Abstract

Background

Drought is by far the most important environmental factor contributing to yield losses in crops, including soybeans [Glycine max (L.) Merr.]. To address this problem, a gene that encodes an osmotin-like protein isolated from Solanum nigrum var. americanum (SnOLP) driven by the UBQ3 promoter from Arabidopsis thaliana was transferred into the soybean genome by particle bombardment.

Results

Two independently transformed soybean lines expressing SnOLP were produced. Segregation analyses indicated single-locus insertions for both lines. qPCR analysis suggested a single insertion of SnOLP in the genomes of both transgenic lines, but one copy of the hpt gene was inserted in the first line and two in the second line. Transgenic plants exhibited no remarkable phenotypic alterations in the seven analyzed generations. When subjected to water deficit, transgenic plants performed better than the control ones. Leaf physiological measurements revealed that transgenic soybean plants maintained higher leaf water potential at predawn, higher net CO2 assimilation rate, higher stomatal conductance and higher transpiration rate than non-transgenic plants. Grain production and 100-grain weight were affected by water supply. Decrease in grain productivity and 100-grain weight were observed for both transgenic and non-transgenic plants under water deficit; however, it was more pronounced for non-transgenic plants. Moreover, transgenic lines showed significantly higher 100-grain weight than non-transgenic plants under water shortage.

Conclusions

This is the first report showing that expression of SnOLP in transgenic soybeans improved physiological responses and yield components of plants when subjected to water deficit, highlighting the potential of this gene for biotechnological applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Soybean is one of the most important commodities in the world, and drought is one of the most relevant environmental factors contributing to yield losses. Long-term drought stress is a major problem, but in the short term, it also decreases crop production even when other conditions are favorable and may have serious economic and social consequences. In Brazil, the occurrence of prolonged drought during the soybean growing season has become increasingly common in recent years. This situation may become even more dramatic in light of current environmental change predictions, which point to global warming and the consequent occurrence of drought stress [1].

Molecular biology tools for the identification and transfer of genes responsible for drought tolerance have been applied to combat drought in soybean [1]. Different types of genetically modified plants have been developed to overcome water deficit, including the over expression of protective proteins.

Osmotins (osmotin-like proteins or OLPs) are members of the Pathogenesis-related protein 5 (PR-5) family [2], which are produced in plants under different abiotic and biotic stresses [3]-[6]. These proteins were identified in several plant species, including strawberry, Fragaria ananassa [6], Arabidopsis thaliana [7] and soybean, Glycine max [8],[9].

Numerous studies have been performed to determine the physiological role of osmotin in stress tolerance, but the mechanism of its action remains unclear. It has been reported that tobacco osmotin overexpression in different plant species confers tolerance to abiotic stresses, especially salinity and drought. This response was observed in transgenic plants of tobacco, Nicotiana tabacum [10], wheat, Triticum aestivum [11], cotton, Gossypium hirsutum [12], tomato, Solanum lycopersicum [13], and soybean [14]. Tobacco osmotin can act in osmotolerance by facilitating the compartmentalization of solutes [10] or metabolic/structural alterations during osmotic adjustment [3],[4].

The genus Solanum has a broad set of genes, including the PR-5 protein family, with the potential to confer resistance to pathogens [4]. Two PR5-like genes were isolated from the genome of black nightshade (Solanum nigrum L. var. americanum), a solanaceous weed. The predicted products of both genes, named SnOLP (neutral) and SnOSML (basic), showed a high homology with tobacco osmotin [15]. As have been shown that the expression of tobacco osmotin enhances salinity tolerance in transgenic soybean [14], our hypothesis was that drought tolerance could be achieved in soybean plants transformed with SnOLP due to crosstalk between these two abiotic stresses [13]. Thus, the objective of the present study was to investigate the usefulness of the SnOLP protein in developing transgenic soybean with enhanced drought tolerance. This is the first study to report that the SnOLP gene under the control of the UBQ3 promoter (UBQ3-P) from A. thaliana was transferred into the soybean genome. Our results showed an improvement of physiological responses when transgenic plants were subjected to water deficit.

Methods

Plant transformation

Embryogenic tissues induced from immature cotyledons of soybean cultivar Bragg were transformed by particle bombardment as described by Droste [16]. The pCL1390-UBQ3-SnOLP vector, a pCAMBIA1390 derivative (Cambia.org), contains the complete SnOLP gene ORF (GenBank accession AF450276) driven by the UBQ3 promoter (UBQ3-P) from A. thaliana and the hygromycin-phosphotransferase marker gene (hpt II) driven by the cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter (Figure 1).

Diagram of the T-DNA region of the binary vector pCL1390-UBQ3- Sn OLP. LB: T-DNA left border, RB: right border, T35S: Cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S terminator, hptII: hygromycin phosphotransferase gene, P35S: CaMV 35S promoter, UBQ3-P: Ubiquitin 3 promoter from A. thaliana, SnOLP: Solanum nigrum osmotin-encoding sequence, Tnos: nopaline synthase gene terminator.

Selection of hygromycin resistant embryogenic tissues, embryo histodifferentiation, conversion into plants and acclimation were carried out using the methodology previously described [16],[17].

Hygromycin-resistant embryogenic tissues were visually selected and separately cultured for establishment and proliferation of lines corresponding to putative independent transformation events. Thus, plants were recovered from three putative transformation events: B1, B2 and B3 lines. Plants derived from an independent piece of hygromycin-resistant tissue were noted as being clone plants.

Plants derived from non-transformed embryogenic tissues subjected to the same culture conditions were recovered and used as controls for molecular characterization.

PCR analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from all recovered putative transformed plants (B1, B2 and B3 lines) and from untransformed soybean plants using the CTAB method described by Doyle and Doyle [18]. PCR analyses were performed using specific primers for the SnOLP gene (PPS1-foward 5’-CGCGGATCCATGGGCTACTTGAGATCT-3’ and PCPT-reverse 5’-CCCAAGCTTTTACTTGGCCACTTCATC-3’ [15]), which amplify a 744-bp DNA fragment, and for the hptII gene (forward 5’-GCGATTGCTGATCCCCATGTGTAT-3’ and reverse 5’-GGTTTCCACTATCGGCGAGTACTT-3’), which amplify a 512-bp DNA fragment. The PCR reaction mixture consisted of 100 ng of template DNA, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1X Taq Buffer, 2 units of Taq® DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen), and 0.5 μM of each primer. Reactions were hot-started (3 min at 94°C) and subjected to 25 cycles as follows: 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 50°C and 2 min at 72°C with a final extension of 72°C for 5 min. All amplification reactions were carried out in a PCR Express Thermal Cycler (Thermo Hybaid, UK). PCR-amplified products were analyzed in 1% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide and visualized under UV light.

Protein expression analysis

For protein expression analysis, 0.2 g of fresh leaf tissue was excised from transgenic T0 plants and non-transgenic plants and homogenized in 500 μL of extraction buffer containing 50 mM of 1 M Tris–HCl (pH 6.8), 0.2% (w/v) polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP-40) and 1% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol. Samples were stirred for 30 min at 4°C and then clarified by centrifugation at 10,000 g. The protein content in the crude extract was determined by the Bradford method [19], using bovine serum albumin as standard. For each plant, approximately 50 μg of crude protein extract was subjected to 12% (w/v) sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The presence of the SnOLP protein was detected using polyclonal antibody specific for tobacco osmotin (kindly supplied by Dr. Bernard Fritig and Dr. Pierrette Geoffroy, Institut de Biologie Moléculaire des Plantes du C.N.R.S, France). The protein bands were visualized using the ECL Western Blot Detection and Analysis System (GE Healthcare). To disrupt less-specific interaction more stringent conditions were used by including detergent (0.1% Tween-20) in the wash solution.

Progeny analysis

T1 seeds obtained from self-fertilization of two T0 plants (one representative from B1 line and one from B3) were sown in pots containing soil and maintained in greenhouse. All T1 plants were screened for the presence of the SnOLP and hptII genes by PCR. Subsequent generations were obtained by self-fertilization of transgenic plants. Homozygous plants were detected in T3 generation by progeny tests and confirmed by PCR. Homozygous transgenic condition was monitored up to T7.

T5 homozygous transgenic plants were crossed, as pollen donors, with non-transgenic plants of BRS Fepagro 24 and BRS 211 soybean cultivars. SnOLP positive F1 plants obtained from crosses were self-fertilized to produce the F2 generation. F2 plants were screened for the presence of the SnOLP gene.

Transgene copy number estimation by quantitative Real Time PCR (qPCR)

One T5 homozygous plant from each B1 and B3 transgenic lines was assayed. Transgene copy number was estimated using relative quantification by qPCR standard curve analysis [20]. The curve was determined by the quantification of an endogenous gene in different DNA dilutions (1:100, 1:1,000 and 1:10,000). Lectin was chosen as the endogenous gene. Two lectin-encoding genes are present in soybean genome, this means there are four alleles in the homozygous diploid genome. The dilution 1:10,000 was hypothetically supposed to contain 4 alleles, the 1:1,000 40 alleles and 1:100 400 alleles. The copy number of transgenes in the same DNA dilutions was automatically calculated in proportion to that of the endogenous lectin genes using the StepOne Applied Biosystem Real-time Cycler™ (Quantification – standard curve experiment).

Primer pairs with a Tm at 60°C were designed to amplify gene sequences corresponding to SnOLP (forward 5’-CAACTTCGATGGTGCTGGTA-3’ and reverse 5’-TCA AAG CGT ATT CGG CTA GG-3’), hptII (forward 5’-TGGTTGGCTTGTATGGAGCAGCAG-3’ and reverse 5’-TGGTCAAGACCAATGCGGAGCATA-3’) and a lectin gene (forward 5’-TACCTATGATGCCTCCACCA-3’ and reverse 5’-GAGAACCCTATCCTCACCCA-3’).

qPCR was carried out under the following cycling conditions: 5 min at 94°C; followed by 40 repetitions of 10 s at 94°C, 15 s at 60°C and 15 s at 72°C; and 2 min at 40°C. A melting curve analysis was performed at the end of the PCR run, over the range 55-99°C, increasing the temperature stepwise by 0.1°C every 1 s. Each 25-μL reaction contained 12.5 μL diluted DNA template, 1x PCR buffer (Invitrogen, São Paulo, Brazil), 2.4 mM MgCl2, 0.024 mM dNTP, 0.1 μM each primer, 2.5 μL SYBR-Green (1:100.000, Molecular Probes Inc., Eugene, USA) and 0.3 U Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen, São Paulo, Brazil). PCRs were performed in technical quadruplicates, and no-template reactions were used as negative controls.

Plant growth, drought treatment and physiological analysis

A preliminary test was performed to analyze the behavior of transgenic soybean plants under drought conditions. Eight non-transgenic Bragg plants and eight T6 homozygous plants from each transgenic line (B1 and B3) were grown in 1-L plastic pots for 26 days in greenhouse. Plants were assessed for tolerance to water deficit stress by withholding irrigation for 10 days. Plants were monitored daily for wilting.

A second experiment was carried out to provide detailed characterization of physiological parameters in T7 transgenic plants subjected to drought stress. Plants were individually grown in PVC columns (100 cm in height and 35 cm in diameter) filled with turf and vermiculite (1:1 v/v), natural phosphate and macronutrients (Terral, TrueMix, Brazil). Plants were maintained in greenhouse at 28 ± 2°C and 60 ± 10% relative air humidity. Photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) was measured using a Quantum Sensor LI-COR (Q-45556) attached to a LI-COR 6400 (LICOR-6400, LI-COR Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA). The photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) varied from 647 to 1020 μmol m−2 s−1. The experiment was carried out with a completely randomized design using the two transgenic lines (B1 and B3) and the Bragg wild-type (WT) plants, under two water regimes (watered/always irrigated and stressed/with a water deficit imposed at beginning of pod formation – R3 stage) with five biological replicates. The experimental unit was one soybean plant grown in a PVC column.

Before sowing, the substrate was dried at 105°C. Each PVC column was filled with 43.0 kg of substrate. Six small holes were made in the column bottom to facilitate initial drainage. Subsequently, columns were irrigated with water up to saturation and covered with plastic bags, and excess water was allowed to drain out for 24 hours. Then, drainage holes were sealed, and columns were weighed for field capacity determination. Three seeds were sown per column, leaving one plant per column after thinning on the day 12 after sowing. Every two weeks, 0.5 L of half-strength “Hoagland” solution [21] was applied to each column. The plants were irrigated regularly with water to maintain the substrate at field capacity up to the R3 stage (46 days after emergence; beginning of pod formation). After that, plants were separated into two groups: one continued to receive regular irrigation (watered plants), and the other was subjected to water deficit (stressed plants).

Measurements of water potential were performed as described [22] using an Oregon Corvallis pressure chamber, 97330 (PMS Instrument Company, Albany, OR, USA). Leaves were collected from the upper portion of the middle third of each plant.

The net assimilation rate (Pn), stomatal conductance (gs), and the transpiration rate (E) were measured from 09:00 to 11:00 a.m. under artificial, saturating photosynthetic photon flux (PPF) (900 μmol m−2 s−1), using a portable photosynthesis system infrared gas analyzer (Li-cor 6400XTR, Nebraska, USA.). Measurements were recorded at one, six and twelve days after imposing water stress.

At harvest maturity, 100-grain weight and grain production per plant were determined in five plants of each transgenic line (B1 and B3) and five WT plants.

Statistical analyses

The segregation rates of the T1 progenies of transgenic soybean plants, as well as the segregation ratios in the F2 generation from crosses between T5 homozygous transgenic plants and non-transgenic plants of two commercial cultivars, were analyzed using the chi-square test to confirm the expected Mendelian segregation pattern of 3:1 (transgenic:non-transgenic plants).

Predawn leaf water potential, net CO2 assimilation rate, stomatal conductance, transpiration rate, grain production per plant and 100-grain weight of the transgenic plants grown under two water regimes were compared to those of non-transgenic ones grown in the same environmental conditions. Data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) and comparison of means was performed with Student’s t-test using SPSS Statistics software. Physiological parameters obtained for B1 and B3 lines were compared to those of WT-plants for each evaluation day and water regime.

Results and discussion

Twelve plants were recovered from three independent pieces of hygromycin-resistant embryogenic clusters. The three putative independent transformed lines were named B1, B2 and B3. Ten clonal plants derived from B1, and one plant derived from each of the B2 and B3 lines. The recovered plants reached maturity, flowered and set seeds.

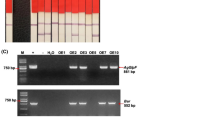

The stable integration of SnOLP and hptII transgenes into the genomes of hygromycin-resistant soybean plants was confirmed by PCR. Fragments with the expected size (512 bp for hptII and 744 bp for SnOLP) were detected in all plants from B1 as well as the plant from B3 lines (Figure 2). No PCR product for the tested gene was observed for the plant from B2 line, which was considered an “escape”. The expression of SnOLP was confirmed by Western blot. Using a polyclonal antibody against tobacco osmotin, a single band of approximately 27 kDa, corresponding to the SnOLP protein, was detected only in PCR-positive plants from B1 and B3 lines (Figure 2). No band was observed in non-transformed plants. Altogether, these data confirmed the successful production of soybean transgenic plants expressing the SnOLP gene.

Molecular analysis in transgenic soybean plants. PCR products of hptII and SnOLP genes amplified from DNA extracted from transgenic plants and controls. Detection of the SnOLP protein (~27 kDa) in soybean plants by Western blot hybridization. +: vector pCL1390-UBQ3-SnOLP (PCR positive control). B1, B2 and B3 lines: plants recovered from three putative transformation events. B1 line was represented by 10 clone plants. B2 and B3 lines were represented by one plant each. Two Bragg wild-type (WT) plants were used as negative controls.

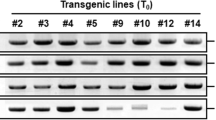

T1 progenies were used for transgene segregation analysis. Seeds harvested from one T0 plant representative of B1 and from the T0 plant from B3 lines were sowed, and T1 generation was analyzed by PCR. Both progenies segregated 3:1 for hptII and SnOLP transgenes (p > 0.05), indicating single locus insertions (Table 1). The transgene locus is considered to be hemizygous in the primary T0 transformant. Therefore, transgenes are generally expected to behave as dominant single genes and segregate in a 3:1 ratio when the plant is self-pollinated.

Homozygous plants were identified in the T3 generation. B1 and B3 homozygous transgenic lines were propagated up to T7 without the loss of transgenes. As predicted, crosses between homozygous transgenic plants and non-transformed plants of two commercial cultivars (Fepagro 24 and BRS 211) produced only hptII/SnOLP-positive F1 plants. The 3 transgenic:1 non-transgenic ratio (p > 0.05) observed in the F2 generation confirmed the Mendelian pattern for a single locus (Table 2).

The copy number of transgenes was calculated by qPCR proportionally to the endogenous lectin genes (Table 3). A single insertion of SnOLP was present in both the B1 and B3 lines. Differences between lines were detected for the hptII gene, i.e., one copy was inserted in B1 and two in B3. This result confirms that the transformed lines correspond to two independent transformation events. Transgenes rearrangements following particle bombardment have been widely reported [23],[24]. The insertion of one or a few transgene copies into the plant genome by particle bombardment is rare but has been previously reported in soybean [25].

Transgenic plants with a strong constitutive expression of functional genes often suffer from undesirable phenotypes including growth retardation, abnormal development, and reduced seed production. The plants obtained in the present study, in which the transgene is controlled by the constitutive UBQ3 promoter, did not show any remarkable phenotypic alteration on the course of the seven analyzed generations under regular watering regime.

Differences were observed between transgenic and control plants subjected to water deficit. The results of the preliminary test showed that transgenic plants of both lines (B1 and B3) performed better than the control ones. Results obtained from two out of eight plants/line are shown in Figure 3. After seven days without irrigation, non-transformed plants exhibited visible loss of turgidity, becoming limp and droopy. Transgenic plants appeared quite healthy up to 10 days without irrigation, when they started wilting (data not shown). Similarly, transgenic cotton and tomato plants overexpressing tobacco osmotin showed less severe wilting compared to controls [12],[13].

Plants under water deficit. Non-transgenic (WT) and transgenic plants expressing SnOLP after withholding water for seven days. Eight non-transgenic Bragg plants and eight T5 transgenic homozygous plants from each transgenic line (B1 and B3) were grown in 1-L plastic pots for 26 days in a greenhouse. Plants were assessed for tolerance to water deficit stress by withholding irrigation and were monitored daily for wilting.

In the second experiment, physiological parameters were evaluated under well-watered and drought stress conditions. The predawn leaf water potential (ΨPLWP) has been used as a tool to assess plant water status [26] because it integrates the effects of several drought-adaptive traits [27]. In our study, no difference was observed between transgenic and non-transgenic plants under regular irrigation (p > 0.05). Under water deficit, ΨPLWP was significantly lower in non-transgenic plants when compared to transgenic ones. The difference between transgenic and non-transgenic plants became evident after 6 days of water shortage (p < 0.01) (Figure 4A). This result indicates that plants overexpressing SnOLP are protected against dehydration.

Physiological evaluation of transgenic plants under water deficit. Predawn leaf water potential (A), net CO2 assimilation rate (B), stomatal conductance (C) and transpiration rate (D) of transgenic B1 and B3 lines and wild-type (WT) plants grown under two water regimes. Water deficit was imposed at R3 stage (beginning of pod formation). Measurements were recorded at one, six and twelve days after imposing water stress. Asterisks indicate significant differences of B1 or B3 lines compared to wild-type plants in each evaluation day and water regime (Student’s t-test, *: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01). Values are means ± SD (n = 5).

It has been shown that gas exchange variables in soybean are reduced by drought. Water deficit causes a decrease in photosynthetic rate by means of decreased stomatal conductance to carbon dioxide (CO2) as well as photosynthetic metabolic potential [28]. Under watered condition, net CO2 assimilation rate (Pn) was not significantly different in transgenic plants when compared to non-transgenic plants (p > 0.05) (Figure 4B). Pn decreased in all soybean plants under drought stress. However, Pn in transgenic plants was significantly higher than in wild-type plants at 12-day-drought stress (p < 0.01) (Figure 4B). This result indicates that soybean plants overexpressing SnOLP continue to assimilate CO2 even under drought stress.

The reduction in the photosynthetic rate is usually due to low stomatal conductance (gs), which reduces transpiration rate and internal CO2 concentration, leading to a decrease in plant development [29] and inhibition of photosynthesis [30]. Stomatal conductance (gs) was not significantly different in transgenic plants when compared to WT plants under watered conditions (Figure 4C). The gs values of all plants decreased during the drought period, but transgenic plants had significantly greater gs than those of the WT plants at 12 day-drought stress (p < 0.01). Plants with higher gs are desirable in soybean breeding strategies because low gs is related to decreased productivity [31].

Similarly, transpiration rate (E) did not differ in well-watered WT and transgenic plants (p > 0.05) (Figure 4D). During exposure to drought, transpiration increased in transgenic plants compared to WT ones. The transgenic plants of both lines showed significant differences in E (p < 0.01) starting on days 6 and 12 after stress was imposed.

Grain production and 100-grain weight were affected by water supply (Figure 5). For WT plants, grain productivity decreased approximately 20% when water shortage was imposed (Figure 5A). However, the reduction in grain production under drought stress for transgenic plants varied between 4.5% and 5.3% for B1 and B3 lines, respectively. The decrease in grain yield observed under water stress compared to watered conditions most likely occurred due to the loss of legumes since water stress was imposed at beginning of pod formation (R3 stage). Therefore, the reduction was more pronounced for WT plants than for transgenic ones, showing that transgenic plants were able to maintain higher growth rates compared to WT plants during water shortage.

Productivity of transgenic plants submitted to water deficit. Grain production per plant (A) and 100-grain weight (B) of transgenic B1 and B3 lines and wild-type (WT) plants grown under two water regimes. Water deficit was imposed for 12 days at R3 stage (beginning of pod formation). Asterisks indicate significant differences of B1 or B3 lines compared to wild-type plants in each water regime (Student’s t-test, p < 0.05). ns = non-significant difference. Values are means ± SD (n = 5).

Under watered conditions, grain production for the B1 line was significantly lower compared to WT plants (p < 0.05) (Figure 5A). In fact, there are reports demonstrating that transgenic plants carrying genes coding for osmoprotectants under a constitutive promoter may present morphological changes as well as growth rate and seed grain yield reduction [32],[33]. However, there is no sufficient basis to assume a negative association between osmotic adjustment and grain yield potential, especially considering the study carried out by Richardson and McCree [34], which demonstrated that the metabolic cost of storing photosynthate and using it for osmotic adjustment in sorghum was lower than the cost of converting it into shoot biomass.

Under watered conditions, 100-grain weight was similar for WT and transgenic plants (B1 and B3 lines) (p > 0.05) (Figure 5B). However, under water stress, 100-grain weight decreased approximately 12% for WT plants, while approximately 1.1% (B1) and 3.7% (B3) for transgenic plants. Moreover, plants from B1 and B3 lines exposed to water shortage showed higher 100-grain weights than WT plants (p < 0.05). The higher 100-grain weight observed for transgenic plants compared to WT plants may be explained by the effect of drought stress on net CO2 assimilation rate (Pn). As shown in Figure 4B, Pn in transgenic plants was significantly higher than in WT plants under water shortage. As discussed above higher CO2 assimilation increases grain-filling rate and duration as well as grain weight (Figure 5B).

Altogether our results indicate that transgenic soybean plants expressing SnOLP can sustain higher net CO2 assimilation, stomatal conductance, and transpiration compared to non-transformed plants. These data suggest that transgenic plants were able to better use internal carbon dioxide. Similar results were observed in soybean plants expressing an osmotin from tobacco when subjected to salinity stress [14].

Conclusions

The usefulness of the SnOLP protein in developing soybean transgenic plants with enhanced tolerance to drought has been demonstrated in this study. This biotechnological strategy combined with conventional genetic breeding approach should contribute to overcome the serious constraint – drought stress – for soybean production.

Availability of supporting data

Solanum nigrum osmotin-like protein precursor (OLP) gene, complete CDS (GenBank AF450276) - http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/AF450276.

Authors’ information

R.L.M. Weber – PhD, PostDoc, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil.

B.Wiebke-Strohm – PhD, PostDoc, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil.

C.Bredemeier – PhD, Professor, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil.

M.Margis-Pinheiro – PhD, Professor, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil.

G.G. de Brito – PhD, Researcher, Embrapa Clima Temperado, Brazil.

C.Rechenmacher – PhD student, Professor, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil.

P.F. Bertagnolli – PhD, Researcher, Embrapa Trigo, Brazil.

M.E.L. de Sá – PhD, Researcher, Empresa de Pesquisa Agropecuária de Minas Gerais and Embrapa Recursos Genéticos e Biotecnologia, Brazil.

M.A. Campos – PhD, Professor, Universidade Federal de Campina Grande, Brazil.

R.M.S. Amorim – PhD, PostDoc, Embrapa Recursos Genéticos e Biotecnologia, Brazil.

M.A. Beneventi – PhD, PostDoc, Embrapa Recursos Genéticos e Biotecnologia, Brazil.

R.Margis – PhD, Professor, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil.

M.F. Grossi-de-Sá – PhD, Researcher, Embrapa Recursos Genéticos e Biotecnologia, and Professor, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil.

M.H. Bodanese-Zanettini – PhD, Professor, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil.

References

Manavalan LP, Guttikonda SK, Tran LSP, Nguyen HT: Physiological and molecular approaches to improve drought resistance in soybean. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009, 50: 1260-1276. 10.1093/pcp/pcp082.

Van Loon LC, Van Strien EA: The families of pathogenesis-related proteins, their activities, and comparative analysis of PR-1 type proteins. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 1999, 55: 85-97. 10.1006/pmpp.1999.0213.

Singh NK, Bracker CA, Hasegawa PM, Handa AK, Buckel S, Hermodson MA, Pfankoch E, Regnier FE, Bressan RA: Characterization of osmotin: a thaumatin-like protein associated with osmotic adaptation in plant cells. Plant Physiol. 1987, 85: 529-536. 10.1104/pp.85.2.529.

Zhu B, Chen THH, Li PH: Activation of two osmotin-like protein genes by abiotic stimuli and fungal pathogen in transgenic potato plants. Plant Physiol. 1995, 108: 929-937. 10.1104/pp.108.3.929.

Gimeno J, Gadea J, Forment J, Pérez-Valle J, Santiago J, Martínez-Godoy MA, Yenush L, Bellés JM, Brumós J, Colmenero-Flores JM, Talón M, Serrano R: Shared and novel molecular responses of mandarin to drought. Plant Mol Biol. 2009, 70: 403-420. 10.1007/s11103-009-9481-2.

Zhang Y, Shih DS: Isolation of an osmotin-like protein gene from strawberry and analysis of the response of this gene to abiotic stresses. J Plant Physiol. 2006, 164: 68-77. 10.1016/j.jplph.2006.02.002.

Capelli N, Diogon T, Greppin H, Simon P: Isolation and characterization of a cDNA clone encoding an osmotin-like protein from Arabidopsis thaliana . Gene. 1997, 191: 51-56. 10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00029-2.

Onishi M, Tachi H, Kojima T, Shiraiwa M, Takahara H: Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel salt-inducible gene encoding an acidic isoform of PR-5 protein in soybean (Glycine max [L.] Merr.). Plant Physiol Biochem. 2006, 44: 574-580. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2006.09.009.

Tachi H, Fukuda-Yamada K, Kojima T, Shiraiwa M, Takahara H: Molecular characterization of a novel soybean gene encoding a neutral PR-5 protein induced by high-salt stress. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2009, 47: 73-79. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2008.09.012.

Barthakur S, Babu V, Bansal KC: Overexpression of osmotin induces proline accumulation and confers drought- and low-temperature stress tolerance in tobacco by gene transfer. Plant Cell Physiol. 2001, 45: 346-350.

Noori SAS, Sokhansanj A: Wheat plants containing an osmotin gene show enhanced ability to produce roots at high NaCl concentration. Russ J Plant Physiol. 2008, 55: 256-258. 10.1134/S1021443708020143.

Parkhi V, Kumar V, Sunilkumar G, Campbell LM, Singh NK, Rathore KS: Expression of apoplastically secreted tobacco osmotin in cotton confers drought tolerance. Mol Breed. 2009, 23: 625-639. 10.1007/s11032-009-9261-3.

Goel D, Singh AK, Yadav V, Babbar SB, Bansal KC: Overexpression of osmotin gene confers tolerance to salt and drought stresses in transgenic tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Protoplasma. 2010, 245: 133-141. 10.1007/s00709-010-0158-0.

Subramanyam K, Arun M, Mariashibu TS, Theboral J, Rajesh M, Singh NK, Manickavasagam M, Ganapathi A: Overexpression of tobacco osmotin (Tbosm) in soybean conferred resistance to salinity stress and fungal infections. Planta. 2012, 236: 1909-1925. 10.1007/s00425-012-1733-8.

Campos MA, Ribeiro SG, Rigden DJ, Monte DC, Grossi de Sá MF: Putative pathogenesis-related genes within Solanum nigrum L. var. americanum genome: isolation of two genes coding for PR5-like proteins phylogenetic and sequence analysis. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2002, 61: 205-216. 10.1006/pmpp.2002.0430.

Droste A, Pasquali G, Bodanese-Zanettini MH: Transgenic fertile plants of soybean [Glycine max (L) Merrill] obtained from bombarded embryogenic tissue. Euphytica. 2002, 127: 367-376. 10.1023/A:1020370913140.

Weber RLM, Körbes AP, Baldasso DA, Callegari-Jacques SM, Bodanese-Zanettini MH, Droste A: Beneficial effect of abscisic acid on soybean somatic embryo maturation and conversion into plants. Plant Cell Cult Micropropag. 2007, 3: 1-9.

Doyle JJ, Doyle JL: A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissues. Phytochem Bull. 1987, 19: 11-15.

Bradford MM: A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976, 72: 248-254. 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3.

Shou H, Frame BR, Whitham SA, Wang K: Assessment of transgenic maize events produced by particle bombardment or Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. Mol Breed. 2004, 13: 201-208. 10.1023/B:MOLB.0000018767.64586.53.

Hoagland DR, Arnon DI: The Water Culture Method for Growing Plants Without Soils. 1950, California Agricultural Experimental Station, Berkeley

Jordan WR, Ritchie JT: Influence of soil water stress on evaporation, root absorption, and internal water status of cotton. Plant Physiol. 1971, 48: 783-788. 10.1104/pp.48.6.783.

Kohli A, Twyman RM, Abranches R, Wegel E, Stoger E, Christou P: Transgene integration, organization and interaction in plants. Plant Mol Biol. 2003, 52: 247-258. 10.1023/A:1023941407376.

Gao C, Long D, Lenk I, Nielsen KK: Comparative analysis of transgenic tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea Schreb.) plants obtained by Agrobacterium-mediated transformation and particle bombardment. Plant Cell Reports. 2008, 27: 1601-1609. 10.1007/s00299-008-0578-x.

Hadi MZ, McMullen MD, Finer JJ: Transformation of 12 different plasmids into soybean via particle bombardment. Plant Cell Rep. 1996, 15: 500-505. 10.1007/BF00232982.

Williams LE, Araujo FJ: Correlations among predawn leaf, midday leaf, and midday stem water potential and their correlations with other measures of soil and plant water status in Vitis vinifera . J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 2002, 127: 448-454.

Mir RR, Zaman-Allah M, Sreenivasulu N, Trethowan R, Varshney RK: Integrated genomics, physiology and breeding approaches for improving drought tolerance in crops. Theor Appl Genet. 2012, 125: 625-645. 10.1007/s00122-012-1904-9.

Lawlor D, Tezara W: Causes of decreased photosynthetic rate and metabolic capacity in water-deficient leaf cells: a critical evaluation of mechanisms and integration of processes. Ann Bot. 2009, 103: 561-579. 10.1093/aob/mcn244.

Razzaghi F, Ahmadi SH, Adolf VI, Jesen CR, Jacobsen SE, Andersen MN: Water relations and transpiration of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) under salinity and soil drying. J Agro Crop Sci. 2011, 197: 348-360. 10.1111/j.1439-037X.2011.00473.x.

Bhargava S, Sawant K: Drought stress adaptation: metabolic adjustment and regulation of gene. Plant Breed. 2013, 132: 21-32. 10.1111/pbr.12004.

Gilbert ME, Zwieniecki MA, Holbrook NM: Independent variation in photosynthetic capacity and stomatal conductance leads to differences in intrinsic water use efficiency in 11 soybean genotypes before and during mild drought. J Exp Bot. 2011, 62: 2875-2887. 10.1093/jxb/erq461.

Tarczynski MC, Jensen RG, Bohnert HJ: Stress protection of transgenic tobacco by production of the osmolyte mannitol. Science. 1993, 259: 508-510. 10.1126/science.259.5094.508.

Romero C, Belles JM, Vaya JL, Serrano R, Culianez-Macia FA: Expression of the yeast trehalose-6-phosphate synthase gene in transgenic tobacco plants: pleiotropic phenotypes include drought tolerance. Planta. 1997, 201: 293-297. 10.1007/s004250050069.

Richardson SG, McCree KJ: Carbon balance and water relations of sorghum exposed to salt and water stress. Plant Physiol. 1985, 79: 1015-1020. 10.1104/pp.79.4.1015.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from the Brazilian Soybean Genome Consortium (Genosoja Project), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPQ), Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) and Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária (EMBRAPA).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Our team is composed of researchers from the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS) and Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária (EMBRAPA). Both are public institutions and the work was supported by Brazilian public funding agencies.

Authors’ contributions

RLMW participated in the study design, carried out the molecular biology studies and segregation analysis, and drafted the manuscript. BW-S participated in the molecular genetic studies and drafted the manuscript. CB performed statistical analysis, interpretation of physiological data and helped to draft the manuscript. MM-P participated in the study design. GGB carried out physiological assays. CR performed segregation and statistical analysis. PFB conceived and performed crosses. MELS designed physiological assays. MAC constructed the recombinant vector. RMSA participated on the design of physiological assays and molecular characterization. MAB participated on the design of physiological assays. RM carried out the molecular biology studies. MFG-S conceived of the study, participated in the study design and coordinated the EMBRAPA research group. MHB-Z conceived of the study, participated in its design, coordinated the UFRGS research group and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Weber, R.L.M., Wiebke-Strohm, B., Bredemeier, C. et al. Expression of an osmotin-like protein from Solanum nigrumconfers drought tolerance in transgenic soybean. BMC Plant Biol 14, 343 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-014-0343-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-014-0343-y