Abstract

In this paper, we discuss numerical methods for fractional order problems. Some nonstandard finite difference schemes are presented and investigated. The application in the simulation of a fractional-order Brusselator system is hence presented. By means of some numerical experiments, we show the effectiveness of the proposed approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Recently, fractional calculus has gained an increasing popularity due to the wide range of applications in fields including engineering, chemistry, finance, physics, seismology and so on.

Although the discussion on derivatives of noninteger order dates back to almost as far as the development of the classical theory of integer-order differential calculus, only at the end of the nineteenth century it has been realized the great enhancements that could be achieved by exploiting the power of fractional calculus; by means of fractional differential equations (FDEs) it is indeed possible to describe, in a natural way, real-life phenomena with memory effect and systems exhibiting anomalous diffusion [1].

The publication of some cornerstone books completely devoted to fractional calculus (we just cite here the works of Oldham and Spainer [2], Samko, Kilbas and Marichev [3], Miller and Ross [4], Podlubny [5], Diethelm [6] and Mainardi [7]) has successively played a considerable role in disseminating the subject. A variety of recent books [8–13] have also been published to illustrate applications of FDEs and methods for their solution.

In most cases, the solution of a FDE does not exist in terms of a finite number of elementary functions; it is therefore fundamental to device numerical methods in order to practically evaluate approximated solutions by means of difference schemes or other alternative approaches (e.g., see [14–19]).

A major difficulty in the numerical treatment of FDEs is the presence of the long and persistent memory, which is related to the nonlocal nature of fractional derivative operators. From a practical point of view, storing and taking into account all the past history of the solution is usually a very demanding task.

In the presence of nonlinearities, these difficulties are amplified by the need of solving, at each step, some nonlinear algebraic systems whenever implicit schemes are adopted to cope with stability issues.

Nonstandard finite difference (NSFD) schemes have been introduced [20, 21] with the aim of avoiding full implicit schemes, which are computationally expensive, but at the same time preserving some of the main essential physical properties of the solution such as, for instance, positivity, monotonicity or convergence towards a stable steady-state.

The central aim of this work is to apply NSFD schemes within the context of fractional-order problems and study their potentials in replicating some of the main properties of the true solution [22–25]. In particular, the paper is concerned with the numerical simulation, by means of some ad hoc devised NSFD schemes, of a fractional-order Brussellator system; the stability properties of the system are analyzed and we show that the proposed NSFD methods allow to preserve stability in the numerical solution.

The paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we briefly review the main definitions concerning fractional derivatives and FDEs and we introduce NSFD methods. Section 3 is devoted to discuss the main problems in applying NSFD schemes to fractional-order problems. In Section 4, we analyze stability of the fractional-order Brusselator system, and we present some suitably devised NSFD for this system. By means of some numerical simulations, in Section 5, we show the stability preserving properties of the proposed schemes and we compare the results with those provided by a classical method. Finally, some concluding remarks are given in Section 6.

2 Preliminaries and notations

In this section, some basic definitions and properties in the theory of the fractional calculus are presented; moreover, we introduce the main aspects concerning nonstandard discretization methods.

2.1 Fractional derivatives and FDEs

Derivatives of fractional order have been introduced in several ways. The Riemann-Liouville (RL) differential operator of order is defined as

where is the Euler gamma function, is the smallest integer such that and and denote the standard derivatives of integer order.

Despite its importance from an historical point of view (the RL approach has been the first definition introduced for fractional derivatives), very often it is of little use in practical applications; indeed, when used in FDEs it allows to couple the equation with initial conditions expressed as the limit of a fractional integral as in

which does not have a clear physical meaning.

To overcome these difficulties, the alternative approach of the Caputo (C) differential operator of order has been proposed according to

The major advantage of the above definition is that when used in FDEs it is possible to couple the equation with classical initial conditions of Cauchy type, thus to obtain an initial value problem in the standard form

It is important to remark that the two definitions are strongly correlated by means of the relationship

where, for a function f assumed sufficiently smooth at , is the th degree Taylor polynomial for f centered at

When , and hence and , we simply have

A further approach is the Grünwald-Letnikov (GL) operator defined as

where the weights are the coefficients in the power series expansion of , i.e.,

and, from a practical point of view, they can be evaluated recursively by means of the following recurrence:

Under suitable assumptions of regularity, the RL and GL operators coincides, i.e.,

As a consequence, it is possible to establish a relationship also between the C and GL operators by means of the formula

which, for , becomes

The GL operator, used in connection with (4) or (5) provides a practical and convenient method for numerically solving FDEs with the Caputo operator. By truncating the summation in (2), it is possible to approximate the solution of the problem (1) as

This method has been extensively studied in literature (e.g., see [18, 26]) and the numerical solution obtained by (6) converges to true solution with order 1 as . Method (6) will form the basis on which NSFD methods will be devised in the subsequent section.

We introduce the following result concerning the weights of the GL discretization scheme (6), which will be used later on.

Lemma 1 Let and the coefficients in the GL operator. Then for any

-

1.

,

-

2.

.

Proof The proof is an immediate consequence of the recursive relationship stated in (3). □

2.2 Nonstandard discretization

NSFD schemes were firstly proposed by Mickens [20, 21] for either ODEs or PDEs and, successively, their use has been investigated in several fields (see, for instance, [27–31]).

To describe the main aspects of NSFD schemes, we consider an ODE in the form

where λ is a, possibly vector, parameter. Given a mesh-grid , that just for simplicity we assume to be equispaced with step-size , NSFD schemes are constructed by following two main steps: (1) the derivative at the left-hand side of (7) is replaced by a discrete representation in the form

where is an approximation of ; (2) the nonlinear term in (7) is replaced by a nonlocal discrete representation depending on some of the previous approximations. The resulting scheme therefore reads as

The discrete derivate on the left-hand side is a generalization of the classical discrete representation for the first derivative that is obtained by using . The denominator function is a function of the step-size h and must fulfill the consistency condition

to ensure that the discrete representation in (8) converges to the corresponding continuous derivative as . Examples of denominator functions fulfilling (10) are h, , , and so forth.

Other than by fulfilling the consistency condition (10), there are however some other criteria for choosing a suitable denominator function. The main aim is to achieve what is called the dynamic consistency: the solution of the discrete model (9) must satisfy some properties of particular importance for the original continuous model (7) (e.g., positivity, monotonicity, fixed points and so on).

To better describe this issue, we consider the linear problem which, as it is well known, monotonically converges to the steady-state whenever . The classical explicit Euler scheme, obtained with and does not preserve the monotonic convergence to 0 unless h is sufficiently small. It is instead easy to verify that the use of the nonstandard denominator function

ensures this desirable property for any value of h.

It is quite common to select the denominator function on the basis of the knowledge of the fixed points of f. For more general problems having the fixed points , , such that , after denoting

the denominator function ϕ can be chosen as

to ensure that the steady-state of the discrete model preserves the same stability properties of the original continuous model.

For the nonlinear terms on the right-hand side, several kinds of nonlocal discrete representations can be proposed, according to the nature of the problem under investigation. For instance, some examples of possible replacements are

3 NSFD for fractional differential equations

The use of NSFD schemes for fractional-order problems is a quite new subject and very few contributions are available in literature [32–34]. To apply NSFD schemes to FDEs, we have to take into account some peculiarities of fractional-order systems. Although the nonlocal discrete representation of the vector field can be assumed in an identical way as in (9), we must observe that, due to the nonlocal nature of derivative operators of fractional order, the discrete representation of the derivative must take into account all the past history of the solution as in (6). Thus, the counterpart of (9) for FDEs with order must be written in the form

when the GL discretization (6) is exploited as the underlying method for the construction of NSFD schemes.

The consistency condition (10) does not longer ensure the convergence of the discrete representation of the fractional derivative in (11) to its continuous definition. On the basis of (2), the modified consistency condition

must therefore be assumed. Some examples of denominator functions of this kind are

where and are the gamma Euler function and the Mittag-Leffler function respectively defined as

Although all the above functions satisfy the consistency condition (12), not all of them preserve the first order convergence of (6). Indeed, it is immediate to observe that to achieve this further goal it is necessary that p in (12) satisfies . Since most of the listed functions do not fulfill this requirement, it is obvious to expect a drop in the convergence order which could reduce to α, when , instead of being 1.

Despite the drop in the order of convergence, some of these denominator functions can be, however, useful to overcome stability issues. To this purpose, let us consider, also in this case, the linear test together with the explicit GL scheme obtained form (11) with . By following an analysis similar to that carried out in [35], we can easily see that in order to obtain a stable behavior we must require that the denominator function satisfies

Among the various denominator functions listed above, we will take into account the following two

Both of them fulfill the consistency condition (12) but just preserves order of convergence 1 since . Moreover, while satisfies for any values of h the stability requirement (13) only when λ is of small or moderate size, the function fulfills (13) in any circumstance. Thus, is expected to better work for preserving stability whereas seems more suitable for achieving higher accuracy.

4 Fractional-order Brusselator model: stability analysis and NSFD schemes

The fractional-order Brusselator [36] is a model of an autocatalytic chemical reaction, which is mathematically described as follows:

where , are activator and inhibitor variables and a, μ are external parameters (the relationship between them determines the system dynamics) [37].

To study the dynamics of this model, we consider its equilibrium point. Let and ; the equilibrium point E of (14) is the solution of

which can be easily determined as . The following result allows to summarize the dynamics of this equilibrium point [38].

Theorem 2 There exists a marginal value such that the equilibrium E is locally asymptotically stable if and it is unstable if .

Proof The steady state is locally asymptotically stable if all the eigenvalues λ of the Jacobian matrix

evaluated at the equilibrium point satisfy the following condition [39, 40]

The eigenvalues λ can be determined by solving the characteristic equation . Since the Jacobian matrix of the system (14) at the equilibrium point is

the eigenvalues of are

where and .

For consider the parabola and introduce the marginal value , . When the system has oscillatory, but stable modes; when unstable and more complicated dynamics arise [38]. □

The value of α is thus an additional bifurcation parameter, which switches the stable and unstable states of the system and changes the form of the limit cycle. When , the system has a unique limit cycle when and it has a stable limit cycle for [38].

Since system (14) does not have a general solution in closed form, numerical methods must be used to approximate its solutions; a major requirement is that the numerical schemes preserve the dynamics of the system.

To discretize the fractional-order nonlinear system (14), we propose and discuss some NSFD schemes applied in combination with the truncation of the GL operator as stated in (11).

In the following, we will denote with and the approximations for and . Furthermore, for brevity, we will put

and similarly

and

NSFD scheme 1: As a first nonstandard scheme, we make the replacement of the nonlinear term in the right-hand side of (14) by means of

The application of the truncated GL discretization (11) leads to

from which we can explicitly evaluate and as

Since we obtain and and hence the resulting NSFD scheme is

In our tests as the denominator function, we will use the function introduced in Section 3.

NSFD scheme 2: In our second nonstandard scheme, we use the replacement

By operating in a similar way as in the previous case, we can see that the resulting NSFD scheme can be expressed as

and the denominator function will be used.

NSFD scheme 3: In our last nonstandard scheme, we choose

and the resulting scheme is

When , this is a fully explicit scheme and it is the counterpart for FDEs of the classical forward Euler method. Anyway in our experiments, we will use both the denominator functions and to compare the behavior and the corresponding schemes will be denoted respectively as NSFD 3a and NSFD 3b.

To study positivity of the numerical approximations let us assume , and . A straightforward analysis allows us to identify the conditions under which positive iterations and are obtained. We summarize these conditions as follows:

Scheme 1: and .

Scheme 2: and .

Scheme 3: and .

5 Numerical simulations

We present in this section some numerical simulations. To compare the results obtained with the NSFD schemes investigated in this paper, we use the reference solution provided by the Adams-Bashforth-Moulton (ABM) method implemented in [41], whose stability properties have been investigated in [42].

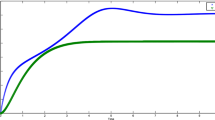

In the first simulation, we consider the case , , with the initial value . Since , the marginal value of Theorem 2 is , and hence unstable modes are expected, as we show in Figure 1, where the reference solution evaluated by the ABM method is plotted in the time domain and in the phase plane.

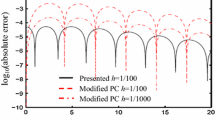

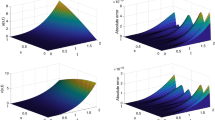

In Figure 2, we present the results obtained by the NSFD schemes with a step-size on the integration interval . As we can clearly see, all the NSFD schemes provide the expected unstable modes and the trajectories converge quite well towards the same limit cycle. Although all the methods seem to work in a satisfactory way, the results obtained but the NSFD scheme 2 better replicate the behavior of the reference solution of Figure 1.

In the second experiment, we consider a problem with , and . Since and the threshold value of Theorem 2 is , a stable mode is expected as we can see from the plots in Figure 3 obtained again by the ABM method.

Also in this case we observe, see Figure 4, that all the NSFD schemes show a stable mode in agreement with the theoretical findings and with the reference solution of Figure 3. In this case, the integration has been performed on the interval .

In Table 1, we compare the results for the approximations of obtained by the proposed schemes for , , , on the interval with an increasing number N of steps. The errors with respect to the reference solution are reported together with the estimation of the order of convergence (EOC) obtained as .

As expected from the discussion in Section 3, a drop in the order of convergence is achieved by using the denominator function whilst the function allows to preserve order 1. Moreover, all the schemes allow to obtain quite accurate results.

6 Concluding remarks

In this paper, some NSFD schemes have been investigated for the numerical solution of the fractional-order Brusselator differential system. Some different denominator functions and nonlocal terms have been proposed and the results have been compared with a classical Adams-Bashforth-Moulton method for FDEs. From the numerical experiments, we observed that NSFD schemes allow to replicate quite well the behavior of the true solution, and hence they are a useful tool for detecting the main stability properties for the problem under investigation and for similar problems.

References

Kempfle S, Schäfer I, Beyer H: Fractional calculus via functional calculus: theory and applications. Nonlinear Dyn. 2002, 29(1–4):99–127.

Oldham KB, Spanier J: The Fractional Calculus. Academic Press, New York; 1974.

Samko SG, Kilbas AA, Marichev OI: Fractional Integrals and Derivatives. Gordon & Breach, Yverdon; 1993. (Theory and applications, edited and with a foreword by S. M. Nikol’skiĭ, translated from the 1987 Russian original, revised by the authors)

Miller KS, Ross B A Wiley-Interscience Publication. In An Introduction to the Fractional Calculus and Fractional Differential Equations. Wiley, New York; 1993.

Podlubny I Mathematics in Science and Engineering 198. In Fractional Differential Equations. Academic Press, San Diego; 1999.

Diethelm K Lecture Notes in Mathematics 2004. In The Analysis of Fractional Differential Equations. Springer, Berlin; 2010.

Mainardi F: Fractional Calculus and Waves in Linear Viscoelasticity. Imperial College Press, London; 2010.

Baleanu D, Diethelm K, Scalas E, Trujillo JJ Series on Complexity, Nonlinearity and Chaos 3. In Fractional Calculus. World Scientific, Hackensack; 2012.

Butzer PL, Westphal U: An introduction to fractional calculus. In Applications of Fractional Calculus in Physics. Edited by: Hilfer R. World Scientific, Singapore; 2000:1–85.

Caponetto R, Dongola G, Fortuna L, Petráš I Series on Nonlinear Science, Series A 72. In Fractional Order Systems: Modeling and Control Applications. World Scientific, Singapore; 2010.

Kilbas AA, Srivastava HM, Trujillo JJ North-Holland Mathematics Studies 204. In Theory and Applications of Fractional Differential Equations. Elsevier, Amsterdam; 2006.

Magin R: Fractional Calculus in Bioengineering. Begell House Publishers, Redding; 2006.

Sabatier J, Agrawal O, Machado JT: Advances in Fractional Calculus: Theor. Developments and Appl. in Physics and Engineering. Springer, Berlin; 2007.

Diethelm K, Ford NJ, Freed AD: A predictor-corrector approach for the numerical solution of fractional differential equations. Nonlinear Dyn. 2002, 29(1–4):3–22.

Diethelm K, Ford N, Freed A, Luchko Y: Algorithms for the fractional calculus: a selection of numerical methods. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2005, 194(6):743–773.

Garrappa R, Popolizio M: On the use of matrix functions for fractional partial differential equations. Math. Comput. Simul. 2011, 81(5):1045–1056.

Garrappa R, Popolizio M: On accurate product integration rules for linear fractional differential equations. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2011, 235(5):1085–1097.

Lubich C: Discretized fractional calculus. SIAM J. Math. Anal. 1986, 17(3):704–719.

Moret I, Novati P: On the convergence of Krylov subspace methods for matrix Mittag-Leffler functions. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 2011, 49(5):2144–2164.

Mickens RE, Smith A: Finite-difference models of ordinary differential equations: influence of denominator functions. J. Franklin Inst. 1990, 327: 143–149.

Mickens RE: Nonstandard Finite Difference Models of Differential Equations. World Scientific, River Edge; 1994.

Baleanu D, Mohammadi H, Rezapour S: Positive solutions of an initial value problem for nonlinear fractional differential equations. Abstr. Appl. Anal. 2012., 2012: Article ID 837437

Delavari H, Baleanu D, Sadati J: Stability analysis of Caputo fractional-order nonlinear systems revisited. Nonlinear Dyn. 2012, 67(4):2433–2439.

Deng W, Li C, Lü J: Stability analysis of linear fractional differential system with multiple time delays. Nonlinear Dyn. 2007, 48(4):409–416.

Jarad F, Abdeljawad T, Baleanu D: Stability of q -fractional non-autonomous systems. Nonlinear Anal., Real World Appl. 2013, 14: 780–784.

Garrappa R: On some explicit Adams multistep methods for fractional differential equations. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2009, 229(2):392–399.

Chen M, Clemence DP: Analysis of and numerical schemes for a mouse population model in hantavirus epidemics. J. Differ. Equ. Appl. 2006, 12(9):887–899.

Mickens RE: A nonstandard finite-difference scheme for the Lotka-Volterra system. Appl. Numer. Math. 2003, 45(2–3):309–314.

Mickens RE: Calculation of denominator functions for nonstandard finite difference schemes for differential equations satisfying a positivity condition. Numer. Methods Partial Differ. Equ. 2007, 23(3):672–691.

Roeger LIW: Nonstandard finite-difference schemes for the Lotka-Volterra systems: generalization of Mickens’s method. J. Differ. Equ. Appl. 2006, 12(9):937–948.

Roeger LIW: Dynamically consistent discrete Lotka-Volterra competition models derived from nonstandard finite-difference schemes. Discrete Contin. Dyn. Syst., Ser. B 2008, 9(2):415–429.

Moaddy K, Momani S, Hashim I: The non-standard finite difference scheme for linear fractional PDEs in fluid mechanics. Comput. Math. Appl. 2011, 61(4):1209–1216.

Momani S, Rqayiq AA, Baleanu D: A nonstandard finite difference scheme for two-sided space-fractional partial differential equations. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2012., 22(4): Article ID 1250079

Radwan AG, Moaddy K, Momani S: Stability and non-standard finite difference method of the generalized Chua’s circuit. Comput. Math. Appl. 2011, 62(3):961–970.

Galeone L, Garrappa R: On multistep methods for differential equations of fractional order. Mediterr. J. Math. 2006, 3(3–4):565–580.

Wang Y, Li C: Does the fractional Brusselator with efficient dimension less than 1 have a limit cycle? Phys. Lett. A 2007, 363(5–6):414–419.

Zhou T, Li C: Synchronization in fractional-order differential systems. Physica D 2005, 212(1–2):111–125.

Gafiychuk VV, Datsko B: Stability analysis and limit cycle in fractional system with Brusselator nonlinearities. Phys. Lett. A 2008, 372(29):4902–4904.

El-Sayed AMA, El-Mesiry AEM, El-Saka HAA: On the fractional-order logistic equation. Appl. Math. Lett. 2007, 20(7):817–823.

Matignon D: Stability results for fractional differential equations with applications to control processing. 2. In Computational Engineering in Systems Applications. IMACS, IEEE-SMC, Lille; 1996:963–968.

Garrappa, R: Predictor-corrector PECE method for fractional differential equations. MATLAB Central File Exchange [File ID: 32918] (2011)

Garrappa R: On linear stability of predictor-corrector algorithms for fractional differential equations. Int. J. Comput. Math. 2010, 87(10):2281–2290.

Acknowledgements

M.Y. Ongun and D. Arslan would like to acknowledge the partly financial support received from the Scientific Research Project Commission, SDU, Turkey, Project No: 2695-YL-11. The work of R. Garrappa has been carried out under the PRIN-MIUR project 2009F4NZJP.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work and typed, read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ongun, M.Y., Arslan, D. & Garrappa, R. Nonstandard finite difference schemes for a fractional-order Brusselator system. Adv Differ Equ 2013, 102 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1687-1847-2013-102

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1687-1847-2013-102