Abstract

Background

Despite being a core business of medicine, end of life care (EoLC) is neglected. It is hampered by research that is difficult to conduct with no common standards. We aimed to develop evidence-based guidance on the best methods for the design and conduct of research on EoLC to further knowledge in the field.

Methods

The Methods Of Researching End of life Care (MORECare) project built on the Medical Research Council guidance on the development and evaluation of complex circumstances. We conducted systematic literature reviews, transparent expert consultations (TEC) involving consensus methods of nominal group and online voting, and stakeholder workshops to identify challenges and best practice in EoLC research, including: participation recruitment, ethics, attrition, integration of mixed methods, complex outcomes and economic evaluation. We synthesised all findings to develop a guidance statement on the best methods to research EoLC.

Results

We integrated data from three systematic reviews and five TECs with 133 online responses. We recommend research designs extending beyond randomised trials and encompassing mixed methods. Patients and families value participation in research, and consumer or patient collaboration in developing studies can resolve some ethical concerns. It is ethically desirable to offer patients and families the opportunity to participate in research. Outcome measures should be short, responsive to change and ideally used for both clinical practice and research. Attrition should be anticipated in studies and may affirm inclusion of the relevant population, but careful reporting is necessitated using a new classification. Eventual implementation requires consideration at all stages of the project.

Conclusions

The MORECare statement provides 36 best practice solutions for research evaluating services and treatments in EoLC to improve study quality and set the standard for future research. The statement may be used alongside existing statements and provides a first step in setting common, much needed standards for evaluative research in EoLC. These are relevant to those undertaking research, trainee researchers, research funders, ethical committees and editors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

There are 57 million deaths each year. Despite being a core business of medicine, end of life care (EoLC) is neglected [1]. Although some people have excellent EoLC, many do not die as they would wish [2]. A major barrier is the lack of quality research; treatments, clinical guidelines and services are limited by a lack of evidence [3, 4]. Surveys, qualitative studies and reviews recommend that EoLC research is feasible and ethical [4] but, funding of EoLC research is poor [1, 5] and lacks common research guidance. Thus, randomised trials of EoLC treatments and services remain rare, often limited by poor recruitment, high attrition, bias, confounding and small sample sizes [6–8]. There are challenges capturing relevant outcomes in frail patients who may lack capacity, raising ethical reservations [3, 6, 7, 9, 10]. Research evaluating EoLC is characterised as too slow, too expensive and frequently not producing useful results [2]. There is a need to improve research methods to evaluate models of service delivery and complex service level interventions in EoLC and identify good research practices to aid future studies. In response, the Methods Of Researching End of Life Care (MORECare) collaboration was established by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) and National Institutes of Health Research (NIHR) to identify, appraise and synthesise ‘best practice’ methods for research evaluating EoLC. This paper reports the total integrated results from MORECare and the resulting guidance statement.

Methods

Design

The multiple problems of patients receiving EoLC mean that treatments and interventions are complex, combining symptom relief with physical, emotional, social and spiritual care. We took as a starting point the MRC Guidance for Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions [11]. We planned a phased study (Figure 1). This involved prioritising areas of uncertainty and difficulties in terms of best research practice in EoLC and developing a statement of best research practice to complement existing tools that aid the conduct and reporting of research, such as the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) [12] or Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies (STROBE) for observational studies [13]. We conducted systematic literature reviews, transparent expert consultations (TEC) involving consensus methods of nominal group and online voting, and stakeholder workshops to identify challenges and best practice in EoLC research, including: participation recruitment, ethics, attrition, integration of mixed methods, complex outcomes and economic evaluation. We synthesised all findings to develop the guidance statement.

Definitions

We defined EoLC as the total or holistic care of a person during the last part of their life, from the point at which a person’s health is in a progressive state of decline, usually in the last year, the last months, weeks or days of life [14].

Interventions

EoLC includes both generalist and specialist services and is offered across primary, secondary and tertiary care settings [6]. EoLC offers integrated treatments and interventions including specific pharmacological or psychological therapies, education and clinical guidelines (for example, care pathways), patient registers, and direct multi-professional care [6, 15].

Expert panel

We established a panel of experts in trials, quantitative, qualitative and mixed method research, within and outside palliative care, patients/consumers, service providers, clinicians, commissioners, national policy makers and voluntary sector representatives (see Acknowledgements).

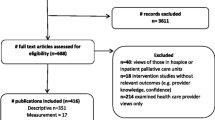

Phase I. Scoping and systematic reviews

We scoped the literature to prioritise areas for systematic literature reviews or consultation (Figure 1). We searched six electronic data bases and reference lists for either systematic reviews of EoLC services, or papers recommending methods in EoLC research, as well as papers recommending methods for the evaluation of complex interventions. Three systematic literature reviews were subsequently conducted, see Table 1[16–18].

Phase II. Transparent Expert Consultation (TEC) and Stakeholder Workshops

Five topics were selected for TEC based on results from the scoping (a lack of empirical data) and expert opinion (Figure 1). TEC is a rapid means to agree on recommendations for action, using nominal group techniques to generate recommendations and online ranking to ascertain consensus (see Table 2) [19]. Each TEC followed the same structure. In addition, we considered the conduct and reporting of research in three further workshops - two with patients/consumers and one with clinicians and policy makers. Expert panel meetings were also held every four months and considered randomisation and alternative design approaches, the challenges for policy makers and stakeholders, and the implementation of research findings into practice.

Phase III. Synthesis

We planned from the outset to integrate the results from all components to produce overall guidance on ‘best practice’ (Figure 1). We developed the MORECare statement, based on the strongest recommendations from all components of MORECare, as evolving good practice guidance to design and conduct research. This approach is similar to that for tools to support evaluative research (for example, CONSORT, STROBE). Recommendations which went beyond specific study designs were collated for national/international groups.

Ethics

The research ethics committee of the University of Manchester (reference number 10328) approved the TEC component of MORECare. All TEC participants gave written consent.

Results

The literature reviews and scoping together identified 15,695 papers, of these 62 were included in the three systematic reviews [16–18]. The results of the scoping and expert panel identified five main areas of contention/uncertainty that required TEC on: ethics [20], statistics (managing missing data, attrition, and response shift), [21] outcome measurement, [22] mixed method research, [23] and health economics [24]. Attendees of the five TECs totalled 140, with 133 responses to the five online consultations (Table 3). The three stakeholder workshops included 19 patients/carers and 12 clinicians. The integrated top ranked recommendations and synthesis with the literature formed: the MORECare statement detailing 36 best practice solutions for research in EoLC to improve study quality and set a standard for research in the future (Table 4); and 13 national/international MORECare recommendations to improve the environment for the development and evaluation of interventions in EoLC (Table 5).

Study design recommendations

Three shortcomings for the MRC guidance [11] were identified: (a) moving from feasibility and piloting to implementation without robust evaluation; (b) failing to develop the feasibility of the evaluation methods alongside the feasibility of treatment/intervention; and (c) lack of a theoretical framework underpinning treatment/intervention. In EoLC this has resulted in a lack of pragmatic trials, or, when attempted, trials that fail. There is a need to build simultaneously the intervention and research methods. Understanding the process of the intervention and how it might work is important. Our systematic reviews and expert panel discussions proposed that considerations about implementation be integrated into all phases of evaluation rather than only at the end. This approach ensures that when the intervention is ready to be rolled out, it is feasible with the context and processes of implementation understood, planned for and resourced. The MORECare statement addresses these challenges, see Table 4 and Figure 2.

Specific aspects in design and execution

Patient/caregiver participation

The evidence from the systematic reviews of quantitative and qualitative studies and from the MORECare consultations found that patients (even those close to death) and families were consistently willing to engage in research [17]. Factors reducing such willingness were mainly physical (symptoms, frailty), cognitive impairment or lack of mental capacity. Participating in research was a positive experience for most patients and carers. A minority experienced distress related to the characteristics of the participants, research design (face to face interviews and studies with a clear relevance to care were preferred), or the way it was conducted (very long information sheets, physically struggling to sign a consent form, and poor accommodation of fluctuating symptoms increasing distress). Sometimes the distress, mostly about discussing difficult issues, was acceptable and managed [17].

Ethics

Despite the problems of research among individuals who are frail and may sometimes lack cognitive capacity, there was unanimous support across all components of MORECare that it is ethically desirable to offer patients and families the opportunity to be involved in research [20]. Concerns were expressed about an over-protective culture, which sometimes denies patients and families the choice to be involved in research. It can be unethical to assume that patients should not be offered the opportunity purely because they have an advanced disease. Inclusion and exclusion criteria may need to be broadened to allow participation, taking into account any effects on design (Table 4). Methods should take account of expected potential loss of mental capacity. Ethical review and especially governance arrangements were sometimes inappropriate hindrances. Proposals are made for regulatory and legal change to address these (Table 5).

Clinician participation

Clinicians are often the first point of contact for EoLC research. There are two aspects: their own willingness to participate and the role they play in aiding the recruitment of patients and/or families. There were mixed reports about health professionals’ attitudes to EoLC research across systematic literature reviews and TECs. Problems can result in poor recruitment due to overt or subconscious control of the recruitment for, or the conduct of, research (sometimes called gatekeeping), which may be influenced by the attitudes towards, and prioritisation of, a research project or research as a whole.

Outcome measures and QALYs

Just as treatments in palliative and EoLC are complex, so are outcomes. There is a need to capture changes in symptoms and physical, emotional, social or spiritual needs, at a time when a patient’s condition is deteriorating or death approaches. The measures required will need to be, paradoxically, comprehensive yet brief and sensitive [22]. The MORECare project identified validated outcome measures specifically for palliative care. Beyond traditional psychometric requirements of face, content, and construct validity, the MORECare statement includes other requirements for outcome measures (Table 4). There were, however, strongly opposing views as to whether the commonly used composite measure of outcomes, quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), was appropriate or suitable in EoLC [24]. Debates centred on whether QALYs should be used in palliative care. Participants’ questioned the applicability of QALYs as a measure of outcome for people with life limiting illness and concern that they fail to demonstrate cost-effectiveness. Others argued that QALYs were the most widely used and until alternative measures for palliative care were available the use of QALYs should continue.

Statistical approaches; handling attrition and missing data

Attrition and missing data are inevitable in EoLC research. A study which does not have attrition due to death or worsening illness may justifiably be criticised for recruiting the wrong patients [21]. We considered two main approaches to this issue. Firstly, wherever viable, missing data are minimised, using measures which are as short and simple as possible. Where appropriate, proxy ratings from carers or staff may fill gaps which would otherwise exist. Secondly, attrition and missing data are anticipated. Whilst posing a challenge for statistical analysis, they should not be seen as a fault of the study design. Instead, the causes of ‘missingness’ require careful planning for and reporting. We suggest a classification of attrition relevant to EoLC studies to describe causes of attrition (attrition due to death, attrition due to illness, attrition at random). There may not be a single correct statistical analysis applicable for all forms of missing data; however, we suggest an attempt to model the impact of different forms of imputation to test the robustness of study conclusions under different assumptions. These approaches are emergent areas of methodological development and require further debate to identify clear solutions. The statistical analysis plan should include this uncertainty and be prepared and tested while testing the feasibility of the intervention (Figure 2).

Discussion

This is the first comprehensive research specifically aimed at producing evidence-based guidance for researching treatments and services in EoLC. Our findings propose using randomised trials and other quasi-experimental or observational designs, which may be appropriate when randomisation is not appropriate. Alternative designs would build on traditional RCT methodology and the MRC framework by integrating observational or natural experiment methods, and taking account of implementation aspects, rather than taking a totally different approach. Mixed methods can be employed at all phases of development and evaluation. We found that patients and families value participation in research. Consumer or patient collaboration in developing studies can be valuable in ensuring ethical methods and in addressing the concerns of ethics committees. MORECare also concluded that it is ethically desirable to offer patients and families the opportunity to take part in research and it may be unethical not to offer this opportunity purely on the grounds of progressive disease. Outcome measures should be short, responsive to change and ideally used for both clinical practice and research. More controversially we propose that attrition and missing data should be expected in studies, and does not indicate poor design – indeed, a lack of attrition may mean that the wrong population has been studied. Attrition should be planned for in advance. A new classification of attrition and missing data was developed. Implications for implementation need to be considered at all stages of the project.

MORECare identified the need to involve relevant methodologists, researchers familiar with the challenges in EoLC and consumers/patients/families in studies. The multiple problems of patients mean that interventions are complex, combining symptom relief and physical, emotional, social and spiritual care. The teams required to conduct research in this field, therefore, may also need to be large and complex. Such teams require management, and funding bodies may need to take account of the costs involved.

Our conclusions on the ethical issues raised by EoLC research challenge earlier thinking, especially that randomisation is unethical [17]. There is growing support for the need for research into EoLC to improve practice. The conclusion from the ethics’ TEC was that it can be unethical not to offer research to this group of individuals. Concerns about approaching patients and families who are distressed or very ill are understandable, and this has often led ethics committees or others to raise concerns regarding research in EoLC. However, the vulnerability of patients and families is often simplistically understood. Koffman et al. identified five aspects: (i) communicative; (ii) institutional; (iii) deferential; (iv) medical; and (v) social vulnerability, which are relevant in EoLC and other situations, and might provide a broader framework for assessment [26].

The new MORECare classification for attrition: ADD – attrition due to death; ADI attrition due to illness; and AaR attrition at random – is novel, as is our statement that attrition should not be seen as an indication of poor research. Traditionally, guidelines propose that attrition of 5% or lower is inconsequential, whereas 20% or greater is unacceptable because of bias [27]. However, such a guideline fails to distinguish the reasons for attrition. Data which are missed because patients have died is very different to that missed because a patient has withdrawn consent or because they are symptomatic. To impute data such as a quality of life score for a patient who has died seems inappropriate. Whereas imputing data for patients who have moved away or are missed at random would be different. Thus, we designed a classification system for attrition to extend the commonly used classification in clinical trials of missing completely at random (MCAR), missing at random (MAR) and missing not at random (MNAR). We envisage our classification could be used as an adjunct to understand trial data better. Further, while attrition introduces potential for bias, our argument is that a lack of attrition may indicate a different bias, that a less relevant population has been included. In theory, attrition can introduce selection bias in randomized trials. Conversely, a recent secondary analysis from 10 trials evaluating treatment of musculoskeletal disorders, challenged this; the authors found no indication that attrition altered the results in favour of either treatment or control [28]. Work is needed to explore the effect of attrition on bias in EoLC studies, and the best ways to impute data. We believe that our proposed classification will help to clarify reporting and may well be applicable in other populations where attrition is high, for example those who are elderly or frail.

Our findings that outcome measures should be short and easy to use support and further develop conclusions from a large European Network on outcome measurement in palliative and EoLC [29]. We propose further that outcome measurement should be timed to balance the effect of the intervention and loss of data through attrition. Tang and McCorkle proposed an alternative approach, of conducting weekly interviews to ensure adequate data in end of life care studies [30]. While this can be appropriate in some circumstances, it may cause undue interview burden, and we believe the MORECare recommendation of careful timing is more appropriate.

Our proposal that outcome measures used in research should also be valuable in clinical practice is novel, as this is not a usual requirement when assessing outcome measures, although it relates to aspects in the COSMIN (COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health status Measurement INstruments) checklist of face validity and responsiveness to change [31]. In EoLC there are now many different outcome measures. The European survey identified more than 100 different outcome measures in palliative care research, but 94 of these were used fewer than 10 times [32]. There is a need for standardisation around the few best validated short scales which are widely used, perhaps with core and add on modules [33], so that in the future results from studies may be pooled.

Policy makers, clinicians and patients responding to the MORECare consultation raised the need for research results to be timely to influence service developments. MORECare concluded that robust evaluation data can be found beyond RCTs. This is increasingly raised as an option in research generally [34] and in the most recent formats of the MRC guidance [11]. Secondary analysis of existing data sets, including data collected nationally or in routine clinical practice, and quasi-experimental, epidemiological and qualitative or especially mixed methods can be helpful, especially if the original data is of high quality [34]. Some good examples of secondary analysis of data are available in the USA, where data on hospital activity and costs are routinely available [35].

We attempted to identify the key areas of methodological difficulty in EoLC research; however, we were limited to conducting only five TECs and three systematic reviews, and ideally would have conducted more, especially regarding more specific recommendations on recruitment methods, alternatives to the standard RCT (such as the use of cluster [36] or fast-track trials [37]) and the use of quasi-experimental designs. We see the MORECare statement as a first step, which ideally will be expanded and refined through further testing. Arguably we could have conducted a more traditional Delphi consultation rather than TEC, but the TEC approach allowed a more interactive discussion by allowing novel and sometimes challenging proposals. It did limit our international membership – and only the outcomes summit (which was conducted alongside an international congress) had truly international participation. A particular strength was the involvement of patients and caregivers in all our TECs and throughout the MORECare project, which is uncommon in the development of guidance on good research practice. This involvement resulted in novel proposals, for example, the recommendation for researchers to attend ethics committee meetings with patients, caregivers or consumers came from a patient.

Conclusions

This research study, which integrated data from three systematic reviews and five TECs, resulted in a statement (the MORECare Statement) of 36 best practice solutions for immediate practice and 13 wider recommendations for national and international consideration. The results show how ethical research is possible, what is required of outcome measures, the need for clinical and academic collaborations and how mixed method research can be reported. Some points in the statements challenge current research practice, for example with new recommendations regarding anticipating, planning for and managing attrition and missing data. Other points require longer term change, for example legal change to permit advanced consent. The MORECare Statement sets clear standards on good research practice in evaluating services and treatments in EoLC. The Statement is relevant to those designing, funding and reviewing studies and should be used alongside existing statements. It provides a first step in setting common, much needed standards for evaluative research in EoLC.

Abbreviations

- ADD:

-

Attrition due to death

- ADI:

-

Attrition due to illness

- AaR:

-

Attrition at random

- CIS:

-

Critical interpretive synthesis

- CONSORT:

-

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials

- COSMIN:

-

COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health status Measurement Instruments

- EoLC:

-

End of life care

- MORECare:

-

Methods of Researching End of Life Care

- MRC:

-

Medical Research Council

- NIHR:

-

National Institutes of Health Research

- QALYs:

-

Quality adjusted life years

- RCTs:

-

Randomised controlled trials

- SPC:

-

Specialist palliative care

- STROBE:

-

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies

- TEC:

-

Transparent expert consultation.

References

End-of-life care: the neglected core business of medicine. Lancet. 2012, 379: 1171-10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60490-5.

Department of Health: End of Life Care Strategy - Promoting High Quality Care for Adults at the End of Life. 2008, London: Department of Health

Higginson IJ: It would be NICE to have more evidence?. Palliat Med. 2004, 18: 85-86. 10.1191/0269216304pm884ed.

Kendall M, Harris F, Boyd K, Sheikh A, Murray SA, Brown D, Mallinson I, Kearney N, Worth A: Key challenges and ways forward in researching the “good death”: qualitative in-depth interview and focus group study. BMJ. 2007, 334: 521-10.1136/bmj.39097.582639.55.

Sleeman KE, Gomes B, Higginson IJ: Research into end-of-life cancer care–investment is needed. Lancet. 2012, 379: 519-10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60230-X.

Shipman C, Gysels M, White P, Worth A, Murray SA, Barclay S, Forrest S, Shepherd J, Dale J, Dewar S, Peters M, White S, Richardson A, Lorenz K, Koffman J, Higginson IJ: Improving generalist end of life care: national consultation with practitioners, commissioners, academics, and service user groups. BMJ. 2008, 337: a1720-10.1136/bmj.a1720.

Lorenz KA, Lynn J, Dy SM, Shugarman LR, Wilkinson A, Mularski RA, Morton SC, Hughes RG, Hilton LK, Maglione M, Rhodes SL, Rolon C, Sun VC, Shekelle PG: Evidence for improving palliative care at the end of life: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2008, 148: 147-159. 10.7326/0003-4819-148-2-200801150-00010.

Chochinov HM, Kristjanson LJ, Breitbart W, McClement S, Hack TF, Hassard T, Harlos M: Effect of dignity therapy on distress and end-of-life experience in terminally ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12: 753-762. 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70153-X.

Gysels M, Higginson IJ: Improving Supportive and Palliative Care for Adults with Cancer: Research Evidence. 2004, London: NICE

Higginson IJ, Finlay IG, Goodwin DM, Hood K, Edwards AG, Cook A, Douglas HR, Normand CE: Is there evidence that palliative care teams alter end-of-life experiences of patients and their caregivers?. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003, 25: 150-168. 10.1016/S0885-3924(02)00599-7.

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M: Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008, 337: a1655-10.1136/bmj.a1655.

Zwarenstein M, Treweek S, Gagnier JJ, Altman DG, Tunis S, Haynes B, Oxman AD, Moher D, group C, Pragmatic Trials in Healthcare group: Improving the reporting of pragmatic trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. BMJ. 2008, 337: a2390-10.1136/bmj.a2390.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, STROBE Initiative: The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007, 370: 1453-1457. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X.

National Institutes of Health: National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Conference Statement on Improving End-of-Life Care. 2004, USA: NIH Concensus Development Program

Walshe C, Caress A, Chew-Graham C, Todd C: Implementation and impact of the Gold Standards Framework in community palliative care: a qualitative study of three primary care trusts. Palliat Med. 2008, 22: 736-743. 10.1177/0269216308094103.

Higginson IJ, Evans CJ: What is the evidence that palliative care teams improve outcomes for cancer patients and their families?. Cancer J. 2010, 16: 423-435. 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181f684e5.

Gysels MH, Evans C, Higginson IJ: Patient, caregiver, health professional and researcher views and experiences of participating in research at the end of life: a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012, 12: 123-10.1186/1471-2288-12-123.

Evans CJ, Harding R, Higginson IJ, on behalf of MORECare: ‘Best practice’ in developing and evaluating palliative and end-of-life care services: a meta-synthesis of research methods for the MORECare project. Palliat Med. 2013, 10.1177/0269216312467489.

Yardley L, Beyer N, Hauer K, McKee K, Ballinger C, Todd C: Recommendations for promoting the engagement of older people in activities to prevent falls. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007, 16: 230-234. 10.1136/qshc.2006.019802.

Gysels M, Evans CJ, Lewis P, Speck P, Benalia A, Preston NJ, Grande G, Short V, Owen-Jones E, Todd C, Higginson IJ, on behalf of MORECare: MORECare research methods guidance development: Recommendations for ethical issues in palliative and end-of-life care research. Palliat Med. In press

Preston NJ, Fayers P, Walters SJ, Pilling M, Grande G, Short V, Owen-Jones E, Evans CJ, Benalia A, Higginson IJ, Todd C, on behalf of MORECare: Recommendations for managing missing data, attrition and response shift in palliative and end of life care research: Part of the MORECare research methods guidance on statistical issues. Palliat Med. In press

Evans CJ, Benalia A, Preston NJ, Grande G, Gysels M, Short V, Daveson BA, Bausewein C, Todd C, Higginson IJ, on behalf of MORECare: The selection and use of outcome measures in palliative and end-of- life care research: the MORECare international consensus workshop. J Pain Symptom Manage. In press

Farquhar M, Preston NJ, Short V, Evans CJ, Walshe C, Grande G, Benalia H, Anscombe E, Higginson IJ, Todd C: MORECare research methods guidance development: Recommendations for using mixed methods to develop and evaluate complex interventions in palliative and end of life care [abstract]. Palliat Med. 2012, 26: 419.

Preston NJ, Short V, Hollingworth W, McCrone P, Grande G, Evans CJ, Anscombe E, Benalia A, Higginson IJ, Todd C: MORECare research methods guidance development: Recommendations for health economic evaluation in palliative and end of life care research [abstract]. Palliat Med. 2012, 26: 541.

Perera R, Heneghan C, Yudkin P: Graphical method for depicting randomised trials of complex interventions. BMJ. 2007, 334: 127-129. 10.1136/bmj.39045.396817.68.

Koffman J, Morgan M, Edmonds P, Speck P, Higginson IJ: Vulnerability in palliative care research: findings from a qualitative study of black Caribbean and white British patients with advanced cancer. J Med Ethics. 2009, 35: 440-444. 10.1136/jme.2008.027839.

Dumville JC, Torgerson DJ, Hewitt CE: Reporting attrition in randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2006, 332: 969-971. 10.1136/bmj.332.7547.969.

Hewitt CE, Kumaravel B, Dumville JC, Torgerson DJ, Trial attrition study group: Assessing the impact of attrition in randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010, 63: 1264-1270. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.01.010.

Bausewein C, Simon ST, Benalia H, Downing J, Mwangi-Powell FN, Daveson BA, Harding R, Higginson IJ: Implementing patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) in palliative care–users’ cry for help. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011, 9: 27-10.1186/1477-7525-9-27.

Tang ST, McCorkle R: Appropriate time frames for data collection in quality of life research among cancer patients at the end of life. Qual Life Res. 2002, 11: 145-155. 10.1023/A:1015021531112.

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, Bouter LM, de Vet HC: The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010, 63: 737-745. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.006.

Harding R, Simon ST, Benalia H, Downing J, Daveson BA, Higginson IJ, Bausewein C: The PRISMA Symposium 1: outcome tool use. Disharmony in European outcomes research for palliative and advanced disease care: too many tools in practice. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011, 42: 493-500. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.06.008.

Simon ST, Higginson IJ, Harding R, Daveson BA, Gysels M, Deliens L, Echteld MA, Radbruch L, Toscani F, Krzyzanowski DM, Costantini M, Downing J, Ferreira PL, Benalia A, Bausewein C, PRISMA: Enhancing patient-reported outcome measurement in research and practice of palliative and end-of-life care. Support Care Cancer. 2012, 20: 1573-1578. 10.1007/s00520-012-1436-5.

Harvey S, Rowan K, Harrison D, Black N: Using clinical databases to evaluate healthcare interventions. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2010, 26: 86-94. 10.1017/S0266462309990572.

Morrison SR, Penrod J, Cassel B, Caust-Ellenbogen M, Litke A, Spragens L, Meier DE, Palliative Care Leadership Centers’ Outcomes Group: Cost savings associated with US hospital palliative care consultation programs. Arch Int Med. 2008, 168: 1783-1790. 10.1001/archinte.168.16.1783.

Costantini M, Ottonelli S, Canavacci L, Pellegrini F, Beccaro M: The effectiveness of the Liverpool care pathway in improving end of life care for dying cancer patients in hospital. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011, 11: 13-10.1186/1472-6963-11-13.

Higginson IJ, Costantini M, Silber E, Burman R, Edmonds P: Evaluation of a new model of short-term palliative care for people severely affected with multiple sclerosis: a randomised fast-track trial to test timing of referral and how long the effect is maintained. Postgrad Med J. 2011, 87: 769-775. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2011-130290.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/11/111/prepub

Acknowledgements

MORECare was funded by the NIHR and managed by the MRC as part of the Methodology Research Programme (MRP) (number: G0802654/1). MORECare aimed to identify, appraise and synthesise ‘best practice’ methods to develop and evaluate palliative and EoLC, particularly focusing on complex service-delivery interventions and reconfigurations. Principal investigator: Irene J Higginson. Co-principal investigator: Chris Todd. The members of MORECare are: Co-investigators - Peter Fayers, Gunn Grande, Richard Harding, Matthew Hotopf, Penney Lewis, Paul McCrone, Scott Murray, Myfanwy Morgan; Project expert panel - Massimo Costantini, Steve Dewar, John Ellershaw, Claire Henry, William Hollingworth, Philip Hurst, Tessa Inge, Jane Maher, Irene McGill, Elizabeth Murray, Ann Netten, Sheila Payne, Roland Petchey, Wendy Prentice, Deborah Tanner and Celia A Taylor; Researchers - Hamid Benalia, Catherine J Evans, Marjolein Gysels, Nancy J Preston and Vicky Short. Morag Farquhar was supported by a Macmillan Cancer Support Post-Doctoral Fellowship. Irene J Higginson is an NIHR Senior Investigator. Additionally, we thank staff in the Cicely Saunders Institute researchers meeting, in particular Drs Fliss Murtagh, Gao Wei and Thomas Osborne, for their comments on an earlier draft of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

IJH designed the study, led the application for funding, oversaw the MORECare project, contributed to TECs and systematic reviews, led the integration of results, drafted and revised the paper and is the guarantor. CE managed the MORECare project day to day, led one systematic review and one TEC, contributed to protocol development and the integration of the results. GG and CT were co-applicants of the study and contributed to protocol development, TECs, systematic reviews and stakeholder workshops. CT led the Manchester component. NP managed the Manchester component of MORECare, TEC on-line voting and stakeholder workshops. MM, PMcC, RH, SAM, PL, PF and MH were co-applicants of the study, helped to develop the protocol, contributed to TECs and Expert Group presentations. HB, MF and MG led individual TECs or systematic reviews and prepared material to be presented to the Expert Group. All authors commented on and revised the draft paper. All members of the MORECare project contributed to the design and execution of the studies and integration. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Higginson, I.J., Evans, C.J., Grande, G. et al. Evaluating complex interventions in End of Life Care: the MORECare Statement on good practice generated by a synthesis of transparent expert consultations and systematic reviews. BMC Med 11, 111 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-111

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-111