Abstract

Background

The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) are easily obtained from routine blood tests. We investigated the associations of the NLR and PLR with the clinical parameters and prognoses of small cell lung cancer (SCLC) patients.

Methods

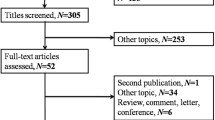

Pre-treatment clinical and laboratory data from 139 patients with SCLC were retrospectively studied with univariate analyses. The NLR and PLR values were divided into two separate groups: high NLR (>4.55, n = 32) vs low NLR (≤4.55, n = 107) and high PLR (>148, n = 63) vs low PLR (≤148, n = 76). Kaplan-Meier survival analyses and Cox proportional hazard models were used to examine the effects of NLR and PLR on overall survival.

Results

Chi-square analyses revealed significant associations of high NLR with tumour stage, hepatic metastasis, radiotherapy and chemotherapy and significant associations of high PLR with tumour stage, bone and hepatic metastases, exposure to cooking oil fumes, and chemotherapy. Mann-Whitney U tests demonstrated an association of high NLR with smoking exposure, and high NLR and high PLR were correlated with several laboratory parameters. Kaplan-Meier analyses revealed that high NLR and high PLR conferred poor prognoses for SCLC patients. Moreover, multivariate analysis demonstrated that NLR, tumour stage, and hepatic metastasis were independent prognostic factors for survival. In this study, we found that NLR and PLR were associated with several factors that reflect the inflammatory (white blood cell count, WBC; lactate dehydrogenase, LDH) and nutritional (albumin, ALB; haemoglobin, HB; and cholesterol) status of SCLC patients at diagnosis.

Conclusions

NLR is an independent prognostic factor and can be used to predict the mortality risk of SCLC patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide, and small cell lung cancer (SCLC) accounts for 15% of lung cancers. SCLC has the most aggressive clinical course of all pulmonary tumour types with a median survival from diagnosis of only 2 to 4 months without treatment [1]. Even with treatment, the median survival time for patients with limited stage SCLC is less than 24 months, and for those with extensive stage, the median survival is no more than 12 months [1, 2]. Several clinical markers are related to the prognoses of SCLC patients, including tumour stage, sex, serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and indicate a high tumour burden and a poor prognosis [3,4,5,6,7]. Albumin (ALB), haemoglobin (HB), and cholesterol (CHO), which reflect nutritional status, can also be of prognostic value [8,9,10]. However, the optimized prognostic factors for SCLC remains controversial [11]. Inflammation of the micro-environment plays a pivotal role in the development and progression of malignancies by influencing the proliferation and survival of tumour cells, promoting angiogenesis and metastasis, and reducing responses to anti-cancer agents [12]. Platelet activation is also stimulated by proinflammatory cytokines and participates in neutrophil recruitment [13]. Recent studies have focused on the relationships of inflammatory factors, the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) with survival in patients with various cancer types including SCLC [2, 11, 14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Meta-analyses results also highlighted the prognostic values of NLR and PLR in various solid tumours [22, 23]. This study aims to investigate the clinical significance of pre-treatment NLR and PLR values and their relationship with the overall survival of Chinese patients with SCLC.

Methods

Study populations

One hundred and thirty nine patients diagnosed with SCLC in the West China Hospital between January 2009 and October 2013 was retrospectively analysed. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the West China Hospital of Sichuan University. The diagnoses of SCLC were made pathologically with surgically resected specimens, bronchoscopic biopsies, or CT-guided needle lung biopsies. Blood samples were collected from patients according to the standard operating procedures at diagnosis. HB, mean corpuscular volume (MCV), red blood cell count (RBC), platelets (PLT), white blood cell count (WBC), neutrophil and lymphocyte counts were determined with XE-2100 and XE-5000 systems (Sysmex corporation, Kobe, Japan). Serum ALB, LDH, alkaline phosphates (ALP), CHO, triglycerides (TG), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and creatinine (CR) were determined with a cobas 8000 analyser (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Serum CEA, cytokeratin fragment antigen 21–1 (CYFRA21-1), and neuron-specific enolase (NSE) were determined with a cobas E601 system (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). The NLR was defined as the ratio of neutrophil the count to the lymphocyte count, and the PLR was defined as the ratio of the PLT to the lymphocyte count. ROC (receiver operating characteristic) curves were used to define the cutoff values for the NLR and PLR.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as the means ± the SDs or the medians (first quartile-third quartile). The Statistical Product and Service Solutions 17.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) for Windows was used to perform the statistics. Student’s t tests and Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare normally and non-normally distributed variables, respectively. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to draw the survival rate curves, and the log-rank test was used to compare the differences in the curves. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard models were used to evaluate the prognostic variables. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

This study included 139 SCLC patients with the average age of 58.4 years old. Among these patients, 107 were male, and 32 were female. At the time of diagnosis, 55 cases had limited disease (LD) stage, and 83 cases had extensive disease (ED) stage. Thirty-nine patients were non-smokers, and the other 100 were current or ex-smokers. The median NLR and PLR values were 3.13 and 132.7, respectively (Table 1).

NLR values and clinical parameters

As defined by the ROC curve analyses, patients with NLR values ≤4.55 (n = 107) and >4.55 (n = 32) were classified as the low NLR and high NLR groups, respectively. The clinical and laboratory data are presented in Table 2. The high NLR group patients exhibited more advanced tumour stages (p = 0.005), a higher hepatic metastatic rate (p = 0.020), a greater amount of smoking (p = 0.031), and lower frequencies of patients received radiotherapy (p = 0.041) and chemotherapy (p = 0.043). These patients also exhibited higher PLR (p = 0.000), PLT (p = 0.035), WBC (p = 0.001), neutrophil (p = 0.000), lymphocyte (p = 0.000), LDH (p = 0.001), CYFRA21-1 (p = 0.017), and NSE (p = 0.034) levels and lower levels of RBC (p = 0.002), HB (p = 0.001), ALB (p = 0.000), CHO (p = 0.000), HDL-C (p = 0.007), and LDL-C (p = 0.001).

PLR values and clinical parameters

Patients with PLR ≤148 (n = 76) and >148 (n = 63) were divided into the low PLR and high PLR groups, respectively. The clinical and laboratory data are presented in Table 3. The patients in the high PLR group exhibited more advanced tumour stages (p = 0.000), higher bone and hepatic metastases rates (p = 0.021 and p = 0.004), higher frequencies of exposure to cooking oil fumes (p = 0.022), and lower rates of patients received chemotherapy (p = 0.008). These patients also had higher NLR (p = 0.000), PLT (p = 0.000), and LDH (p = 0.023) levels and lower levels of RBC (p = 0.000), HB (p = 0.000), MCV (p = 0.012), neutrophil (p = 0.000), lymphocyte (p = 0.000), ALB (p = 0.000), CHO (p = 0.002), LDL-C (p = 0.003), and CR (p = 0.011).

NLR, PLR and prognosis

The overall survival times for the 139 SCLC patients were obtained by follow up study for at least 12 months. As illustrated in Fig. 1, patients in the high NLR and PLR groups exhibited worse prognoses than those with low NLR and PLR values. (log-rank tests: p = 0.000 and p = 0.004, respectively). When stratified by tumour stage, the high NLR patients in both the LD (n = 56) and ED (n = 83) stages exhibited shorter overall survival times (log-rank tests: p = 0.013 and p = 0.002, respectively; Fig. 2A-B). No significant differences were observed in the high PLR group when stratified by tumour stage (log-rank tests: p = 0.871 and p = 0.413, respectively; Fig. 2C-D, Table 4). NLR > 4.55, PLR > 148, ED stage, metastases, including liver and adrenal metastases, the lack of radio- or chemotherapy, low RBC, HB, ALB level and high serum LDH level conferred poor prognoses (all p < 0.05). When the variables that were identified as significant in the univariate analyses were incorporated as the co-variables in the multivariate analyses, the results demonstrated that high NLR, advanced tumour stage, and hepatic metastasis were independent factors for poor survival (hazard ratio = 2.093, 95% confidence interval 1.079–4.063, p = 0.029; hazard ratio = 2.692, 95% confidence interval 1.501–4.830, p = 0.001; and hazard ratio = 2.427, 95% confidence interval 1.341–4.395, p = 0.003; respectively, Table 4).

Discussion

Over the decades, the survival time of SCLC patients has not been prolonged with or without treatment. In this study, we reviewed the prognostic significance of NLR and PLR with clinical and laboratory markers in 139 SCLC patients. Our results revealed that high pre-treatment NLR and PLR values were associated with several clinical and laboratory markers. High NLR and PLR conferred poor overall prognoses on the SCLC patients. A high NLR value, ED stage, and hepatic metastasis were independent prognostic factors for poor outcomes in SCLC.

In our study, high pre-treatment NLR and PLR values were accompanied by an increased LDH level and decreased levels of several laboratory markers, including ALB, RBC, HB, and CHO. ALB is commonly used to represent the nutritional statuses of patients, and elevated serum ALB levels are associated with improved survival among lung cancer patients [24, 25]. HB, CHO, and LDH also exhibit significant prognostic values for lung cancer patients [7, 9, 10]. These previous findings are all consistent with our results (data not shown). Kaplan-Meier analyses demonstrated that high NLR and PLR confer poor overall survival time on patients. These findings could partly be explained by selection bias in that the patients in the high NLR and PLR groups also had high LDH and low HB, CHO, and ALB levels. However, the multivariate analyses revealed that NLR was an independent prognostic factor for poor outcomes in SCLC patients. Several studies have reported controversial results regarding the prognostic values of high NLR and PLR in terms of patient survival [2, 11, 26]. The selection of different cutoff values might have contributed to this controversy. However, in the study by Wang et al., elevated NLR was an independent prognostic factor for poor overall survival of SCLC patients in both the extensive and limited stages, which corroborated our results. In our study, we do not observe an independent prognostic value of PLR for the prediction of the clinical outcomes of SCLC patients, which is also consistent with their report [21]. The similar genetic backgrounds may explain the consistency of the prognostic value of NLR, although both studies had small sample sizes (n = 139 in our study and n = 153 in theirs). Selection bias also existed in that the high NLR group included more patients in the ED stage and more hepatic metastasis; thus, these patients had poorer prognoses. However, the multivariate analysis provided evidence that high NLR, ED stage and hepatic metastasis are independent prognostic factors for poor overall survival.

Tumour metastasis, including hepatic and adrenal metastases and the lack of chemotherapy or radiotherapy were associated with poor overall survival (Table 4). These findings are consistent with previous reports of SCLC patients with and without hepatic metastasis [21, 26, 27].

Pre-treatment NLR is an easily measurable parameter. However, several reports have employed different cutoff values when evaluating the prognostic value of NLR. Inflammation conditions and steroid treatments could be confounding factors [11]. Although several studies, including our own, have found NLR to be an independent prognostic factor for cancer survival [2, 11, 26], multi-centre research is still needed to verify the association of NLR with cancer survival.

Limitation

For the small sample size in current study, we only performed analyses to show the association between prognosis and NLR. Further validation test should be used to verify whether NLR could predict the prognosis in patients with SCLC.

Conclusions

High NLR and PLR confer poor prognostic values on SCLC patients. NLR is an independent prognostic factor and could be used to predict the mortality risks of SCLC patients.

Abbreviations

- ALB:

-

Albumin

- ALP:

-

Alkaline phosphates

- CEA:

-

Carcinoembryomic antigen

- CHO:

-

Cholesterol

- CR:

-

Creatinine

- ED:

-

Extensive disease.

- HB:

-

Haemoglobin

- LD:

-

Limited disease

- LDH:

-

Lactate dehydrogenase

- MCV:

-

Mean corpuscular volume

- NLR:

-

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

- NSE:

-

Neuron specific enolase

- PLR:

-

Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio

- PLT:

-

Platelet

- RBC:

-

Red blood cell

- SCLC:

-

Small cell lung cancer

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- WBC:

-

White blood cell

References

American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2014. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2014.

Hong X, Cui B, Wang M, Yang Z, Wang L, Systemic Immune-inflammation XQ. Index, based on platelet counts and Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio, is useful for predicting prognosis in small cell lung cancer. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2015;236(4):297–304.

Li J, Dai CH, Chen P, JN W, Bao QL, Qiu H, et al. Survival and prognostic factors in small cell lung cancer. Med Oncol. 2010;27(1):73–81.

Fizazi K, Cojean I, Pignon JP, Rixe O, Gatineau M, Hadef S, et al. Normal serum neuron specific enolase (NSE) value after the first cycle of chemotherapy: an early predictor of complete response and survival in patients with small cell lung carcinoma. Cancer. 1998;82(6):1049–55.

Gronowitz JS, Bergstrom R, Nou E, Pahlman S, Brodin O, Nilsson S, et al. Clinical and serologic markers of stage and prognosis in small cell lung cancer. A multivariate analysis. Cancer. 1990;66(4):722–32.

Buccheri G, Ferrigno D. Prognostic factors of small cell lung cancer. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2004;18(2):445–60.

Albain KS, Crowley JJ, LeBlanc M, Livingston RB. Determinants of improved outcome in small-cell lung cancer: an analysis of the 2,580-patient southwest oncology group data base. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8(9):1563–74.

Moon H, Roh JL, Lee SW, Kim SB, Choi SH, Nam SY, et al. Prognostic value of nutritional and hematologic markers in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma treated by chemoradiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2015;

Bremnes RM, Sundstrom S, Aasebo U, Kaasa S, Hatlevoll R, Aamdal S, et al. The value of prognostic factors in small cell lung cancer: results from a randomised multicenter study with minimum 5 year follow-up. Lung Cancer. 2003;39(3):303–13.

Li JR, Zhang Y, Zheng JL. Decreased pretreatment serum cholesterol level is related with poor prognosis in resectable non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(9):11877–83.

Kang MH, Go SI, Song HN, Lee A, Kim SH, Kang JH, et al. The prognostic impact of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients with small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;111(3):452–60.

Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454(7203):436–44.

Ghasemzadeh M, Hosseini E. Platelet-leukocyte crosstalk: linking proinflammatory responses to procoagulant state. Thromb Res. 2013;131(3):191–7.

Bagante F, Tran TB, Postlewait LM, Maithel SK, Wang TS, Evans DB, et al. Neutrophil-lymphocyte and platelet-lymphocyte ratio as predictors of disease specific survival after resection of adrenocortical carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2015;112(2):164–72.

Han LH, Jia YB, Song QX, Wang JB, Wang NN, Cheng YF. Prognostic significance of preoperative lymphocyte-monocyte ratio in patients with resectable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(6):2245–50.

Lee S, SY O, Kim SH, Lee JH, Kim MC, Kim KH, et al. Prognostic significance of neutrophil lymphocyte ratio and platelet lymphocyte ratio in advanced gastric cancer patients treated with FOLFOX chemotherapy. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:350.

Szkandera J, Gerger A, Liegl-Atzwanger B, Absenger G, Stotz M, Friesenbichler J, et al. The lymphocyte/monocyte ratio predicts poor clinical outcome and improves the predictive accuracy in patients with soft tissue sarcomas. Int J Cancer. 2014;135(2):362–70.

Stotz M, Gerger A, Eisner F, Szkandera J, Loibner H, Ress AL, et al. Increased neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio is a poor prognostic factor in patients with primary operable and inoperable pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;109(2):416–21.

Smith RA, Bosonnet L, Raraty M, Sutton R, Neoptolemos JP, Campbell F, et al. Preoperative platelet-lymphocyte ratio is an independent significant prognostic marker in resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg. 2009;197(4):466–72.

Kwon HC, Kim SH, Oh SY, Lee S, Lee JH, Choi HJ, et al. Clinical significance of preoperative neutrophil-lymphocyte versus platelet-lymphocyte ratio in patients with operable colorectal cancer. Biomarkers. 2012;17(3):216–22.

Wang X, Teng F, Kong L, Yu J. Pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a survival predictor for small-cell lung cancer. OncoTargets Therapy. 2016;9:5761–70.

Templeton AJ, Ace O, McNamara MG, Al-Mubarak M, Vera-Badillo FE, Hermanns T, et al. Prognostic role of platelet to lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2014;23(7):1204–12.

Templeton AJ, McNamara MG, Seruga B, Vera-Badillo FE, Aneja P, Ocana A, et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(6):dju124.

Gupta D, Lis CG. Pretreatment serum albumin as a predictor of cancer survival: a systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Nutr J. 2010;9:69.

Mori S, Usami N, Fukumoto K, Mizuno T, Kuroda H, Sakakura N, et al. The significance of the prognostic nutritional index in patients with completely Resected non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0136897.

Shao N, Cai Q. High pretreatment neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio predicts recurrence and poor prognosis for combined small cell lung cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2015;17(10):772–8.

He Y, Wang Y, Boyle T, Ren S, Chan D, Rivard C, et al. Hepatic metastases is associated with poor efficacy of Erlotinib as 2nd/3rd line therapy in patients with lung Adenocarcinoma. Med Sci Monitor. 2016;22:276–83.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledged the Medical Records Department for help collecting patients’ data.

Funding

This work was supported by the Sichuan Province Science and Technology Support Program (2014SZ0148, 2014SZ0126 and 2014SZ023) and the Nature Science Foundation of China (81201851). These four funding sources are all non-commercial research funds that were granted by the nation and province. The funding body had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Fund 2014SZ-148 was granted for the establishment of the lung cancer database. A portion of the clinical data used in this research was extracted from this database.

Funds 2014SZ0126 and 81,201,851 were used in obtaining the follow up data from this cohort of patients.

Fund 2014SZ023 was granted to research the role of exhaled breath condensate in the diagnosis of early lung cancer. In this manuscript, the NLR values of those diagnosed with lung cancer were collected and classified according to tumour stage.

Availability of data and materials

All data of from study are included in this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LD – acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript writing. HY – acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript writing. LL – acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data. SJ – acquisition of follow-up data. ZL – conception and design, interpretation of data, manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript. L-WM – conception and interpretation of data, manuscript writing, final approval of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved this manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by ethics committees of West China Hospital, Sichuan University (Ref no. 2017–114).

Written informed consent was obtained from the surviving patients during outpatient visits. Due to the retrospective nature of this study, some survival data were only obtained through telephone follow-ups because patients could not afford long journeys to reach the hospital. Only verbal informed consent was obtained from these patents or their legal guardians (for those passed away).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, D., Huang, Y., Li, L. et al. High neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios confer poor prognoses in patients with small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer 17, 882 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-017-3893-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-017-3893-1