Abstract

Background

Recently, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) for cases versus controls using single nucleotide polymorphism microarray data have shown promising findings for complex neuropsychiatric disorders, including bipolar disorder (BD).

Methods

Here we describe a comprehensive genome-wide study of bipolar disorder (BD), cross-referencing analysis from a family-based study of 229 small families with association analysis from over 950 cases and 950 ethnicity-matched controls from the UK and Canada. Further, loci identified in these analyses were supported by pathways identified through pathway analysis on the samples.

Results

Although no genome-wide significant markers were identified, the combined GWAS findings have pointed to several genes of interest that support GWAS findings for BD from other groups or consortia, such as at SYNE1 on 6q25, PPP2R2C on 4p16.1, ZNF659 on 3p24.3, CNTNAP5 (2q14.3), and CDH13 (16q23.3). This apparent corroboration across multiple sites gives much confidence to the likelihood of genetic involvement in BD at these loci. In particular, our two-stage strategy found association in both our combined case/control analysis and the family-based analysis on 1q21.2 (closest gene: sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 gene, S1PR1) and on 1q24.1 near the gene TMCO1, and at CSMD1 on 8p23.2, supporting several previous GWAS reports for BD and for schizophrenia. Pathway analysis suggests association of pathways involved in calcium signalling, neuropathic pain signalling, CREB signalling in neurons, glutamate receptor signalling and axonal guidance signalling.

Conclusions

The findings presented here show support for a number of genes previously implicated genes in the etiology of BD, including CSMD1 and SYNE1, as well as evidence for previously unreported genes such as the brain-expressed genes ADCY2, NCALD, WDR60, SCN7A and SPAG16.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Bipolar disorder (BD), also known as manic-depressive illness, is a chronic and devastating psychiatric condition, affecting 0.5-1.6% of the general population across their lifetime [1]. The frequency of hospitalization, psychological impairment, family devastation and suicidal behaviour make BD a major public health concern [2, 3], with an estimated total annual societal cost of at least 45 billion dollars in North America [4]. It is characterized by the recurrence of manic and hypomanic episodes. Although the majority of BD sufferers experience a significant reduction in symptoms between episodes of illness, approximately 60% develop chronic interpersonal and occupational impairment, with the result of untreated illness usually generating major disability [1]. Comorbidity with other psychiatric illness such as alcohol or substance abuse may also exacerbate the long-term course of BD [1].

Family, twin and adoption studies provide strong evidence of the genetic predisposition to BD [5, 6], with heritability estimates typically in the region of 80%. The recurrence risk in siblings of a BD proband is ~8% (corresponding to a sibling relative risk compared with the general population of λS ~ 8), and for monozygotic (identical) co-twins the risk is ~ 60%.

Identification of susceptibility genes for BD is the first step on a path toward improved understanding of the pathogenesis of mood disorders,with much to offer including (a) more effective and better targeted treatments, (b) earlier recognition of individuals at risk, and (c) improved understanding of environmental factors [7–9]. Linkage study findings support the view that no variation within a single gene can explain the majority of cases of BD, and demonstrates features that are typical in studies of complex genetic disorders, such as: (1) No finding replicates in all data sets, (2) Modest levels of statistical significance and estimated effect sizes, and (3) Chromosomal regions of linkage are typically broad (often > 20–30 cM).

Recent advances in density and speed of high-throughput single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping along with a reduction in costs has provided researchers with an excellent opportunity to dissect the genetics of BD, under the hypothesis that common variants contribute to the disease. There has since been a wave of large genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of BD that have used high-density SNP microarrays to look for common shared genotypes and haplotypes. Although such studies seem to suffer from many of the same problems as the family-based whole genome scans performed using microsatellite markers, i.e. failure to replicate across different sample sets and a realization that much larger sample sizes are necessary, the use of standard SNPs and genotyping methodologies has allowed the pooling of data from large patient cohorts, and this has led to some exciting findings of possible susceptibility loci and genes such as DGKH, CACNA1C and ANK3[10] (reviewed in Lee et al., 2012).

In the current study, we utilized an alternative and, we believe, more efficient strategy, that used genotype data from more than 950 BD cases and 950 psychiatrically screened controls collected from two sites with identical ascertainment criteria and assessment methods - one in Canada, the other in the UK. As a source of independent validation, we have also analysed genome-wide genotype data from a Canadian cohort of small families.

Methods

Subject recruitment

For the total 1922 samples, there are 871 samples from Toronto constituting 431 cases (160 males and 271 females) and 440 controls (176 males and 264 females); there are 1051 samples from UK including 538 cases (180 males and 358 females) and 513 controls (192 males and 321 females). A breakdown of mean and median age at interview, age of onset (AOO), diagnostic subtype (BD I versus BD II), presence of psychotic symptoms, suicide attempt and family history of psychiatric disorders has been provided previously for both the Toronto and UK cohorts [11]. The 229 Toronto parent-offspring trio families, including 215 families with BD proband and both parents, and 14 families with BD proband and just 1 parent. Demographic information and ascertainment criteria for the family cohort have been reported previously [12].

From the CAMH, Toronto site BD individuals and unrelated healthy controls matched for age, gender and ethnicity were recruited. Inclusion criteria for patients: a) diagnosed with DSMIV/ICD 10 BD I or II; b) 18 years old or over; c) Caucasian, of Northern and Western European origin, and three out of four grandparents also N.W. European Caucasian. Exclusion criteria include: a) Use of intravenous drugs; b) Evidence of mental retardation; c) Related to an individual already in the study; d) Manias that only ever occurred in relation to or as a result of alcohol or substance abuse or dependence and/or medical illness; e) Have any manias as a result of a non-psychotropic substance. In this study, the SCAN interview (Schedule for Clinical Assessments in Neuropsychiatry) was used. SCAN was developed in the framework of the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Joint Project on Diagnosis and Classification of Mental Disorders Alcohol and Drug Related Problems [13]. Details on SCAN are available at http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/40356.

Using both SCAN and case note review, each case was assigned DSM-IV and ICD 10 diagnoses by two independent team members with extensive diagnostic experience according to lifetime consensus best-estimate diagnosis [14]. Lifetime occurrence of psychiatric symptoms was also recorded using the OPCRIT checklist modified for use with mood disorders [15].

Similar methods and criteria were also used to collect a sample of 538 BD cases and 513 controls in London at the Institute of Psychiatry [16] (as described in Gaysina et al., 2010).

Our third sample is an independent BD cohort)t of 229 parent/affected offspring trio families also collected in the Toronto area. Methods included recruitment from hospital clinics and through advertising, SCID-I interviews, and best estimate consensus diagnosis [17, 18].

Both studies were approved by local Research Ethics Committees (the CAMH Research Ethics Board (REB) in Toronto, and the College Research Ethics Committee (CREC) at King’s College London, and informed written consent was obtained from all participants.

Genotyping

Genome-wide genotyping was performed for the Toronto and London case/control cohorts using the IlluminaSentrix Human Hap550 BeadChip (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Data was extracted by the Illumina® Beadstudio software from data files created by the IlluminaBeadArray reader. Mainly, these were genotyped by Illumina Inc. (San Diego, CA, USA) however 280 samples (97 cases and 183 controls) from the Toronto cohort were genotyped at the Genome Quebec facility. For the Toronto parent-offspring trio family cohort, Affymetrix 5.0 arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) were used, and genotyped by the London Regional Genomics Centre (London, Ontario).

Sample and SNP quality control

After genotyping, the discovery cohort samples were subject to a battery of a quality control (QC) tests. Reported and genetic gender were examined using X-chromosome linked SNPs. Relatedness between samples, sample contaminations, mis-identification and duplications were tested using genome-wide identity-by-descent (IBD) estimation; inconsistent samples were dropped from the analysis. Separate QC was applied on the validation cohort including the 229 Toronto parent-offspring trio families.

SNPs were subject to QC before analysis. Samples and markers with call rates below 95% were excluded from analysis. We removed SNPs with minor allele frequencies below 1%. To minimize genotyping errors we excluded SNPs with p-value <10-5 for HWE of control samples. PLINK software was used for quality control steps described above [19].

Population stratification

Principal component analysis was conducted with EIGENSTRAT [20] on the discovery cohort with SNPs selected after QC filtering. To ensure the most homogeneous groups for association analysis, we excluded subjects with outliers defined by EIGENSTRAT [20]. Principal components (PCs) were selected based on analysis of the scree plot. For the genetic association analysis, the selected principal components were adjusted in the logistic regression model to correct for population stratification. We did not apply principle component analysis on the validation cohort since the family-based association tests are robust against population substructure [21].

Genotype imputation

Since the discovery and validation datasets were genotyped on different GWAS SNP platforms, and the validation dataset has a smaller number of SNPs, genotypes of the SNPs that are not in the validation cohort were imputed. Beagle V3.3.1 [22] was used for the trio family imputation using a trio reference panel (HapMap3 Phasing Data: ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/hapmap//phasing/2009-02_phaseIII/HapMap3_r2/CEU/TRIOS/[23]) as this has better accuracy than imputation using a phased reference panel [22]. Individual genotypes with probability less than 0.90 were not included. Hidden Markov models (HMMs) were used for the imputation [22].

Association analysis

The association analyses were first applied on the discovery cohort with only autosomal markers tested for association. Although we used an additive genetic model for primary analyses, we also explored dominant and recessive genetic models for sensitivity analysis. Logistic regression models were applied based on a genetic additive model. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated for the cases compared to the control group. The association, adjusting for principal components from the EIGENSTRAT analysis, was tested using multivariate logistic regression (SAS v9.2, Cary, NC). Association analysis on the validation cohort of trio families was performed using the transmission disequilibrium test (TDT) [24]. Power calculations for association analyses were performed using QUANTO [25, 26].

Exploratory analysis on combined discovery and validation datasets

Exploratory analysis was applied on the combined dataset of unrelated case control individuals and the trio family data. A hybrid method was applied to combine the distinct estimates from separate case control samples and parent-offspring trio families [27]. The estimates obtained from separate analyses are combined into an overall risk estimate and provided with the corresponding p-value. As an exploratory analysis, the combined analysis was applied on the SNPs that were nominally significant (p < 0.01) in both the discovery and validation analysis.

Overlap of data with other published GWAS studies

Analysis of microarray genotype data for a subset of the cases/control cohort (483 cases, 462 controls) from the Institute of Psychiatry, London has been included in several published GWAS meta-analysis reports, including the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium (WTCCC) 2007, Scott et al., 2009, and Sklar et al., 2011 [28–30]. Data from a subset of the Canadian cohort (334 cases and 257 controls) were also included in the meta-analyses published by Scott et al., 2009 and Sklar et al., 2011, and in a locus-specific replication analysis locus by McMahon et al., 2010 (3p21.1) [31] and Francks et al., 2010 (19q13) [32]. Thus, the current study includes 55 cases and 49 controls from the London cohort and 97 cases and 183 controls from the Toronto cohort that do not overlap with these studies. GWAS for the small families does not overlap with any published genome-wide study, and pathway analysis on these cohorts has not been published previously.

Pathway analysis

Our pathway analysis on the discovery cohort data followed that described by Beyene et al. [33]. For each SNP passing QC, we performed univariate SNP association analysis using logistic regression in PLINK. We selected SNPs that have nominal association (p < 0.01) from the discovery data association analysis. This includes 5111 SNPs.We obtained the nearest gene for each of the selected SNP from the Illumina SNP annotation file (HumanHap550Yv3_Gene_Annotation, available from icom.illumina.com) based on physical distance. The SNPs were mapped to 2155 genes. For each of the mapped genes, we obtained an aggregate summary measure based on individual values for SNPs assigned to this gene. Here we used the maximum of absolute summary measure over all SNPs mapped to the gene [33].

The aggregated summary measure was used to evaluate the significance of predefined pathways using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software (IPA, version 11904312). Briefly, for a given pathway, statistical significance of the pathway enrichment is calculated using a Fisher's exact test based on the number of genes annotated, number of genes represented in the input dataset, and the total number of genes being assessed in the experiment. A pathway was deemed significant if the adjusted p-value of enrichment was ≤ 0.05 (adjusted for multiple comparisons using a Benjamini-Hochberg correction [34]).

Results and discussion

To test the common variant hypothesis more comprehensively, we performed an unbiased genome-wide association study of common variation using the discovery dataset of 1922 case–control samples. Findings were validated using the independent family-based cohort. Quality-control (QC) procedures were applied to the 510,740 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the discovery dataset and 440,794 SNPs in the validation dataset.

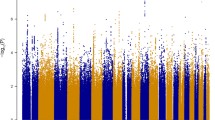

Population stratification

After applying QC filters, 502,877 common autosomal SNPs remained in the discovery dataset and 346,565 common autosomal SNPs remained in the validation dataset. To account for possible population stratification, principal component analysis was undertaken with EIGENSTRAT [20]. Five subjects were identified as population outliers and excluded from the analysis. Three principal components were selected based on scree plot. Additional analyses for population stratification were undertaken with each of the genetic markers adjusting for the three principle components. The final datasets included 912 cases and 903 controls in the discovery dataset and 224 families (636 individuals) in the validation dataset. The average genotyping rate in the remaining individuals was 99.7%. The logistic regression model was used for association analyses in the discovery cohort. In the discovery dataset, none of the p-values met the stringent and perhaps overly conservative Bonferroni correction for genome-wide significance (Figure 1A). The distribution of p-values examined in the discovery dataset demonstrated a close match to that expected for a null distribution except at the extreme tail of low p-values (Figure 2).

Quantile-Quantile (Q-Q) plot of p-values for the case control dataset. Note: The Q-Q plot measures deviation from the expected P-values. The diagonal (red) line represents the expected (null) distribution. The slight deviation of the observed values from expected values at the tail of the distribution is consistent with modest genetic effects.

Discovery dataset analysis

We computed the power of the 1815 samples in the discovery dataset. Given a prevalence of BD of 0.01, a SNP in LD (D' = 1) with a risk allele frequency 0.3, we have 76% power to detect significant association at p = 5.0E-7 under an additive model with strong effect size of OR 1.5. To detect an association with the same assumptions and at p = 5.0E-8 significance level, the statistical power is reduced to 0.61. With a moderate effect size of OR 1.3, the power to detect genome wide significant association (p < 5.0E-8) is very low. Despite no genome-wide significant association (p < 5.0E-8), 68 SNPs in our discovery dataset showed suggestive association with BD risk (p < 0.0001), many of which are replicating other GWAS findings for BD (Table 1 shows a subset of these SNPs with previous GWAS evidence for BD; the full set is given in Additional file 1). The most significant SNP was rs11787406, which is located just downstream of the gene PRSS5 on 8p23.1 (p = 2.35E-6). Also, among the top 68 SNPs we see 6 SNPs within the gene SYNE1 on 6q25, with lowest p = 3.02E-6 (plus a further 8 SNPs among the top 1000 SNPs; Additional file 1: Table S1; Figure 3). SNPs in this gene showed moderate association in the WTCCC study of ~2000 bipolar cases and ~3000 controls [28], with a genotypic p-value of 1.92E-05 for SNP rs2763025. Similarly, in a GWA meta-analysis [35] 14 SNPs within SYNE1 were identified with p value <9.0E-6. As the WTCCC study and Liu et al. meta-analyses included the case/control cohort from London, this cannot be presented as a completely independent observation, however the SYNE1 SNP rs17082664 also showed suggestive association in a combined analysis of WTCCC plus STEP-UCL and ED-DUB-STEP2 datasets (p = 3.6E-6), with much of the signal coming from the STEP-UCL study, which on its own gives p = 3E-4 [36]. A single SNP in ZNF659 on 3p24.3 was among the top 68 (with a further 4 SNPs among the top 1000; Additional file 1: Table S1). Sklar et al. [37] (no overlap with current datasets) also reported nominal association for this gene, with p = 3.25E-4 at rs259521. We also report 3 SNPs among the top 68 situated within the ZNF274 gene (rs4444432: p = 4.85E-6) on 19q13. However, this is someway distal to the nominal association for schizophrenia and psychosis reported by Francks et al. [32]. We also see suggestive association at rs4689410, within the PPP2R2C gene on 4p16.1 (p = 5.96E-6), which was previously reported to be associated to bipolar disorder [38, 39].

Plots for association for combined IoP/CAMH cohorts across the SYNE1 , and CSMD1 loci. Probability of significance of association for SNPs passing quality control is shown as –log10 of the P-value on the left hand Y-axis. Recombination rate as estimated from HapMap (http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) is plotted in light blue. Chromosomal position is plotted according to NCBI build 36/Hg18. The SNP with the strongest evidence for association at each locus is shown as a blue diamond.Correlation of linkage disequilibrium between SNPs and the blue diamond SNP, r2, is colour-coded, red indicating stronger LD.

In addition, a number of genes with no previous association to BD have multiple SNPs with suggestive association (Additional file 1: Table S4), including the brain-expressed genes, ADCY2, NCALD, WDR60, SCN7A and SPAG16.

Validation dataset analysis

We computed the power of the TDT in 224 trio families in our validation sample. Given a prevalence of BD of 0.01, a SNP in LD (D' = 1) with a risk allele frequency 0.3, we have 82% power to detect association at the p = 0.05 significance level under an additive model with a strong effect of OR 1.5. To detect an association with a moderate effect size of OR 1.3, the statistical power reduce to 0.58. 132 SNPs in the validation dataset showed suggestive association (p < 0.0001), with the lowest p-value at rs16873052 on 6p24.1, uncorrected p = 3.19×10-7(Figure 1B). Other SNPs showing suggestive association included SNPs within known candidate genes for BD, such as PDE4B (p = 7.45×10-5). PDE4B encodes a phosphodiesterase that binds directly with DISC1, and is critical for cyclic adenosine monophosphate signalling, which is linked to learning, memory, and mood [40], and shows association with SCZ [41–44], and to some degree with BD [44]. SNPs were identified with suggestive association at a number of other genes with plausible biological arguments for involvement in, and/or previous associations to BD, such as NRG3 (p = 5.53×10-6), GAD2 (p = 2.21×10-5), GRIK2 (p = 4.18×10-5), GABRG3 (p = 3.83×10-5), and the synapse-associated protein 102 gene, DLG3 (p = 5.31×10-5). In addition, a SNP in ATP2A2, the Darier disease gene (MIM#124200) also showed suggestive association (p = 2.67×10-5). Co-morbidity between Darier disease and BD has been known for some time [45], and linkage for BD to this locus has been reported in numerous studies [46–49]. Table 2 shows a subset of these 132 SNPs with previous evidence for BD or other neuropsychiatric disorders (the full set is given in Additional file 1).

Exploratory analysis on combined discovery and validation datasets

Thirteen SNPs were nominal significant in the combined case/control discovery cohort and the trio validation cohort datasets with joint analysis p < 0.01 (Table 3). A sign test for the same direction of effect between discovery cohort and trio validation cohort was significant (p < 0.001). Several SNPs in this list overlap with candidate genes of interest in non-overlapping studies. These include SNP rs1154037 in CSMD1, for which the intronic SNP rs4875310 was suggestive significant in the Sklar et al. 2008 study (p = 3.74×10-5), as well as other SNPs at CSMD1 in the Baum et al., 2008 study [50] (rs779105, NIMH cohort p = 0.0341, German cohort p = 0.0047; rs7812884, NIMH cohort p = 0.0012, German cohort p = 0.0103).

Pathway analysis

Using the set of 2155 genes identified by our association analysis, pathway analyses were performed with IPA. From the pathway analysis of the 2155 genes (1956 of them were mapped to the IPA database) with nominal associations, 30 pathways were significantly enriched for at a Benjamini-Hochberg corrected p-value of 0.05 (see Table 4). Specific pathways involved in bipolar disorder (such as Neuropathic Pain Signaling, CREB Signaling in Neurons, etc.) were amongst the ones identified as most significant (Table 4). Consequently, these results suggest that the genes identified by our association analysis have a high degree of biological relevance.

Conclusions

Our GWA study presented here represents a multi-staged analysis, combining case/control genome-wide genotype data from two “sister” studies with parallel recruitment strategies and identical genotyping platforms as a discovery set, and using a family-based cohort consisting mainly of trios as a validation set. We reported our results by using suggestive significance (p < 0.0001) and nominal significance (p < 0.01). This is based on the concern that the SNPs across the genome are not independent, so a simple Bonferroni adjustment may be too conservative. Although relatively few results were suggestive significant in both discovery and validation sets, several of the overlapping SNPs are in genes of much interest for neuropsychiatric disease. One SNP in particular (rs1154037) is located within the third intron of the CUB and Sushi multiple domains 1 gene (CSMD1), which has been implicated by at least two further (non-overlapping) BD GWA studies [37, 50]. CSMD1, which has also been associated with schizophrenia [51, 52], is a complement control-related gene, and supports the theory of diminished activity of immunity-related pathways in the brain as a disease mechanism for psychiatric disorders including BD [53]. CSMD1 protein can inhibit the deposition of complement component C3 in vitro[54], and thus impaired function may lead to impaired regulation of the classical complement cascade. Alternatively, it is also known that proteins involved in regulating complement control can also regulate synaptic function [55, 56]. Also of note, the neuropepetide Y gene, NYP, also identified by a nearby SNP in the joint discovery and validation analysis, was previously shown to be significantly down-regulated in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of psychosis patients [57], and in prefrontal cortex of BD subjects [58].

Analysis of associations from our discovery set shows strong support for the SYNE1 locus (Table 1; Figure 3), albeit not at genome-wide significance levels. SYNE1 has been implicated in a number of independent studies. Mutations of this gene are known as a cause for autosomal recessive spinocerebellar ataxia 8 (MIM 610743) and Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy 4 (MIM 612998). SYNE1 encodes a nesprin-1 component of a complex that links the cytoskeleton and nucleoskeleton (reviewed in [59]). However, several brain specific isoforms of rat Syne1 have been shown to localize to the postsynaptic side of synapses of glutamatergic neurons, and may be part of a mechanism of endocytosis of synaptic proteins, including glutamate receptors [60].

Our comparison with data from an independent BD GWAS from University College London showed joint suggestive significant loci at CDH13, PPP2R2C and IGFBP7 (McQuillin and Gurling, personal communication). Comparison with other published GWA studies for bipolar disorder, excluding those with partial overlap of subjects, appears to corroborate several loci and candidate genes, including CNTNAP5[50, 61], ZNF804A[62], ZNF659[37], SORCS2[50, 63, 64], and ZNF536[61]. A full list is provided in the Additional file 1: Table S2). CNTNAP5, encoding another neurexin-like protein, has also been linked with autism [65]. Interestingly, CDH13 was also suggestive significant in our validation set (rs7186123; p = 7.74E-5), however the odds ratio suggests this allele as protective, whereas for the suggestive significant SNPs at CDH13 in the discovery set the alleles appear mostly to be risk alleles (Additional file 1: Tables S1, S2 and S3).

Of the three zinc finger genes listed as loci showing suggestive significant association in our combined case/control study and in other bipolar GWA studies, little is known about the function, except for ZNF536 on chromosome 19p13.3, which is highly expressed in the developing brain, and in cerebral cortex, hippocampus and hypothalamus and is believed to be a negative regulator of neuronal differentiation [66].

Suggestive association was seen at SNP rs4689410 within the gene PPP2R2C in our study (p = 5.96E-6). This gene has been previously reported to be associated with BD [38, 39], and has also shown modest association in the UCL study, for SNP rs13122929 (p = 9.95E-4; McQuillin and Gurling, personal communication). Disruption of this gene may also be a cause of autosomal dominant intellectual disability (ID) [67]. This is one among a number of genes for which disruption may cause ID and for which common alleles may also be associated with risk for BD or SCZ (e.g. ANK3, TCF4 and NRXN1).

Interestingly, a number of well established GWAS candidate genes are not represented among our top 1000 p-values, including CACNA1C, ANK3 and DGKH[50, 64], or ODZ4 [30]. This could reflect differences in the population in terms of heterogeneity of phenotype or ethnicity, or an issue of insufficient power to detect an effect, or effects due to differences in method of ascertainment. Conversely, a number of genes in our validation set show multiple SNPs with suggestive association that have not been reported elsewhere (Additional file 1: Table S4), including the brain-expressed genes, ADCY2, NCALD, WDR60, SCN7A, SPAG16. It will be of much interest to see whether support for these genes, for which no phenotype has previously been reported (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man) [68], increases in BD meta-studies, once the sample size exceeds the tens of thousands.

In summary, the findings here support several key genetic associations to genes for BD, such as CSMD1, SYNE1.

References

American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 2000, USA: American Psychiatric Association, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR®), 4

Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, Goodwin FK: Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. JAMA. 1990, 264: 2511-2518. 10.1001/jama.1990.03450190043026.

Pini S, De Queiroz V, Pagnin D, Pezawas L, Angst J, Cassano GB, Wittchen HU: Prevalence and burden of bipolar disorders in European countries. Eur Psychopharmacol. 2005, 15: 425-434.

Sajatovic M: Bipolar disorder: disease burden. Am J Manag Care. 2005, 11 (Suppl 3): S80-S84.

McGuffin P, Katz R: The genetics of depression and manic-depressive disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1989, 155: 294-304.

Craddock N, Jones I: Genetics of bipolar disorder. J Med Genet. 1999, 36: 585-594.

Craddock N, Forty L: Genetics of affective (mood) disorders. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006, 14: 660-668. 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201549.

Kendler KS: Preparing for gene discovery: a further agenda for psychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999, 56: 554-555. 10.1001/archpsyc.56.6.554.

Rutter M, Plomin R: Opportunities for psychiatry from genetic findings. Br J Psychiatry. 1997, 171: 209-219. 10.1192/bjp.171.3.209.

Lee KW, Woon PS, Teo YY, Sim K: Genome wideassociation studies (GWAS) and copy number variation (CNV) studies of the major psychoses: what have we learnt?. Neurosci Bio behav Rev. 2012, 36: 556-557. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.09.001.

Tozzi F, Manchia M, Galwey NW, Severino G, Del Zompo M, McGuffin P, Kennedy JL, Reid I, Day R, Vincent J, Farmer A, Muglia P: Admixture analysis of bipolar disorder age at onset. Psychiatry Res. 2011, 185: 27-32. 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.11.025.

Mundo E, Zai G, Lee L, Parikh SV, Kennedy JL: The 5HT1Dbeta receptor gene in bipolar disorder: a family-based association study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001, 25: 608-613. 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00259-7.

Wing JK, Babor T, Brugha T, Burke J, Cooper JE, Giel R, Jablenski A, Regier D, Sartorius N: SCAN. Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990, 47: 589-593. 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810180089012.

Leckman JF, Sholomskas D, Thompson WD, Belanger A, Weissman MM: Best estimate of lifetime psychiatric diagnosis: a methodological study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982, 39: 879-883. 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290080001001.

McGuffin P, Farmer A, Harvey I: A polydiagnostic application of operational criteria in studies of psychotic illness. Development and reliability of the OPCRIT system. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991, 48: 764-770. 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810320088015.

Gaysina D, Cohen-Woods S, Chow PC, Martucci L, Schosser A, Ball HA, Tozzi F, Perry J, Muglia P, Kennedy JL, King N, Vincent JB, Parikh SV, Strauss J, Craig IW, McGuffin P, Farmer A: Association analysis of DAOA and DAO in bipolar disorder: results from two independent case–control studies. Bipolar Disord. 2010, 12: 579-581. 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00837.x.

Carter TD, Mundo E, Parikh SV, Kennedy JL: Early age at onset as a risk factor for poor outcome of bipolar disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2003, 37: 297-303. 10.1016/S0022-3956(03)00052-9.

Müller DJ, de Luca V, Sicard T, King N, Strauss J, Kennedy JL: Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene and rapid-cycling bipolar disorder: family-based association study. Br J Psychiatry. 2006, 189: 317-323. 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.010587.

Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PI, Daly MJ, Sham PC: PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007, 81: 559-575. 10.1086/519795.

Patterson N, Price AL, Reich D: Population Structure and Eigenanalysis. PLoS Genet. 2006, 2: e190-10.1371/journal.pgen.0020190.

Laird NM, Lange C: Family-based designs in the age of large-scale gene-association studies. Nat Rev Genet. 2006, 7: 385-394.

Browning B, Browning S: A unified approach to genotype imputation and haplotype-phase inference for large data sets of trios and unrelated individuals. Am J Hum Genet. 2009, 84: 210-223. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.01.005.

HapMap3 phasing data. ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/hapmap//phasing/2009-02_phaseIII/HapMap3_r2/CEU/TRIOS/

Spielman RS, McGinnis RE, Ewens WJ: Transmission test for linkage disequilibrium: the insulin gene region and insulindependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM). Am J Hum Genet. 1993, 52: 506-516.

Gauderman WJ: Sample size requirements for matched case–control studies of gene-environment interaction. Stat Med. 2002, 21: 35-50. 10.1002/sim.973.

Gauderman WJ: Candidate gene association studies for a quantitative trait, using parent-offspring trios. Genet Epidemiol. 2003, 25: 327-338. 10.1002/gepi.10262.

Kazeem GR, Farrall M: Integrating case–control and TDT studies. Ann Hum Genet. 2005, 69: 329-335. 10.1046/J.1469-1809.2005.00156.x.

Burton PR, Clayton DG, Cardon LR, Craddock N, Deloukas P, Duncanson A, Kwiatkowski DP, McCarthy MI, Ouwehand WH, Samani NJ, Todd JA, Donnelly P, Barrett JC, Davison D, Easton D, Evans DM, Leung HT, Marchini JL, Morris AP, Spencer CC, Tobin MD, Attwood AP, Boorman JP, Cant B, Everson U, Hussey JM, Jolley JD, Knight AS, Koch K, WellcomeTrust Case Control Consortium; Australo-Anglo-American Spondylitis Consortium(TASC), et al: Association scan of 14,500 nonsynonymous SNPs in four diseases identifies autoimmunity variants. Nat Genet. 2007, 39: 1329-1337. 10.1038/ng.2007.17.

Scott LJ, Muglia P, Upmanyu R, Guan W, Flickinger M, Kong X, Tozzi F, Li J, Burmeister M, Absher D, Thompson RC, Francks C, Meng F, Antoniades A, Southwick AM, Schatzberg A, Bunney W, Barchas J, Jones E, Day R, Matthews K, McGuffin P, Kennedy JL, Middleton L, Roses A, Watson SJ, Vincent J, Myers RM, Farmer A, Akil H, et al: Genome-wide association and meta-analysis of bipolar disorder in European ancestry samples. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009, 106: 7501-7506. 10.1073/pnas.0813386106.

Sklar P, Ripke S, Scott LJ, Andreassen OA, Cichon S, Craddock N, Edenberg HJ, Nurnberger JI, Rietschel M, Blackwood D, Corvin A, Flickinger M, Guan W, Mattingsdal M, McQuillin A, Kwan P, Wienker TF, Daly M, Dudbridge F, Holmans PA, Lin D, Burmeister M, Greenwood TA, Hamshere ML, Muglia P, Smith EN, Zandi PP, Nievergelt CM, McKinney R, Shilling PD, et al: Large-scale genome-wide association analysis of bipolar disorder identifies a new susceptibility locus near ODZ4. Nat Genet. 2011, 43: 977-983. 10.1038/ng.943.

McMahon FJ, Akula N, Schulze TG, Muglia P, Tozzi F, Detera-Wadleigh SD, Steele CJM, Breuer R, Strohmaier J, Wendland JR, Mattheisen M, Muhleisen TW, Maier W, Nothen MM, Cichon S, Farmer A, Vincent JB, Holsboer F, Preisig M, Rietschel M: The Bipolar Disorder Genetics (BiGs) Consortium: Meta-analysis of genome-wide association data detects a risk locus for major mood disorders on chromosome 3p21.1. Nat Genet. 2010, 42: 128-131. 10.1038/ng.523.

Francks C, Muglia P, Tozzi F, Farmer A, Vincent JB, Rujescu D, St Clair D: Population-based linkage analysis of schizophrenia and bipolar case–control cohorts identifies a potential susceptibility locus on 19q13. Mol Psychiatry. 2010, 15: 319-325. 10.1038/mp.2008.100.

Beyene J, Hu P, Hamid JS, Parkhomenko E, Paterson AD, Tritchler D: athway-based analysis of measures of explained variation in a genome-wide case–control association study of rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Proc. 2009, 3 (Suppl7): S128-

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y: Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B. 1995, 57: 289-300.

Liu Y, Blackwood DH, Caesar S, De Geus EJ, Farmer A, Ferreira MA, Ferrier IN, Fraser C, Gordon-Smith K, Green EK, Grozeva D, Gurling HM, Hamshere ML, Heutink P, Holmans PA, Hoogendijk WJ, Hottenga JJ, Jones L, Jones IR, Kirov G, Lin D, McGuffin P, Moskvina V, Nolen WA, Perlis RH, Posthuma D, Scolnick EM, Smit AB, Smit JH, Smoller JW, et al: Meta-analysis of genome-wide association data of bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2011, 16: 2-4. 10.1038/mp.2009.107.

Ferreira MA, O'Donovan MC, Meng YA, Jones IR, Ruderfer DM, Jones L, Fan J, Kirov G, Perlis RH, Green EK, Smoller JW, Grozeva D, Stone J, Nikolov I, Chambert K, Hamshere ML, Nimgaonkar VL, Moskvina V, Thase ME, Caesar S, Sachs GS, Franklin J, Gordon-Smith K, Ardlie KG, Gabriel SB, Fraser C, Blumenstiel B, Defelice M, Breen G, Gill M, et al: Collaborative genome-wide association analysis supports a role for ANK3 and CACNA1C in bipolar disorder. Nat Genet. 2008, 40: 1056-1058. 10.1038/ng.209.

Sklar P, Smoller JW, Fan J, Ferreira MA, Perlis RH, Chambert K, Nimgaonkar VL, McQueen MB, Faraone SV, Kirby A, de Bakker PI, Ogdie MN, Thase ME, Sachs GS, Todd-Brown K, Gabriel SB, Sougnez C, Gates C, Blumenstiel B, Defelice M, Ardlie KG, Franklin J, Muir WJ, McGhee KA, MacIntyre DJ, McLean A, VanBeck M, McQuillin A, Bass NJ, Robinson M, et al: Whole-genome association study of bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2008, 13: 558-569. 10.1038/sj.mp.4002151.

Borsotto M, Cavarec L, Bouillot M, Romey G, Macciardi F, Delaye A, Nasroune M, Bastucci M, Sambucy JL, Luan JJ, Charpagne A, Jouët V, Léger R, Lazdunski M, Cohen D, Chumakov I: PP2A-Bgamma subunit and KCNQ2 K+ channels in bipolar disorder. Pharmacogenomics J. 2007, 7: 123-132. 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500400.

Kim S, Webster MJ: Integrative genome-wide association analysis of cytoarchitectural abnormalities in the prefrontal cortex of psychiatric disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2011, 16: 452-461. 10.1038/mp.2010.23.

Porteous DJ, Thomson P, Brandon NJ, Millar JK: The genetics and biology of DISC1–an emerging role in psychosis and cognition. Biol Psychiatry. 2006, 60: 123-131. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.008.

Pickard BS, Thomson PA, Christoforou A, Evans KL, Morris SW, Porteous DJ, Blackwood DH, Muir WJ: The PDE4B gene confers sex-specific protection against schizophrenia. Psychiatr Genet. 2007, 17: 129-133. 10.1097/YPG.0b013e328014492b.

Fatemi SH, King DP, Reutiman TJ, Folsom TD, Laurence JA, Lee S, Fan YT, Paciga SA, Conti M, Menniti FS: PDE4B polymorphisms and decreased PDE4B expression are associated with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008, 101: 36-49. 10.1016/j.schres.2008.01.029.

Guan F, Zhang C, Wei S, Zhang H, Gong X, Feng J, Gao C, Su R, Yang H, Li S: Association of PDE4B polymorphisms and schizophrenia in Northwestern Han Chinese. Hum Genet. 2012, 131: 1047-1056. 10.1007/s00439-011-1120-8.

Kähler AK, Otnaess MK, Wirgenes KV, Hansen T, Jönsson EG, Agartz I, Hall H, Werge T, Morken G, Mors O, Mellerup E, Dam H, Koefod P, Melle I, Steen VM, Andreassen OA, Djurovic S: Association study of PDE4B gene variants in Scandinavian schizophrenia and bipolar disorder multicenter case–control samples. Am J Med Genet Part B. 2010, 153B: 86-96.

Craddock N, McGuffin P, Owen M: Darier's disease cosegregating with affective disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1994, 165: 272-

Ewald H, Mors O, Flint T, Kruse TA: Linkage analysis between manic depressive illness and the region on chromosome 12q involved in Darier'sdisease. Psychiatr Genet. 1994, 4: 195-200. 10.1097/00041444-199400440-00001.

Dawson E, Parfitt E, Roberts Q, Daniels J, Lim L, Sham P, Nöthen M, Propping P, Lanczik M, Maier W, Reuner U, Weissenbach J, Gill M, Powell J, McGuffin P, Owen M, Craddock N: Linkage studies of bipolar disorder in the region of the Darier'sdisease gene on chromosome 12q23-24.1. Am J Med Genet. 1995, 60: 94-102. 10.1002/ajmg.1320600203.

Ewald H, Degn B, Mors O, Kruse TA: Significant linkage between bipolar affective disorder and chromosome 12q24. Psychiatr Genet. 1998, 8: 131-140. 10.1097/00041444-199800830-00002.

Jones I, Jacobsen N, Green EK, Elvidge GP, Owen MJ, Craddock N: Evidence for familial cosegregation of major affective disorder and genetic markers flanking the gene for Darier's disease. Mol Psychiatry. 2002, 7: 424-427. 10.1038/sj.mp.4000989.

Baum AE, Akula N, Cabanero M, Cardona I, Corona W, Klemens B, Schulze TG, Cichon S, Rietschel M, Nöthen MM, Georgi A, Schumacher J, Schwarz M, AbouJamra R, Höfels S, Propping P, Satagopan J, Detera-Wadleigh SD, Hardy J, McMahon FJ: A genome-wide association study implicates diacylglycerol kinase eta (DGKH) and several other genes in the etiology of bipolar disorder.Mol Psychiatry. 2008, 13: 197-207. 10.1038/sj.mp.4002012.

Håvik B, Le Hellard S, Rietschel M, Lybæk H, Djurovic S, Mattheisen M, Mühleisen TW, Degenhardt F, Priebe L, Maier W, Breuer R, Schulze TG, Agartz I, Melle I, Hansen T, Bramham CR, Nöthen MM, Stevens B, Werge T, Andreassen OA, Cichon S, Steen VM: The complement control-related genes CSMD1 and CSMD2 associate to schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2011, 70: 35-42. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.01.030.

Kwon E, Wang W, Tsai LH: Validation of schizophrenia-associated genes CSMD1, C10orf26, CACNA1C and TCF4 as miR-137 targets. Mol Psychiatry. Epub ahead of print

Munkholm K, Vinberg M, VedelKessing L: Cytokines in bipolar disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2013, 144: 16-27. 10.1016/j.jad.2012.06.010.

Kraus DM, Elliott GS, Chute H, Horan T, Pfenninger KH, Sanford SD, Foster S, Scully S, Welcher AA, Holers VM: CSMD1 is a novel multiple domain complement-regulatory protein highly expressed in the central nervous system and epithelial tissues. J Immunol. 2006, 176: 4419-4430.

Gunnersen JM, Kim MH, Fuller SJ, De Silva M, Britto JM, Hammond VE, Davies PJ, Petrou S, Faber ES, Sah P, Tan SS: Sez-6 proteins affect dendritic arborization patterns and excitability of cortical pyramidal neurons. Neuron. 2001, 56: 621-639.

Gendrel M, Rapti G, Richmond JE, Bessereau JL: A secreted complement- control-related protein ensures acetylcholine receptor clustering. Nature. 2009, 461: 992-996. 10.1038/nature08430.

Choi KH, Elashoff M, Higgs BW, Song J, Kim S, Sabunciyan S, Diglisic S, Yolken RH, Knable MB, Torrey EF, Webster MJ: Putative psychosis genes in the prefrontal cortex: combined analysis of gene expression microarrays. BMC Psychiatry. 2008, 8: 87-10.1186/1471-244X-8-87.

Caberlotto L, Hurd YL: Reduced neuropeptide Y mRNA expression in the prefrontal cortex of subjects with bipolar disorder. Neuroreport. 1999, 10: 1747-1750. 10.1097/00001756-199906030-00022.

Rajgor D, Mellad JA, Autore F, Zhang Q, Shanahan CM: Multiple novel nesprin-1 and nesprin-2 variants act as versatile tissue-specific intracellular scaffolds. PLoS One. 2012, 7: e40098-10.1371/journal.pone.0040098.

Cottrell JR, Borok E, Horvath TL, Nedivi E: CPG2: a brain- and synapse-specific protein that regulates the endocytosis of glutamine receptors. Neuron. 2004, 44: 677-690.

Djurovic S, Gustafsson O, Mattingsdal M, Athanasiu L, Bjella T, Tesli M, Agartz I, Lorentzen S, Melle I, Morken G, Andreassen OA: A genome-wide association study of bipolar disorder in Norwegian individuals, followed by replication in Icelandic sample. J Affect Disord. 2010, 126: 312-316. 10.1016/j.jad.2010.04.007.

O'Donovan MC, Craddock N, Norton N, Williams H, Peirce T, Moskvina V, Nikolov I, Hamshere M, Carroll L, Georgieva L, Dwyer S, Holmans P, Marchini JL, Spencer CC, Howie B, Leung HT, Hartmann AM, Möller HJ, Morris DW, Shi Y, Feng G, Hoffmann P, Propping P, Vasilescu C, Maier W, Rietschel M, Zammit S, Schumacher J, Quinn EM, Schulze TG, et al: Identification of loci associated with schizophrenia by genome-wide association and follow-up. Nat Genet. 2008, 40: 1053-1055. 10.1038/ng.201.

Christoforou A, McGhee KA, Morris SW, Thomson PA, Anderson S, McLean A, Torrance HS, Le Hellard S, Pickard BS, StClair D, Muir WJ, Blackwood DH, Porteous DJ, Evans KL: Convergence of linkage, association and GWAS findings for a candidate region for bipolar disorder and schizophrenia on chromosome 4p. Mol Psychiatry. 2011, 16: 240-242. 10.1038/mp.2010.25.

Ollila HM, Soronen P, Silander K, Palo OM, Kieseppä T, Kaunisto MA, Lönnqvist J, Peltonen L, Partonen T, Paunio T: Findings from bipolar disorder genome-wide association studies replicate in a Finnish bipolar family-cohort. Mol Psychiatry. 2009, 14: 351-353. 10.1038/mp.2008.122.

Pagnamenta AT, Bacchelli E, de Jonge MV, Mirza G, Scerri TS, Minopoli F, Chiocchetti A, Ludwig KU, Hoffmann P, Paracchini S, Lowy E, Harold DH, Chapman JA, Klauck SM, Poustka F, Houben RH, Staal WG, Ophoff RA, O'Donovan MC, Williams J, Nöthen MM, Schulte-Körne G, Deloukas P, Ragoussis J, Bailey AJ, Maestrini E, Monaco AP, International Molecular Genetic Study Of Autism Consortium: Characterization of a family with rare deletions in CNTNAP5 and DOCK4 suggests novel risk loci for autism and dyslexia. Biol Psychiatry. 2010, 68: 320-328. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.02.002.

Qin Z, Ren F, Xu X, Ren Y, Li H, Wang Y, Zhai Y, Chang Z: ZNF536, a novel zinc finger protein specifically expressed in the brain, negatively regulates neuron differentiation by repressing retinoic acid-induced gene transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 2009, 29: 3633-3643. 10.1128/MCB.00362-09.

Backx L, Vermeesch J, Pijkels E, de Ravel T, Seuntjens E, Van Esch H: PPP2R2C, a gene disrupted in autosomal dominant intellectual disability. Eur J Med Genet. 2010, 53: 239-243. 10.1016/j.ejmg.2010.06.006.

OMIM. http://omim.org/,

Purcell SM, Wray NR, Stone JL, Visscher PM, O'Donovan MC, Sullivan PF, Sklar P, International Schizophrenia Consortium: Common polygenic variation contributes to risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Nature. 2009, 460: 748-752.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2350/15/2/prepub

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank all subjects for their cooperation with the study. This study was supported through funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, MOP-172013. The collection of the case control cohorts was supported by funding from GlaxoSmithKline. We also wish to thank the following for their assistance and support for the data collection: Nicole King, Michael Sherman, Laura Miler, Pam Zuker, Masood Zanganeh, Mona Nouroozifar, Cara Morrison, Tricia Sicard, David Sibony, and Sajid Shaikh. The authors wish to acknowledge Alexandre Petit and Francois Bacot of the genotyping platform of the McGill University and Génome Québec Innovation Centre for their technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

At the time of the study, authors FT, PM and JF were employees of GlaxoSmithKline (GSK). FT is currently affiliated with GSK. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JBV, JS, JLK and WX conceived and designed the study. PM, FT designed the data collection with support for clinical data collection and analysis from PMc and AF. JF assisted with coordination of the sample and data collection. JS, SVP and GH assisted with the clinical data collection. WX and QC performed statistical procedures, with assistance in data analysis and interpretation from AN, JK, VD-L, AM and HMDG. JBV and WX drafted the manuscript with assistance from JK and SW-C. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12881_2013_1166_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Additional file 1: Table S1: SNPs from top 1000 from our combined CAMH/IoP GWAS for BPAD, for which at least one other non-overlapping GWAS also shows association at same gene. Table S2: Top 68 SNPs (showing suggestive association to BD: p < 0.0001) in our combined (CAMH and IoP) GWAS. Table S3. Top 132 SNPs (showing suggestive association to BD in our CAMH family cohort: p < 0.0001). Table S4: Listing suggestive significant genic SNPs for combined Toronto and London GWAS for which there are 4 or more suggestive significant SNPs among the top 1000, and for which no other positive reports have been published to date Figure S1: Scree plot of principal components (PCs) of the genotypes in the case–control samples. (DOCX 121 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, W., Cohen-Woods, S., Chen, Q. et al. Genome-wide association study of bipolar disorder in Canadian and UK populations corroborates disease loci including SYNE1 and CSMD1 . BMC Med Genet 15, 2 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2350-15-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2350-15-2