Abstract

Background

Late prognosis of Community-Acquired Pneumonia (CAP) patients is related to cardiovascular events. Persistence of inflammation-related markers, defined by high circulatory levels of interleukin 6 and 10 (IL-6/IL-10), is associated with a higher post-event mortality rate for CAP patients. However, association between these markers and other components of the immune response, and the risk of cardiovascular events, has not been adequately explored. The main objectives of this study are: 1) to quantify the incidence of cardiovascular disease, in the year post-dating their hospital admittance due to CAP and, 2) to describe the distribution patterns of a wide spectrum of inflammatory markers upon admittance to and release from hospital, and to determine their relationship with the incidence of cardiovascular disease.

Methods/design

A cohort prospective study. All patients diagnosed and hospitalized with CAP will be candidates for inclusion. The study will take place in the Universitary Hospital La Princesa, Spain, during two years. Two samples of blood will be taken from each patient: the first upon admittance and the second one prior to release, in order to analyse various immune agents. The main determinants are: pro-adrenomedullin, copeptin, IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-17, IFN-γ, IL-10 and TGF-β, E-Selectin, ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and subpopulations of peripheral T lymphocytes (T regulator, Th1 and Th17), together with other clinical and analytical variables. Follow up will start at admittance and finish a year after discharge, registering incidence of death and cardiovascular events. The main objective is to establish the predictive power of different inflammatory markers in the prognosis of CAP, in the short and long term, and their relationship with cardiovascular disease.

Discussion

The level of some inflammatory markers (IL-6/IL-10) has been proposed as a means to differentiate the degree of severity of CAP, but their association with cardiovascular risk is not well established. In this study we aim to define new inflammatory markers associated with cardiovascular disease that could be helpful for the prognosis of CAP patients, by describing the distribution of a wide spectrum of inflammatory mediators and analyzing their association with the incidence of cardiovascular disease and mortality one year after release from hospital.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Community acquired pneumonia (CAP) is an important worldwide health problem. It is the most frequent infectious disease requiring hospitalization. The Incidence of CAP in Europe ranges from 1.2 to 11.6 cases per 1000 of population per year, with rates of hospitalization ranging from 40 to 60% [1, 2].

The mortality rate of CAP during hospitalization is well known. But various authors have reported an increased mortality rate after a long-term follow-up of hospitalized, Community-Acquired Pneumonia (CAP) patients who survived the illness. It has even been observed after allowing for age and co-morbidity. This tendency has been related to the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) risk scale [3–9].

It is known that significant cardiac complications are produced in a large proportion of CAP patients [10–13], with a greater incidence at the outset of the event, but also during its evolution and follow-up. Perry et al. [14], in connection with a very broad sample (50,119 subjects), recently published that a significant number of patients, with follow-up during 90 days after admittance for CAP, experienced a cardiovascular event, principally during hospitalization, with a rate of 1.5% for myocardial infarction, 10.2% for congestive heart failure, 9.5% for arrhythmia, 0.8% for unstable angina and 0.2% for ictus. Other authors previously had already described this relationship [15, 16].

Likewise Jasti et al. [17] described how the majority of readmissions after CAP resulted from cardio-pulmonary or underlying neurological diseases. Corrales-Medina et al. [18] also described the association between acute bacterial pneumonia and acute coronary syndrome. Besides, the relationship between coagulation disorders and CAP has also been reported [19].

Epidemiological data have shown a strong relationship between acute respiratory infections and a later myocardial infarction [20, 21]. Furthermore, it is known that chronic inflammation destabilizes atheroma plaque and induces a pro-coagulant state [22]. Very recently it has been described that an important number of patients have new cardiac arrhythmia during and post-hospitalization for pneumonia [23].

Altogether these observations suggest that the way of regarding CAP should be changed: early diagnosis, better monitoring, and risk stratification in CAP with respect to cardiovascular diseases should be established.

A growing interest has developed in identifying different biological markers suitable for establishing a correct diagnosis and adequately evaluating the severity and prognosis of the disease [24–27]. Various candidate biomarkers have been studied, including inflammatory molecules such as C-reactive protein, IL-6, IL-1 and procalcitonin and also cardiovascular biomarkers such as proatrial natriuretic peptide (pro-ANP), proarginin-vasopresin (copeptin), proendothelin-1 and Mid-regional pro-adrenomedullin (MR-Pro-ADM). These cardiovascular biomarkers are good predictors, both in the short and in the long term, for the prognosis of CAP [26]. In a reference study, MR-pro-ADM resulted to be the most useful biomarker [25]. Moreover, it also was an excellent marker to predict short and long term mortality in CAP, regardless of its etiology [28].

It has been reported that persistent high circulatory levels of IL-6 and IL-10 after CAP are associated with an increased mortality in the follow-up [29, 30], pointing to a relationship between a persistent inflammation upon release from hospital and the long-term prognosis. Moreover, in apparently healthy subjects, high levels of IL-6 are related with a greater risk of myocardial infarction in the future [31]. It remains to be established whether these inflammatory mediators could be used as biomarkers for prognosis of cardiovascular risk in CAP patients.

Immune response is very complex and many other molecules might be used as biomarkers. Of great relevance in the long-term inflammatory response against infectious agents is the generation of the T lymphocyte effectors type Th1 and Th17, which are capable of mediating the inflammatory response by means of their cytokine effectors IFN-γ and IL-17 in response to such infectious agents [32, 33]. Likewise, the unregulated action of these cellular populations is involved in numerous autoimmune inflammatory processes [34, 35]. The inflammatory state is negatively regulated by factors such as anti-inflammatory cytokines like IL-10 (already studied in CAP) and TGF-β [36] and by T regulator lymphocytes (Treg). The Treg cell populations, characterized by the expression of certain markers such as the transcription factor FoxP3, are capable of attenuating the inflammatory response mediated by T cells in numerous pathological processes [37]. The balance between all these pro and anti-inflammatory factors determines the inflammatory state of the organism. During inflammatory processes the activation of the vascular endothelium increases the expression of inducible leukocyte adhesion molecules such as ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-selectin which mediate the adhesion and extravasation of leukocytes to the inflammation site [38]. During the inflammatory process which affects the endothelial barrier, an increase in the soluble forms of these molecules liberated to the extracellular medium is produced in such a way that their circulatory levels may be indicators of inflammatory processes related with cardiovascular risk [39]. All these mediators of immune response could be considered as candidate biomarkers to evaluate cardiovascular risk and prognosis in CAP.

The current research project intends to quantify the incidence and mortality of cardiovascular disease in adult patients, in the year after hospital admission due to CAP.

Moreover, this project tries to describe a wide spectrum of immune response mediators upon admission to and release from hospital in CAP patients. Many of these mediators have been already studied in CAP but some others will be analyzed for the first time.

Our aim is to establish a profile of the inflammatory state of these patients and determine its possible relationship with the incidence of cardiovascular disease.

Methods/design

A cohort prospective study to determine the prognosis and the incidence of cardiovascular events after admission to hospital due to a CAP episode and the predictive value of a wide panel of biological inflammatory markers. All the patients will be followed up on for at least one year after discharge and every new cardiovascular event will be recorded. The study will take place in the University Hospital “La Princesa” (HUP), a reference center for emergencies and admissions for three hundred thousand inhabitants in the Northeastern area of Madrid (Spain).

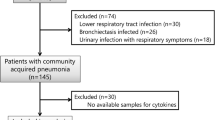

Candidates for this study will be all those patients who are attended to and are subsequently admitted to the hospital due to CAP between 01/01/2014 and 31/12/2015. They must satisfy the following conditions: be older than 18, show symptoms of lower airway infection, together with the existence of fresh radiological infiltrate, and be then diagnosed with pneumonia and subsequently admitted. There must be no alternative diagnoses during follow-up, and the subjects must not have been hospitalized in at least the ten days preceding the current episode. Signed informed consent will be required. The exclusion criteria will concern those patients who are unreachable during the follow-up time.

The Clinical Research Ethics Coimmittee of the hospital has approved this study.

Main outcomes or primary outcome

The dependent variable in this study is the development of cardiovascular disease according to the following clinical criteria: pacemaker emplacement, acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, acute pulmonary edema, unstable angina, ictus, transitory ischemic cerebral affectation, pulmonary thrombo-embolism and deep venous thrombosis. Moreover, mortality from cardiovascular diseases or any other cause will be registered. These events will be collated during the episode of CAP and during follow-up over one year. Furthermore, the follow-up point at which a cardiovascular event diagnosis or death occurs will be collated with the aim of estimating the incidence in terms of incident density.

Independent variables

Upon admittance to the emergency department: age, gender, previous antibiotic treatment (type, days, and dosage), vaccination condition (flu and pneumococcal) will be registered as independent variables. In addition, current treatment, especially in relation with cardiovascular disease - antiaggregants, oral anticoagulants, beta-blockers, calcium-antagonists, ACE inhibitors, Angiotensin II receptor blockers, Direct renin inhibitor, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, anti-arrhythmics, insulin, oral hypoglucemiants, fibrates, niacin, omega three, fit sterols – will also be recorded.

Co-morbidities

Smoking status (packs per year), alcohol consumption, Charlson index [40], peripheral arterial disease (symptomatic or asymptomatic), previous stroke (established or transient ischemic attack), diabetes, obesity, high blood pressure, dyslipemia, chronic kidney disease (glomerular filtration rate –GFR- < 60 ml/m and/or increased high fractional excretion of albumin), liver disease, HIV infection, neoplasic disease, collagen disease, ischemic cardiopathy (MI or revascularization), previous pulmonary thromboembolism or deep venous thrombosis, ICU admission, prior pneumonia and cardiovascular risk evaluation in accordance with the score [41] will all be taken into consideration.

During hospitalization

CURB-65 [42], PSI [43], sepsis, septic shock, pleural effusion, empyema, multilobar impairment, hospital stay, admittance to ICU, need for assisted ventilation, microbiological results.

Analytical parameters

Peripheral blood samples will be taken on admittance and near to discharge. The time of the second sample corresponding to release has been standardized to being between the third and the fifth day after the admittance of the patient in order to avoid sample acquisition losses for the project (see Figure 1). This decision was taken based on the effects of the treatment administered to the patient and its repercussions on the inflammatory markers.

In both samples the following will be determinated: cholesterol levels (LDL, HDL), triglycerides, glucose, HbA1c, creatinine, urea, GFR, ions, blood cell counts, c reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation, fibrinogen and coagulation. Besides these, several biological markers will be analyzed (see below).

Biological markers

One part of the blood sample will be processed to obtain serum which will be frozen at - 80°C in order to study soluble mediator levels. Another part of the blood sample will be used to analyze, by flow cytometry, the sub-populations of the T, Th1, Th17 and T regulator lymphocytes.

-

1.

Soluble Mediator Study: pro-adrenomedullin and copeptin. pro-inflammatory cytokines: IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-17, IFN-γ. Anti-inflammatory cytokines: IL-10 and TGF-β. Soluble endothelial adhesion molecules: E-Selectin, ICAM-1 and VCAM-1.

Determination of the levels of these soluble molecules will be carried out using the commercially available kit BD CBA Cytometric Bead Array (CBA) Human Soluble Protein Flex Set. This allows the simultaneous quantification, by flow cytometry, of multiple proteins at a very low concentration (10–2500 pg/mL) in serum samples. Flow cytometry will be carried out with a FACs (Fluorescence-activated cell sorting) CANTO cytometer and FCAP Array™ Software will be used for the analysis and quantifications. Due to the technical limitations of the trial, the quantification of soluble serum factors will be carried out in batches of 90 stored serum samples.

-

2.

Sub-populations of T Lymphocytes: by using flow cytometry on peripheral blood lymphocytes to detect CD4, the intracellular transcription factor FoxP3, intracellular cytokine IFN-γ and intracellular cytokine IL-17 will be determined. The proportion of T regulatory lymphocytes will be defined as the percentage of lymphocytes CD4 + FoxP3+. The proportion of type Th1 T-lymphocytes in peripheral blood will be determined by the proportion of lymphocytes CD4+ IFN-γ+. The proportion of Th17 T-lymphocytes will be defined by the proportion of lymphocytes CD4 + IL-17 + .

For the intracellular biomarkers IL-17 and FoxP3 the use of a human Th17/Treg phenotyping kit (BD Human Th17-Treg Phenotyping Kit) has been chosen with the addition of an Anti-Human IFN-γ. Before marking, stimulation of PBMC (Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell) by means of PMA (Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate), Ionomycin and GolgiStop™, fixation and permeabilization with specific buffers for FoxP3 and marking using a cocktail of FoxP3, IL-17, IFN-γ and CD4 antibodies will be performed. Its interpretation will be carried out through a FACs CALIBUR cytometer and its analysis by means of the CellQuest Pro program.

Follow-up after discharge

There will be at least three visits during follow-up: at one month, at three months and at one year (see Figure 1). If the patient does not attend, a follow-up will be carried out by telephone to determine the cause of absence and a questionnaire will be completed after consultation with the relevant primary care doctor. If the patient is admitted to the center, suffers a cardiovascular event or dies, the pertinent information will be recorded according to primary outcome.

Data collection method

An electronic, data-collection log, integrated into the hospital’s clinical background system, has been specifically developed for the purposes of this study. The demographic and attendance record information in the study’s data base will be obtained from the general information system to avoid duplication. Access to the data collection log will be restricted, by means of user ID and password, to the study’s researchers, and with its back-up copy policy being the same as that for the general system.

Statistical analysis

Sample size

Assuming a cumulative cardiovascular event incidence rate of 20% for the first year after hospital release, in order to carry out such an estimate with a confidence interval (CI) of 95% and with an accuracy of 5%, 243 patients would be necessary. Nevertheless, since antecedents for other similar studies could not be found, and, taking into account that relationships with molecules not previously studied are going to be tested, it has been decided that a sample as large as the recruitment time period permits (2 years) will be used, thus also allowing the possible seasonal effect to be controlled. An approximate average of 600 patients per year are attended to in the Emergency Department with a CAP diagnosis, of which 400 per year are admitted to the hospital, according to the records of the centre. Under these circumstances, and allowing for exclusions, it is estimated that it will be possible to comply with the stated objectives within the set timescale. Furthermore, in order to avoid unnecessary work, 2 intermediate sequential analyses will be carried out when at least 50% of the estimated sample have completed their first year of follow-up so that the estimated value for each molecule may be known before the end of the study. An annual cut-off point will be established for the evaluation of results, potential adverse effects and possible publications.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis will be carried out by quantitative variables which will be described by their measures of central tendency (mean) and dispersion (standard deviation); qualitative variables will be described by their proportion and standard error. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression will be used to analyze the association between the independent variables and cumulative incidence. Also odds ratios, standard errors and the corresponding test hypothesis will be estimated. The analysis of the association between the qualitative variables will be carried out using the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test and comparing the means of different quantitative variables between subgroups will be performed using t-test or ANOVA, or their nonparametric equivalent (Mann-Whiney or Kruskal-Wallis).

The dependent variables will also be analyzed with respect to time: firstly by estimating their incidence density and risk functions according to the Kaplan-Meier method with an appropriate hypothesis test (log-rank, Breslow, Tarone or others), and secondly by using Cox regression models after checking proportionality risk hypotheses. In all cases model construction will be done according to the principle of parsimony in order to include a limited number of variables. All values of p < 0.05 will be considered to be statistically significant. In selection processes p <0.10 or p < 0.15 will be used as a threshold value. Statistical analysis will be carried out using the program Stata v12.0 in the Methodology Unit of the Princesa Research Institute.

Discussion

The importance of CAP as a serious health problem, its high cost in terms of morbidity and mortality and its special relationship with the elderly, are widely-recognized clinical facts. Patients hospitalized with a CAP diagnosis display, after admittance, a higher mortality than patients of their same age and degree of co-morbidity, and also show a higher incidence of cardiovascular disease, both in the long and the short term. Thus, new CAP prognosis scores, which take the appearance of cardiovascular events into account, have been proposed [44, 45]. Various studies dealing with the handling of CAP with the help of several biomarkers have also been published [46–48]. Likewise, articles that try to differentiate between the degree of severity of CAP (severe or non-severe) according to the measurable activity of inflammatory markers [49–51], or help to improve patient stratification in accordance with their levels of inflammatory cytokines, have been published [29]. The inflammatory response to infection produced in patients with CAP could be the cause of cardiovascular complications modifying the prognosis of the disease [10]. Therefore, studying inflammation markers could help to monitor cardiovascular risk and prognosis in CAP patients.

Pneumonia is an exuberant sequestration of peripheral neutrophils in the lungs, which is tightly regulated by cascades of cytokines produced by the immune system in response to an invading pathogen [52, 53]. In an ideal scenario, the acute lung inflammation is protective and self-limiting, and once the infection has been controlled, cytokines also function in restoring homeostasis, including the modulation of neutrophil apoptosis. On the other hand, a cytokine storm results in a deleterious inflammation and poor clinical outcome [53]. The contribution of cytokines to systemic inflammatory response, together with plaque instability, sympathetic activation, a pro-coagulatory state and endothelial dysfunction, could lead to myocardial damage, arrhythmia and heart failure [10].

In the current research project we aim to study the distribution, in these patients, of a wide spectrum of immune response mediators upon admittance to and release from hospital and establish their possible relationship with the incidence of cardiovascular disease, and mortality. This will permit the establishment of a profile of the inflammatory state of these patients and determine its association with cardiovascular risk.

Although the exact role of each immune mediator in the inflammatory response during pneumonia is still a subject of ongoing research, it is clear that different inflammatory patterns are elicited by microorganisms [54].

In the present study we plan to analyze a panel of immune/inflammatory mediators that include: pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-17, IFN-γ), anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10 and TGF-β); soluble endothelial adhesion molecules (E-Selectin, ICAM-1 and VCAM-1) and Th1, Th17 and Treg lymphocytes. Although they are grouped in this way, the classification of cytokines as pro- and anti-inflammatory is not absolute, since many cytokines are capable of exerting both effects depending on a variety of factors [53, 55, 56], and some patterns of cytokine response could best be described based on their concentrations as high, medium and low, rather than their pro-or anti-inflammatory activities [57]. In addition to cytokines, we will study parameters of immune response such as soluble endothelial adhesion molecules, Th1 and Th17 effector lymphocytes and T regulatory lymphocytes not tested previously in CAP. This set of mediators covers a wide range of processes regulating immune response and inflammation. Their analysis will help to characterize an accurate inflammatory profile of CAP patients and identify candidate inflammatory markers of cardiovascular risk in CAP.

The time during follow-up at which samples for the determination of inflammatory mediators should be taken is an important point for this work. At which time point would determinations better predict cardiovascular risk and evolution/outcome? The average lifespan of the markers needs to be considered. Many cytokines involved in this process have a short half-life and they could be reduced shortly after the induction of the inflammatory response to almost undetectable levels. Accordingly, mean cytokine concentrations are generally highest on admission and they decline rapidly over the first few days. Therefore, measurements of blood samples taken at the time of admission might allow us to better assess the risk for a CAP episode. However, whereas a persistent, up-regulated, pro-inflammatory response is associated with deaths due to cardiovascular disease, renal failure, infection, and cancer, persistent low-grade inflammation and immune suppression may play an important role in coronary events, cerebral-vascular events, and repeat bouts of CAP [31, 53, 58–61]. Therefore, when measured at the end of hospitalization, rather than on admission cytokine levels might actually be more predictive of adverse outcomes after hospitalization. In the current study, blood samples for the determination of inflammatory markers will be taken at both time points. In this way we will be able to establish the best time point for each marker.

In this study we aim at describing the distribution of a wide spectrum of inflammatory markers upon the admittance to and release from hospital of CAP patients, and analyze their association with the incidence of cardiovascular disease and mortality one year after release from hospital. In this way new inflammatory markers associated with cardiovascular disease in these patients may be defined. These new markers could be helpful for prognosis. The development of predictive models provides crucial evidence for the transference of laboratory findings to human beings and from clinical research to clinical practice. The possibility of precisely personalizing healthcare interventions seems to be related with the amount of combined factors in forecasting models [62].

Abbreviations

- CAP:

-

Community-acquired pneumonia

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- GFR:

-

Glomerular filtration rate

- ICAM:

-

Intercellular adhesion molecule

- IFN:

-

Interferon

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- MR-Pro-ADM:

-

Mid-regional pro-adrenomedullin

- PSI:

-

Pneumonia severity index

- TNF:

-

Tumor necrosis factor

- TFG:

-

Transforming growth factor

- VCAM:

-

Vascular cell adhesion molecule.

References

World Health Organization: The top 10 causes of death. 2013, Geneva: World Health Organization, Available from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs310/en/index.html

Welte T, Torres A, Nathwani D: Clinical and economic burden of community-acquired pneumonia among adults in Europe. Thorax. 2012, 67: 71-79. 10.1136/thx.2009.129502.

Wunderink RG, Waterer GW: Clinical practice. Community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2014, 370 (6): 543-551. 10.1056/NEJMcp1214869.

Brancati FL, Chow JW, Wagener MM, Vacarello SJ, Yu VL: Is pneumonia really the old man's friend? Two-year prognosis after community-acquired pneumonia. Lancet. 1993, 342 (8862): 30-33. 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91887-R.

Waterer GW, Kessler LA, Wunderink RG: Medium-term survival after hospitalization with community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004, 169 (8): 910-914. 10.1164/rccm.200310-1448OC.

Yende S, Angus DC, Ali IS, Somes G, Newman AB, Bauer D, Garcia M, Harris TB, Kritchevsky SB: Influence of comorbid conditions on long-term mortality after pneumonia in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007, 55 (4): 518-525. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01100.x.

Bordon J, Wiemken T, Peyrani P, Paz ML, Gnoni M, Cabral P, Venero Mdel C, Ramirez J: Decrease in long-term survival for hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2010, 138 (2): 279-283. 10.1378/chest.09-2702.

Johnstone J, Eurich DT, Majumdar SR, Jin Y, Marrie TJ: Long-term morbidity and mortality after hospitalization with community-acquired pneumonia: a population-based cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2008, 87 (6): 329-334. 10.1097/MD.0b013e318190f444.

Adamuz J, Viasus D, Jimenez-Martinez E, Isla P, Garcia-Vidal C, Dorca J, Carratalà J: Incidence, timing and risk factors associated with 1-year mortality after hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia. J Infect. 2014, 68: 534-541. 10.1016/j.jinf.2014.02.006.

Kruger S, Frechen D: Cardiovascular complications and comorbidities in CAP. European Respiratory monograph. Edited by: Chalmers JD, Pletz MW, Aliberti S. 2014, Sheffield: Europen Respiratory Society, 256-265.

Corrales-Medina VF, Suh KN, Rose G, Chirinos JA, Doucette S, Cameron DW, Fergusson DA: Cardiac complications in patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS Med. 2011, 8 (6): e1001048-10.1371/journal.pmed.1001048.

Corrales-Medina VF, Musher DM, Wells GA, Chirinos JA, Chen L, Fine MJ: Cardiac complications in patients with community-acquired pneumonia: incidence, timing, risk factors, and association with short-term mortality. Circulation. 2012, 125 (6): 773-781. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.040766.

Peyrani P, Ramirez J: What is the association of cardiovascular events with clinical failure in patients with community-acquired pneumonia?. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2013, 27 (1): 205-210. 10.1016/j.idc.2012.11.010.

Perry TW, Pugh MJ, Waterer GW, Nakashima B, Orihuela CJ, Copeland LA, Restrepo MI, Anzueto A, Mortensen EM: Incidence of cardiovascular events after hospital admission for pneumonia. Am J Med. 2011, 124 (3): 244-251. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.11.014.

Musher DM, Rueda AM, Kaka AS, Mapara SM: The association between pneumococcal pneumonia and acute cardiac events. Clin Infect Dis. 2007, 45 (2): 158-165. 10.1086/518849.

Ramirez J, Aliberti S, Mirsaeidi M, Peyrani P, Filardo G, Amir A, Moffett B, Gordon J, Blasi F, Bordon J: Acute myocardial infarction in hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2008, 47 (2): 182-187. 10.1086/589246.

Jasti H, Mortensen EM, Obrosky DS, Kapoor WN, Fine MJ: Causes and risk factors for rehospitalization of patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2008, 46 (4): 550-556. 10.1086/526526.

Corrales-Medina VF, Serpa J, Rueda AM, Giordano TP, Bozkurt B, Madjid M, Tweardy D, Musher DM: Acute bacterial pneumonia is associated with the occurrence of acute coronary syndromes. Medicine (Baltimore). 2009, 88 (3): 154-159. 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181a692f0.

Milbrandt EB, Reade MC, Lee M, Shook SL, Angus DC, Kong L, Carter M, Yealy DM, Kellum JA: Prevalence and significance of coagulation abnormalities in community-acquired pneumonia. Mol Med. 2009, 15 (11–12): 438-445.

Madjid M, Miller CC, Zarubaev VV, Marinich IG, Kiselev OI, Lobzin YV, Filippov AE, Casscells 3rd SW: Influenza epidemics and acute respiratory disease activity are associated with a surge in autopsy-confirmed coronary heart disease death: results from 8 years of autopsies in 34,892 subjects. Eur Heart J. 2007, 28 (10): 1205-1210. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm035.

Smeeth L, Thomas SL, Hall AJ, Hubbard R, Farrington P, Vallance P: Risk of myocardial infarction and stroke after acute infection or vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2004, 351 (25): 2611-2618. 10.1056/NEJMoa041747.

Stoll G, Bendszus M: Inflammation and atherosclerosis: novel insights into plaque formation and destabilization. Stroke. 2006, 37 (7): 1923-1932. 10.1161/01.STR.0000226901.34927.10.

Soto-Gomez N, Anzueto A, Waterer GW, Restrepo MI, Mortensen EM: Pneumonia: an arrhythmogenic disease?. Am J Med. 2013, 126 (1): 43-48. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.08.005.

Christ-Crain M, Morgenthaler NG, Stolz D, Muller C, Bingisser R, Harbarth S, Tamm M, Struck J, Bergmann A, Müller B: Pro-adrenomedullin to predict severity and outcome in community-acquired pneumonia[ISRCTN04176397]. Crit Care. 2006, 10 (3): R96-10.1186/cc4955.

Kruger S, Ewig S, Giersdorf S, Hartmann O, Suttorp N, Welte T: Cardiovascular and inflammatory biomarkers to predict short- and long-term survival in community-acquired pneumonia: Results from the German Competence Network, CAPNETZ. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010, 182 (11): 1426-1434. 10.1164/rccm.201003-0415OC.

Kruger S, Welte T: Biomarkers in community-acquired pneumonia. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2012, 6 (2): 203-214. 10.1586/ers.12.6.

Schuetz P, Litke A, Albrich WC, Mueller B: Blood biomarkers for personalized treatment and patient management decisions in community-acquired pneumonia. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2013, 26 (2): 159-167.

Bello S, Lasierra AB, Minchole E, Fandos S, Ruiz MA, Vera E, de Pablo F, Ferrer M, Menendez R, Torres A: Prognostic power of proadrenomedullin in community-acquired peumonia is independent on etiology. Eur Respir J. 2012, 39 (5): 1144-1155. 10.1183/09031936.00080411.

Martinez R, Menendez R, Reyes S, Polverino E, Cilloniz C, Martinez A, Esquinas C, Filella X, Ramírez P, Torres A: Factors associated with inflammatory cytokine patterns in community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2011, 37 (2): 393-399. 10.1183/09031936.00040710.

Yende S, D'Angelo G, Kellum JA, Weissfeld L, Fine J, Welch RD, Kong L, Carter M, Angus DC: Inflammatory markers at hospital discharge predict subsequent mortality after pneumonia and sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008, 177 (11): 1242-1247. 10.1164/rccm.200712-1777OC.

Ridker PM, Rifai N, Stampfer MJ, Hennekens CH: Plasma concentration of interleukin-6 and the risk of future myocardial infarction among apparently healthy men. Circulation. 2000, 101 (15): 1767-1772. 10.1161/01.CIR.101.15.1767.

Paats MS, Bergen IM, Hanselaar WE, van Zoelen EC, Verbrugh HA, Hoogsteden HC, van den Blink B, Hendriks RW, van der Eerden MM: T helper 17 cells are involved in the local and systemic inflammatory response in community-acquired pneumonia. Thorax. 2014, 68 (5): 468-474.

Kudva A, Scheller EV, Robinson KM, Crowe CR, Choi SM, Slight SR, Khader SA, Dubin PJ, Enelow RI, Kolls JK, Alcorn JF: Influenza A inhibits Th17-mediated host defense against bacterial pneumonia in mice. J Immunol. 2011, 186 (3): 1666-1674. 10.4049/jimmunol.1002194.

Kolls JK, Khader SA: The role of Th17 cytokines in primary mucosal immunity. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010, 21 (6): 443-448. 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2010.11.002.

Korn T, Oukka M, Kuchroo V, Bettelli E: Th17 cells: effector T cells with inflammatory properties. Semin Immunol. 2007, 19 (6): 362-371. 10.1016/j.smim.2007.10.007.

Li MO, Wan YY, Sanjabi S, Robertson AK, Flavell RA: Transforming growth factor-beta regulation of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006, 24: 99-146. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090737.

Shevach EM: Biological functions of regulatory T cells. Adv Immunol. 2011, 112: 137-176.

Ley K, Laudanna C, Cybulsky MI, Nourshargh S: Getting to the site of inflammation: the leukocyte adhesion cascade updated. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007, 7 (9): 678-689. 10.1038/nri2156.

Demerath E, Towne B, Blangero J, Siervogel RM: The relationship of soluble ICAM-1, VCAM-1, P-selectin and E-selectin to cardiovascular disease risk factors in healthy men and women. Ann Hum Biol. 2001, 28 (6): 664-678. 10.1080/03014460110048530.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR: A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987, 40 (5): 373-383. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8.

De Backer G, Ambrosioni E, Borch-Johnsen K, Brotons C, Cifkova R, Dallongeville J, Ebrahim S, Faergeman O, Graham I, Mancia G, Cats VM, Orth-Gomér K, Perk J, Pyörälä K, Rodicio JL, Sans S, Sansoy V, Sechtem U, Silber S, Thomsen T, Wood D, European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines: European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice Third Joint Task Force of European and other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice. Eur J Cardio Prev Rev. 2003, 10 (Suppl 1): S1-S78.

Lim WS, van der Eerden MM, Laing R, Boersma WG, Karalus N, Town GI, Lewis SA, Macfarlane JT: Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: an international derivation and validation study. Thorax. 2003, 58 (5): 377-382. 10.1136/thorax.58.5.377.

Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, Hanusa BH, Weissfeld LA, Singer DE, Coley CM, Marrie TJ, Kapoor WN: A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1997, 336 (4): 243-250. 10.1056/NEJM199701233360402.

Corrales-Medina VF, Taljaard M, Fine MJ, Dwivedi G, Perry JJ, Musher DM, Chirinos JA: Risk stratification for cardiac complications in patients hospitalized for community-acquired pneumonia. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014, 89 (1): 60-68. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.09.015.

Viasus D, Garcia-Vidal C, Manresa F, Dorca J, Gudiol F, Carratala J: Risk stratification and prognosis of acute cardiac events in hospitalized adults with community-acquired pneumonia. J Infect. 2013, 66 (1): 27-33. 10.1016/j.jinf.2012.09.003.

Torres A, Ramirez P, Montull B, Menendez R: Biomarkers and community-acquired pneumonia: tailoring management with biological data. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2012, 33 (3): 266-271.

Kruger S, Welte T, Ewig S: Another view on the prediction of outcomes in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2011, 38 (4): 991-992. 10.1183/09031936.00039411. author reply 992–3

Ewig S, Torres A: Community-acquired pneumonia as an emergency: time for an aggressive intervention to lower mortality. Eur Respir J. 2011, 38 (2): 253-260. 10.1183/09031936.00199810.

Fernandez-Botran R, Uriarte SM, Arnold FW, Rodriguez-Hernandez L, Rane MJ, Peyrani P, Wiemken T, Kelley R, Uppatla S, Cavallazzi R, Blasi F, Morlacchi L, Aliberti S, Jonsson C, Ramirez JA, Bordon J: Contrasting Inflammatory Responses in Severe and Non-severe Community-acquired Pneumonia. Inflammation. 2014, 2014: 2014-

Paats MS, Bergen IM, Hanselaar WE, van Groeninx Zoelen EC, Hoogsteden HC, Hendriks RW, van der Eerden MM: Local and systemic cytokine profiles in nonsevere and severe community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2013, 41 (6): 1378-1385. 10.1183/09031936.00060112.

Ramirez P, Ferrer M, Marti V, Reyes S, Martinez R, Menendez R, Ewig S, Torres A: Inflammatory biomarkers and prediction for intensive care unit admission in severe community-acquired pneumonia. Crit Care Med. 2011, 39 (10): 2211-2217. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182257445.

Craig A, Mai J, Cai S, Jeyaseelan S: Neutrophil recruitment to the lungs during bacterial pneumonia. Infect Immun. 2009, 77 (2): 568-575. 10.1128/IAI.00832-08.

Bordon J, Aliberti S, Fernandez-Botran R, Uriarte SM, Rane MJ, Duvvuri P, Peyrani P, Morlacchi LC, Blasi F, Ramirez JA: Understanding the roles of cytokines and neutrophil activity and neutrophil apoptosis in the protective versus deleterious inflammatory response in pneumonia. Int J Infect Dis. 2013, 17 (2): e76-e83. 10.1016/j.ijid.2012.06.006.

Menendez R, Sahuquillo-Arce JM, Reyes S, Martinez R, Polverino E, Cilloniz C, Cilloniz C, Cordoba JG, Montull B, Torres A: Cytokine activation patterns and biomarkers are influenced by microorganisms in community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2012, 141 (6): 1537-1545. 10.1378/chest.11-1446.

Calbo E, Garau J: Of mice and men: innate immunity in pneumococcal pneumonia. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010, 35 (2): 107-113. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.10.002.

Kruger S, Ewig S, Kunde J, Hartmann O, Marre R, Suttorp N, Welte T: Assessment of inflammatory markers in patients with community-acquired pneumonia–influence of antimicrobial pre-treatment: results from the German competence network CAPNETZ. Clin Chim Acta. 2010, 411 (23–24): 1929-1934.

Kellum JA, Kong L, Fink MP, Weissfeld LA, Yealy DM, Pinsky MR, Fine J, Krichevsky A, Delude RL, Angus DC: Understanding the inflammatory cytokine response in pneumonia and sepsis: results of the Genetic and Inflammatory Markers of Sepsis (GenIMS) Study. Arch Intern Med. 2007, 167 (15): 1655-1663. 10.1001/archinte.167.15.1655.

Remick DG, Bolgos G, Copeland S, Siddiqui J: Role of interleukin-6 in mortality from and physiologic response to sepsis. Infect Immun. 2005, 73 (5): 2751-2757. 10.1128/IAI.73.5.2751-2757.2005.

Yende S, Tuomanen EI, Wunderink R, Kanaya A, Newman AB, Harris T, de Rekeneire N, Kritchevsky SB: Preinfection systemic inflammatory markers and risk of hospitalization due to pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005, 172 (11): 1440-1446. 10.1164/rccm.200506-888OC.

El Solh A, Pineda L, Bouquin P, Mankowski C: Determinants of short and long term functional recovery after hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly: role of inflammatory markers. BMC Geriatr. 2006, 6: 12-10.1186/1471-2318-6-12.

Mortensen EM, Coley CM, Singer DE, Marrie TJ, Obrosky DS, Kapoor WN, Fine MJ: Causes of death for patients with community-acquired pneumonia: results from the Pneumonia Patient Outcomes Research Team cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2002, 162 (9): 1059-1064. 10.1001/archinte.162.9.1059.

Riley RD, Hayden JA, Steyerberg EW, Moons KG, Abrams K, Kyzas PA, Malats N, Briggs A, Schroter S, Altman DG, Hemingway H: Prognosis Research Strategy (PROGRESS) 2: prognostic factor research. PLoS Med. 2013, 10 (2): e1001380-10.1371/journal.pmed.1001380.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2466/14/197/prepub

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by grants from Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (FIS) (PI 12/01142) and Spanish Respiratory Society (SEPAR 2013).

Funding

This work was supported by Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (FIS) (PI 12/01142) and Spanish Respiratory Society (SEPAR 2013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MO, SL, HF and AD will carry out the laboratory analyses and acquired of funding. JA, JG, JC, GF and BA drafted the manuscript and will collect data. OR, JA, CS and JA conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. LP and FR will perform the statistical analysis and helped to draft the manuscript. All of the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Rajas, O., Ortega-Gómez, M., Galván Román, J.M. et al. The incidence of cardiovascular events after hospitalization due to CAP and their association with different inflammatory markers. BMC Pulm Med 14, 197 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2466-14-197

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2466-14-197