Abstract

Background

Between 2% and 5% of malignant germ-cell tumors in men arise at extragonadal sites. Of extragonadal germ cell tumors, testicular carcinoma in situ (CIS) are present in 31–42% of cases, and CIS are reported to have low sensitivity to chemotherapy in spite of the various morphology and to have a high likelihood of developing into testicular tumors. A testicular biopsy may thus be highly advisable when evaluating an extragonadal germ cell tumor.

Case presentation

A 36-year-old man was diagnosed as having an extragonadal non-seminomatous germ cell tumor, that was treated by cisplatin-based chemotherapy, leading to a complete remission. In the meantime, testicular tumors were not detected by means of ultrasonography. About 4 years later, a right testicular tumor was found, and orchiectomy was carried out. Microscopically, the tumor was composed of seminoma.

Conclusions

We herein report a case of metachronous occurrence of an extragonadal and gonadal germ cell tumor. In the evaluation of an extragonadal germ cell tumor, a histological examination should be included since ultrasonography is not sufficient to detect CIS or minute lesions of the testis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Between 2% and 5% of malignant germ-cell tumors in men arise at extragonadal sites [1]. Cytogenetically most extragonadal germ-cell tumors (EGGCTs) i.e., the seminomas and non-seminomas, are similar to their testicular counterparts [2, 3]. But there are CIS in 31–42% of EGGCT patients' testes [4]. Ultrastructural studies indicate that CIS originate from rather primitive cells and can develop into different categories of germ cell carcinomas. Furthermore, since CIS are reported to respond poorly to chemotherapies, a metachronous development of testicular cancer will possibly occur, in spite of the various morphologies of testicular cancer [5, 6]. In the present case, the etiology of a metachronous appearance of EGGCT and testicular cancer is discussed.

Case presentation

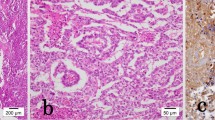

A 36-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with the chief complaint of right-sided scrotal enlargement. He had previously received treatment for an extragonadal germ cell tumor. At the age of 32, he presented with lumbago. CT showed a retroperitoneal tumor (Figure 1), and a transabdominal needle biopsy was carried out. Microscopically, the tumor was composed of a yolk sac tumor (Figure 2A,2B). We performed two courses of systemic chemotherapy using bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin, leading to a partial response. As the tumor size was not seemed to decrease after the two courses of the chemotherapy, retroperitoneal lymph node dissection was performed, but failed to show any residual viable cells. An ultrasonic study did not reveal any testicular tumors. About 4 years after the previous treatment, he presented with scrotal enlargement and tumor markers such as AFP and HCG β were within normal limit. A right orchiectomy was performed on 23rd July. Pathology showed the resected tumor was a seminoma with CIS (Figure 3A,3B). No recurrence has been seen since the surgery (Figure 1B).

Photomicrograph of classic seminoma of the testis. A: H&E section shows compact nests of large tumor cells are separated by thin fibrous septa infiltrated by lymphocytes. B: Intratubular germ cell neoplasia in H&E section (×100). A row of atypical germ cells with clear cytoplasm is seen against a thickened basement membrane. No spermatogenesis is occurring in this tubule (×200).

Conclusions

There are reports that approximately 4% of patients with EGGCT develop a metachronous testicular cancer despite the use of cisplatin-based chemotherapy [7], and the cumulative risk of developing a metachronous testicular cancer 10 years after a diagnosis of EGGCT is 10.3% [8]. However, there is disagreement over whether EGGCT is a primary disease or metastatic from the burned-out primary testicular lesion. Actually, burned-out tumors have been detected in 76% of cases of EGGCT [9]. CIS is also found via biopsy in 31–42% cases [4, 10]. Testicular CIS is thought to have resistance to systemic chemotherapies and to develop later to metachronous testicular cancer. In the present case, the EGGCT was a non-seminomatous germ cell tumor including a yolk sac component, whereas the testicular cancer was a seminoma. We believe CIS was present at the time of the treatment of EGGCT and testicular CIS is so primitive that it could differentiate into any type of germ cells. It is also possible that these metachronously developing germ cell tumors developed independently. A testicular biopsy could clarify the relationship between these tumor cells and the expansion of the disease. In the present case no biopsy was done, but an ultrasonic examination ruled out the possibility of testicular CIS. Giwercman et al. [11] emphasized the necessity of histological examinations of the testis upon an evaluation of EGGCT [12–14] and also urged a careful follow-up for patients with EGGCT who do not have simultaneous testicular cancer.

On the other hand, there is an opinion that any patients with retroperitoneal masses should undergo scrotal ultrasound. Comiter et al. [15] showed definite pathological evidence of a burned-out testicular carcinoma in 5 of 6 patients (83%) with presumed extragonadal germ cell tumors and concluded that scrotal ultrasound studies are useful for the evaluation of the palpably normal testes [15]. Kitahara et al. reviewed the incidence of scrotal echogenic leisions with testicular cancers or burned-out tumors of 22 EGGCT patients and found echogenic changes in 17 patients (77.3%) [16]. This means that disease was overlooked by ultrasonic examinations in 22.7% of cases.

In our case, it is possibile that metachronous testicular cancer oriented in testicular CIS, grew from a burned-out tumor, or was independent of the EGGCT. We should have performed testicular biopsies at the time of the diagnosis of EGGCT and reflect the strategies of treatments of EGGCT.

Now we propose a surveillance protocol of EGGCT as Table 1, concerning with following four points.

-

1.

As we mentioned, the overall risk of development a testicular tumor is not so high(4–10.3%).

-

2.

The side effect of CIS therapy (whether irradaition, orchiectomy or chemotherapy) are significant, especially concerning fertility and androgen production.

-

3.

Testicular tumors early detected by adequate surveillance respond well to treatments.

-

4.

Testicular biopsy is not entitled to detect all the CIS.

References

Dueland S, Stenwig AE, Heilo A, Hoie J, Ous S, Fossa SD: Treatment and outcome of patients with extragonadal germ cell tumours – the Norwegian Radium Hospital's experience 1979–94. Br J Cancer. 1998, 77: 329-35.

Chaganti RS, Rodriguez E, Mathew S: Origin of adult male mediastinal germ-cell tumours. Lancet. 1994, 343: 1130-2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(94)90235-6.

de Bruin TW, Slater RM, Defferrari R, Geurts van Kessel A, Suijkerbuijk RF, Jansen G, de Jong B, Oosterhuis JW: Isochromosome 12p-positive pineal germ cell tumor. Cancer Res. 1994, 54: 1542-4.

Daugaard G, Rorth M, Cvon der Maase H, et al: Management of extragonadal germ-cell tumors and the significance of bilateral testicular biopsies. Ann Oncol. 1992, 3: 283-289.

Reinberg Y, Manivel JC, Fraley EE: Carcinoma in situ of the testis. J Urol. 1989, 142: 243-247.

Skakkebaek NE: Carcionam in situ of the testis: frequency and relationship to invasive germ cell tumors in infertile men. Histopathology. 1978, 2: 157-

Harland SJ, Cook PA, Fossa SD, et al: Risk factors for carcinoma in situ of the contralateral testis in patients with testicular cancer. Eur Urol. 1993, 23: 115-118. An interim report

Bokemeyer C, Hartmann JT, Fossa SD, Droz JP, Schmol HJ, Horwich A, Gerl A, Beyer J, Pont J, Kanz L, Nichols CR, Einhorn L: Extragonadal germ cell tumors: relation to testicular neoplasia and management options. APMIS. 2003, 111: 49-59. 10.1034/j.1600-0463.2003.11101081.x. discussion 59-63

Scholz M, Zehender M, Thalmann GN, Borner M, Thoni H, Studer UE: Extragonadal retroperitoneal germ cell tumor: evidence of origin in the testis. Ann Oncol. 2002, 13: 121-4. 10.1093/annonc/mdf003.

Fossa SD, Aass N, Heilo A, Daugaard G, Skakkebaek NE, Stenwig AE, Nesland JM, Looijenga LH, Oosterhuis JW: Testicular carcinoma in situ in patients with extragonadal germ-cell tumours: the clinical role of pretreatment biopsy. Ann Oncol. 2003, 14: 1412-8. 10.1093/annonc/mdg373.

Giwercman A, von der M aase H, Skakkebaek NE: Epidemiological and clinical aspects of carcinoma in situ of the testis. Eur Urol. 1993, 23: 104-10. discussion 111-4

Mumperow G, Lauke H, Holstein AF, et al: Further practical experiences in the recognition and the management of carcinoma in situ of the testis. Urol Int. 1992, 48: 162-166.

Gleich P: Testicular carcinoma in situ and nonpalpable seminoma eight years after contralateral teratocarcinoma. Urology. 1990, 36: 181-182.

Kimura F, Watanabe S, Shimizu S, Nakajima F, Hayakawa M, Nakamura H: Primary seminoma of the prostate and embryonal cell carcinoma of the left testis in one patient: a case report. Jpn J Urol. 1995, 86: 1497-1500.

Comiter CV, Benson CJ, Capelouto CC, Kantoff P, Shulman L, Richie JP, Loughlin KR: Nonpalpable intratesticular masses detected sonographically. J Urol. 1995, 154: 1367-9. 10.1097/00005392-199510000-00029.

Kitahara K, Hori J, Tokumitsu M, Saga Y, Hashimoto H, Kaneko S, Yachiku S: Retroperitoneal germ cell tumor with testicular calcification indicating tiny testicular origin: consideration of the origin of retroperitoneal germ cell tumors: report of two cases Hinyokika Kiyo. Review Japanese. 2003, 49: 291-5.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2490/4/13/prepub

Acknowledgements

We thank the patient for giving consent for publication of this case report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contribution

IK, MU, HY, KN, TT and ND carried out clinical treatments.

TM carried out histopathological studies.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Kuroda, I., Ueno, M., Mitsuhashi, T. et al. Testicular seminoma after the complete remission of extragonadal yolk sac tumor : a case report. BMC Urol 4, 13 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2490-4-13

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2490-4-13