Abstract

Background

The FUS-DDIT3 fusion oncogene encodes an abnormal transcription factor that has a causative role in the development of myxoid/round-cell liposarcomas (MLS/RCLS). We have previously identified FLT1 (VEGFR1) as a candidate downstream target gene of FUS-DDIT3. The aim of this study was to investigate expression of FLT1 and its ligands in MLS cells.

Methods

HT1080 human fibrosarcoma cells were transiently transfected with FUS-DDIT3-GFP variant constructs and FLT1 expression was measured by quantitative real-time PCR. In addition, FLT1, PGF, VEGFA and VEGFB expression was measured in MLS/RCLS cell lines, MLS/RCLS tumors and in normal adiopocytes. We analyzed nine cases of MLS/RCLS and one cell line xenografted in mice for FLT1 protein expression using immunohistochemistry. MLS/RCLS cell lines were also analyzed for FLT1 by immunofluorescence and western blot. MLS/RCLS cell lines were additionally treated with FLT1 tyrosine kinase inhibitors and assayed for alterations in proliferation rate.

Results

FLT1 expression was dramatically increased in transfected cells stably expressing FUS-DDIT3 and present at high levels in cell lines derived from MLS. The FLT1 protein showed a strong nuclear expression in cells of MLS tissue as well as in cultured MLS cells, which was confirmed by cellular fractionation. Tissue array analysis showed a nuclear expression of the FLT1 protein also in several other tumor and normal cell types including normal adipocytes. The FLT1 ligand coding gene PGF was highly expressed in cultured MLS cells compared to normal adipocytes while the other ligand genes VEGFA and VEGFB were expressed to lower levels. A more heterogeneous expression pattern of these genes were observed in tumor samples. No changes in proliferation rate of MLS cells were detected at concentrations for which the kinase inhibitors have shown specific inhibition of FLT1.

Conclusions

Our results imply that FLT1 is induced as an indirect downstream effect of FUS-DDIT3 expression in MLS. This could be a consequence of the ability of FUS-DDIT3 to hijack parts of normal adipose tissue development and reprogram primary cells to a liposarcoma-like phenotype. The findings of nuclear FLT1 protein and expression of corresponding ligands in MLS and normal tissues may have implications for tissue homeostasis and tumor development through auto- or intracrine signaling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Myxoid/round-cell liposarcoma (MLS/RCLS) is one of the most common forms of liposarcoma and accounts for about 40% of all cases [1]. The tumor cells are characterized by the FET family [2] FUS-DDIT3 fusion oncogene (also called TLS-CHOP) present in more than 90% of cases [3–5] or the EWS-DDIT3 found in a minority of cases [6]. The causative role of FUS-DDIT3 in the initiation of MLS/RCLS and its role for the MLS-specific tumor morphology have been demonstrated in transgenic mice, xenografts and with FUS-DDIT3 carrying mesenchymal stem cells [7–9].

FUS-DDIT3 encodes a protein consisting of the N-terminal half of the FUS protein juxtaposed to the DNA-binding basic leucine zipper transcription factor DDIT3 (also known as CHOP or GADD153) [4, 5]. The FUS-DDIT3 protein acts as an abnormal transcription factor [10] and the development of myxoid liposarcomas is thus regarded as a consequence of deregulated FUS-DDIT3 target genes [8, 9, 11]. In this study, we have investigated the expression of the putative FUS-DDIT3 target gene FLT1 and its encoded receptor tyrosine kinase in MLS cells.

Methods

Cell lines

The myxoid liposarcoma cell lines MLS 402-91, MLS 1765-92, MLS 2645-94 [3, 11] and human fibrosarcoma cell line HT1080 were kept frozen in liquid nitrogen or cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 in RPMI 1640 medium with HEPES buffer supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 50 U/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin and 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen). Cell lines HT1080 FUSA-GFP, HT1080 DDIT3-GFP and HT1080 FUS-DDIT3-GFP were generated by plasmid transfection of HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells as described elsewhere [8]. G418 (200 μg/ml) was constantly added to cell lines HT1080 FUSA-GFP, HT1080 DDIT3-GFP and HT1080 FUS-DDIT3-GFP to ensure stable expression of GFP constructs in the cell population. In a growth inhibition assay, FLT1-blocking antibody AF 321 (R&D systems) was added to MLS cells precultured in 4% fetal bovine serum for 14 hours in 96 well plates as described [12]. The cultures were visually analyzed by light microscopy after 72 hours of incubation. Flt-1 siRNA (sc-29319), PGF siRNA (sc-44027) and control siRNA-A (sc-37007) were transfected into cells using the siRNA Transfection Reagent (sc-29528, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) according to instructions supplied by the manufacturer.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA was prepared with the RNeasy lipid tissue kit (Qiagen) from an abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue biopsies of healthy individuals and from isolated adipocytes as previously described [13]. Acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction was used to isolate total RNA in representative tumor tissue from patients diagnosed with myxoid liposarcoma. Total RNA of cultured cells was isolated using QIAshredder and RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). RNA concentrations were measured with the NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer. cDNA was generated using a QuantiTect Reverse transcription kit (Qiagen) or alternatively using oligo dT primers and Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Real-time PCR was performed using a 7500 Fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) with SYBR Green detection (Qiagen). Formation of expected PCR products were confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis and melt curve analysis. Gene expression data was normalized against ACTB and GAPDH expression by geometric averaging [14]. Independent samples t-test was used to compare FLT1 expression between stably transfected cells. The following primer pairs were used for quantitative real-time PCR (5'-3'): FLT1_F TCCCTTATGATGCCAGCAAGT, FLT1_R CCAAAAGCCCCTCTTCCAA; PGF_F GTTCAGCCCATCCTGTGTCT, PGF_R AACGTGCTGAGAGAACGTCA; VEGFA_F CATCCTGTGTGCCCCTGA, VEGFA_R TTGTCTTGCTCTATCTTTCTTTGG; VEGFB_F AGTGCTGTGAAGCCAGACA, VEGFB_R GGAGTGGGATGGGTGATG; ACTB_F GCCGTCTTCCCCTCCATC, ACTB_R GCCTCGTCGCCCACATAG; GAPDH_F TCAGCCGCATCTTCTTTTG, GAPDH_R GACTCCGACCTTCACCTTC.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

Formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tissue samples were obtained, prepared and analyzed according to routine pathology protocols as part of clinical diagnostics at the Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden. Sections were mounted on glass slides, deparaffinated in xylol and stained as previously described [15] with primary antibodies for FLT1 (C-17, sc-316, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and VEGF receptor 1 (ab2350, Abcam). Human normal organs and various cancers tissue arrays (Super Bio Chips) containing 59 and 60 core biopsies per slide were stained as above. Angiosarcoma tissue sections were used as positive controls for the FLT1 staining. Negative controls were performed by omitting primary antibodies. For immunofluorescence studies, cells were grown in flaskettes, rinsed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and fixed for 20 minutes in 4% formaldehyde in PBS. Fixed cells were stained with antiserum for FLT1 (C-17, sc-316, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and PGF (ab9542, Abcam) and visualized using goat anti-rabbit Cy3-conjugated secondary antibodies (Dako). Slides were mounted using Prolong Gold antifade with DAPI (Molecular Probes) and allowed to cure overnight. Cellular fluorescence was imaged using a Zeiss LSM510 META confocal microscope system.

Western blot

Cellular nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were isolated using a PARIS kit (Ambion) according to the instructions by the manufacturer. Protein concentrations in fractions were determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Pierce) and diluted for equal loading on gels. Samples were mixed with 4X LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen), 10% 0.5 M dithiothreitol and run on NuPage 4-12% Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen). Proteins were blotted onto PVDF membranes (Immobilon) and probed with antibodies for FLT1 (C-17, sc-316, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Lamin A (133A2, ab8980, Abcam) and GAPDH (mAbcam 9484, Abcam). Bands were visualized by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies by chemiluminscent detection (SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate, Pierce). Chemiluminscent membranes were imaged using a LAS-4000 imaging system (Fujifilm).

Proliferation assay

Tumor cells were seeded out in wells of black walled/clear bottom 96-well plates (BD Falcon) and allowed to adhere overnight. The following day, VEGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) II or III (Calbiochem) were added in a concentration range of 0 to 10 μM. After 72 hours, cells were subjected to multiple freeze-thaw lyses at -80°C and 37°C, respectively, where after cell proliferation relative to untreated control cells was assayed with a CyQuant Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (Molecular Probes) using a Wallac 1420 multilabel counter (PerkinElmer). Independent samples t-test was used to evaluate differences between wells.

Results and Discussion

Inspection of previously collected microarray data [8] identified FLT1 as a candidate downstream target gene for FUS-DDIT3. FLT1 encodes the Fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (also called vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1, VEGFR1) reported to be involved in autocrine growth stimulatory loops in other sarcoma types [12]. Here we report that HT1080 human fibrosarcoma cells stably transfected with FUS-DDIT3 express FLT1 transcripts more than 20 times stronger than the original HT1080 cells (Figure 1). In addition, DDIT3-transfected HT1080 cells showed minor but significant (< 3 times) increase in FLT1 expression whereas HT1080 cells transfected with the 5' part of FUS showed slightly downregulated FLT1 expression. Quantitative PCR (QPCR) analysis also revealed that three tested MLS-derived cell lines expressed high levels of FLT1 transcripts, further indicating that FLT1 is expressed in FUS-DDIT3 carrying cells (Figure 1). However, transient transfection of HT1080 cells with FUS-DDIT3 failed to induce an increased FLT1 expression during a 48 hour observation period (Additional file 1). This indicates that transcription of FLT1 is not a direct target of FUS-DDIT3. Instead, the change in FLT1 expression could be an indirect effect of FUS-DDIT3 expression. The FUS-DDIT3 protein has the capacity to reprogram HT1080 cells to a liposarcoma-like phenotype by hijacking parts of normal adipose tissue development [8, 16]. The induction of FLT1 transcription in FUS-DDIT3 expressing cells may thus be a part of this process. This explanation is further supported by QPCR analyses showing prominent expression of FLT1 transcripts in isolated normal adipocytes (Additional file 2).

Increased FLT1 transcription in FUS-DDIT3 expressing cell lines. Bars show mean relative FLT1 expression by quantitative real-time PCR analysis of three independent biological replicates compared to wild type HT1080 with FLT1 expression set to 1. The geometric mean of ACTB and GAPDH expression was used to normalize FLT1 expression between samples. Error bars show standard error of the mean. Asterisks indicate statistical significance with p < 0.01.

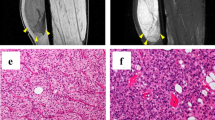

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis of human MLS tissues from nine cases and an MLS cell line xenografted in SCID mice showed strong, predominantly nuclear expression of the FLT1 protein (Figure 2a). The FLT1 nuclear stained tumor cells ranged from 60-80% in the nine investigated cases. No correlation between FLT1 staining and diagnosis (MLS or RCLS) were found. Immunofluorescence analysis of in vitro cultured MLS-derived cell lines 402-91 (Figure 2b) and 2645-94 (not shown), also showed a nuclear FLT1 localization. IHC staining of angiosarcoma tissue showed a cytoplasmic FLT1 staining in agreement with earlier reports [17] (Figure 2a). Indistinguishable results were obtained with two different antibodies for FLT1.

Nuclear FLT1 localization in MLS tumors and cultured MLS cells. (a) Immunohistochemical analysis of FLT1 expression in tissue sections of a representative MLS tumor and in an MLS 402-91 SCID mouse xenograft. Brown staining indicates FLT1 expression while blue staining shows negatively staining nuclei. Cytoplasmic FLT1 expression in angiosarcoma was used as a positive control. (b) FLT1 expression in cultured MLS 402-91 cells analyzed by immunofluorescence. The merge image shows nuclear DAPI staining in blue. Scale bar indicates 10 μm. (c) Western blot analysis of nuclear (N) and cytoplasmic (CP) fractions of MLS 402-91 cells. Lamin A was used as a control for the nuclear fraction and GAPDH was used as control for the cytoplasmic fraction.

The nuclear localization of FLT1 in MLS/RCLS was surprising since the protein is commonly reported a cytoplasmic or plasma membrane bound protein [18]. To further probe the cellular distribution of the FLT1 protein, we prepared nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts from the MLS-derived cell line MLS 402-91. Western blot analysis of these extracts with an FLT1 specific antibody showed that anti-FLT1 reactive proteins were enriched in the nuclear fraction (Figure 2c). The western blot results thus confirmed the nuclear localization of FLT1 protein in MLS cells. The migration difference detected between nuclear and cytoplasmic FLT1 (Figure 2c) could be due to different ionic strengths of the extraction buffers used for fractionation but may well be a result of post-translational modifications of nuclear FLT1 proteins.

These results prompted a further investigation as to whether FLT1 has a nuclear localization in other tumor types and in normal tissues. IHC analysis of tissue arrays containing 59 normal and 60 tumor-derived tissues showed a strong nuclear FLT1 expression in more than 90% of the tumor cells in 1/1 pancreatic carcinoma and in 1/3 ovary carcinomas (Figure 3a). Nuclear staining was also observed in several normal cell types, indicating that this localization of FLT1 is not restricted to tumor cells (Figure 3a). Most notably, FLT1 antibodies stained the nuclei of adipocytes, suggesting that nuclear FLT1 expression is a normal feature of this cell type. In addition, FLT1 antibodies stained the nuclei of normal skin-derived cultured F470 fibroblasts but with a more prominent cytoplasmic staining compared to the MLS cells (Figure 3b). The observation that FLT1 has a nuclear localization in some tissues may indicate additional, yet unknown, functions for this protein. Nuclear expression of FLT1 has also been reported in endothelial cells and in these cells FLT1 activation was necessary for growth and survival [19]. Nuclear localization of other receptor tyrosine kinases and specific functions in this compartment has previously been reported [20–23]. In MLS/RCLS and in normal adipocytes the nuclear expression may be important for maintenance of cell lineage/differentiation through phosphorylation/activation of specific chromatin components or transcription factors.

Nuclear FLT1 expression in malignant and normal cells. (a) Immunohistochemical analysis of FLT1 expression in cancerous and normal tissues. Brown staining indicates FLT1 expression while blue staining shows negatively staining nuclei. (b) Immunofluorescence analysis of FLT1 expression in cultured human fibroblasts. The merge image shows nuclear DAPI staining in blue. Scale bar indicates 10 μm.

Further inspection of array data suggested that PGF, encoding placental growth factor (PGF), a ligand of FLT1, is transcribed in MLS cells. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of MLS-derived cell lines showed that PGF expression was elevated in these cells compared with normal adipocytes (Figure 4a). The other FLT1 ligands VEGFA and VEGFB were expressed in cultured MLS cells but to a much lower degree than in adipocytes. In addition, the MLS cell lines showed PGF expression detected by immunofluorescence analysis (Figure 4b). In contrast to MLS cell lines, three MLS tumors showed a much more heterogenous expression of PGF, VEGFA and VEGFB but all tumors expressed PGF to some degree (Figure 4c). These results suggest differences of in vivo and in vitro ligand expression. Still, in light of our results, we hypothesize that autocrine circuits are operating in MLS cells. Such autocrine loops involving FLT1 have been reported to contribute to growth and survival of tumor cells [12, 24, 25] and to regulate differentiation of normal cell types [26, 27]. We tested for the presence of a possible FLT1 autocrine growth stimulatory loop in MLS cell line 402-91 by using an FLT1-blocking antibody reported to inhibit the growth of cells that are dependent on FLT1 signaling [12]. Incubation with this antibody failed however to affect growth or survival of the MLS cells. Though, receptor-targeted antibodies may be ineffective if the receptor and ligand interacts inside of the plasma membrane, which could be the case here. Such intracrine growth stimulatory circuits were recently reported for FLT1 in mammary carcinoma cells [28]. To test for an intracrine circuit in MLS/RCLS cells, knockdown experiments using siRNAs against FLT1 and PGF mRNA were attempted. As previously reported for knockdown experiments in MLS/RCLS cells [29], we were not able to achieve efficient knockdown of FLT1 or its ligand gene PGF. Instead we employed two specific inhibitors of FLT1 kinase activity (TKIs) in proliferation assays of MLS cell lines. None of the kinase inhibitors caused any decrease in cell numbers within the concentration range where they have shown specific inhibition of FLT1 activity [30, 31] (Figure 5). Thus, it is not likely that FLT1 and a probable autocrine/intracrine loop has a role in survival or proliferation in MLS cells but may contribute to the liposarcoma phenotype. Treatment with the TKIs gave no effect on the expression or localization of FLT1 in the MLS cells. Thus, the nuclear localization appears not to be related to the phosphorylation status of FLT1.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of PGF , VEGFA and VEGFB expression in FUS-DDIT3 expressing cell lines and tumors. (a) Bars show fold difference in ligand expression compared to adipocytes with a relative expression set to 1. Error bars show standard error of the mean (b) Immunofluorescence analysis of PGF expression in MLS 402-91. The merge image shows nuclear DAPI staining in blue. Scale bar indicates 10 μm. (c) Bars show relative expression of ligand mRNA in normal adipose tissue and in three MLS tumors. The geometric mean of ACTB and GAPDH expression was used to normalize gene expression between samples. Error bars show standard error of the mean.

Proliferation of tumor cells treated with VEGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Cells were treated with indicated concentrations of drugs for 72 hours and relative cell proliferation was assayed in comparison to untreated control cells. Bars show means of three biological replicates and error bars show standard error of the mean. Asterisks indicate significant inhibition of proliferation with p < 0.01.

Conclusions

We conclude that upregulation of FLT1 in MLS/RCLS is an indirect downstream effect of the liposarcoma fusion oncogene FUS-DDIT3 and that FLT1 is expressed as a nuclear protein both in MLS/RCLS lipoblasts and in normal adipocytes. The nuclear expression of FLT1 in adipocytes and other normal cell types suggest that this receptor tyrosine kinase has cell type specific functions in the nuclear compartment. Most likely these involve maintenance of cell lineage through phosphorylation of target proteins residing in the nucleus. The expression of FLT1 ligand genes PGF, VEGFA and VEGFB in MLS/RCLS cells and in normal adipocytes further indicates the presence of possible autocrine or intracrine loops. The importance of FLT1, PGF, VEGFA and VEGFB expression and their functions in MLS/RCLS tumor development remain unclear but our results point out this receptor/ligand system as operational in MLS/RCLS and as such a potential target for intervention in this tumor type.

Abbreviations

- CHOP:

-

CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein homologous protein

- DDIT3:

-

DNA-damage-inducible transcript 3

- FLT1:

-

Fms-like tyrosine kinase 1

- FUS:

-

fusion (involved in t(12; 16) in malignant liposarcoma)

- GADD153:

-

Growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible protein 153

- GFP:

-

green fluorescent protein

- IHC:

-

immunohistochemistry

- MLS/RCLS:

-

myxoid/round-cell liposarcomas

- PGF:

-

placental growth factor

- QPCR:

-

quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- siRNA:

-

short interfering RNA

- TKI:

-

tyrosine kinase inhibitor

- TLS:

-

translocated in liposarcoma

- VEGFR1:

-

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1

References

Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F: World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. 2002, IARC Press: Lyon

Andersson MK, Stahlberg A, Arvidsson Y, Olofsson A, Semb H, Stenman G, Nilsson O, Aman P: The multifunctional FUS, EWS and TAF15 proto-oncoproteins show cell type-specific expression patterns and involvement in cell spreading and stress response. BMC Cell Biol. 2008, 9: 37-10.1186/1471-2121-9-37.

Aman P, Ron D, Mandahl N, Fioretos T, Heim S, Arheden K, Willen H, Rydholm A, Mitelman F: Rearrangement of the transcription factor gene CHOP in myxoid liposarcomas with t(12;16)(q13;p11). Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1992, 5 (4): 278-285. 10.1002/gcc.2870050403.

Crozat A, Aman P, Mandahl N, Ron D: Fusion of CHOP to a novel RNA-binding protein in human myxoid liposarcoma. Nature. 1993, 363 (6430): 640-644. 10.1038/363640a0.

Rabbitts TH, Forster A, Larson R, Nathan P: Fusion of the dominant negative transcription regulator CHOP with a novel gene FUS by translocation t(12;16) in malignant liposarcoma. Nat Genet. 1993, 4 (2): 175-180. 10.1038/ng0693-175.

Panagopoulos I, Hoglund M, Mertens F, Mandahl N, Mitelman F, Aman P: Fusion of the EWS and CHOP genes in myxoid liposarcoma. Oncogene. 1996, 12 (3): 489-494.

Perez-Losada J, Pintado B, Gutierrez-Adan A, Flores T, Banares-Gonzalez B, del Campo JC, Martin-Martin JF, Battaner E, Sanchez-Garcia I: The chimeric FUS/TLS-CHOP fusion protein specifically induces liposarcomas in transgenic mice. Oncogene. 2000, 19 (20): 2413-2422. 10.1038/sj.onc.1203572.

Engstrom K, Willen H, Kabjorn-Gustafsson C, Andersson C, Olsson M, Goransson M, Jarnum S, Olofsson A, Warnhammar E, Aman P: The myxoid/round cell liposarcoma fusion oncogene FUS-DDIT3 and the normal DDIT3 induce a liposarcoma phenotype in transfected human fibrosarcoma cells. Am J Pathol. 2006, 168 (5): 1642-1653. 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050872.

Riggi N, Cironi L, Provero P, Suva ML, Stehle JC, Baumer K, Guillou L, Stamenkovic I: Expression of the FUS-CHOP fusion protein in primary mesenchymal progenitor cells gives rise to a model of myxoid liposarcoma. Cancer Res. 2006, 66 (14): 7016-7023. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3979.

Sanchez-Garcia I, Rabbitts TH: Transcriptional activation by TAL1 and FUS-CHOP proteins expressed in acute malignancies as a result of chromosomal abnormalities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994, 91 (17): 7869-7873. 10.1073/pnas.91.17.7869.

Thelin-Jarnum S, Lassen C, Panagopoulos I, Mandahl N, Aman P: Identification of genes differentially expressed in TLS-CHOP carrying myxoid liposarcomas. Int J Cancer. 1999, 83 (1): 30-33. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19990924)83:1<30::AID-IJC6>3.0.CO;2-4.

Gee MF, Tsuchida R, Eichler-Jonsson C, Das B, Baruchel S, Malkin D: Vascular endothelial growth factor acts in an autocrine manner in rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines and can be inhibited with all-trans-retinoic acid. Oncogene. 2005, 24 (54): 8025-8037. 10.1038/sj.onc.1208939.

Jernas M, Palming J, Sjoholm K, Jennische E, Svensson PA, Gabrielsson BG, Levin M, Sjogren A, Rudemo M, Lystig TC, et al: Separation of human adipocytes by size: hypertrophic fat cells display distinct gene expression. FASEB J. 2006, 20 (9): 1540-1542. 10.1096/fj.05-5678fje.

Vandesompele J, De Preter K, Pattyn F, Poppe B, Van Roy N, De Paepe A, Speleman F: Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002, 3 (7): RESEARCH0034-10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034.

Olofsson A, Willen H, Goransson M, Engstrom K, Meis-Kindblom JM, Stenman G, Kindblom LG, Aman P: Abnormal expression of cell cycle regulators in FUS-CHOP carrying liposarcomas. Int J Oncol. 2004, 25 (5): 1349-1355.

Perez-Mancera PA, Bermejo-Rodriguez C, Sanchez-Martin M, Abollo-Jimenez F, Pintado B, Sanchez-Garcia I: FUS-DDIT3 prevents the development of adipocytic precursors in liposarcoma by repressing PPARgamma and C/EBPalpha and activating eIF4E. PLoS ONE. 2008, 3 (7): e2569-10.1371/journal.pone.0002569.

Nagura S, Katoh R, Miyagi E, Shibuya M, Kawaoi A: Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and VEGF receptor-1 (Flt-1) in Graves disease possibly correlated with increased vascular density. Hum Pathol. 2001, 32 (1): 10-17. 10.1053/hupa.2001.21139.

Decaussin M, Sartelet H, Robert C, Moro D, Claraz C, Brambilla C, Brambilla E: Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its two receptors (VEGF-R1-Flt1 and VEGF-R2-Flk1/KDR) in non-small cell lung carcinomas (NSCLCs): correlation with angiogenesis and survival. J Pathol. 1999, 188 (4): 369-377. 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199908)188:4<369::AID-PATH381>3.0.CO;2-X.

Zhang Z, Neiva KG, Lingen MW, Ellis LM, Nor JE: VEGF-dependent tumor angiogenesis requires inverse and reciprocal regulation of VEGFR1 and VEGFR2. Cell Death Differ. 2010, 17 (3): 499-512. 10.1038/cdd.2009.152.

Lo HW, Hung MC: Nuclear EGFR signalling network in cancers: linking EGFR pathway to cell cycle progression, nitric oxide pathway and patient survival. Br J Cancer. 2007, R16-20. 96 Suppl

Matsuda R, Takahashi T, Nakamura S, Sekido Y, Nishida K, Seto M, Seito T, Sugiura T, Ariyoshi Y, et al: Expression of the c-kit protein in human solid tumors and in corresponding fetal and adult normal tissues. Am J Pathol. 1993, 142 (1): 339-346.

Stachowiak MK, Maher PA, Joy A, Mordechai E, Stachowiak EK: Nuclear localization of functional FGF receptor 1 in human astrocytes suggests a novel mechanism for growth factor action. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1996, 38 (1): 161-165. 10.1016/0169-328X(96)00010-1.

Xie Y, Hung MC: Nuclear localization of p185neu tyrosine kinase and its association with transcriptional transactivation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994, 203 (3): 1589-1598. 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2368.

Das B, Yeger H, Tsuchida R, Torkin R, Gee MF, Thorner PS, Shibuya M, Malkin D, Baruchel S: A hypoxia-driven vascular endothelial growth factor/Flt1 autocrine loop interacts with hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha through mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 pathway in neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 2005, 65 (16): 7267-7275. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4575.

Wang Y, Xiao ZJ, Liu P, Yang C, Yang RC, Cai YL, Han ZC: Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors KDR and Flt1 in acute myeloid leukemia. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2003, 24 (5): 249-252.

Casella I, Feccia T, Chelucci C, Samoggia P, Castelli G, Guerriero R, Parolini I, Petrucci E, Pelosi E, Morsilli O, et al: Autocrine-paracrine VEGF loops potentiate the maturation of megakaryocytic precursors through Flt1 receptor. Blood. 2003, 101 (4): 1316-1323. 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2184.

Jacobsen KA, Al-Aql ZS, Wan C, Fitch JL, Stapleton SN, Mason ZD, Cole RM, Gilbert SR, Clemens TL, Morgan EF, et al: Bone formation during distraction osteogenesis is dependent on both VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 signaling. J Bone Miner Res. 2008, 23 (5): 596-609. 10.1359/jbmr.080103.

Lee TH, Seng S, Sekine M, Hinton C, Fu Y, Avraham HK, Avraham S: Vascular endothelial growth factor mediates intracrine survival in human breast carcinoma cells through internally expressed VEGFR1/FLT1. PLoS Med. 2007, 4 (6): e186-10.1371/journal.pmed.0040186.

Goransson M, Andersson MK, Forni C, Stahlberg A, Andersson C, Olofsson A, Mantovani R, Aman P: The myxoid liposarcoma FUS-DDIT3 fusion oncoprotein deregulates NF-kappaB target genes by interaction with NFKBIZ. Oncogene. 2009, 28 (2): 270-8. 10.1038/onc.2008.378.

Furet P, Bold G, Hofmann F, Manley P, Meyer T, Altmann KH: Identification of a new chemical class of potent angiogenesis inhibitors based on conformational considerations and database searching. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003, 13 (18): 2967-2971. 10.1016/S0960-894X(03)00626-7.

Nakamura K, Yamamoto A, Kamishohara M, Takahashi K, Taguchi E, Miura T, Kubo K, Shibuya M, Isoe T: KRN633: A selective inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 tyrosine kinase that suppresses tumor angiogenesis and growth. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004, 3 (12): 1639-1649.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2407/10/249/prepub

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Dr. Margareta Jernås and Dr. Lena Carlsson (University of Gothenburg) for normal adipocyte RNA. This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Cancer Society, Assar Gabrielssons Research Foundation and the Johan Jansson Foundation for Cancer Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

MG and PÅ conceived of the study. MKA, MG and PÅ designed the experiments. MKA, MG, AO, CA and PÅ performed research. MKA and PÅ wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12885_2009_2048_MOESM1_ESM.PDF

Additional file 1: FLT1 expression in transiently transfected cells. HT1080 cells were transiently transfected with a FUS-DDIT3 construct and FLT1 expression was analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR at time points indicated in the figure. GAPDH expression was used to normalize FLT1 expression. Error bars show standard error of the mean. (PDF 27 KB)

12885_2009_2048_MOESM2_ESM.PDF

Additional file 2: FLT1 expression in isolated normal adipocytes. Expression of FLT1 in HT1080 cells and isolated adipocytes by quantitative real-time PCR. The geometric mean of ACTB and GAPDH expression was used to normalize gene expression between samples. Error bars show standard error of the mean. (PDF 27 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Andersson, M.K., Göransson, M., Olofsson, A. et al. Nuclear expression of FLT1 and its ligand PGF in FUS-DDIT3 carrying myxoid liposarcomas suggests the existence of an intracrine signaling loop. BMC Cancer 10, 249 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-10-249

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-10-249