Abstract

Background

With decreasing global resources, a pervasive critical shortage of skilled health workers, and a growing disease burden in many countries, the need to maximize the effectiveness and efficiency of pre-service education in low-and middle-income countries has never been greater.

Methods

We performed an integrative review of the literature to analyse factors contributing to quality pre-service education and created a conceptual model that shows the links between essential elements of quality pre-service education and desired outcomes.

Results

The literature contains a rich discussion of factors that contribute to quality pre-service education, including the following: (1) targeted recruitment of qualified students from rural and low-resource settings appears to be a particularly effective strategy for retaining students in vulnerable communities after graduation; (2) evidence supports a competency-based curriculum, but there is no clear evidence supporting specific curricular models such as problem-based learning; (3) the health workforce must be well prepared to address national health priorities; (4) the role of the preceptor and preceptors’ skills in clinical teaching, identifying student learning needs, assessing student learning, and prioritizing and time management are particularly important; (5) modern, Internet-enabled medical libraries, skills and simulation laboratories, and computer laboratories to support computer-aided instruction are elements of infrastructure meriting strong consideration; and (6) all students must receive sufficient clinical practice opportunities in high-quality clinical learning environments in order to graduate with the competencies required for effective practice. Few studies make a link between PSE and impact on the health system. Nevertheless, it is logical that the production of a trained and competent staff through high-quality pre-service education and continuing professional development activities is the foundation required to achieve the desired health outcomes. Professional regulation, deployment practices, workplace environment upon graduation and other service delivery contextual factors were analysed as influencing factors that affect educational outcomes and health impact.

Conclusions

Our model for pre-service education reflects the investments that must be made by countries into programmes capable of leading to graduates who are competent for the health occupations and professions at the time of their entry into the workforce.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Contemporary pre-service education (PSE) for the health occupations and professions focuses on the acquisition of competencies that are needed immediately upon entry into the workforce - the knowledge, skills, attitudes and behaviours necessary for safe and effective practice [1]. With decreasing global resources, a pervasive critical shortage of skilled health workers in low- and middle-income countries, and growing disease burden in many countries, the need to maximize the effectiveness and efficiency of education and training for health workers has never been greater. International public health agencies, donors and governments are increasingly interested in making long-term investments to improve pre-service education.

Pre-service education (PSE) is used in this article to refer to the curriculum of studies that prepares a health provider for entry into practice of a health profession. (The term could also encompass preparation for practice of selected health occupations (pre-technical or pre-vocational education); however, we do not focus on these health provider cadres in this particular article.) High-quality PSE is both influenced by and facilitated by the interaction of several factors that promote competence within a defined scope of practice and within a collaborative, client-oriented health system that reflects local country needs. Jhpiego, an international non-governmental organization with many programmes supporting education for health workers, conducted an integrative review of the literature [2] to examine what is presently known about the essential components of pre-service education. An integrative review differs from a systematic review in that it allows inclusion of diverse methodologies (including both experimental and non-experimental studies), and takes a broader range of studies (both theoretical and empirical) into consideration [2]. We used this literature synthesis to develop a conceptual model that describes essential components of PSE and links them to desired outcomes and public health systems impact. The model will enable technical advisors, policymaking bodies and donors at the global and country levels to maximize the returns on their efforts to strengthen PSE systems. Specifically, the model can be used as a framework for prioritizing investments and as a guide for programme monitoring, evaluation and research to create a comprehensive evidence base for PSE strengthening.

Methods

Literature review methodology

Three sources were used for this review: electronic peer-reviewed literature, a ‘hand search’ of PSE bibliographies, and a focused literature search. First, the electronic peer-reviewed literature from 2000 to 2011 was searched within multiple health science databases (Pubmed, Medline, Cinahl, Google Scholar). Primary search terms focused on primary health providers in the global community (for example, physicians, nurses, midwives, clinical officers). Secondary search terms broadened the search to include a variety of specialties in which the health workers might be additionally prepared. Secondary search terms also included education, evaluation and regulation terms as well as aspects of the intended outcomes of pre-service education.

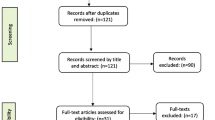

Two reviewers, working independently, scanned the titles and abstracts of the resulting 1,742 articles for their potential value to the issue of pre-service education. Articles were excluded from consideration if they: (1) reported on issues that were unlikely to have wide, generalizable application (for example, reports on a one-time or short-term experience at a single educational site); (2) were very narrow in focus (for example, an assessment of changes in courses or programme policies at a single institution, without intent to create models for replication); or (3) reported very limited sample sizes. In addition, articles that reported on postgraduate training events (continuing professional education and in-service education) were excluded, so that the PSE review would focus as precisely as possible on the essential elements and methods of pre-service education. Opinion pieces, editorials, commentaries, book chapters and project reports (grey literature) were also excluded. This yielded 124 articles with an explicit focus on pre-service education.

Second, a hand-search of existing PSE bibliographies yielded an additional 14 studies. Third, a focused literature search was conducted to address gaps in the previous search in specific topic areas that were underdeveloped. This search yielded an additional 82 unduplicated studies.

Articles were graded using a commonly accepted categorization scheme (the SORT approach), which is recommended for grading the quality of evidence published in the medical literature [3]. Table 1 depicts these grading criteria and the three quality tiers (the SORT tiers) that are represented by these evidence grades. A total of 97 articles (38 from the first source, 14 from the second source, and 45 from the third source) were retained after this process. Of these, 31 were graded as Tier 1, 15 as Tier 2, and 51 as Tier 3. Each of the 97 articles was also graded with respect to its focus on pre-service education, using the approach adopted for the Best Evidence in Medical Education reviews [4, 5]. Figure 1 depicts the inclusion and exclusion process.

Conceptual model

Five essential inputs to a comprehensive PSE system and several key influencing factors emerged as a result of the literature review. We created a conceptual model that depicts these five broad categories of inputs: students, curriculum, teachers/preceptors, infrastructure and management, and clinical practice sites (Figure 2). The expected educational output of these five elements is a competent graduate.

When competent graduates are deployed, we expect that their work will contribute to certain outcomes. We expect that they will implement life-saving practices and demonstrate professional behaviours, perform those practices to standard, and make a public health impact by contributing to decreases in morbidity and mortality. Several elements of the political, policy, social and workplace environments may either augment or impede the preparation of qualified graduates who are able to provide high-quality health services. Professional regulation emerges as an influencing factor of special significance.

Findings

Table 2 offers illustrative excerpts of findings from this integrative review. The findings are summarized below according to the model.

Students

Higher academic performance in secondary school was found to predict academic and clinical success; however, older age (postsecondary school) and gender did not contribute to either academic performance or student retention through graduation [6]. Targeted recruitment of qualified students from rural and low-resource settings was a particularly effective strategy for retaining students in vulnerable communities after graduation [7, 8]. An applicant’s specific expression of interest in the profession was important to student retention [9]. Student support strategies (for example, financial support and mentoring) offered some advantage to student retention and expanded student diversity [10–12].

Several studies attempted to identify the factors within PSE that promote the preparation of graduates for practice in low-resource, rural and remote settings, and increase the likelihood of their retention in those places. An applicant’s expression of positive attitudes and values toward rural practice as a career choice was directly influential [13]. The promotion of undergraduate clinical learning experiences in rural settings was shown to increase students’ comfort and thus might change their perceptions, attitudes and values about rural and remote practice [14–16].

Curriculum

Frank et al. explored the definition of the term competency-based education (CBE) [17]. While the authors found no consensus in the literature, the elements of a CBE appeared to be commonly acknowledged, and a competency-based curriculum was identified as one of the building blocks of CBE. Jayasekara, Schultz and McCutcheon explored problem-based learning (PBL) as one strategy for delivery of such a curriculum and identified some positive effects of PBL on knowledge acquisition [18–21]. A few studies attempted to compare the performance of graduates from programmes that used the PBL curriculum approach and reported some favourable findings with respect to impact of a PBL curriculum on improvement of attitudes toward clients, continuity of care, and access to specific services [22–24]. Studies that compared PBL to traditional curricula did not provide incontrovertible evidence to favour the design over any other, but they did not dispute it as a strategy to promote competency-based learning.

No contemporary studies were identified that compared the graduates educated within technical (leading to a certificate of completion) or academic (culminating in at least a baccalaureate degree) programmes of study in terms of competence in the workplace.

Formative and summative assessment of student learning is critical to CBE. A good deal of progress has been made in the development of valid and reliable tools for these assessments [25]. The objective, structured clinical examination (OSCE), which provides an integrated measure of knowledge and skills, was found to be of particular value [26].

Teachers and preceptors

The preparation and retention of skillful teachers is essential to the effective transfer of knowledge and skills from teachers to students [27–29]. Few studies indicated that a teacher in the health professions must be equally skilled as both a classroom teacher and a clinical preceptor or mentor (an individual who guides learning for one or more students in the clinical setting). Rather, the descriptive literature supports the importance of the preceptor/mentor role as complementary to the role of the academic educator [30]. The role of the preceptor has been particularly well explored, and studies confirm the need for preceptors to develop skills in clinical teaching, identification of student learning needs, assessment of student learning, and prioritizing and time management [31, 32].

No studies were found that directly address the issue of an appropriate teacher-to-student or preceptor-to-student ratio. Professional associations or country regulatory authorities sometimes set specific benchmarks and standards for this. A fundamental premise of competency-based education is that students must have both adequate time and sufficient clinical practice opportunities to acquire and demonstrate requisite knowledge and skills. A recent commentary [33] noted that pre-service education for midwives in Africa falls short in terms of adequate numbers of committed and well-informed preceptors to ensure optimal competency-building.

The literature supports the premise that administrative leaders in academic and clinical settings must be strongly supportive of each other’s roles and responsibilities [34, 35]. Academic administrators must be cognizant of the impact that clinical training has on the provision of client care. Facility administrators must appreciate the added and long-term value of having students in the clinical setting, as their presence encourages facility providers (both staff and preceptors) to keep up-to-date on the science that is the foundation for their clinical practice.

Infrastructure and management

Little in the literature speaks to the physical elements of the learning environment (for example, physical space) or teaching/learning tools (for example, textbooks and clinical anatomic models). However, several descriptive studies address elements of the infrastructure that warrant consideration. Modern, Internet-enabled medical libraries, skills and simulation laboratories, and computer laboratories to support computer-aided instruction are promoted as ‘essential enhancements’ to teaching and learning environments for the health occupations and professions [36–40].

Internet-based learning has been extensively studied, and several meta-analyses indicate that it can be as effective as traditional classroom-based learning in terms of student satisfaction and knowledge acquisition [41–45]. It does present challenges for the development and assessment of clinical skills, but these can be offset through the use of simulations and computer-based virtual patients [46, 47].

Clinical practice sites

All students must receive clinical practice learning opportunities in high-quality clinical learning environments, preferably where effective practice can be modeled by highly qualified teachers and preceptors [48, 49]. A wide variety of settings may be necessary in order to provide all students the individual learning opportunities that they require, given the lower frequency of occurrence of certain clinical conditions, and/or because of a high volume of students of various health occupations and professions who may be seeking similar experiences in a simultaneous timeframe (particularly in large teaching hospitals). Several systematic reviews offer modest support for the value of two or more health professions learning together in academic and clinical settings, to increase understanding of their complementary skills and contributions [50–52]. A few studies have demonstrated that multidisciplinary learning has positive effects on client outcomes, particularly in terms of better provider-client communication and service utilization [53–55].

Other influencing factors

Although other environmental factors influence opportunities for students to acquire competence by the time of their graduation and to progress along the continuum from novice to expert practitioner, few higher-tier studies address these factors in the context of pre-service education.

Professional regulation

The literature offers only descriptive information about the manner in which government and professional regulations affecting the education and training for the health professions (for example, accreditation standards, clinical practice guidelines, certification of graduates) are designed and implemented, and about their effectiveness in ensuring that schools meet standards and graduates achieve competencies [56, 57]. While regulation is widely viewed as essential to public protection, the literature about the relationship between engagement in continued professional development activities and subsequent changes in practice knowledge, skill or behaviour is very useful in any discussion about continued competence and re-licensure, but it offers only an indirect inferential link between pre-service education and professional practice.

The context of health service delivery

The degree to which countries succeed in reaching targets for health services coverage is affected not only by the numbers of practitioners, but also by having the right skill mix for national needs and the burden of disease [58, 59]. Another critical factor is the degree to which practitioners, including new graduates, are deployed to settings in which this skill mix can be used most effectively in time and place. Studies describing the adverse impacts of underutilization of human resources abound. Again, while the literature is full of studies addressing these and other characteristics of a supportive workplace environment, few studies do so in the context of pre-service education.

Outcomes and impact

Boelen and Woolard [60] argue that social, economic, cultural and environmental determinants of health must guide the strategic development of educational institutions. The graduates these programmes produce should both possess all of the competencies that are desirable, and also use them in professional practice. It could also be argued that educational programmes have a global accountability, given that they should be responsive to international standards and guidelines, and in light of the international mobility of the health workforce. The expected outcomes and the desired health impact of the high-quality health care services offered by graduates of pre-service education programmes are discussed below.

Intermediate outcomes

Although no studies were identified that linked elements of quality PSE to intermediate outcomes such as implementing life-saving practices and demonstrating professional behaviours, many high-quality studies do examine these outcomes in the context of continuing professional education [60–63].

Longer-term outcomes

Client satisfaction is an outcome assessed in a number of studies of inter-professional education. These studies generally report positive client responses to receiving team-based care [50]. Similarly, a number of studies assess the impact on satisfaction with care when clients and providers have similar ethnic and cultural backgrounds; clients generally indicate greater satisfaction with care when the provider is perceived as culturally sensitive [64].

The education of a sufficient number of healthcare workers addresses only part of the human resource crisis in many countries. Retention of health practitioners, both within the health occupation or profession for which an individual has been educated and in the location where the individual’s skills are needed, is an equally compelling challenge. Unfortunately, the literature is underdeveloped in terms of how production and retention are linked with PSE.

Health impact

Although there are many reports on the positive short- and longer-term outcomes of continuing professional education, very few studies make the link between PSE and these same outcomes, and even fewer examine the impact of PSE on health outcomes such as reduction in adverse events of care, improvement in the quality of life of clients, or reduction of morbidity and mortality. Nevertheless, a logical argument can be made that production of trained and competent staff through high-quality pre-service education and continuing professional development is the foundation required to achieve these desired outcomes.

Discussion

Fauveau, Sherratt and de Bernis set forth several key areas of work that must be addressed when planning for scale-up of human resources for maternal health [65]. They urge country governments to aim for quality over quantity. They urge a concentrated effort in PSE to address the need for promotion and development of: (1) high levels of technical competence; (2) appropriate curricula that ensure sufficient time for hands-on practical training, leading to competence in basic and emergency clinical tasks; (3) gender sensitivity; (4) excellent interpersonal communication and cultural competencies; and (5) motivation for the job. Based on our experience in PSE for maternal health and on our review of the literature on essential components of PSE, we support the agenda proposed by Fauveau and colleagues. However, good and complete evidence for each component of their agenda is still needed.

The literature review was designed to maximize reflection and discussion. We adopted a very structured grading method for inclusion and exclusion of articles, and involved several reviewers in this process, in order to identify and select objective studies. The literature proved to be rich in discussion of the elements of quality pre-service education but underdeveloped in discussion of proven linkages between PSE and quality healthcare service delivery, which is the intended outcome of competency-based education. The evidence from research already reported in the literature should form the basis of quality PSE programming. At the same time, a research agenda must be undertaken to advance our knowledge of factors essential to quality PSE and to address the gaps in the literature on the relationships and linkages between PSE and health outcomes [66].

Conclusions

The shortage of health workers in low- and middle-income countries demands an aggressive but structured evidence-based response. Sound pre-service education gives individuals entering the workforce the competencies they need to make an immediate impact as well as a foundation for future professional growth. Our conceptual model reflects the investments that countries must make to develop high-quality pre-service education programmes that are capable of producing competent graduates who are ready to enter the workforce. We urge a parallel and concurrent investment in: (1) developing and strengthening PSE programmes to ensure that they are consistent with current international education standards; (2) ongoing monitoring and evaluation of PSE programme quality and quality improvement initiatives; (3) continuing professional development, to update knowledge and skills of health cadres in an era of rapidly changing science, and to sustain health workers’ commitment to lifelong learning; and (4) long-term basic and operations research designed to demonstrate the value of any country’s investment in pre-service education and its link to practice.

Abbreviations

- CBE:

-

Competency-based education

- PBL:

-

Problem-based learning

- PSE:

-

Pre-service education

- SORT:

-

Strength of recommendation taxonomy.

References

Weinberger SE, Pereira AG, Lobst WF, Mechaber AJ, Bronze MS: Competency-based education and training in internal medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2010, 153: 751-756.

Whittemore R, Knafl K: The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005, 52: 546-553.

Ebell MH, Siwek J, Weiss BD, Woolf SH, Susman JL, Ewigman B, Bowman M: Simplifying the language of evidence to improve patient care: strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT): a patient-centered approach to grading evidence in the medical literature. J Fam Pract. 2004, 53: 111-120.

Kirkpatrick D: Great ideas revisited. Techniques for evaluating training programs. Revisiting Kirkpatrick’s four-level model. Train Dev. 1996, 50: 54-59.

Barr H, Freeth D, Hammick M, Koppel I, Reeves S: Evaluations of interprofessional education: a United Kingdom review of health and social care. 2000, London: CAIPE/BERA

Grumbach K, Chen E: Effectiveness of University of California postbaccalaureate premedical programs in increasing medical school matriculation for minority and disadvantaged students. JAMA. 2006, 296 (9): 1079-1085.

Rolfe IE, Ringland C, Pearson SA: Graduate entry to medical school? Testing some assumptions. Med Educ. 2004, 38 (7): 778-786.

Santee J, Garavalia L: Peer tutoring programs in health professions schools. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006, 70 (3): 70-

Pariyo GW, Kiwanuka SN, Rutebemberwa E, Okui O, Ssengooba F: Effects of changes in the pre-licensure education of health workers on health-worker supply. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009, 2: CD007018-

Norman IJ, Watson R, Murrells T, Calman L, Redfern S: The validity and reliability of methods to assess the competence to practise of pre-registration nursing and midwifery students. Int J Nurs Stud. 2002, 39: 133-145.

Kaye DK, Mwanika A, Sewankambo N: Influence of the training experience of Makerere University medical and nursing graduates on willingness and competence to work in rural health facilities. Rural Remote Health. 2010, 10: 1372-

Laven G, Wilkinson D: Rural doctors and rural backgrounds: how strong is the evidence? A systematic review. Aust J Rural Health. 2003, 11: 277-284.

Longombe AO: Medical schools in rural areas–necessity or aberration?. Rural Remote Health. 2009, 9: 1131-

Steinert Y, Mann K, Centeno A, Dolmans D, Spencer J, Gelula M, Prideaux D: A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to improve teaching effectiveness in medical education: BEME guide no. 8. Med Teach. 2006, 28: 497-526.

Udlis KA: Preceptorship in undergraduate nursing education: An integrative review. J Nurs Educ. 2008, 47 (1): 20-29.

Cook DA, Levinson AJ, Garside S, Dupras DM, Erwin PJ, Montori VM: Internet-based learning in the health professions: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008, 300: 1181-1196.

Cook DA: Instructional design variations in Internet-based learning for health Professions education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Med. 2011, 85 (5): 909-922.

Reeves S: The effectiveness of interprofessional education: Key findings from a new systematic review. J Interprof Care. 2010, 24 (3): 230-241.

Dornan T, Littlewood S, Margolis SA, Scherpbier A, Spencer J, Ypinazar V: How can experience in clinical and community settings contribute to early medical education? A BEME systematic review. Med Teach. 2006, 28: 3-18.

Littlewood S, Ypinazar V, Margolis SA, Scherpbier A, Spencer J, Dornam T: Early practical experience and the social responsiveness of clinical education: systematic review. BMJ. 2005, 331: 387-391.

Salvatori P: Reliability and validity of admissions tools used to select students for the health professions. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2001, 6: 159-175.

Mathews M, Rourke JTB, Park A: The contribution of Memorial University’s medical school to rural physician supply. Can J Rural Med. 2008, 13: 15-21.

Fowler J, Norrie P: Development of an attrition risk prediction tool. Brit J Nurs. 2009, 18: 1194-1200.

Mulholland J, Anionwu EN, Atkins R, Tappern M, Franks PJ: Diversity, attrition and transition into nursing. J Adv Nurs. 2008, 64: 49-59.

Greene S, Baird K: An exploratory, comparative study investigating attrition and retention of student midwives. Midwifery. 2009, 25: 79-87.

Cameron J, Roxburgh M, Taylor J, Lauder W: An integrative review of student retention in programmes of nursing and midwifery education: why do students stay?. J Clin Nurs. 2011, 20: 1372-1382.

Curran V, Rourke J: The role of medical education in the recruitment and retention of rural physicians. Med Teach. 2004, 26: 265-272.

Leon BK, Riise KJ: Wrong schools or wrong students? The potential role of medical education in regional imbalances of the health workforce in the United Republic of Tanzania. Hum Res Health. 2010, 8: 3-

Frank JR, Mungroo R, Ahmad Y, Wang M, De Rossi S, Horsley T: Toward a definition of competency-based education in medicine: a systematic review of published definitions. Med Teach. 2010, 32: 631-637.

Jayasekara R, Schultz T, McCutcheon H: A comprehensive systematic review of evidence on the effectiveness and appropriateness of undergraduate nursing curricula. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2006, 4: 191-207.

Williams SM, Beattie HJ: Problem based learning in the clinical setting–a systematic review. Nurse Educ Today. 2008, 28: 146-154.

Jones MC, Johnston DW: Is the introduction of a student-centred, problem-based curriculum associated with improvements in student nurse well-being and performance? An observational study of effect. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006, 43: 941-952.

Beers GW, Bowden S: The effect of teaching method on long-term knowledge retention. J Nurs Ed. 2005, 44: 511-514.

Crandall SJ, Reboussin BA, Michielutte R, Anthony JE, Naughton MJ: Medical students’ attitudes toward underserved patients: a longitudinal comparison of problem-based and traditional medical curricula. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2007, 12: 71-86.

Tamblyn R, Abrahamowicz M, Dauphinee D, Girard N, Bartlett G, Grand’Maison P, Brailovsky C: Effect of a community oriented problem based learning curriculum on quality of primary care delivered by graduates: historical cohort comparison study. BMJ. 2005, 331: 1002-

Akiode A, Fetters T, Daroda R, Okeke B, Oji E: An evaluation of a national intervention to improve the postabortion care content of midwifery education in Nigeria. Intl J Gynecol Obstet. 2010, 110: 186-190.

Walsh M, Bailey PH, Koren I: Objective structured clinical evaluation of clinical competence: an integrative review. J Adv Nurs. 2009, 65: 1584-1595.

Benor D: Faculty development, teacher training and teacher accreditation in medical education: Twenty years from now. Med Teach. 2000, 22: 503-512.

Marinopoulos SS, Dorman T, Ratanawongsa N, Wilson LM, Ashar BH, Magaziner JL, Miller RG, Thomas PA, Prokopowicz GP, Qayyum R, Bass EB: Effectiveness of continuing medical education. Evid Rep Technol Assess. 2007, 149: 1-69.

Robertson MK, Umble KE, Cervero RM: Impact studies in continuing education for health professions: update. J Cont Ed Health Prof. 2003, 23: 146-156.

Kaviani N, Stillwell Y: An evaluative study of clinical preceptorship. Nurse Educ Today. 2000, 20: 218-226.

Ramani S, Leinster S: AMEE guide No. 34: teaching in the clinical environment. Med Teach. 2008, 30: 347-364.

Brown D, White J, Leibbrandt L: Collaborative partnerships for nursing faculties and health service providers: what can nursing learn from business literature?. J Nurs Manag. 2006, 14: 170-179.

Casey M: Interorganisational partnership arrangements: a new model for nursing and midwifery education. Nurse Educ Today. 2010, 31: 304-308.

Madge B, Plutchak TS: The increasing globalization of health librarianship: a brief survey of international trends and activities. Health Infor Libr J. 2005, Suppl 1: 20-30.

Gantt LT: Strategic planning for skills and simulation labs in colleges of nursing. Nurs Econ. 2010, 28: 308-313.

Adler MD, Johnson KB: Quantifying the literature of computer-aided instruction in medical education. Acad Med. 2000, 75: 1025-1028.

Haigh J: Information technology in health professional education: why IT matters. Nurse Educ Today. 2004, 24: 547-552.

Pochciol JM, Warren JI: An information technology infrastructure to enable evidence-based nursing practice. Nurs Adm Q. 2009, 33: 317-324.

Cook DA, Levinson AJ, Garside S: Time and learning efficiency in internet-based learning: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2010, 15: 755-770.

Cook DA, Levinson AJ, Garside S, Dupras DM, Erwin PJ, Montori VM: Instructional design variations in internet-based learning for health professions education: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Med. 2010, 85: 909-922.

Bernard RM, Abrami PC, Lou Y, Borokhovski E, Wade A, Wozney L, Wallet PA, Fiset M, Huang B: How does distance education compare with classroom instruction? A meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Rev Ed Res. 2004, 74: 379-439.

Jwayyed S, Stiffler KA, Wilber ST, Southern A, Weigand J, Bare R, Gerson L: Technology-assisted education in graduate medical education: a review of the literature. Int J Emerg Med. 2011, 4: 51-

Issenberg SB, McGaghie WC, Petrusa ER, Gordon L, Scalese RJ: Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review. Med Teach. 2005, 27: 10-28.

Cook DA, Erwin PJ, Triola MM: Computerized virtual patients in health professions education: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Med. 2010, 85: 1589-1602.

Cooper H, Carlisle C, Gibbs T, Watkins C: Developing an evidence base for interdisciplinary learning: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2001, 35: 228-237.

Hammick M, Freeth D, Koppel I, Reeves S, Barr H: A best evidence systematic review of interprofessional education: BEME guide No. 9. Med Teach. 2007, 29: 735-751.

Reeves S, Zwarenstein M, Goldman J, Barr H, Freeth D, Hammick M, Koppel I: Interprofessional education: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008, 1: CD002213-

Zwarenstein M, Reeves S, Barr H, Hammick M, Koppel I, Atkins J: Interprofessional education: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001, 1: CD002213-

McNair R, Stone N, Sims J, Curtis C: Australian evidence for interprofessional education contributing to effective teamwork preparation and interest in rural practice. J Interprof Care. 2005, 19: 579-594.

Remington TL, Foulk MA, Williams BC: Evaluation of evidence for interprofessional education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006, 70: 66-

Cutcliffe JR, Bajkay R, Forster S, Small R, Travale R: Nurse migration in an increasingly interconnected world: the case for internationalization of regulation of nurses and nursing regulatory bodies. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2011, 25: 320-328.

Fealy GM, Carney M, Drennan J, Treacy M, Burke J, O’Connell D, Howley B, Clancy A, McHugh A, Patton D, Sheerin F: Models of initial training and pathways to registration: a selective review of policy in professional regulation. J Nurs Manag. 2009, 17: 730-738.

Buchan J, Dal Poz MR: Skill mix in the health care workforce: reviewing the evidence. Bull World Health Organ. 2002, 80: 575-580.

Boelen C, Wollard B: Social accountability and accreditation: a new frontier for educational institutions. Med Educ. 2009, 43: 887-894.

Pfister CA, Egger L, Wirthmüller B, Greif R: Structured training in introaseous infusion to improve potentially life saving skills in pediatric emergencies - Results of an open prospective national quality development project over 3 years. Paediatr Anaesth. 2008, 18: 223-229.

DeVito C, Nobile CG, Furnari G, Pavia M, De Giusti M, Angellilo IF, Villari P: Physician’s knowledge, attitudes and professional use of RCTs and meta-analyses: a cross-sectional survey. Eur J Public Health. 2009, 19: 297-302.

Grady K, Ameh C, Adegoke A, Kongnyuy E, Dornan J, Falconer T, Islam M, van den Broek N: Improving essential obstetric and newborn care in resource-poor countries. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011, 31: 18-23.

Ahmed C, Adegoke A, Hofman J, Ismail FM, Ahmed FM, van den Broek N: The impact of emergency obstetric care training in Somaliland, Somalia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012, 117: 283-287.

Mitchell DA, Lassiter SL: Addressing health care disparities and increasing workforce diversity: the next step for the dental, medical, and public health professions. Am J Pub Health. 2006, 96: 2093-2097.

Fauveau V, Sherratt DR, de Bernis L: Human resources for maternal health: multi-purpose or specialists?. Hum Resour Health. 2008, 6: 21-

Pawson R, Wong G, Owen L: Known knowns, known unknowns, unknown unknowns: the predicament of evidence-based policy. Am J Eval. 2011, 32: 518-546.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the contribution of the Jhpiego Concept Analysis Collaborating Group who provided guidance and review of this work: Linda Bartlett, PhD; Catherine Carr, DrPH; Amnesty Lefevre, PhD; Luc de Bernis, MD; Carey McCarthy, MPH; Lois Schaefer, MPH; Jeffrey Smith, MD; Udaya Thomas, MSN, MPH; Tegbar Yigzaw, MD; and Barbara Rawlins, MPH.

We also thank Lori Ronsman, Librarian, Johns Hopkins University, for generating the literature search, and Jessica Alderman, MPH, for her assistance with data abstraction.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Authors contributed equally to the review of the literature and development of the manuscript and conceptual model. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Peter Johnson, Linda Fogarty, Judith Fullerton, Julia Bluestone and Mary Drake contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Johnson, P., Fogarty, L., Fullerton, J. et al. An integrative review and evidence-based conceptual model of the essential components of pre-service education. Hum Resour Health 11, 42 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-11-42

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-11-42