Abstract

Background

Hypertensive crisis is an urgent/emergency condition. Although obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in resistant hypertension has been thoroughly examined, information regarding the risk factors and prevalence of hypertensive crisis in co-existing OSA and hypertension is limited. This study thus aimed to determine prevalence of and risk factors for hypertensive crisis in patients with hypertension caused by OSA.

Methods

The inclusion criteria were age of 18 years or over and diagnosis of co-existing OSA and hypertension. Those patients with other causes of secondary hypertension were excluded. Patients were categorized by occurrence of hypertensive crisis. Factors associated with hypertensive crisis were calculated using multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Results

There were 121 patients met the study criteria. Of those, 19 patients (15.70%) had history of hypertensive crisis. Those patients in hypertensive crisis group had significant higher systolic and diastolic blood pressure at regular follow-ups than those without hypertensive crisis patients (177 vs. 141 mmHg and 108 vs. 85 mmHg; p value < 0.001 for both factors). After adjusted for age, sex, and Mallampati classification, only systolic blood pressure was independently associated with hypertensive crisis with adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) of 1.046 (1.012, 1.080).

Conclusions

The prevalence of hypertensive crisis in co-existing OSA and hypertension was 15.70% and high systolic blood pressure or uncontrolled blood pressure associated with hypertensive crisis in patients with OSA-associated hypertension.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a disease that is commonly encountered in clinical practice. Its estimated prevalence is approximately 26% in the population between 30 and 70 years of age [1]. It causes intermittent desaturations during sleep, which can result in various cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, and stroke [2].

In 2003, OSA was found to be a common cause of hypertension [3]. The prevalence of OSA in hypertensive patients is approximately 50% and ranges from 30–80% [4]. The prevalence of OSA in patients with resistant hypertension is up to 71% which was similar to that in those with hypertensive crisis [5,6,7]. Large neck circumference, snoring, and age are predictors of OSA in these patients with adjusted odds ratios of 4.7 (1.3–16.9), 3.7 (1.3–11.0), and 5.2 (1.9–14.2), respectively [6]. However, although OSA in resistant hypertension has been thoroughly examined, information regarding the risk factors and prevalence of hypertensive crisis in co-existing OSA and hypertension is limited. This study thus aimed to determine prevalence of and risk factors for hypertensive crisis in patients with hypertension caused by OSA.

Methods

This was a retrospective study conducted at Khon Kaen University Hospital Hypertension clinic in Thailand. The inclusion criteria were age of 18 years or over and diagnosis of co-existing OSA and hypertension. The diagnosis of hypertension was based on the criteria proposed in the JNC 7 [3], while that of OSA was made according to the apnea-hyponea index (AHI; five or more apnea or hypopnea events per hour). Although hypertension can have various causes, this study examined only patients with hypertension caused by OSA and excluded all others. The study period was between 2015 and 2016.

We collected clinical data from the medical charts of all eligible patients recorded at the last follow-up including clinical features, symptoms and signs of OSA, co-morbid diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and laboratory investigation results. The outcome of this study was presence of hypertensive crisis at the Emergency Department, which was diagnosed as systolic and/or diastolic blood pressure greater than 180/110 mmHg [8]. Cases in which there was acute target organ damage from hypertensive crisis, such as heart failure or papilledema, were defined as hypertensive emergency, while those in which there was no acute target organ damage from hypertensive crisis were recorded as hypertensive urgency.

Sample size calculation. A previous report found the prevalence of hypertensive crisis in the Emergency Department to be 11.5% [9]. Based on a formula for a single population, we determined that the expected prevalence of hypertensive crisis in OSA patients was likely to be 20%. Thus, the required sample size was 77 to reach the expected OSA prevalence of 20% in hypertensive crisis with a confidence of 90% and power of 80%.

All eligible patients were classified by the presence of hypertensive crisis. Clinical factors of patients in both groups were compared using descriptive statistics. Factors associated with hypertensive crisis were calculated using logistic regression analysis. Univariate logistic regression analysis was used to identify the risk factors for hypertensive crisis. Those with p values less than 0.20 or clinically significant were included in the subsequent multivariate logistic regression analysis. Results of the logistic regression analyses were presented as unadjusted and adjusted odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). All analyses were performed using STATA version 10.1 (College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

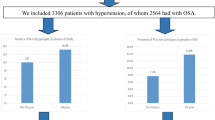

During the study period, there were 121 patients with hypertension caused by OSA. Of those, 19 (15.70%) had a history of hypertensive crisis, categorized as either hypertensive urgency (15 patients) or hypertensive emergency (four patients). There were two significant factors that differed between patients with and without history of hypertensive crisis (Table 1): systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Those with a history of hypertensive crisis had higher median systolic and diastolic blood pressure than those without (systolic: 177 vs. 141 mmHg; diastolic: 108 vs. 85 mmHg). Symptoms and signs of OSA, co-morbid diseases, and cardiovascular diseases were comparable between the two groups.

There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of laboratory results (Table 2). The hypertensive crisis group had a lower average apnea hypopnea index score than those without hypertensive crisis (14.5 vs. 19.5 events/hour; p value 0.363). After adjusting for age, sex, and Mallampati classification, only systolic blood pressure was independently associated with hypertensive crisis, with an adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) of 1.046 (1.012, 1.080).

Discussion

Hypertensive crisis (particularly hypertensive emergency) has been associated with high morbidity and mortality. A French study reported 15 deaths out of 46 patients (33%) within three months after admission with hypertensive emergency [10]. Previous studies have found the general prevalence of hypertensive crisis in hypertensive patients to be approximately 1–2%, of which 25% presented with hypertensive emergency [11, 12]. The population in this study was patients with hypertension caused by OSA. The prevalence of hypertensive crisis in this setting was much higher than in the general population (15.70% vs. 1–2%), but the proportion of patients with hypertensive emergency was comparable between this study and general population (21.1% vs. 25%) [11]. These results may indicate that patients with hypertension caused by OSA are at higher risk for hypertensive crisis. A previous study also confirmed this with evidence that OSA was a cause of hypertensive crisis in 70% of the161 patients examined [7].

One previous study in 89 hypertensive patients found female sex and obesity to be significantly associated with hypertensive crisis [13]. Our study found that in patients with co-existing OSA and hypertension, baseline systolic blood pressure was a significant risk factor for hypertensive crisis (Table 3). The median systolic blood pressure of the hypertensive crisis group was significantly higher than that of the non-hypertensive crisis group (177 vs. 141 mmHg), as shown in Table 1. We found similar results with regard to diastolic blood pressure. These findings were similar to those of a previous report from the US [14], which found that uncontrolled systolic blood pressure in an out-patient setting increased the risk of hypertensive crisis by 1.30 times. Note that the study population in the that report was not limited to OSA patients, as it was in this study.

Other OSA risk factors, such as age over 50 years, large neck circumference, and snoring, have been found to be significant predictors for OSA in cases of resistant hypertension (odds ratios of 5.2, 4.7, and 3.7, respectively) [6]. Our study found, however, that the correlations between these factors and hypertensive crisis in patients with hypertension caused by OSA were not statistically significant (Tables 1 and 3). These findings may be explained by the fact that this study only included patients with OSA, while the previous study included patients with all types of secondary hypertension.

There were some limitations in this study. First, the criteria for diagnosis of hypertensive crisis varies across studies [15]. In this study, we used those laid out in the GEAR project [8, 10, 16, 17], while some other studies have used diagnostic criteria such as systolic/diastolic blood pressure of 200/110 mmHg [3, 15]. However, had we used the latter definition, it would not have affected patient enrollment in this study. Numbers of eligible patients for both criteria were similar. Second, no causes/outcomes of hypertensive crisis or symptoms/signs preceding crisis were studied due to the retrospective study design. Therefore, OSA cannot be assumed to be the cause of hypertensive crisis. However, our aim was to determine the risk factors for hypertensive crisis in these patients, not to show a causal relationship between OSA and hypertensive crisis. Note that DBP was not included in the final model as it has collinearity with SBP, and there were few co-morbidities in the study population. Finally, this study was limited in that other aspects of OSA were not studied [18,19,20].

Conclusion

The prevalence of hypertensive crisis in patients with co-existing OSA and hypertension was 15.70%. High systolic blood pressure or uncontrolled blood pressure associated with hypertensive crisis in patients with OSA-associated hypertension.

Availability of data and materials

All relevant data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Garvey JF, Pengo MF, Drakatos P, et al. Epidemiological aspects of obstructive sleep apnea. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7(5):920–9.

Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, et al. European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: the Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts) Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2315–81.

Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–72.

Patel AR, Patel AR, Singh S, et al. The association of obstructive sleep apnea and hypertension. Cureus. 2019;11(6):e4858.

Martínez-García MA, Navarro-Soriano C, Torres G, et al. Hypertension. 2018;72(3):618–24.

Pedrosa RP, Drager LF, Gonzaga CC, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea: the most common secondary cause of hypertension associated with resistant hypertension. Hypertension. 2011;58:811–7.

Börgel J, Springer S, Ghafoor J, et al. Unrecognized secondary causes of hypertension in patients with hypertensive urgency/emergency: prevalence and co-prevalence. Clin Res Cardiol. 2010;99:499–506.

Salvetti M, Bertacchini F, Saccà G, Muiesan ML. Hypertension urgencies and emergencies: the GEAR project. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 2020;27:129–32.

Zampaglione B, Pascale C, Marchisio M, et al. Hypertensive urgencies and emergencies. Prevalence Clin Present Hypert. 1996;27:144–7.

Guiga H, Sarlon-Bartoli G, Silhol F, Radix W, Michelet P, Vaïsse B. Prevalence and severity of hypertensive emergencies and outbreaks in the hospital emergency department of CHU Timone at Marseille: follow-up in three months of hospitalized patients. Ann Cardiol Angeiol (Paris). 2016;65:185–90.

Pinna G, Pascale C, Fornengo P, et al. Hospital admissions for hypertensive crisis in the emergency departments: a large multicenter Italian study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93542.

Monnet X, Marik PE. What’s new with hypertensive crises? Intensive Care Med. 2015;41:127–30.

Saguner AM, Dür S, Perrig M, et al. Risk factors promoting hypertensive crises: evidence from a longitudinal study. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23:775–80.

Tisdale JE, Huang MB, Borzak S. Risk factors for hypertensive crisis: importance of out-patient blood pressure control. Fam Pract. 2004;21:420–4.

Cherney D, Straus S. Management of patients with hypertensive urgencies and emergencies: a systematic review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:937–45.

Patel KK, Young L, Howell EH, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients presenting with hypertensive urgency in the office setting. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:981–8.

Nakalema I, Kaddumukasa M, Nakibuuka J, Okello E, Sajatovic M, Katabira E. Prevalence, patterns and factors associated with hypertensive crises in Mulago hospital emergency department; a cross-sectional study. Afr Health Sci. 2019;19:1757–67.

Sawunyavisuth B. What are predictors for a continuous positive airway pressure machine purchasing in obstructive sleep apnea patients? Asia Pac J Sci Technol 2018;23:APST-23-03-10.

Phitsanuwong C, Ariyanuchitkul S, Chumjan S, Domthong A, Silaruks S, Senthong V. Does hypertensive crisis worsen the quality of life of hypertensive patients with OSA?: A pilot study. Asia Pac J Sci Technol 2017;22:APST-22-02-01.

Kingkaew N, Antadech T. Cardiovascular risk factors and 10-year CV risk scores in adults aged 30–70 years old in Amnat Charoen Province, Thailand. Asia Pac J Sci Technol 2019;24:APST-24-04-04.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Dylan Southard (USA) for his English language editing and the Khon Kaen University Sleep Apnea Research Group and Diamond project, Research Affair, Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand (DR64301).

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SK and KS designed the study and contributed significantly to manuscript preparation. SK, AC, PL, JC, WS, VC, SS, VS, and YS contributed to data collection, or data interpretation. BS and KS analysed data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Khon Kaen University Ethics Committee for Human Research (Thailand; HE541373). Written informed consent was not required due to retrospective data collection.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Khamsai, S., Chootrakool, A., Limpawattana, P. et al. Hypertensive crisis in patients with obstructive sleep apnea-induced hypertension. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 21, 310 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-021-02119-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-021-02119-x