Abstract

We recently encountered an unusual case of Composite lymphoma (CL) in the anterior mediastinum arising in a 37-year-old woman who presented initially with continuous pain in the right shoulder and chest. The woman had been suffered from continuous pain for three months before she went to our department of cardiovascular surgery. Chest computed tomography scan revealed the oval space-occupying lesion of anterior mediastinum. Surgery was performed and the disease was diagnosed pathologically as CL which composed of nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, via hematoxylin-eosin (H&E), immunohistochemical staining and in situ hybridization.

Virtual Slides

The virtual slide(s) for this article can be found here: http://www.diagnosticpathology.diagnomx.eu/vs/1975431863528091.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Composite lymphoma (CL), which is defined as the coexistence of two morphologically and phenotypically distinct types of lymphoid neoplasms occurring in a single anatomic organ or tissue, is unusual [1, 2]. The combination might include Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) with B-cell or a T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), B-cell NHL with T -cell NHL, or two distinct B-cell or T-cell NHLs at the same anatomic site [2–6]. The concept of "composite lymphoma" was first put forward by Custer RP to expatiate the occurrence of more than one histological type of lymphoma in the same patient [7]. The incidence of CL is low, varying from 1% to 4.7% [8]. In our present study, we report a case of composite nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma (NSHL) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) in the anterior mediastinum. The clinical, histopathologic, immunohistochemical features and the clinical prognosis are discussed.

Case presentation

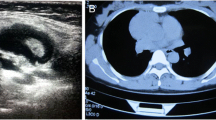

The 37-year-old woman presented with a three-month history of continuous pain in the right shoulder and chest. She was taken to our department of cardiothoracic surgery. Physical examination was remarkable for palpable lymph nodes in the bilateral supraclavicular fossae. Chest computed tomography (CT) revealed an oval mass located in the anterior mediastinum. Circumambient lung tissue was involved. Haematological findings were: WBC 15.40 × 109/L, platelets 364 × 109/L, prothrombin time 10.3 sec. Her erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), blood biochemistry, electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine, urine analysis and the endocrine profile were within normal range except hemoglobin (106 g/L) and tumor specific growth factor (67 U/ML). The abdominal ultrasonography did not reveal any other abnormality.

The surgery was performed with the patient under general anesthesia and left lateral decubitus position. The procedure revealed an oval tumor, volume of which was 7 cm × 4.5 cm × 2.5 cm, in the anterior mediastinum and circumambient lung tissue was involved. Pathologic findings during surgery showed that the tumor was off-white with obscure boundaries and hard in consistence (Figure 1). The result of pathology hinted that the tumor maybe malignant lymphoma. The tumor and circumambient lung tissue which was involved were excised.

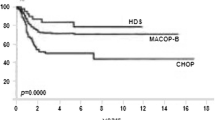

Histology showed the tumor was nodular and different nodules were separated by collagen fibers (Figure 2A). There were two morphologically and immunophenotypically distinct components. The great mass of nodules showed a pleomorphic cellular infiltrate containing lymphocyte, eosinophile granulocyte, neutrophile granulocyte and numerous large Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg cells. The Reed-Sternberg cells were positive for CD30, CD15 and MUM1 but negative for CD20, CD79a, CD3, Pax-5, CD68, bcl-6, CD10, CD45, Igκ, Igλ and epithelial membrane antigen (Figure 2B, Figure 3A). Other nodules displayed sheets of relatively uniform large lymphoid cells with typical morphologic features of large cell lymphoma which showed uniform expression of CD20, CD79a, MUM1, CD45, Igλ, Pax-5 and absence of CD30, CD15, CD3, CD10, bcl-6, Igκ, CD68 and epithelial membrane antigen (Figure 2C, Figure 3B). All the primary antibodies are listed in Table 1. Neither cell population showed makers of EBV infection by EBER in situ hybridization (PanPath Company, Amsterdam, Netherlands). On the basis of histomorphology at light microscopy, the presence of immunohistochemical staining and in situ hybridization, a diagnosis of CL, combination of NSHL and DLBCL, in the anterior mediastinum was made. The patient received six courses of CHOP chemotherapy (a course of treatment every two weeks) and twenty three times radiotherapy (Gross Tumor Volume, GTV = 40Gy/20f; Planning Target Volume, PTV = 36 Gy/20f). After treatment, lymph nodes in the bilateral supraclavicular fossa disappeared. The total follow-up period was thirty three months after surgery. The repeated CT scans, abdominal ultrasonography and tumor specific growth factor every three months revealed no recurring or residual lesion.

Histological examination. (A)The tumor is nodular and different nodules are separated by collagen fibers. Different nodules show different histologic features (H&E × 40). (B) Pleomorphic cellular infiltrate containing lymphocytes, eosinophils, neutrophils and large Reed-Sternberg cells (arrows) (H&E × 400). (C) Other nodules display sheets of relatively uniform large lymphoid cells with typical morphologic features of large cell lymphoma (H&E × 100).

Discussion

Clinically, manifestation of CL is similar with that of ordinary lymphoma. The true incidence of CL occurring in the same tissue is difficult to estimate because of the pathologist and the classification system used. In the study of more than one thousand of cases for Working Formulation of NHL, the incidence of CL varied between 1 and 4.7% [6, 9]. The combination of classical Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma coexisting in the same tissue is rare and much more uncommon than other combinations. To our best knowledge, Kim et al firstly reported the patient with CL consisting of an admixture of HL and NHL in the left axillary node [10]. According to our literature search, only six cases showing combination of classical Hodgkin lymphoma and DLBCL within the same site simultaneously were described [11–15]. The clinical data of all previously published cases of classical Hodgkin lymphoma associated with DLBCL was listed in Table 2.

Lymphoma, generally, is defined as monoclonal proliferation of lymphocyte (T cell, B cell or natural killer cell) while polyclonal hyperplasia is generally regarded as reactive lymphoid proliferation. However, the pathogenesis of CL is not clear. Many studies of CL using molecular techniques have proved true biclonality as well as a common origin from the same clonal progenitor cell and suggested different biological mechanisms in different tumors [4, 13, 14, 16–18]. As far as the combination of HL and B-cell NHL is concerned, the most common form is nodular lymphocyte predominance Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL) with large cell lymphoma [6]. The both components may occur synchronously and successively. More and more researchers swing the pendulum towards that HL and B-cell NHL coexisting in the same tissue might originate from a common precursor by molecular techniques [13, 14, 19]. Bräuninger et al studied CL from one patient (classic HL and a follicular lymphoma in the same lymph node). A V gene rearrangement and some somatic mutations were shared by Reed-Sternberg cells and follicular lymphoma cells, which provided proof of a common B-cell precursor [16]. Schmitz et al summarized six cases of such CL in which the HLs were combined in two cases with follicular lymphoma, and in one case each with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia, marginal zone lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma and DLBCL. The composite lymphomas had been analyzed by single-cell PCR analysis for rearranged IgV genes and a clonal relationship was confirmed [16, 20, 21]. In the cases of NLPHD with associated LBCL, the presence of a clonal population in the NLPHD component that was identical or related to the neoplastic clone of the associated LBCL has been found. In addition, in situ hybridization has shown that both L&H cells and LBCL cells expressed the same type of the immunoglobulin light chain messenger RNA. Single L&H cells, the Reed-Sternberg cells variants in NLPHD, were isolated from immunostained tissue sections by micromanipulation, and the IgH complementarity determining region (CDR) III of the cells was amplified by PCR. The sequences from the L&H cells also were related to those from the corresponding LBCL cells. All of these findings strongly suggested that NLPHD was related to the corresponding LBCL [19, 22].

We have analysed our case of a patient with NSHL, presenting a distinct focal area of proliferation composed of large monomorphous NHL cells in the anterior mediastinum. On immunohistochemical analysis, typical Reed-Sternberg cells expressed CD 30, CD 15 and MUM1 antigens, but lacked CD20 and Pax-5 immunoreactivity. The large monomorphous NHL cells reacted with the antibodies CD20, CD79a, MUM1 and Pax-5, showing a B-cell-related phenotype, and no other expression of the antigens was expressed by Reed-Sternberg cells expect MUM1 protein. Unfortunately, we could not perform further molecular investigations in order to determine whether a clonal relationship between the Reed-Sternberg cells and the DLBCL cells does exist in our patient. Thus, we can only offer speculations on this intriguing issue according to the existing literatures. Two main possibilities may be considered, as follows in Table 3.

First, both NSHL and DLBCL originate from a common precursor B cell, that is, the same abnormal B cell gives rise to the different neoplastic disorders through distinct bilogical pathways. Bellan et al reported that immunoglobulin heavy chain gene (IgH) rearrangement was found in the VH region in Reed-Sternberg cells and LBCL cells. A repeated VH4DH3JH4 segment was observed in Reed-Sternberg cells, while a repeated VH3DH3JH4 segment was found in LBCL cells. The two populations showing the same JH and DH segments with no variation from the respective sequence indicated they derived from a common B cell origin [14]. In addition, clonally related Vκgene rearrangement was also found in both Reed-Sternberg cells and DLBCL cells which revealed a common lymphoma precursor [15]. During the course of neoplastic progression, both NSHL and DLBCL were assumed to share one or more transforming events, which might play an important role in the up-regulation or down-regulation of tumor associated antigens. For example, Pax-5 is an important B-cell transcription factor and expressed regularly in the Reed-Sternberg cells of HL. But this antigen could be lost in the Reed-Sternberg cells, which was caused by some transforming event in the tumorigeness of CL [13]. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) was identified in a subset of cases of HL and in some NHL, particularly those associated with immunodeficiency [23]. However, EBV infection did not seem to be the primary event in this tumorigeness by assessing the data of table 3. Second, Paulli et al suggested the NSHL and DLBCL components were totally unrelated and their occurrence together within the same lymph node simply represented a coincidental occurrence [12]. However, this result might be inconclusive which was supported by immunohistochemical research and lacked the molecular studies.

Primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL) is the most critical disease in distinguishing with DLBCL of CL. PMBCL is currently classified as a subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, which has distinct clinical and molecular features, many of which are similar with that of NSHL [24]. PMBCL shows the clinical presentation of a large anterior mediastinal mass in a young female, but it does not express immunoglobulin [24–26]. In our present study, large B-cell lymphoma cells expressed Igλ which could help us differ it from PMBCL. In addition, there is a lack or defective expression of HLA class I or II molecules and an over-expression of MAL or interleukin-4 inducible gene FIG1 is always found in PMBCL [27]. Secondly, mediastinal gray zone lymphoma (MGZL), which represents two kinds of manifestation, should also be considered in differential diagnosis. In some cases, the histologic appearance is more suggestive of MLBCL, but the immunohistochemical features are characteristic of classical HL with expression of CD15 and CD30, and weak or absent CD20 positivity. In other cases, the histology is more reminiscent of classical HL, but the immunophenotype is more suggestive of a DLBCL. In our case, morphologic and immunohistochemical features have shown two different neoplasms. The Reed-Sternberg cells were positive for CD30, CD15 but negative for CD20, CD79a, CD45, while large B-cell lymphoid cells showed expression of CD20, CD79a, CD45 and absence of CD30, CD15. Other histological differential diagnoses, including leukocythemia, carcinoma metastaticum, sarcoma, reactive lymphoid proliferation and collision tumor [28] should be cautiously considered. Careful observation under the microscope and properly performed immunohistochemistry could be helpful for a correct diagnosis [2].

There is no evidence that the clinical course of CL differs significantly from that of discordant lyomphoma or lymphoma in general when the component with the poorest prognosis is taken into consideration. Although the case is rare and the number of reported cases is small, most scholars suggest that the prognosis is depended by the unfavorable component of CL. Therefore, therapeutic decision should be based on this ingredient [2, 29]. The treatment for the patient we presented was CHOP chemotherapy and adjuvant radiation therapy after surgery. The necessary follow-up examination among thirty three months disclosed there was no palindromic lesion.

Conclusion

We report a rare case of CL, combination of nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, arising in the anterior mediastinum. By molecular techniques, many scholars have proved the two different ingredients tend to origin from the same clonal progenitor cell. EBV infection is not essential transforming event during the course of tumorigenesis. The contribution of immunohistochemstry plays an important role in differential diagnoses. Therapeutic decision of CL should be based on the component of which malignant degree is higher.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

References

National Cancer Institute sponsored study of classifications of non-Hodgkin's lymphomas: summary and description of a working formulation for clinical usage. The Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Pathologic Classification Project. Cancer. 1982, 49: 2112-2135.

Kim H, Hendrickson R, Dorfman RF: Composite lymphoma. Cancer. 1977, 40: 959-976. 10.1002/1097-0142(197709)40:3<959::AID-CNCR2820400302>3.0.CO;2-3.

Dargent JL, Lespagnard L, Meiers I, Bradstreet C, Heimann P, De Wolf-Peeters C: Composite follicular lymphoma and nodular lymphocyte predominance Hodgkin's disease. Virchows Arch. 2005, 447: 778-780. 10.1007/s00428-005-0008-1.

Caleo A, Sánchez-Aguilera A, Rodríguez S, Dotor AM, Beltrán L, de Larrinoa AF, Menárguez FJ, Piris MA, García JF: Composite Hodgkin lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma: two clonally unrelated tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003, 27: 1577-1580. 10.1097/00000478-200312000-00012.

Kaleem Z, McGuire MH, Caracioni AC, Leonard RL, Pathan MH, Lessmann EA, Chan WC: Composite B-cell and T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the tibia. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005, 123: 215-221. 10.1309/P6LUADHRL9TXFW2M.

Kim H: Composite lymphoma and related disorders. Hematopathology. 1993, 99: 445-451.

Custer RP: Pitfalls in the diagnosis of lymphoma and leukemia from pathologist's point of view. Proceedings of Second National Conference--New York American Cancer Society. 1954, 554-557.

Thirumala S, Esposito M, Fuchs A: An unusual variant of composite lymphoma: a short case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000, 124: 1376-1378.

Hoppe RT: Histologic variation in non-Hodgkin's lymphomas: commentary. Cancer Treat Rep. 1981, 65: 11-12.

Kim H, Dorfman RF: Morphological studies of 84 untreated patients subjected to laparotomy for the staging of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Cancer. 1974, 33: 657-674. 10.1002/1097-0142(197403)33:3<657::AID-CNCR2820330311>3.0.CO;2-D.

Hell K, Hansmann ML, Pringle JH, Lauder I, Fischer R: Combination of Hodgkin's disease and diffuse large cell lymphoma: an in situ hybridization study for immunoglobulin light chain messenger RNA. Histopathology. 1995, 27: 491-499. 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1995.tb00319.x.

Paulli M, Rosso R, Kindl S, Boveri E, Sirchi M, De Medici A, Invernizzi R, Magrini U: Nodular sclerosing Hodgkin's disease and large cell lymphoma. Immunophenotypic characterization of a composite case. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1992, 421: 271-275. 10.1007/BF01611185.

Huang Q, Wilczynski SP, Chang KL, Weiss LM: Composite recurrent Hodgkin lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. One clone, Two faces. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006, 126: 222-229. 10.1309/DDGLWRV3KR9164G7.

Bellan C, Lazzi S, Zazzi M, Lalinga AV, Palummo N, Galieni P, Marafioti T, Tonini T, Cinti C, Leoncini L, Pileri SA, Tosi P: Immunoglobulin Gene Rearrangement Analysis in Composite Hodgkin Disease and Large B-Cell Lymphoma: Evidence for Receptor Revision of Immunoglobulin Heavy Chain Variable Region Genes in Hodgkin-Reed-Sternberg Cells?. Diagnostic Molecular Pathology. 2002, 11: 2-8. 10.1097/00019606-200203000-00002.

Rosenquist R, Menestrina F, Lestani M, Küppers R, Hansmann ML, Bräuninger A: Indications for peripheral light-chain revision and somatic hypermutation without a functional B-cell receptor in precursors of a composite diffuse large B-cell and Hodgkin's lymphoma. Lab Invest. 2004, 84: 253-262. 10.1038/labinvest.3700025.

Bräuninger A, Hansmann ML, Strickler JG, Dummer R, Burg G, Rajewsky K, Küppers R: Indentification of common germinal-center B-cell precursors in two patient with both Hodgkin's disease and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Eng J Med. 1999, 340: 1239-1246. 10.1056/NEJM199904223401604.

Savage KJ, Monti S, Kutok JL, Cattoretti G, Neuberg D, De Leval L, Kurtin P, Dal Cin P, Ladd C, Feuerhake F, Aguiar RC, Li S, Salles G, Berger F, Jing W, Pinkus GS, Habermann T, Dalla-Favera R, Harris NL, Aster JC, Golub TR, Shipp MA: The molecular signature of mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma differs from that of other diffuse large B-cell lymphomas and shares features with classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2003, 102: 3871-3879. 10.1182/blood-2003-06-1841.

Fend F, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Kumar S, Beaty MW, Blum L, Sorbara L, Jaffe ES, Raffeld M: Composite Low Grade B-Cell Lymphomas with Two Immunophenotypically Distinct Cell Populations Are True Biclonal Lymphomas A Molecular Analysis Using Laser Capture Microdissection. American Journal of Pathology. 1999, 154: 1857-1866. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65443-0.

Greiner TC, Gascoyne RD, Anderson ME, Kingma DW, Adomat SA, Said J, Jaffe ES: Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin's disease associated with large- cell lymphoma: analysis of Ig gene rearrangements by V-J polymerase chain reaction. Blood. 1996, 88: 657-666.

Schmitz R, Renné C, Rosenquist R, Tinguely M, Distler V, Menestrina F, Lestani M, Stankovic T, Austen B, Bräuninger A, Hansmann ML, Küppers R: Insights into the multistep transformation process of lymphomas: IgH-associated translocations and tumor suppressor gene mutations in clonally related composite Hodgkin's and non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Leukemia. 2005, 19: 1452-1458. 10.1038/sj.leu.2403841.

Küppers R, Sousa AB, Baur AS, Strickler JG, Rajewsky K, Hansmann ML: Common germinal-center B-cell origin of the malignant cells in two composite lymphomas, involving classical Hodgkin's disease and either follicular lymphoma or B-CLL. Mol Med. 2001, 7: 285-292.

Ohno T, Huang JZ, Wu G, Park KH, Weisenburger DD, Chan WC: The tumor cells in nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin disease are clonally related to the large cell lymphoma occurring in the same individual. Direct demonstration by single cell analysis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2001, 116: 506-511. 10.1309/KY8C-LCYN-QHJ6-4C6R.

Kingma DW, Medeiros LJ, Barletta J, Raffeld M, Mann RB, Ambinder RF, Jaffe ES: Epstein-Barr virus is infrequently identified in non-Hodgkin's lymphomas associated with Hodgkin's disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994, 18: 48-61. 10.1097/00000478-199401000-00005.

Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H, et al.: World Health Organization classification of tumors. Pathology and genetics of tumors of hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. 2001, IARC Press: Lyon, France

Lamarre L, Jacobson JO, Aisenberg AC, Harris NL: Primary large cell lymphoma of the mediastinum. A histologic and immunophenotypic study of 29 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989, 13: 730-739. 10.1097/00000478-198909000-00002.

Rosenwald A, Wright G, Leroy K, Yu X, Gaulard P, Gascoyne RD, Chan WC, Zhao T, Haioun C, Greiner TC, Weisenburger DD, Lynch JC, Vose J, Armitage JO, Smeland EB, Kvaloy S, Holte H, Delabie J, Campo E, Montserrat E, Lopez-Guillermo A, Ott G, Muller-Hermelink HK, Connors JM, Braziel R, Grogan TM, Fisher RI, Miller TP, LeBlanc M, Chiorazzi M, Zhao H, Yang L, Powell J, Wilson WH, Jaffe ES, Simon R, Klausner RD, Staudt LM: Molecular diagnosis of primary mediastinal B cell lymphoma identifies a clinically favorable subgroup of diffuse large B cell lymphoma related to Hodgkin lymphoma. J Exp Med. 2003, 198: 851-862. 10.1084/jem.20031074.

Faris JE, LaCasce AS: Primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2009, 7: 125-133.

El Demellawy D, Ross C, Sur M, Alowami S: Synchronously diagnosed lymph nodal collision tumor of malignant melanoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma: case report. Diagn Pathol. 2007, 2: 34-10.1186/1746-1596-2-34.

Travis LB, Gonzalez CL, Hankey BF, Jaffe ES: Hodgkin's disease following non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Cancer. 1992, 69: 2337-2342. 10.1002/1097-0142(19920501)69:9<2337::AID-CNCR2820690923>3.0.CO;2-K.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

YG and KL designed the study, performed the histological evaluation, and drafted the manuscript.

QG participated histological diagnosis and revising the manuscript.

ZQ was involved in literature search and preparing the material.

WW and JL participated in immunohistochemical evaluation.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Guohua Yu, Lingling Kong contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, G., Kong, L., Qu, G. et al. Composite lymphoma in the anterior mediastinum: a case report and review of the literature. Diagn Pathol 6, 60 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-1596-6-60

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-1596-6-60