Abstract

Background

Suppression of immune system in treated cancer patients may lead to secondary infections that obviate the need of antibiotics. In the present study, an attempt was made to understand the occurrence of secondary infections in immuno-suppressed patients along with herbal control of these infections with the following objectives to: (a) isolate the microbial species from the treated oral cancer patients along with the estimation of absolute neutrophile counts of patients (b) assess the in vitro antimicrobial activity medicinal plants against the above clinical isolates.

Methods

Blood and oral swab cultures were taken from 40 oral cancer patients undergoing treatment in the radiotherapy unit of Regional Cancer Institute, Pt. B.D.S. Health University,

Rohtak, Haryana. Clinical isolates were identified by following general microbiological, staining and biochemical methods. The absolute neutrophile counts were done by following the standard methods. The medicinal plants selected for antimicrobial activity analysis were Asphodelus tenuifolius Cav., Asparagus racemosus Willd., Balanites aegyptiaca L., Cestrum diurnum L., Cordia dichotoma G. Forst, Eclipta alba L., Murraya koenigii (L.) Spreng. , Pedalium murex L., Ricinus communis L. and Trigonella foenum graecum L. The antimicrobial efficacy of medicinal plants was evaluated by modified Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method. MIC and MFC were investigated by serial two fold microbroth dilution method.

Results

Prevalent bacterial pathogens isolated were Staphylococcus aureus (23.2%), Escherichia coli (15.62%), Staphylococcus epidermidis (12.5%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (9.37%), Klebsiella pneumonia (7.81%), Proteus mirabilis (3.6%), Proteus vulgaris (4.2%) and the fungal pathogens were Candida albicans (14.6%), Aspergillus fumigatus (9.37%). Out of 40 cases, 35 (87.5%) were observed as neutropenic. Eight medicinal plants (A. tenuifolius, A. racemosus, B. aegyptiaca, E. alba, M. koenigii, P. murex R. communis and T. foenum graecum) showed significant antimicrobial activity (P < .05) against most of the isolates. The MIC and MFC values were ranged from 31 to 500 μg/ml. P. aeruginosa was observed highest susceptible bacteria (46.6%) on the basis of susceptible index.

Conclusion

It can be concluded that treated oral cancer patients were neutropenic and prone to secondary infection of microbes. The medicinal plant can prove as effective antimicrobial agent to check the secondary infections in treated cancer patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Over the past decade, advances in the cancer treatment field have been counterbalanced by a rising number of immunosuppressed patients with a multitude of new risk factors for infection [1]. Cancer patients may be immunocompromised due to multiple factors such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, impairment of normal leukocyte function, or use of corticosteroids [2]. As well as the infections complications remain an important cause of mortality and morbidity between these febrile neutropenic cancer cases [3, 4]. They are highly susceptible to almost any type of infection, especially bacterial and fungal infection [5].

Same side the heavy antimicrobial usage particularly in high-risk cancer patients create selection pressures that lead to the emergence of resistant micro-organisms [6]. For instance, many cancer centers have reported an increase in quinolone resistant bacteria (primarily Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa) in patients receiving quinolone prophylaxis [6–8]. The use of very broad spectrum agents such as the carbapenems has been associated with the selection of multidrug-resistant (MDR) in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia and Pseudomonas aeruginosa[9–11]. Therefore the increase in antibiotic resistance activity is posing an ever increasing therapeutic problem in cancer case and the ways by which bacteria overcome drug action are many and varied, ranging from intrinsic impermeability to acquired resistance [12–14]. In light of the evidence of rapid spread of resistant clinical isolates, the need to find new antimicrobial agent is of paramount importance for the treatment of infectious diseases in cancer cases.

Researchers are increasingly turning their attention to the medicinal plants and it is estimated that, plant materials are present in, or have provided the models for 25- 50% Western drugs [15, 16]. Many commercially proven drugs used in modern medicine was initially used in crude form in traditional or folk healing practices, or for other purposes that suggested potentially useful biological activity. Because the primary benefits of using plant derived medicines are that they are relatively safer than synthetic alternatives, offering profound therapeutic benefits and more affordable treatment [17]. As well as the scarcity of infective disease in wild plants is in itself an indication of the successful defense mechanism developed by them. The defenses mechanisms of the plants may be due to production of enormous variety of small molecules generally classified as 'Phytoalexins'. Phytoalexins are "low molecular weight (MW < 500), anti-microbial compounds that are both synthesized and accumulated in plants after exposure to microorganisms or abiotic agents". Phytoalexins structural spaces contain terpenoids, glycosteroids, flavonoids and polyphenols and these biologically active compounds supposed to exhibit antimicrobial properties [18–20].

Since time immemorial, the traditional medicinal practices have been known for the treatment of various ailments in India. The medicinal plants were selected in this study based on their common uses in Indian traditional systems of medicine [21–27]. Keeping in view, the infectious diseases in oral cancer patients it was important to investigate whether the Indian indigenous plants have any antimicrobial activity against clinical isolates of oral cancer cases. So the present investigation evaluates the infection in immunocompromised oral cancer cases and in vitro antimicrobial activity of crude extracts of ten medicinal plants (Asphodelus tenuifolius Cav., Asparagus racemosus Willd., Balanites aegyptiaca L., Cestrum diurnum L., Cordia dichotoma G. Forst, Eclipta alba L., Murraya koenigii (L.) Spreng., Pedalium murex L., Ricinus communis L. and Trigonella foenum graecum L.) against these clinical isolates.

Materials and methods

Blood and oral swab cultures were taken from 40 oral cancer patients undergoing treatment in the radiotherapy unit of Regional Cancer Institute, Pt. B.D.S. Health University, Rohtak, Haryana (September 2008 to September 2009). These patients were under different treatment protocol i.e., radiotherapy, chemotherapy and radio-chemotherapy both together. The present study was approved by Institutional Human Ethics Committee of the university (M.D. University, Rohtak) and written consent was also taken from the patients. The blood samples (5 ml) were collected from central venous catheter and peripheral vein of the patients at the onset of fever (before the prescription of antibiotics). Blood samples were then transferred in culture bottles of brain heart infusion broth (Hi Media, Mumbai, India). Bottles were incubated at 36.7°C for 7 days. Bottles showing positive growth index were Gram stained and sub cultured on sheep blood agar, sabourad dextrose agar, MacConkey agar and on nutrient agar plates all media were taken from Hi Media, Mumbai, India. These plates were aerobically incubated for 24-48 h at 37°C for isolation of bacterial pathogens and for 24-72 h at 30°C in B.O.D. incubator for fungal pathogenic species isolation. Oral swab were taken by gently rubbing a sterile cotton swab over the labial mucosa, tongue and cancerous lesion [28]. Oral swab were taken at the onset of fever (before the prescription of antibiotics). The swabs were incubated in sheep blood agar, saboured dextrose agar, macconkey agar, nutrient agar, and other selective media for primary isolation of the pathogens. These plates were then aerobically incubated for 24-48 h at 37°C for bacterial pathogens isolation and for 24-72 h at 30°C in B.O.D. incubator for fungal species isolation. When growth was appeared on sub cultured plates of blood and oral swab, all bacterial pathogens were identified by standard microbiological and biochemical procedures. These biochemical tests include carbohydrates fermentation test, urease test, oxidase test, haemolysis of blood, catalase test, motility test and growth of pathogens on specific media etc. [29–32]. A preliminary examination of fungal colony on SDA was done through Gram-stained smear, formation of germ tube, study of micro morphology, morphology on KOH stained smear, assimilation of carbon and nitrogen [29–32]. All isolated pathogens were compared with MTCC standard strains like S. aureus with MTCC 96 strain, S. epidermidis MTCC 435 strain, P. vulgaris MTCC 426 strain, P. mirabilis MTCC 425 strain, E. coli MTCC 443 strain, K. pneumonia MTCC 109 strain, P. aeruginosa MTCC 741 strain, C. albicans 3017 strain and A. fumigatus 2550 strain respectively.

Absolute neutrophile count

The absolute neutrophile count (ANC) was done by multiplying the total WBC count by percentage of neutrophils (segmented + band) [5].

Neutropenia: When ANC was less than 500 (sever risk of infection).

Non neutropenia: When ANC was more than 500 (moderate risk of infection).

Collection of Plant Material

The fruits of A. tenuifolius, fresh tubers of A. racemosus, mature fruits of B. aegyptiaca, aerial part of C. diurnum, mature fruits of C. dichotoma, whole plant of E. alba, mature fruits P. murex, leaves of M. koenigii, seeds of R. communis and leaves of T. foenum graecum were collected (October 2008 to December 2009) from different regions of Haryana. The collected plants were identified in the laboratory. Comparison of flora was also made according to different references concerning with the medicinal plants of Haryana and adjoining areas [33–36]. The voucher specimens were deposited in the herbarium of Genetics Department, M. D. University, Rohtak.

All plant parts were dried at room temperature. The dried parts were pounded to fine powder and extracted in different solvents according to their increasing polarity (Petroleum ether, benzene, chloroform, acetone, methanol and aqueous) for 24 h in Soxhlet apparatus. The solvents were recovered with the help of rotary evaporator at 40°C. The quantity of obtained dried plant material varies from 100 gm to 500 gm. The dried extracts were lyophilized in lypholyser. The lyophilized extracts were stored in air tight tubes at 4°C for further anti-microbial analysis.

Assay for antimicrobial testing

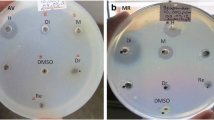

Isolated test bacteria were grown overnight on nutrient agar plates and fungi were grown on sabouraud dextrose agar plates. Bacterial inoculums were prepared from overnight grown cultures (24 h) in peptone water (Hi Media, Mumbai, India), and the turbidity was adjusted equivalent to 0.5 McFarland units (approximately 108 CFU/ml for bacteria and fungi inoculums turbidity was equivalent at 105 or 106 CFU/ml). The microorganisms were inoculated into peptone water and incubated at 35 ± 2°C for 4 h. The positive control was taken streptomycin (10 μg/ml) for antibacterial activity and ketocanozole (10 μg/ml) for antifungal activity. The DMSO added disc was taken as negative control to determine possible inhibitory activity of the dilutant of extract. The susceptibilities of the isolated pathogens were determined by the modified Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method with Muller Hinton agar plates [37]. Aliquots of inoculums were spread over the surface of agar plates with a sterile glass spreader. To test the antimicrobial activity all extracts were dissolved in DMSO to make a final concentration of 200 mg/ml. 20 μl of each extract was soaked separately into sterile discs (Hi Media, Mumbai, India), and the discs were dried in oven for 4 hours at 35°C. These discs were placed on Muller Hinton agar plates, previously swabbed with the bacterial and fungal inoculum. These plates were incubated for a period of 24 h at 37°C in incubator for bacteria and at 30°C for 24-48 h in B.O.D incubator for fungi. Each experiment was done in triplicate and mean values were taken. Antimicrobial activity was measured in the diameter (mm) of the clear inhibitory zone formed around the disc.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and Minimum fungicidal concentration (MFC)

The MIC and MFC values of extracts were determined based on a microbroth dilution method in 96 multi-well microtitre plates with slight modifications [38]. The crude plant extracts were first diluted to the highest concentration, 40000 to 625 μg/ml), to be tested, and 50 μl of normal saline was distributed from the second to the ninth well. A volume of 50 μl from each extracts was pipetted into the first test well of each microtitre line which acts as sterility control, and then 50 μl of scalar dilution of plant extract was transferred from the second to the ninth well. To each well was added 10 μl of resazurin indicator solution (prepared by dissolving a 270 mg tablet in 40 ml of sterile distilled water). Using a pipette 30 μl of Muller Hinton broth was added to each well to ensure that the final volume was of single strength of the normal saline. Finally, 10 μl of the bacterial suspensions were added to each well. In each plate, a column with a broad-spectrum antibiotic was used as the positive control (streptomycin in serial dilution 40000 to 625 μg/ml).

The plates were wrapped loosely with cling film to ensure that bacterium did not become dehydrated, and were prepared in triplicate. Subsequently, they were placed in an incubator at 37°C for 24 h. Any color change from purple to pink or to colorless was recorded as positive.

The lowest concentration at which the color change occurred was taken as the MIC and MFC value. The average of three values was calculated to determine the MIC and MFC of the test material.

Preliminary phytochemical analysis

The qualitative preliminary phytochemical analyses of the crude extracts of all plants part isolated from different solvents were performed by following standard methods [39, 40].

Statistical analysis

Each parameter was tested in triplicate. The values were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The Dunnett one way analysis (ANOVA) was used to determine the significant differences among all columns against control and the P value < .05 was considered as significant. All statistical analysis was performed using Graph Pad Prism version 5.03 software.

Quantitative evaluation of antimicrobial activity

% of extractive value:

Percent activity: The percent activity demonstrates the total anti- microbial potency of particular extract. It shows number of microbes found susceptible to one particular extract [41].

Bacterial susceptible index (BSI): BSI is used to compare the relative susceptibility between bacterial strains. BSI valves ranges from 0 (resistance to all samples) to 100 (susceptible to all extract [41].

Results

In the present study the predominant bacterial pathogens isolated were Staphylococcus aureus (23.2%), Escherichia coli (15.62%), Staphylococcus epidermidis (12.5%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (9.37%), Klebsiella pneumonia (7.81%), Proteus mirabilis (3.6%), Proteus vulgaris (4.2%) and the fungal pathogens were Candida albicans (14.6%), Aspergillus fumigatus (9.37%). On the basis of absolute neutrophile count it was observed that out of 40 cases, 35 (87.5%) were neutropenic. The extracts of ten medicinal plants were prepared in the petroleum ether, benzene, chloroform, acetone, methanol, water and were screened against nine isolates (7 bacterial and 2 fungal sp.). The details of the plants along with their voucher number, family name, common name, parts used, traditional uses and literature source have been listed in Table 1. The phytochemicals isolated from ten medicinal plants were containing alkaloids, amino acids, anthraquinones, cardiac glycosides, flavonoids, reducing sugars, resins, saponins, steroids, terpenes, tannins, proteins, phenols and steroids as shown in Table 1.

In the present study the percentage extractive values were ranged from .05 to 17%. The % extractive value and yield of extracts was found maximum in methanol and aqueous extract due to their high polarity and easy solubility of secondary metabolites in the methanol and water. The antimicrobial activity of different plant extract has been listed in Table 2.

The antimicrobial activity different extracts of A. tenuifolius, A. racemosus, B. aegyptiaca, C. diurnum, C. dichotoma, E. alba, P. murex, M. koenigii, R. communis and T. foenum graecum on different bacterial and fungal clinical isolates has been shown Table 2 as mean ± SE. S. aureus exhibited good susceptibility to acetone extract of A. tenuifolius, A. racemosus, C. dichotoma, M. koenigii and P. murex. S. epidermidis exhibited remarkable susceptibility to all solvent extract (except acetone) of B. aegyptiaca. Pet. ether, benzene and chloroform extracts of B. aegyptiaca and T. foenum graecum revealed significant antibacterial activity against P. vulgaris. Our study revealed P. mirabilis as most resistance bacterial species due very limited activity observed in all plant extracts. Out of six solvents, benzene extract of A. tenuifolius, A. racemosus, E. alba, P. murex R. communis and T. foenum graecum exhibited good antibacterial activity against P. mirabilis. Like P. mirabilis, E. coli also found susceptible to benzene extract of A. racemosus, E. alba, P. murex and T. foenum graecum. The benzene extracts of A. racemosus, A. tenuifolius, B. aegyptiaca, E. alba, P. murex, R. communis and T. foenum graecum also exhibit very good susceptibility to K. pneumonia. P. aeruginosa which is considered as very resistance species in infectious diseases was observed 100% susceptible to all solvent extracts of R. communis. Out of selected medicinal plants A. racemosus exhibited good antifungal activity against C. albicans. A. fumigatus was found resistant to B. aegyptiaca, C. diurnum, C. dichotoma, E. alba, M. koenigii, R. communis and T. foenum graecum extracts.

In our study the percent activity i.e the total anti- microbial potency of particular extract was evaluated from 14.2 to 100%. The acetone extract of A. racemosus and the Pet. ether of T. foenum graecum showed 100% activity to all clinical isolates. The present study also revealed that the P. aeruginosa was highest susceptible bacteria with 46.6%% susceptibility followed by K. pneumonia (40%), S. epidermidis (35%), S. aureus (30%), E. coli (30%), P. vulgaris (26.6%) and P. mirabilis (20%).

The MIC and MFC of different solvent extracts against clinical isolates has been listed in Table 3. The MIC ranges from 31 to 500 μg/ml and similarly the MFC ranges from 31 to 500 μg/ml. The minimum MIC (31 μg/ml) of all extracts was observed in the following way, the acetone extract of A. racemosus against P. vulgaris and K. pneumonia, the methanolic extract of B. aegyptiaca and R. communis against K. pneumonia, the aqueous extract of R. communis against P. aeruginosa, aqueous and methanolic extract of T. foenum- graecum against P. aeruginosa.

But on the other hand the minimum MFC (31 μg/ml) was exhibited in acetone extract of A. racemosus against A. fumigatus. The potency of the extract based on the zones of inhibitions, was compared with standard commercial available antibiotics such as streptomycin (10 μg/ml) and ketacanzole at (10 μg/ml) observed that the antimicrobial activity of crude extracts was less than those of the standard drugs.

Discussion

Patients with cancer develop serious bacterial and fungal infections often, especially during periods of cancer treatments. Antibiotic usage for the prevention and treatment of bacterial infections in these high-risk patients leads to selection pressures resulting in the emergence and spread of resistant organisms. Many organisms acquire several resistances mechanisms; making them multi-drug-resistant (MDR). The development of novel antimicrobial agents with activity against pathogens that have become resistant to currently available agents is one tactics for combating resistant organisms [42]. Therefore the rapid propagation in antibiotic resistance and the increasing interest in natural products have placed medicinal plants back in the front lights as a reliable source for the discovery of active anti-microbial agents and possibly even novel classes of antibiotics [43]. So in keeping view all the use of medicinal plants our study was based on isolation of microbes of oral cancer patients and antimicrobial activity of medicinal plants against these clinical isolates.

In the present study we found that seeds extract of A. tenuifolius, the tuber extracts of A. racemosus, fruit extract of B. aegyptiaca, leaves extract of T. foenum- graecum, showed antibacterial activity against most of the isolated microbes from the oral cancer cases. The significant antifungal activity was exhibited by different extracts of A. racemosus (P < .05) against C. albicans but in contrast to that no significant antifungal activity was observed against A. fumigatus.

Although numerous studies have in the past, focused on antimicrobial activity of A. racemosus, A. tenuifolius, B. aegyptiaca, E. alba, P. murex, R. communis and T. foenum graecum against various bacteria and fungi [27, 44–46] but very few studies have been focused on the antimicrobial activity of these medicinal plants against clinical isolates.

Methanol and water extracts of A. racemosus tubers were screened against E. coli. S. aureus, K. pneumonia, P. aeruginosa and C. albicans obtained from R.N.T. Medical College, Udaipur (Rajasthan). Antimicrobial activity was observed against all the studied microbes with inhibition zone range from 7 to 24 mm [47]. On the contrary we have not observed antibacterial activity against E. coli, S. aureus, K. pneumonia and P. aeruginosa. Another study the showed the antifungal activity of tubers methanol extract against C. albicans (16 mm) isolated from vaginal thrush patients, visiting Rajah Muthiah Medical College and Hospital, Annamalai Nagar, Tamilnadu, India [48]. Our study revealed the almost similar antifungal activity of A. racemosus tubers against C. albicans (13 mm).

The methanol and ethanol leaf extracts of E. alba was evaluated for the antimicrobial activity against human isolated pathogens (E. coil, K. pneumonia, S. aureus and P. aeruginosa ) obtained from Department Microbiology, Mysore Medical College and Research Institute, Rajiv Gandhi University, Mysore, India [49]. It was observed that both extracts exhibited antibacterial activity against all bacteria and inhibition zone was observed ranged from 9 to 20 mm. But in contrast to above study we found that methanol and aqueous extract of E. alba have no inhibition against E. coli, K. pneumonia and S. aureus but activity was only found against P. aeruginosa (10 mm, 11 mm).

To a large extent, the chronological age of the plant, percentage humidity of the harvested material, situation and time of harvest, solvent used and the method of extraction were possible sources of variation for the bioactivity of the extracts [50–52].

As it is well known that P. aeruginosa is notorious for its resistance to antibiotics and is, therefore particularly dangerous and dreaded pathogen. The bacterium is naturally resistance to many antibiotics due to the permeability barriers afforded by its outer membrane composed of lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Also, its tendency to colonize surfaces in a biofilm form makes the cells impervious to therapeutic concentrations of antibiotics. One method to reduce the resistance to antibiotics is by using antibiotics resistance inhibitors from plant origin [53, 54]. We have observed very significant (P < .05) antibacterial activity of B. aegyptiaca and R. communis all extracts, against P. aeruginosa. These results revealed that the antibacterial activity of R. communis and B. aegyptiaca extracts hold the most promise for further work against this bacterium through toxicity testing.

In our study various phytochemicals compounds alkaloids, amino acids, anthraquinones, cardiac glycosides, flavonoids, reducing agents, resins, saponins, terpenes, tannins, proteins, phenols and steroids were isolated from ten medicinal plants. The antimicrobial susceptibility of studied medicinal plants could be attributed to the presence of these antimicrobial compounds, which is also proved by other studies [55–62].

The results of our research highlights, the fact that the organic solvent extracts exhibited greater antimicrobial activity because the antimicrobial principles were either polar or non-polar and they were extracted only through the organic solvent medium [63, 64]. So the present observation suggests that the organic solvent extraction was suitable to verify the antimicrobial properties of medicinal plants which are also supported by many other investigators [65–68].

In nut shell, our study justifies the claimed uses of A. tenuifolius, A. racemosus, B. aegyptiaca, E. alba, P. murex, M. koenigii, R. communis and T. foenum graecum in the Indian traditional system of medicine to treat various diseases. However, as the toxic affects of plant extracts were not explored or tested in present study, so the usefulness of these extracts as antimicrobial compound can only be predicated after toxicity testing on eukaryotic cells.

Conclusion

The present investigation reported that the secondary infections in the immunocompromised oral cancer cases were due to bacterial and fungal species. This study also report that the medicinal plants (A. tenuifolius, A. racemosus, B. aegyptiaca, E. alba, P. murex, M. koenigii, R. communis and T. foenum graecum) used in Indian-herbal medicine may possess antimicrobial activity against the clinical isolates of oral cancer cases. These findings can form the basis for further studies to toxicity testing, isolate active compounds, elucidate the structures, and also evaluate them against wider range of resistance bacterial and fungal strains of cancer patients with the goal to find new therapeutic principles.

References

Klastersky J: Management of fever in neutropenic patients with different risks of complications. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2004, 39 (Suppl 1): S32--7.

Klastersky J, Paesmans M, Rubenstein E: The MASCC Risk Index: a multinational scoring system to predict low-risk febrile neutropenic cancer patients. Journal Clinical Oncology. 2000, 18: 3038-51.

Rolston KVI: Challenges in the treatment of infections caused by gram-positive and gram- negative bacteria in patients with cancer and neutropenia. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2005, 40: S246-S252. 10.1086/427331

Akova M: Emerging problem pathogens: A review of resistance patterns over time. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2006, 10 (S2): S3-S8.

Hughes WT, Armstrong D, Bodey GP: Guidelines for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2002, 34: 730-51. 10.1086/339215

Rolston KV, Jones RN, Coyle EA, Prince RA: Emergence of quinolone resistant Escherichia coli at a cancer center [abstract]. 2007, 506-45th Annual Meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), San Diego, CA

Gomez L, Garau J, Estrada C, Marquez M, Dalmau D, Xercavins M, Marti JM, Estany C: Ciprofloxacin prophylaxis in patients with acute leukemia and granulocytopenia in an area with a high prevalence of ciprofloxacin- resistant Escherichia coli. Cancer. 2003, 97: 419-424. 10.1002/cncr.11044

Cattaneo C, Quaresmini G, Casari S, Capucci MA, Micheletti M, Borlenghi E, Signorini L, Re A, Carosi G, Rossi G: Recent changes in bacterial epidemiology and the emergence of fluoroquinolone resistant Escherichia coli among patients with haematological malignancies: results of a prospective study on 823 patients at a single institution. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2008, 61: 721-728. 10.1093/jac/dkm514

Toleman MA, Rolston K, Jones RN, Walsh TR: Molecular and biochemical characterization of OXA-45, an extended-spectrum class 2d', ß-lactamase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrobial Agents Chemotherapy. 2003, 47: 2859-2863. 10.1128/AAC.47.9.2859-2863.2003.

Ohmagari N, Hanna H, Graviss L: Risk factors for infections with multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in patients with cancer. Cancer. 2005, 104: 205-212. 10.1002/cncr.21115

Safdar A, Rolston KV: Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: changing spectrum of a serious bacterial pathogen in patients with cancer. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2007, 45: 1602-1609. 2007, 10.1086/522998

Green M, Wald ER: Emerging resistance to antibiotics: impact on respiratory infections in the outpatient setting. Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. 1996, 77: 167-173. 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)63250-4.

Williams JD, Sefton AM: The prevention of antibiotic resistance during treatment. Infection. 1999, 2: 29-31.

Rice LB: Successful interventions for gram-negative resistance to extended-spectrum beta-lactam antibiotics. Pharmacotherapy. 1999, 19: 120-128. 10.1592/phco.19.12.120S.31699.

Khan R, Islam B, Akram M, Shakil S, Ahmad A, Ali SM, Siddiqui M, Khan AU: Antimicrobial activity of five herbal extracts against Multi Drug Resistant (MDR) strains of bacteria and fungus of clinical origin. Molecules. 2009, 14: 586-597. 10.3390/molecules14020586

Robbers J, Speedie M, Tyler V: Pharmacognosy and pharmacobiotechnology. 1996, Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore

Daciana I, Bara II: Plant products as antimicrobial agents. Analele Stiinţifice ale Universitaţii Alexandru Ioan Cuza Secţiunea Genetica si Biologie Moleculara. 2007, VIII-TOM

Paxton JD: Phytoalexins a working redefinition. Phytopathology. 1980, 132: 1-45.

VanEtten HD, Mansfield JW, Bailey J, Farmer EE: Letter to the editor: two classes of plant antibiotics: phytoalexins versus phytoanticipins. Plant Cell. 1994, 6: 1191-1192

Hemaiswarya S, Kruthiventi AK, Doble M: Synergism between natural products and antibiotics against infectious diseases. Phytomedicine. 2008, 15: 639-652. 10.1016/j.phymed.2008.06.008

Chopra RN: Indigenous Drugs of India. 1958, Revised and Enlarged by Chopra R N, Chopra, IC, Handa KL and Kapur LD, Dhur and Sons Private Limited., Calcutta, 2

Kirtikar KR, Basu BD: Indian medicinal plants. 1968, I: Allhabad, India: Lalit Mohan Basu publisher and distributor

Nadkarani KM: Indian Material Medica. 1982, II: Mumbai: Popular Prakashan private limited

Satavat GV, Gupta AK: Medicinal plants of India. 1987, II: New Delhi: ICMR

Nadkarani KM: Indian Material Medica. 1989, III: Mumbai: Popular Prakashan Private Limited

Chopra RN, Nayer SI, Chopra IC: Glossary of Indian medicinal plants. 1992, 7-246. New Delhi: Council of scientific and Industrial Research, 3

Ahmad I, Mehmood Z, Mohammad F: Screening of some Indian medicinal plants for their antimicrobial properties. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1998, 62: 183-193. 10.1016/S0378-8741(98)00055-5

Rautemaa R, Rusanen P, Richardson M, Meurma JH: Optimal sampling site for mucosal candidosis in oral cancer patients is the labial sulcus. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2006, 55: 1447-1451. 10.1099/jmm.0.46615-0

Shimeld LA: Essential of Diagnostic Microbiology. 1998, International Thomas Publishing Company, USA

Hawkey P, Law D: Medical Bacteriology. 2004, Oxford University Press, New York, 2

Ryan KJ: Normal Microbial flora. Medical Microbiology. Edited by: Sherris JC, Ryan KJ, Ray GC. 2004, McGraw Hill, USA, Fourth

Mukherjee KL: A procedure manual for routine diagnostic test. Edited by: Tata Mac. 2006, II: Grew Hill publishing compd. Limited

Bhandari MM: Flora of the Indian Desert. 1990, Scientific Publishers, Jodhapur

Kumar S: Flora of Haryana. 2001, Publishers Bishen S, Mahendra PS, New Delhi

Sharma N: The Flora of Rajasthan. 2002, 280-Aavishkar Publishers, Jaipur

Sharma NK: Ethno-medico-Religious plants of Hadoti plateau (S. E. Rajasthan)-a preliminary survey. Ethnobotany. Edited by: Trivedi PC. 2002, Aaviskar Publishers, Jaipur

Bauer AW, Kirby WMM, Sheriss JC, Turc M: Antibiotic susceptibility testing by standardized single method. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1996, 45: 493-496.

Sarker SD, Nahar L, Kumarasamy Y: Microtitre plate-based antibacterial assay incorporating resazurin as an indicator of cell growth, and its application in the in vitro antibacterial screening of phytochemicals. Methods. 2007, 42: 321-324. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.01.006

Harborn JB: Phytochemical Methods, A guide to modern Techniques of plant analysis. 1988, London: Chapman and Hall Limited

Kokate CK: Practical pharmacognosy. 2005, 107-Published by Jain MK for Vallabh Prakashan, Pitampura, New Delhi

Bonjar GHS: Approaches in screening for antibacterial in plants. Asian Journal of Plant sciences. 2004, 31 (1): 55-60.

Kenneth VIR: New antimicrobial agents for the treatment of bacterial infections in cancer patients. Hematological Oncology. 2009, 27: 107-114. 10.1002/hon.898

Schultes RE: Tapping our heritage of ethnobotanical lore. Economic Botany. 1960, 14: 257-262. 10.1007/BF02908034.

Valsaraj R, Pushpangadan P, Smitt UW, Adsersen A, Nyman U: Antimicrobial screening of selected medicinal plants from India. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1997, 58: 75-83. 10.1016/S0378-8741(97)00085-8

Khafagy SM, Ishrak K: Screening culture of some Sinani medicinal plants for their antibiotic activity. Egyptian Journal of Microbiology. 1999, 34 (4): 613-627.

Mandal SC, Nandy A, Pal M, Saha BP: Evaluation of Antibacterial activity of Asparagus racemosus willd. Root. Phytotherapy Research. 2000, 14: 118-119. 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1573(200003)14:2<118::AID-PTR493>3.0.CO;2-P

Swarnkar S, Katewa SS: Antimicrobial activities of some tuberous medicinal plants from aravalli hills of Rajasthan. Journal of Herbal Medicine and Toxicology. 2009, 3 (1): 53-58.

Uma B, Prabhakar K, Rajendra S: Anticandidal activity of Asparagus racemosus. Indian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2009, 71 (3): 342-343. 2009, 10.4103/0250-474X.56017

Girish HV, Satish S: Antibacterial Activity of Important Medicinal Plants on Human Pathogenic Bacteria-a Comparative Analysis. World Applied Sciences Journal. 2008, 5 (3): 267-271.

Felix MT: Medical Microbiology. 1982, Churchill Livingstone (Publishers): London, UK

Eloff JN: Which extractant should be used for the screening of antimicrobials components from plants?. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1998, 60: 1-8. 10.1016/S0378-8741(97)00123-2

Nimri LF, Meqdam MM, Alkofahi A: Antibacterial activity of Jordanian medicinal plants. Pharmaceutical Biology. 1999, 37 (3): 196-201. 10.1076/phbi.37.3.196.6308.

Iinuma M, Tsuchiya H, Sato M, Yokoyama J, Ohyama M, Ohkawa Y, Tanaka T, Fujiwara S, Fujii T: Flavanones with potent antibacterial activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of Pharmaceutical Pharmacology. 1994, 46: 892-895. 1994,

Kim H, Park SW, Park JM, Moon KH, Lee CK: Screening and isolation of antibiotic resistant inhibitors from herb materials I -- Resistant Inhibition of 21 Korean Plants. Natural Product Science. 1995, 1: 50-54.

Ahmed AA, Mahmoud AA, Williams HJ, Scott AI, Reibenspies JH, Mabry TJ: New sesquiterpene a-methylene lactones from the Egyptian plant Jasonia candicans. Journal Natural Products. 1993, 56: 1276-1280. 10.1021/np50098a011.

Batista O, Duarte A, Nascimento J, Simones MF: Structure and antimicrobial activity of diterpenes from the roots of Plectranthus hereroensis. Journal Natural Products. 1994, 57: 858-861. 10.1021/np50108a031.

Tsuchiya H, Sato M, Miyazaki T, Fujiwara S, Tanigaki S, Ohyama M, Tanaka T, Iinuma M: Comparative study on the antibacterial activity of phytochemical flavanones against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1996, 50: 27-34. 10.1016/0378-8741(96)85514-0

Rabe T, Van Stadin VJ: Antibacterial of South African plants used for medicinal purposes. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1997, 56: 81-87. 10.1016/S0378-8741(96)01515-2

Barre JT, Bowden BF, Coll JC, Jesus J, Fuente VE, Janairo GC, Ragasa CY: A bioactive triterpene from Lantana camara. Phytochemistry. 1997, 45: 321-324. 10.1016/S0031-9422(96)00805-9

Amaral JA, Ekins A, Richards SR, Knowles R: Effect of selected monoterpenes on methane oxidation, denitrification, and aerobic metabolism by bacteria in pure culture. Applied Environmental Microbiology. 1998, 64: 520-525.

Cowan CC: Plant Products as Antimicrobial Agents. Clinical Microbiology Review. 1999, 12 (4): 564-582.

Santhi R, Alagesaboopathi C, Pandian MR: Antibacterial activity of Andrographis lineata Nees and Andrographis echioides Nees of Shevaroy hills of Salem District, Tamil Naidu. Advance concepts in Plant Sciences. 2006, 19 (II): 371-375.

Mohanasundari C, Natarajan D, Srinivasan K, Umamaheswari SA, Ramachandran A: Antibacterial properties of Passiflora foetida L. -a common exotic medicinal plant. African Journal Biotechnology. 2007, 6 (23): 2650-2653.

Britto JS: Comparative antibacterial activity study of Solanum incanum L. Journal Swamy Botany Club. 2001, 18: 81-82.

Krishna KT, Ranjini CE, Sasidharan VK: Antibacterial and antifungal activity of secondary metabolites from some medicinal and other common plant species. Journal Life Sciences. 1997, 2: 14-19.

Singh I, Singh VP: Antifungal properties of aqueous and organic solution extracts of seed plants against Aspergillus flavus and A. niger. Phytomorphol. 2000, 50: 151-157. 2000,

Natarajan E, Senthilkumar S, Xavier FT, Kalaiselvi V: Antibacterial activities of leaf extracts of Alangium salviifolium. Journal Tropical Medicinal Plants. 2003, 4: 9-13.

Natarajan D, Britto JS, Srinivasan K, Nagamurugan N, Mohanasundari C, Perumal G: Anti-bacterial activity of Euphorbia fusiformis- a rare medicinal herb. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2005, 102: 123-126. 10.1016/j.jep.2005.04.023

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the M.D. University, Rohtak for providing the fellowships to Ms. Manju Panghal for this research work. We are also thankful to Haryana state government for providing us financial grants for necessary facilities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

All authors have equal contribution in study designs, experiment, data analysis and interpretation of data. Similarly all authors have critically reviewed the manuscript, approved of its contents and consented to its communication for publication

Manju Panghal, Vivek Kaushal and Jaya P Yadav contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Panghal, M., Kaushal, V. & Yadav, J.P. In vitro antimicrobial activity of ten medicinal plants against clinical isolates of oral cancer cases. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 10, 21 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-0711-10-21

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-0711-10-21