Abstract

Background

With the gaining popularity of commercially prepared decoctions of herbal medicines on the market, an objective and efficient way to reveal the authenticity of such products is urgently needed. Previous attempts to use chromatographic or spectroscopic methods to identify ginseng samples made use of components derived from methanol extracts of the herb. It was not established that these herbs can be distinguished solely from consumable components, which are responsible for the clinical efficacy of the herb.

In this study, metabonomics, or metabolic profiling, based on the application of 1H-Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), is applied to distinguish the water extracts of three closely related ginseng species: P. ginseng (from two different cultivated regions in China), P. notoginseng and P. quinquefolius.

Methods

A water extraction protocol that mimics how ginseng decoctions are made for consumption was used to prepare triplicate samples from each herb for analysis. High-resolution 1H NMR spectroscopy was used to acquire metabolic profiles of the four ginseng samples. The spectral data were subjected to multivariate and univariate analysis to identify metabolites that were able to distinguish different types of ginseng.

Results

H NMR metabolic profiling was performed to distinguish the water extracts of P. ginseng cultivated in Hebei and Jilin of China, both of which were distinguished from extracts of P. notoginseng and P. quinquefolius, by unsupervised principle component analysis based on the entire 1H NMR spectral fingerprint Statistically significant differences were found for several discriminating features traced to common metabolites and the ginsenosides Rg1 and Rd, in the 1H NMR spectra.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that 1H NMR metabonomics can simultaneously distinguish different ginseng species and multiple samples of the same species that were cultivated in different regions. This technique is applicable to the authentication and quality control of ginseng products.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The Panax L. (Araliaceae) genus consists of 12 species, including 10 from Asia and two from North America. Three species are commonly used today: Panax ginseng C.A. Mey., known as Ginseng, Renshen, or Korean Ginseng; Panax quinquefolius L., known as American Ginseng or Xiyangshen; and Panax notoginseng (Burk.) F.H. Chen, known as Notoginseng or Sanqi. While these Panax species have different clinical efficacies in Chinese medicine, they share a great deal of similarity in their chemistry and gene sequences, making their authentication difficult.

Currently, quality control of these three ginsengs is based on the relative quantities of saponins [1]. In addition, the ginsengs are graded and priced according to their origins, ages, and morphological characteristics [1], which are mainly determined after visual or microscopic inspection by experts [2]. However, this morphological method is subjective, and cannot be applied to medicinal products in the form of slices, powders, or decoctions.

Genetically, the three Panax species closely resemble one another. For example, P. ginseng, P. quinquefolius, and P. notoginseng have similar DNA sequences [3] for nuclear ribosomal DNA, 5S rRNA spacer, and 18S rRNA. Random amplified polymorphic analysis can distinguish the Panax species [4, 5], with restriction to the crude herbs instead of their extracts. Chemically, the important constituents of Panax roots, including ginsenosides Rb1, Rb2, Rd, Rg, and Re, are found in the roots of P. ginseng, P. quinquefolius, and P. notoginseng[6]. The presence of ginsenosides alone cannot offer conclusive evidence for species distinction. In 2006, Yang et al. [7] demonstrated the use of NMR metabonomics for quality control of commercial ginseng preparations. Similar metabonomic approaches were applied to distinguish the roots of P. ginseng and P. quinquefolius from different countries and ages by Kang et al. [8] and Lee et al.[1]. However, these previous attempts used methanol extraction, which is not typically used in ginseng preparation for consumption.

Therefore, this study aims to distinguish the Panax species roots from different cultivated regions in China and America in water extracts, that mimics the general way of ginseng consumption, to assess the potential of distinguishing ginseng decoctions by 1H NMR metabonomics.

Methods

Materials and reagents

All P. ginseng roots (Hebei-voucher# 10-5-23 and Jilin-voucher# 10-10-11) were obtained from their cultivated regions in China. P. quinquefolius roots (voucher# 10-8-12) were purchased from a local pharmacy and P. notoginseng roots (voucher# 10-9-26) were collected from Yunnan in China. The plant materials were collected in 2010, and authenticated by Dr. Tina T.X. Dong at Hong Kong University of Science & Technology according to their morphological characteristics [9]. The voucher specimens were deposited in the Centre for Chinese Medicine R&D at Hong Kong University of Science & Technology. All other reagents used in this study were of analytical grade (Sigma-Aldrich, USA).

Sample preparation

Ginsengs were prepared using the extraction procedure optimized by Song et al. [10]. Briefly, each sample (1 g) was cut into granules, boiled in 8 volumes of water (w/v) for 2 h, and extracted twice. The extracts were dried by lyophilization and stored at −40°C. Five biological replicates of each of the four herbs were prepared and analyzed in the same manner.

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)

The water extracts of different ginsengs were first analyzed by HPLC fingerprinting, according to a previously described method [11], to confirm the effectiveness of water extraction.

Sample preparation for NMR spectroscopy

Each extract (100 mg) was dissolved in 600 μL of sodium phosphate buffer (0.2 M Na2HPO4, 0.043 M NaH2PO4, 3 mM NaN3, 100% D2O, pH 7.4) with an internal standard, 0.1 mM sodium 3-(trimethylsilyl)propionate-2,2,3,3-d4 (TSP-d4). All particulate materials were removed by centrifugation (Prism, Labnet international, USA) at 13,000 x g for 1 min, and the supernatant was transferred to a standard 5-mm NMR tube. NMR spectra were acquired using a Bruker AV 400 MHz NMR spectrometer (Bruker Biospin, Rheinstetten, Germany) with a 5-mm PA BBO 400SB BBFO-H-D05 Z-gradient BB observe probe head, operating at 400.13 MHz 1H NMR frequency at 298 K. Gradient shimming was used to improve the magnetic field homogeneity prior to all acquisitions. 1H NMR spectra of the samples were acquired using a 1D NOESY pulse sequence (RD-90o-t1-90o-tm-90o-acquire) to generate a spectrum with a reduced residual solvent peak, 2-s relaxation delay, 100-ms mixing time, 20-ppm spectral width and 32000 acquired points. Each sample was run for 10 min. All spectra were Fourier-transformed, phase-corrected, and baseline-corrected manually.

Statistical analysis

All data were integrated using the rNMR program [12] and normalized by TSP-d4 as an internal standard. The data were formatted in XML for import into Matlab version 2009b, (MathWorks, USA) and SIMCA-P version 12.0 (Umetrics, Sweden). Each 1H-NMR spectrum was Pareto scaled and divided into 1.3-K bins (bin width, 0.0084 ppm). The summed intensity in each bin was used as a data point for principal component analysis (PCA). Metabolites were identified using Chenomx Profiler, a module of Chenomx NMR Suite version 7.5, online databases (hmdb.ca [13] & bmrb.wisc.edu [14]) and a previous report [15]. Differences between groups were performed by the Student’s t-test and subsequent Bonferroni correction of P values.

Results

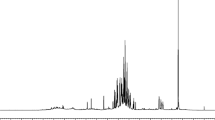

The water extracts of different ginsengs were first analyzed by HPLC fingerprinting, according to a previously described method [11], to confirm the effectiveness of water extraction. The average 1H spectra of the ginsengs from different origins, including P. quinquefolius from Wisconsin in the United States, P. ginseng from Hebei and Jilin in China, and P. notoginseng from Yunnan in China, were obtained (Additional file 1: Figure S1). By visual inspection, the average 1H NMR spectra of the four herbs showed similar, but also different characteristics.

The spectra were divided into data points and classified by PCA based on the sample origins. A PCA score plot, representing the relative position of each sample in the space of the principal components and maximizing the variance among all samples through linear combinations of sample features, revealed clusters of similar samples and individual samples with distinctive features (outliers). In this experiment, three principal components (PC1, PC2, and PC4) were required to conclusively classify all the spectra of the sample origins (Figure 1).

Chemometric analysis by a 3D score plot of the PCA. A score plot from pattern recognition (PCA) of the spectra is shown. The data sets are Pareto scaled. Overall, the plot can successfully distinguish the four groups of ginseng (N = 5). (PC1: R2 = 0.48, Q2 = 0.42; PC2: R2 = 0.71, Q2 = 0.59; PC4: R2 = 0.86, Q2 = 0.73).

Several regions of interest were isolated from the 1H-NMR spectra that distinguishd the herb origins, and were evaluated by Student’s t-tests on the differences in the metabolite concentrations between the herbs. A PCA loading plot (Additional file 2: Figure S2) showed that 3.4–4 ppm, a region associated with carbohydrates and sugars, had the most significant differences. The characteristic peaks associated with all metabolites were integrated (Figure 2, Additional file 3: Table S1), and showed that no metabolites could individually differentiate all ginsengs. Sucrose (5.42 ppm) was able to differentiate most of the ginsengs significantly, except for P. quinquefolius and P. ginseng (Hebei), and P. notoginseng and P. ginseng (Jilin).

Quantification of identified metabolites in the different ginseng extracts. The peaks associated with identified metabolites in all of the 1H-NMR spectra were integrated to yield measures of the concentrations in the extracts relative to the mean value for P. notoginseng (basal level). The values are expressed as means ± SD (N = 5). *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, by Student’s t-test (P values are Bonferroni-corrected for multiple testing.). Abbreviations: Q, P. quinquefolius; H, P. ginseng (Hebei); N, P. notoginseng; J, P. ginseng (Jilin).

Ginsenosides are the most important classes of compounds for the therapeutic effects of ginsengs, and are often used as chemical markers for quality control of ginsengs [6] The 1H NMR spectra of two major ginsenosides, Rg1 and Rd, were obtained (Additional file 4: Figure S3) and a well-resolved peak at 3.58 ppm, a location free from interfering signals from other identified metabolites in the ginseng water extract spectra, was identified (Figure 3A). All spectra exhibited a clearly resolved peak at 3.58 ppm. By assuming that the peak at 3.58 ppm arose from ginsenosides Rg1 or Rd and coincidentally from another unknown metabolite, we estimated that P. notoginseng contained a significantly higher amount of the ginsenoside than the other three ginsengs (Figure 3). However, the other three ginsengs were unable to be separated by the intensity of this peak, suggesting that the Rg1 and Rd concentration alone was insufficient to identify all the ginsengs.

Quantification of the ginsenoside peak at 3.358 ppm from different ginseng extracts. (A) 1H NMR spectra of ginsenosides showing the resonance of Rg1 (solid) and Rd (broken line). (B) The ginsenoside peak at 3.358 ppm was integrated to yield the measurements of the ginsenoside concentrations in the extracts relative to the mean value of P. notoginseng (basal level). The values are expressed as means ± SD (N = 5). *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, by Student’s t-test (P values are Bonferroni-corrected for multiple testing.).

Discussion

This study differed from previous ginseng studies that used methanol as an extraction solvent [1, 8]. The bioavailable chemicals of the four ginseng samples were directly observed by a water extraction protocol that resembles the commercial preparation of ginseng decoctions. Different extraction methods produce different quantities of metabolites. For example, comparing our metabolic profiles with those of Lee et al. [1], fewer metabolites were detected in the aromatic region (6–8 ppm). Our findings showed that P. quinquefolius had a significantly higher fructose concentration than P. ginseng, while Lee et al.[1] did not detect any significant difference. Our data also showed similar (in the case of Hubei-grown P. ginseng) or lower (in the case of Jilin-grown P. ginseng) concentrations in P. quinquefolius compared with P. ginseng, while Lee et al.[1] showed the opposite trend of much higher concentration of fumarate in P. quinquefolius than P. ginseng. Use of methanol extraction may not allow a direct demonstration of the chemical differences in the human-consumed components of these ginseng herbs.

The metabolite profiles from the 1H NMR spectra exhibited differences in the finer details for closely related ginseng species, and allowed measurements of different metabolites in an unbiased manner without prior chemical markers. The 1H NMR signal is directly proportional to the number of protons present, and the characteristic chemical shifts can identify and quantify many well-known metabolites, including amino acids, sugars, nucleotides, and other aromatic compounds [1]. In addition, the entire 1H-NMR spectrum can function as a fingerprint based on the content of metabolites from a biological sample, representing a valuable alternative to traditional methods in the absence of reliable chemical markers. PCA was used to identify differences in the 1H NMR spectra in an automated manner. When the group labels are unknown to the regression, this method is useful for outlier detection and detecting patterns and trends without prior knowledge. In this study, the four herbs were distinguished at once by the PCA, suggesting that this demonstration of the distinguishability may be more powerful than those in previous studies using supervised methods, such as Kang et al. [16] and Lee et al.[1].

No single metabolite was able to act as a biomarker for the classification of all four herbs. For example, fructose (4.21 ppm) was significantly different in P. quinquefolius, and can only be a potential biomarker for identifying P. quinquefolius but not the others, while sucrose (5.42 ppm) was able to differentiate most of the ginsengs significantly, but not P. quinquefolius and P. ginseng (Hebei), or P. notoginseng and P. ginseng (Jilin). These findings corroborate the findings from the PCA loading plot that the sugar region (3.4–4 ppm) is greatly discriminative. It is noted that choline was able to differentiate P. quinquefolius and P. ginseng (Hebei), and P. notoginseng and P. ginseng (Jilin). Taken together, choline and sucrose were able to distinguish the four ginsengs. A profiling approach can detect effective combinations of biomarkers automatically using ubiquitous metabolites.

To compare with the traditional method of discriminating samples based on known chemical markers, we attempted to identify peaks in the 1H NMR spectra that could correspond to two known ginsenosides. The 1H NMR spectra showed that P. notoginseng had a significantly higher amount of these ginsenosides than the other three herbs, consistent with a previous study [17]. In addition, the other three herbs were unable to be distinguished by this ginsenoside peak alone.

In this approach, the overall spectral fingerprint incorporating multiple markers, many of which have not previously been studied, was utilized successfully to distinguish the samples, in contrast to the traditional approach of relying on one or several known chemical markers. In contrast to previous work relying on different metabolite profiles obtained by methanol extraction, the water extraction used in the present study resembles that for commercial ginseng preparations.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that 1H NMR metabonomics can simultaneously distinguish different ginseng species and multiple samples of the same species cultivated in different regions. This technique is applicable to the authentication and quality control of ginseng decoctions.

Abbreviations

- PCA:

-

Principle component analysis

- TSP-d4:

-

Sodium 3-(trimethylsilyl)propionate-2,2,3,3-d4.

References

Lee EJ, Shaykhutdinov R, Weljie AM, Vogel HJ, Facchini PJ, Park SU, Kim YK, Yang TJ: Quality assessment of ginseng by H-1 NMR metabolite fingerprinting and profiling analysis. J Agric Food Chem. 2009, 57: 7513-7522. 10.1021/jf901675y.

Woo SH, Choi BC, Oh SJ, Seul JH: Classification of the first web space free flap of the foot and its applications in reconstruction of the hand. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999, 103: 508-517. 10.1097/00006534-199902000-00022.

Ngan F, Shaw P, But P, Wang J: Molecular authentication of Panax species. Phytochemistry. 1999, 50: 787-791. 10.1016/S0031-9422(98)00606-2.

Shaw PC, But PPH: Authentication of Panax species and their adulterants by random-primed polymerase chain-reaction. Planta Med. 1995, 61: 466-469. 10.1055/s-2006-958138.

Ha WY, Yau FCF, But PPH, Wang J, Shaw PC: Direct amplification of length polymorphism analysis differentiates Panax ginseng from P. quinquefolius. Planta Med. 2001, 67: 587-589. 10.1055/s-2001-16483.

Leung KSY, Chan K, Bensoussan A, Munroe MJ: Application of atmospheric pressure chemical ionisation mass spectrometry in the identification and differentiation of Panax species. Phytochem Anal. 1997, 18: 146-150.

Yang SY, Kim HK, Lefeber AW, Erkelens C, Angelova N, Choi YH, Verpoorte R: Application of two-dimensional nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy to quality control of ginseng commercial products. Planta Med. 2006, 72: 364-369. 10.1055/s-2005-916240.

Kang J, Lee S, Kang S, Kwon HN, Park JH, Kwon SW, Park S: NMR-based metabolomics approach for the differentiation of ginseng (Panax ginseng) roots from different origins. Arch Pharm Res. 2008, 31: 330-336. 10.1007/s12272-001-1160-2.

Department of Health government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, People’s Republic of china: Hong Kong Chinese Material Medica Standards Volume 1. 2005, China: Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

Song ZH, Ji ZN, Lo CK, Dong TT, Zhao KJ, Li OT, Haines CJ, Kung SD, Tsim KW: Chemical and biological assessment of a traditional Chinese herbal decoction prepared from radix astragali and radix angelicae sinensis: orthogonal array design to optimize the extraction of chemical constituents. Planta Med. 2004, 70: 1222-1227. 10.1055/s-2004-835855.

Li W, Fitzloff JF: Determination of 24(R)-pseudoginsenoside F(11) in north American ginseng using high performance liquid chromatography with evaporative light scattering detection. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2001, 25: 257-265. 10.1016/S0731-7085(00)00494-5.

Lewis IA, Schommer SC, Markley JL: rNMR: open source software for identifying and quantifying metabolites in NMR spectra. Magn Reson Chem. 2009, 47 (1): S123-S126. 10.1002/mrc.2526.

Wishart DS, Tzur D, Knox C, Eisner R, Guo AC, Young N, Cheng D, Jewell K, Arndt D, Sawhney S, Fung C, Nikolai L, Lewis M, Coutouly MA, Forsythe I, Tang P, Shrivastava S, Jeroncic K, Stothard P, Amegbey G, Block D, Hau DD, Wagner J, Miniaci J, Clements M, Gebremedhin M, Guo N, Zhang Y, Duggan GE, Macinnis GD, Weljie AM, Dowlatabadi R, Bamforth F, Clive D, Greiner R, Li L, Marrie T, Sykes BD, Vogel HJ, Querengesser L: HMDB: the human metabolome database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35: D521-D526. 10.1093/nar/gkl923.

Ulrich EL, Akutsu H, Doreleijers JF, Harano Y, Ioannidis YE, Lin J, Livny M, Mading S, Maziuk D, Miller Z, Nakatani E, Schulte CF, Tolmie DE, Kent Wenger R, Yao H, Markley JL: BioMagResBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36: D402-D408.

Fan WMT: Metabolite profiling by one- and two-dimensional NMR analysis of complex mixtures. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 1996, 28: 161-219.

Kang J, Choi M, Kang S, Kwon H, Wen H, Lee CH, Park M, Wiklund S, Kim HJ, Kwon SW, Park S: Application of a H-1 nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) metabolomics approach combined with orthogonal projections to latent structure-discriminant analysis as an efficient tool for discriminating between Korean and Chinese herbal medicines. J Agric Food Chem. 2008, 56: 11589-11595. 10.1021/jf802088a.

Dong TTX, Cui XM, Song ZH, Zhao KJ, Ji ZN, Lo CK, Tsim KWK: Chemical assessment of roots of Panax notoginseng in China: regional and seasonal variations in its active constituents. J Agric Food Chem. 2003, 51: 4617-4623. 10.1021/jf034229k.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Kai Qi Yan for HPLC quality assurance of the water extraction of the ginsengs, Chi Yuen Cheung for assistance with plotting of the figures and the Department of Chemistry, Hong Kong University of Science and Techonology, for providing the NMR machine for data generation. This research was supported by the University Grant Council of Hong Kong (HKUST RPC10EG08 to H. Lam), the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong (N_HKUST629/07, 662608 to K. Tsim), and the Croucher Foundation (CAS-CF07/08.SC03 to K. Tsim).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests

Authors’ contributions

KWKT, HL and PHC conceived the study and designed the experiments. PHC and KZYZ conducted the experiments. PHC wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

13020_2012_166_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Average 1H NMR spectra of the four ginseng extracts, P. quinquefolius, P. ginseng of Hebei, P. notoginseng, and P. ginseng of Jilin. The spectra represent the means of five replicates. By visual inspection, the average 1H-NMR spectra of the four herbs show a close resemblance, but also exhibit observable differences in the finer details. (PDF 905 KB)

13020_2012_166_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Additional file 2: Figure S2. PCA loading plot for the PC1 and PC2. The number next to the symbol shows the average chemical shift of the binned data. (PDF 65 KB)

13020_2012_166_MOESM3_ESM.pdf

Additional file 3: Table S1. Statistical significance estimates (P values, Bonferroni-corrected) of differences of metabolite concentrations between pairs of samples by Student t-tests (N = 5). (PDF 16 KB)

13020_2012_166_MOESM4_ESM.pdf

Additional file 4: Figure S3.1H NMR spectra of ginsenosides showing the resonance of Rg1 (black, solid) and Rd (red, broken line). Among the observed peaks, a well-resolved peak at 3.85 ppm, a location free from interfering signals in the ginseng extract spectra, is identified. (PDF 165 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Chan, P.H., Zheng, K.Y., Tsim, K.W. et al. Metabonomic analysis of water extracts from Chinese and American ginsengs by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance: identification of chemical profile for quality control. Chin Med 7, 25 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1749-8546-7-25

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1749-8546-7-25