wild type non-small cell lung cancer: results of a combined patient-level analysis of the NCIC CTG BR.21 and SATURN trials. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4(4):465–74.

Jazieh AR, Al Sudairy R, Abu-Shraie N, Al Suwairi W, Ferwana M, Murad MH. Erlotinib in wild type epidermal growth factor receptor non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review. Ann Thorac Med. 2013;8(4):204–8.

Garassino MC, Martelli O, Broggini M, Farina G, Veronese S, Rulli E, Bianchi F, Bettini A, Longo F, Moscetti L, et al. Erlotinib versus docetaxel as second-line treatment of patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer and wild-type EGFR tumours (TAILOR): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(10):981–8.

Kawaguchi T, Ando M, Asami K, Okano Y, Fukuda M, Nakagawa H, Ibata H, Kozuki T, Endo T, Tamura A, et al. Randomized phase III trial of erlotinib versus docetaxel as second- or third-line therapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: docetaxel and Erlotinib lung Cancer trial (DELTA). J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(18):1902–8.

Hirsch FR, Varella-Garcia M, Bunn PA Jr, Di Maria MV, Veve R, Bremmes RM, Baron AE, Zeng C, Franklin WA. Epidermal growth factor receptor in non-small-cell lung carcinomas: correlation between gene copy number and protein expression and impact on prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(20):3798–807.

The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive genomic characterization of squamous cell lung cancers. Nature. 2012;489(7417):519–25.

Thatcher N, Hirsch FR, Luft AV, Szczesna A, Ciuleanu TE, Dediu M, Ramlau R, Galiulin RK, Balint B, Losonczy G, et al. Necitumumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin versus gemcitabine and cisplatin alone as first-line therapy in patients with stage IV squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (SQUIRE): an open-label, randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(7):763–74.

Soria JC, Felip E, Cobo M, Lu S, Syrigos K, Lee KH, Goker E, Georgoulias V, Li W, Isla D, et al. Afatinib versus erlotinib as second-line treatment of patients with advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the lung (LUX-lung 8): an open-label randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(8):897–907.

Gambale E, Carella C, Amerio P, Buttitta F, Patea RL, Natoli C, De Tursi M. Extraordinary and prolonged erlotinib-induced clinical response in a patient with EGFR wild-type squamous lung cancer in third-line therapy: a case report. Int Med Case Rep J. 2017;10:173–5.

Rittmeyer A, Barlesi F, Waterkamp D, Park K, Ciardiello F, von Pawel J, Gadgeel SM, Hida T, Kowalski DM, Dols MC, et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10066):255–65.

Reck M, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, Hui R, Csoszi T, Fulop A, Gottfried M, Peled N, Tafreshi A, Cuffe S, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive non-small-cell lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1823–33.

Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim DW, Felip E, Perez-Gracia JL, Han JY, Molina J, Kim JH, Arvis CD, Ahn MJ, et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10027):1540–50.

Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, Crino L, Eberhardt WE, Poddubskaya E, Antonia S, Pluzanski A, Vokes EE, Holgado E, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(2):123–35.

Masago K, Fujita S, Togashi Y, Kim YH, Hatachi Y, Fukuhara A, Nagai H, Sakamori Y, Mio T, Mishima M. Clinicopathologic factors affecting the progression-free survival of patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer after gefitinib therapy. Clin Lung Cancer. 2011;12(1):56–61.

Bertram M, Petersen V, Heßling J, Tessen HW, Münz M, Jänicke M, Spring L. N M: EGFR mutation testing and treatment with tyrosin-kinase inhibitors in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer treated by office based medical oncologists in Germany - data from the clinical registry on lung cancer (TLK). Oncol Res Treat. 2015;38(suppl 5):V886.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all patients and physicians who contributed to the study, which was sponsored by Roche Pharma AG, Grenzach-Wyhlen, Germany. Medical writing assistance was provided by Jutta Walstab, Physicians World Europe GmbH, Mannheim, Germany.

Funding

The study was funded by Roche Pharma AG, Grenzach-Wyhlen, Germany, who provided funding for data analysis and medical writing support.

Availability of data and materials

Study results are available on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01535729). Datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the study sponsor on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WMB, HJA, JHF and WS made substantial contributions to data acquisition, data interpretation and manuscript revision. WMB, HJA, JHF and WS gave final approval of the version to be published. The authors had complete access to the data that support this publication. WMB, HJA, JHF and WS agreed to be accountable for all content and editorial decisions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participating patients provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Friedrich-Alexander-Universitaet Erlangen-Nuernberg (no. 4441).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

WMB received lecture and consultancy fees from Astra Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, Lilly, MSD and Roche Pharma. JHF received lecture and consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche Pharma. WS declares receiving payments for lectures and consultancy from Roche Pharma. HJA received lecture and consultancy fees, as well as travel support from Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Grifols, Insmed, Lilly, Novartis, PneumRx, and Roche Pharma.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Brueckl, W.M., Achenbach, H.J., Ficker, J.H. et al. Erlotinib treatment after platinum-based therapy in elderly patients with non-small-cell lung cancer in routine clinical practice – results from the ElderTac study. BMC Cancer 18, 333 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4208-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4208-x