Abstract

Background

Primary study selection between systematic reviews is inconsistent, and reviews on the same topic may reach different conclusions. Our main objective was to compare systematic reviews on negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) regarding their agreement in primary study selection.

Methods

This retrospective analysis was conducted within the framework of a systematic review (a full review and a subsequent rapid report) on NPWT prepared by the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG).

For the IQWiG review and rapid report, 4 bibliographic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, The Cochrane Library, and CINAHL) were searched to identify systematic reviews and primary studies on NPWT versus conventional wound therapy in patients with acute or chronic wounds. All databases were searched from inception to December 2006.

For the present analysis, reviews on NPWT were classified as eligible systematic reviews if multiple sources were systematically searched and the search strategy was documented. To ensure comparability between reviews, only reviews published in or after December 2004 and only studies published before June 2004 were considered.

Eligible reviews were compared in respect of the methodology applied and the selection of primary studies.

Results

A total of 5 systematic reviews (including the IQWiG review) and 16 primary studies were analysed. The reviews included between 4 and 13 primary studies published before June 2004. Two reviews considered only randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Three reviews considered both RCTs and non-RCTs. The overall agreement in study selection between reviews was 96% for RCTs (24 of 25 options) and 57% for non-RCTs (12 of 21 options). Due to considerable disagreement in the citation and selection of non-RCTs, we contacted the review authors for clarification (this was not initially planned); all authors or institutions responded. According to published information and the additional information provided, most differences between reviews arose from variations in inclusion criteria or inter-author study classification, as well as from different reporting styles (citation or non-citation) for excluded studies.

Conclusion

The citation and selection of primary studies differ between systematic reviews on NPWT, particularly with regard to non-RCTs. Uniform methodological and reporting standards need to be applied to ensure comparability between reviews as well as the validity of their conclusions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Although systematic reviews are a valuable tool in the synthesis of evidence, they should be interpreted with caution [1]. The sharp rise in the number of systematic reviews published over the past decades has led to a concomitant increase in discordant results and conclusions between reviews on the same research question [2–5]. This has caused disputes between researchers and created difficulties for decision-makers in selecting appropriate health care interventions. Among other things, discordance between reviews may be caused by differences in primary study selection [6] due to variations in literature search strategies, selection criteria, and the application of selection criteria [2].

The Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (Institut für Qualität und Wirtschaftlichkeit im Gesundheitswesen, IQWiG) conducted a systematic review on the effectiveness and safety of negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) versus conventional wound therapy in patients with acute or chronic wounds. The NPWT technique aims to accelerate wound healing by placing a foam dressing in the wound and applying controlled subatmospheric pressure [7]. The German-language full review and a rapid report on studies subsequently published are available on the IQWiG website [8, 9]. In addition, an English-language journal article has been published [10].

An additional retrospective analysis was conducted in order to compare different systematic reviews on NPWT regarding their agreement in primary study selection. The review methodologies were also compared.

Methods

For the IQWiG review and rapid report, 4 bibliographic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, The Cochrane Library, and CINAHL) were searched to identify systematic reviews and primary studies on NPWT versus conventional wound therapy in patients with acute or chronic wounds. All databases were searched from inception to May 2005 (review) and between May 2005 and December 2006 (rapid report).

The multi-source search strategy and literature screening are described in detail elsewhere [8]. Eligible primary studies were randomised controlled trials (RCTs), as well as non-randomised controlled trials (non-RCTs) with a concurrent control group. Studies were classified as non-randomised if allocation concealment was viewed as inadequate [11]. Quasi-randomised studies were therefore classified as non-randomised. The intervention was categorised as NPWT if a medical device system identical or comparable to the vacuum-assisted closure (V.A.C.®) system was used. Studies were considered to be eligible only if publicly accessible full-text articles or other comprehensive study information (e.g. clinical study reports provided by manufacturers) were available.

For the present analysis, an identical and sufficiently large primary study pool, i.e. the pool of studies that could potentially be identified by all reviews, was required to ensure comparability between reviews. As a preliminary analysis showed that early reviews merely included 2 to 4 primary studies, only reviews published in or after December 2004 were considered.

Eligible reviews had to include data from completed primary studies on NPWT. Reviews were classified as systematic reviews (as opposed to narrative reviews) if multiple sources were searched (at least MEDLINE and The Cochrane Library), and the search strategy (including the search date) was documented [12].

Primary studies were eligible for inclusion only if they had been published before June 2004 and if the entry date of a study in a database preceded the date of the literature search of any systematic review analysed.

The methodology and primary study selection between reviews were compared, and the overall agreement in study selection between reviews was reported.

Only a summary of the reviews' quality assessment of primary studies and their conclusions on the effectiveness of NPWT is presented here, as the main focus of this paper was to compare the agreement in primary study selection between reviews.

Results

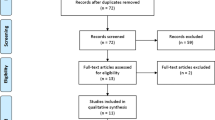

The flow charts of the selection of systematic reviews and primary studies are presented in Figures 1 and 2. Sixteen primary studies published before June 2004 were assessed in the present analysis [13–28]. A total of 5 eligible systematic reviews (the IQWiG review and 4 other systematic reviews) published between December 2004 and July 2006 were analysed [29–32]. Details on all reviews identified are shown in Table 1; the main reason for exclusion was failure to qualify as a systematic review.

The methods applied in the reviews included are presented in Tables 2 and 3. Regarding bibliographic databases, all reviews used MEDLINE, EMBASE, and The Cochrane Library, but the nursing database CINAHL was used only by IQWiG. The search terms applied varied between reviews. Regarding study design, the IQWiG review [8], as well as the reviews by Costa 2005 [30] and Pham 2006 [31] considered both RCTs and non-RCTs, while the reviews by Samson 2004 [29] and OHTAC 2006 [32] took only RCTs into account.

As the comparison of systematic reviews based on published information showed numerous inconsistencies, we decided to contact the authors of the other reviews for clarification (this was not initially planned). We received responses from all authors approached (or from other researchers at the publishing institutions). After reviewing the responses, it became clear that reporting styles for excluded studies differed between reviews. For example, the response by OHTAC stated that "it must be noted that we do not routinely cite or analyse studies that have been excluded from our EBAs (evidence-based analyses)" [personal communication]. It consequently became apparent that some studies we had initially classified as "not identified by other reviews" had actually been identified but excluded, and subsequently not reported. We therefore changed the classification of studies not cited in reviews to "not reported". In addition, the authors of reviews corrected or clarified published information (their comments are included in Tables 4, 5, 6); in this context we thank them for generously providing information.

Details of the primary study selection are presented according to the study classification by IQWiG in Tables 4 (5 RCTs), 5 (7 non-RCTs), and 6 (3 non-RCTs and 1 RCT excluded by IQWiG, but included by at least one other review).

The reviews included between 4 and 13 eligible primary studies published before June 2004. With regard to RCTs, the overall agreement in primary study selection between reviews was 96% (24 of 25 options) (Table 5).

More variations were noted concerning the selection of non-RCTs; the agreement between reviews considering both RCTs and non-RCTs was 57% (12 of 21 options). Of the 9 mismatches, according to published information and the information provided by authors or institutions, 7 were due to different inclusion criteria (e.g. language criteria), and 2 were due to variations in study classification (Table 5).

Four studies (3 non-RCTs and 1 RCT) were excluded by IQWiG but included by at least one other review. The reasons for exclusion were as follows: the study included historical controls (2 non-RCTs [13, 26]); the intervention applied was not comparable to the NPWT technique (1 non-RCT [14]); or an additional intervention was applied that may have affected the study outcomes (1 RCT [19]) (Table 6). Substantial variations in study selection were shown between reviews.

Only the IQWiG review included a meta-analysis (changes in wound size), which indicated an advantage in favour of NPWT. However, only a few trials with small sample sizes were analysed.

The overall quality of the primary studies was assessed in 3 of 5 reviews, and was in general classified as poor. All reviews concluded that the evidence base on NPWT was insufficient (Table 7).

Discussion

An analysis of 5 systematic reviews on NPWT showed differences (which mainly concerned non-RCTs) in the citation and selection of primary studies.

We would like to emphasize that by presenting these differences, we are not implying that the 4 other reviews identified were of inferior quality compared with the IQWiG review. Variations in the number of primary studies identified and selected are not surprising, as the reviews used different search strategies, literature sources, and inclusion criteria. After correspondence with the authors of the other reviews, many differences regarding the citation of primary studies could be attributed to different reporting styles (citation or non-citation) for excluded studies, not to the non-detection of studies in the literature searches.

Most differences in study selection resulted from variations in inclusion and exclusion criteria. For example, due to language restrictions, studies published in German were selected by IQWiG, but not by other reviews. Opinions on the relevance of language bias differ; a study published in 1997 comparing English and German-language publications concluded that English-language bias may be introduced in systematic reviews if they include only trials reported in English [33]. In contrast, a more recent publication noted that, for conventional medicinal interventions, language restrictions did not appear to bias estimates of effectiveness [34]. Moreover, for German-language publications on RCTs, it has been reported that German medical journals no longer play a role in the dissemination of trial results [35].

The inclusion criteria for primary study design were also inconsistent; 3 reviews (including the IQWiG review) considered both RCTs and non-RCTs, and 2 reviews considered only RCTs. The non-RCTs included in our analysis were non-randomised controlled intervention studies. However, there are many different study types that can be seen as non-RCTs (e.g., classical observational studies). The inclusion of non-RCTs in systematic reviews is inconsistent and controversial [36–40]. The validity of systematic reviews including non-RCTs may be affected by the differing susceptibility of RCTs and non-RCTs to selection bias [39], although it has been suggested that under certain conditions, estimates of effectiveness of non-RCTs may be valid if confounding is controlled for [40].

RCTs with adequately concealed allocation prevent selection bias and consequent distortions of treatment effects [41], and systematic reviews including RCTs represent the highest level of evidence for therapeutic interventions [42]. However, the quality and quantity of RCTs in surgical research is limited [43], and it has therefore been proposed not to base this type of research on RCTs alone [36, 44]. Indeed, for some topics, non-RCTs are the only evidence available [45].

As for NPWT, although this treatment is widely applied in clinical practice, particularly in chronic wounds, at the time the IQWiG systematic review on NPWT was being planned only few RCTs were available; moreover, these were of poor quality [29]. However, there has been a recent increase in published RCTs, and as several of them are ongoing, more publications can be expected in the near future. One HTA agency has already changed its policy from including both RCTs and non-RCTs in systematic reviews on NPWT to one of including solely RCTs [32]. We agree with other researchers that non-RCTs should only be performed when RCTs are infeasible or unethical [38], and that systematic reviews including non-RCTs should only be conducted when RCTs are not available [39]. However, we emphasize that this should not be generalized to recommend excluding all kinds of non-randomised studies from systematic reviews on any topic and for any outcome of interest.

The type of non-RCT considered also differed: IQWiG's precondition for inclusion was the existence of a concurrent control group; studies with a historical control group were excluded, as systematic bias may arise from time trends in the outcomes of study participants [38].

Moreover, variations in the classification of study design were noted between reviews. For example, David Sampson, one of the other review authors, stated: "In general, our definition of randomized trials was probably more inclusive than yours. We decided to be inclusive due to the small number of potentially relevant studies available at that time. Our goal was to evaluate the quality of a larger pool of included studies rather than exclude more studies, based on quality concerns, to create a smaller pool of included studies" [personal communication].

As subjective factors are involved in the preparation of systematic reviews, inter-author variation is inevitable [46]. The evaluation of inter-author variation has shown that differences particularly affect the classification of study design [46, 47]. One study showed that this was the case even when specific instructions and definitions were provided [47]. However, a recent analysis of the reproducibility of systematic reviews showed that, where authors were provided with guidelines for review preparation (including an algorithm to ensure that study designs were defined in a standardised manner), the overall reproducibility between reviews was good [48]. This finding emphasizes the relevance of standard reporting guidelines. The CONSORT statement on improving the quality of reporting for RCTs has been available for over a decade [49], and a revised version was published in 2001 [50]. In contrast, guidelines for non-RCTs are more recent [51, 52]. The introduction of uniform reporting standards for non-RCTs may improve the future quality of reporting and lead to a closer agreement in the primary study citation and selection of systematic reviews.

Even though the reviews analysed included different numbers and types of studies, all reviews reached similar conclusions. This may be explained by the fact that the overall quality of the data on NPWT is poor.

Conclusion

The citation and selection of primary studies differ between systematic reviews on NPWT, primarily with regard to non-RCTs. These differences arise from variations in review methodology and inter-author classification of study design, as well as from different reporting styles for excluded studies. Uniform methodological and reporting standards need to be applied to ensure comparability between reviews as well as the validity of their conclusions.

References

Hopayian K: The need for caution in interpreting high quality systematic reviews. BMJ. 2001, 323: 681-684. 10.1136/bmj.323.7314.681.

Jadad AR, Cook DJ, Browman GP: A guide to interpreting discordant systematic reviews. CMAJ. 1997, 156: 1411-1416. [http://www.cmaj.ca/cgi/reprint/156/10/1411?ck=nck]

Furlan AD, Clarke J, Esmail R, Sinclair S, Irvin E, Bombardier C: A critical review of reviews on the treatment of chronic low back pain. Spine. 2001, 26: E155-E162.

Hoving JL, Gross AR, Gasner D, Kay T, Kennedy C, Hondras MA, Haines T, Bouter LM: A critical appraisal of review articles on the effectiveness of conservative treatment for neck pain. Spine. 2001, 26: 196-205.

Jadad AR, McQuay HJ: Meta-analyses to evaluate analgesic interventions: a systematic qualitative review of their methodology. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996, 49: 235-243.

Bland M, Rodgers M, Fayter D, Sowden A, Lewin R: Agreement in primary study selection between systematic reviews. 2006, York, UK, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York, [http://www-users.york.ac.uk/~mb55/talks/meta_agree.pdf]

Argenta LC, Morykwas MJ: Vacuum-assisted closure: a new method for wound control and treatment: clinical experience. Ann Plast Surg. 1997, 38: 563-577.

Negative pressure wound therapy. Final report (German version). 2006, Cologne, Germany, Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG), [http://www.iqwig.de/download/N04-03_Abschlussbericht_Vakuumversiegelungstherapie_zur_Behandlung_von_Wunden..pdf]

Negative pressure wound therapy. Rapid report (German version). 2007, Cologne, Germany, Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG), [http://www.iqwig.de/download/N06-02_Rapid_Report_Vakuumversiegelungstherapie_von_Wunden.pdf]

Gregor S, Maegele M, Sauerland S, Krahn JF, Peinemann F, Lange S: Negative pressure wound therapy: a vacuum of evidence?. Arch Surg. 2008, 143: 189-196.

Jüni P, Altman DG, Egger M: Assessing the quality of randomised controlled trials. Systematic reviews in health care - meta-analysis in context. Edited by: Egger M, Davey Smith G and Altman DG. 2001, London, UK, BMJ Publishing Group, 87-108.

Higgins JPT GS: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 4.2.6 Updated September 2006. The Cochrane Library. 2006, Chichester, UK, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd

Catarino PA, Chamberlain MH, Wright NC, Black E, Campbell K, Robson D, Pillai RG: High-pressure suction drainage via a polyurethane foam in the management of poststernotomy mediastinitis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000, 70: 1891-1895.

Davydov IA, Abramov AI, Darichev AB: Khirurgiia (Mosk). 1994, 7-10. [Regulation of wound process by the method of vacuum therapy in middle-aged and aged patients], Reguliatsiia ranevogo protsessa u bol'nykh pozhilogo i starcheskogo vozrasta metodom vakuum-terapii,

Doss M, Martens S, Wood JP, Wolff JD, Baier C, Moritz A: Vacuum-assisted suction drainage versus conventional treatment in the management of poststernotomy osteomyelitis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002, 22: 934-938.

Eginton MT, Brown KR, Seabrook GR, Towne JB, Cambria RA: A prospective randomized evaluation of negative-pressure wound dressings for diabetic foot wounds. Ann Vasc Surg. 2003, 17: 645-649.

Ford CN, Reinhard ER, Yeh D, Syrek D, De Las MA, Bergman SB, Williams S, Hamori CA: Interim analysis of a prospective, randomized trial of vacuum-assisted closure versus the healthpoint system in the management of pressure ulcers. Ann Plast Surg. 2002, 49: 55-61.

Genecov DG, Schneider AM, Morykwas MJ, Parker D, White WL, Argenta LC: A controlled subatmospheric pressure dressing increases the rate of skin graft donor site reepithelialization. Ann Plast Surg. 1998, 40: 219-225.

Jeschke MG, Rose C, Angele P, Fuchtmeier B, Nerlich MN, Bolder U: Development of new reconstructive techniques: use of Integra in combination with fibrin glue and negative-pressure therapy for reconstruction of acute and chronic wounds. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004, United States, 113: 525-530.

Joseph E, Hamori CA, Bergman S, Roaf E, Swann NF, Anastasi GW: A prospective randomized trial of vacuum-assisted closure versus standard therapy of chronic nonhealing wounds. Wounds A Compendium of Clinical Research and Practice. 2000, 12: 60-67.

Kamolz LP, Andel H, Haslik W, Winter W, Meissl G, Frey M: Use of subatmospheric pressure therapy to prevent burn wound progression in human: first experiences. Burns. 2004, England, 30: 253-258.

McCallon SK, Knight CA, Valiulus JP, Cunningham MW, McCulloch JM, Farinas LP: Vacuum-assisted closure versus saline-moistened gauze in the healing of postoperative diabetic foot wounds. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2000, 46: 28-34.

Moues CM, Vos MC, van den Bemd GJ, Stijnen T, Hovius SE: Bacterial load in relation to vacuum-assisted closure wound therapy: a prospective randomized trial. Wound Repair Regen. 2004, United States, 12: 11-17.

Scherer LA, Shiver S, Chang M, Meredith JW, Owings JT: The vacuum assisted closure device: a method of securing skin grafts and improving graft survival. Arch Surg. 2002, 137: 930-934.

Schrank C, Mayr M, Overesch M, Molnar J, Henkel von Donnersmarck G, Mühlbauer W, Ninkovic M: Zentralbl Chir. 2004, 129 Suppl 1: S59-S61. [Results of vacuum therapy (V.A.C.(R)) of superficial and deep dermal burns], Ergebnisse der Vakuumtherapie (V.A.C.-Therapie) von oberflächlichen und tiefdermalen Verbrennungen,

Song DH, Wu LC, Lohman RF, Gottlieb LJ, Franczyk M: Vacuum assisted closure for the treatment of sternal wounds: the bridge between debridement and definitive closure. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003, 111: 92-97.

Wanner MB, Schwarzl F, Strub B, Zaech GA, Pierer G: Vacuum-assisted wound closure for cheaper and more comfortable healing of pressure sores: a prospective study. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2003, 37: 28-33.

Wild T, Stremitzer S, Budzanowski A, Rinder H, Tamandl D, Zeisel C, Holzenbein T, Sautner T: Zentralbl Chir. 2004, 129 Suppl 1: S20-S23. Abdominal Dressing" - A new method of treatment for open abdomen following secondary peritonitis], "Abdominal Dressing" - Eine neue Methode in der Behandlung des offenen Abdomens bei der sekundären Peritonitis,

Samson DJ, Lefevre F, Aronson N: Wound healing technologies: Low-level laser and vacuum-assisted closure. 2004, Rockville, MD, USA, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), [http://www.ahrq.gov/downloads/pub/evidence/pdf/woundtech/woundtech.pdf]

Costa V, Brophy J, McGregor M: Vacuum-assisted wound closure therapy (V.A.C (R)). 2005, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, McGill University Health Centre (MUHC) Technology Assessment Unit (TAU), 1-24. [http://upload.mcgill.ca/tau/VAC_REPORT_FINAL.pdf]

Pham CT, Middleton PF, Maddern GJ: The safety and efficacy of topical negative pressure in non-healing wounds: a systematic review. J Wound Care. 2006, England, 15: 240-250.

Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee (OHTAC): Negative pressure wound therapy: Update. 2006, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC) Medical Advisory Secretariat (MAS), 1-38. [http://www.health.gov.on.ca/english/providers/program/ohtac/tech/reviews/pdf/rev_npwt_070106.pdf]

Egger M, Zellweger-Zahner T, Schneider M, Junker C, Lengeler C, Antes G: Language bias in randomised controlled trials published in English and German. Lancet. 1997, 350: 326-329.

Moher D, Pham B, Lawson ML, Klassen TP: The inclusion of reports of randomised trials published in languages other than English in systematic reviews. Health Technol Assess. 2003, 7: 1-90.

Galandi D, Schwarzer G, Antes G: The demise of the randomised controlled trial: bibliometric study of the German-language health care literature, 1948 to 2004. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006, 6: 30-

Gotzsche PC, Harden A: Searching for non-randomised studies. 2000, Kopenhagen, Dänemark, The Cochrane Non-Randomised Studies Methods Group (NRSMG) at The Nordic Cochrane Centre, [http://www.cochrane.dk/nrsmg/docs/chap3.pdf]

Britton A, McKee M, Black N, McPherson K, Sanderson C, Bain C: Choosing between randomised and non-randomised studies: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess. 1998, 2: i-124. [http://www.ncchta.org/fullmono/mon213.pdf]

Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, D'Amico R, Sowden AJ, Sakarovitch C, Song F, Petticrew M, Altman DG: Evaluating non-randomised intervention studies. Health Technol Assess. 2003, 7: iii-173.

Reeves BC, van Binsbergen J, van Weel C: Systematic reviews incorporating evidence from nonrandomized study designs: reasons for caution when estimating health effects. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005, 59 Suppl 1: S155-S161.

MacLehose RR, Reeves BC, Harvey IM, Sheldon TA, Russell IT, Black AM: A systematic review of comparisons of effect sizes derived from randomised and non-randomised studies. Health Technol Assess. 2000, 4: 1-154. [http://www.hta.ac.uk/fullmono/mon434.pdf]

Kunz R, Vist G, Oxman AD: The Cochrane Database of Methodology Reviews. Randomisation to protect against selection bias in healthcare trials [online]. 2002, Chichester, UK, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, [http://www.mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clmethrev/articles/MR000012/pdf_fs.html]

Levels of evidence and grades of recommendation. 2001, Oxford, UK, Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM), [http://www.cebm.net/levels_of_evidence.asp]

McCulloch P, Taylor I, Sasako M, Lovett B, Griffin D: Randomised trials in surgery: problems and possible solutions. BMJ. 2002, 324: 1448-1451. [http://bmj.bmjjournals.com/cgi/reprint/324/7351/1448]

Guller U: Surgical outcomes research based on administrative data: inferior or complementary to prospective randomized clinical trials?. World J Surg. 2006, 30: 255-266.

Fraser C, Murray A, Burr J: Identifying observational studies of surgical interventions in MEDLINE and EMBASE. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006, 6: 41-[http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2288/6/41]

Strang WN, Boissel P, Uberla K: Inter-reader variation. The Cochrane Methodology Register. 1997, West Sussex, United Kingdom, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, [http://www.mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clcmr/articles/CMR-660/frame.html]

Bombardier C, Jadad A, Tomlinson G: What is the study design? The Cochrane Methodology Register. 2004, West Sussex, United Kingdom, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, [http://www.mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clcmr/articles/CMR-6639/frame.html]

Thompson R, Bandera E, Burley V, Cade J, Forman D, Freudenheim J, Greenwood D, Jacobs D, Kalliecharan R, Kushi L, McCullough M, Miles L, Moore D, Moreton J, Rastogi T, Wiseman M: Reproducibility of systematic literature reviews on food, nutrition, physical activity and endometrial cancer. Public Health Nutr. 2007, 1-9.

Begg C, Cho M, Eastwood S, Horton R, Moher D, Olkin I, Pitkin R, Rennie D, Schulz KF, Simel D, Stroup DF: Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials. The CONSORT statement. JAMA. 1996, 276: 637-639.

Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman D: The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. JAMA. 2001, 285: 1987-1991. [http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/reprint/285/15/1987]

Des Jarlais DC, Lyles C, Crepaz N: Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: the TREND statement. Am J Public Health. 2004, 94: 361-366. [http://www.trend-statement.org/asp/documents/statements/AJPH_Mar2004_Trendstatement.pdf]

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP: The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007, 147: 573-577. [http://www.annals.org/cgi/reprint/147/8/573.pdf]

Andros G, Armstrong DG, Attinger CE, Boulton AJ, Frykberg RG, Joseph WS, Lavery LA, Morbach S, Niezgoda JA, Toursarkissian B: Consensus statement on negative pressure wound therapy (V.A.C. Therapy) for the management of diabetic foot wounds. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2006, Suppl: 1-32.

Brem H, Sheehan P, Rosenberg HJ, Schneider JS, Boulton AJ: Evidence-based protocol for diabetic foot ulcers. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006, 117: 193S-209S.

Ubbink DT, Westerbos SJ, Evans D, Land L, Vermeulen H: Topical negative pressure for treating chronic wounds. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Edited by: Library TC. 2001, West Sussex, United Kingdom, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, CD001898-10.1002/14651858. [http://www.mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clsysrev/articles/CD001898/pdf_fs.html]1

Fleck T, Gustafsson R, Harding K, Ingemansson R, Lirtzman MD, Meites HL, Moidl R, Price P, Ritchie A, Salazar J, Sjogren J, Song DH, Sumpio BE, Toursarkissian B, Waldenberger F, Wetzel-Roth W: The management of deep sternal wound infections using vacuum assisted closure (V.A.C.) therapy. Int Wound J. 2006, 3: 273-280.

Fisher A, Brady B: Vacuum assisted wound closure therapy. 2003, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, The Canadian Coordinating Office for Health Technology Assessment (CCOHTA), [http://cadth.ca/media/pdf/221_vac_cetap_e.pdf]

Gray M, Peirce B: Is negative pressure wound therapy effective for the management of chronic wounds?. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2004, 31: 101-105.

Inc H: Negative pressure wound therapy for wound healing. 2003, Lansdale, Pennsylvania, USA, Hayes, Inc

Higgins S: The effectiveness of vacuum assisted closure (VAC) in wound healing. 2003, Clayton, Australia, Centre for Clinical Effectiveness (CCE), [http://www.mihsr.monash.org/cce/res/pdf/c/991fr.pdf]

Mayer ED, Boukamp K, Simoes E: Vakuumversiegelung in der Wundbehandlung - Verfahren nach EbM-Kriterien evaluiert? Bewertung aus sozialmedizinischer Sicht. 2002, Lahr (Schwarzwald), Medizinischer Dienst der Krankenkassen (MDK) Baden-Württemberg

Mendonca DA, Papini R, Price PE: Negative-pressure wound therapy: a snapshot of the evidence. Int Wound J. 2006, 3: 261-271.

Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee (OHTAC): Vacuum assisted closure therapy for wound care. 2004, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC) Medical Advisory Secretariat (MAS), 1-59. [http://www.health.gov.on.ca/english/providers/program/ohtac/tech/techlist_2004.html]

Pham C, Middleton P, Maddern G: Vacuum-assisted closure for the management of wounds: an accelerated systematic review. 2003, Adelaide, Australia, Australian safety and efficacy register of new interventional procedures - surgical (ASERNIP-S), [http://www.surgeons.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=ASERNIP_S_Publications&Template=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentFileID=1491]

Shirakawa M, Isseroff RR: Topical negative pressure devices: use for enhancement of healing chronic wounds. Arch Dermatol. 2005, 141: 1449-1453.

Suess JJ, Kim PJ, Steinberg JS: Negative pressure wound therapy: evidence-based treatment for complex diabetic foot wounds. Curr Diab Rep. 2006, 6: 446-450.

Turina M, Cheadle WG: Management of established surgical site infections. Surgical Infections. 2006, 7 (Suppl 3): S33-S41.

Ubbink DT, Vermeulen H, Lubbers MJ: [Local wound care: evidence-based treatments and dressings]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2006, 150: 1165-1172.

Whelan C, Stewart J, Schwartz BF: Mechanics of wound healing and importance of Vacuum Assisted Closure in urology. J Urol. 2005, 173: 1463-1470.

Costa V, Brophy J, McGregor M: Vacuum-assisted wound closure therapy (V.A.C (R)). 2007, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, McGill University Health Centre (MUHC) Technology Assessment Unit (TAU), 1-24. [http://upload.mcgill.ca/tau/VAC_REPORT_FINAL.pdf]

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2288/8/41/prepub

Acknowledgements

All work on this analysis was funded by IQWiG, an independent non-profit and non-government organisation that evaluates the quality and efficiency of health care services in Germany. IQWiG receives its commissions from the Federal Joint Committee (the decision-making body of the self-administration of the German health care services) as well as from the Federal Ministry of Health, and also undertakes projects and research work on its own initiative. All work on this study was supported by IQWiG within the framework of a systematic review on NPWT performed by IQWiG. Three authors (FP, NM, StL) are IQWiG full-time employees; one author (StS) works as an external expert for IQWiG.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

StL and FP initiated the study. FP coordinated the study and conducted the literature search. StL, FP, and StS screened and analysed the retrievals. NM and FP drafted the manuscript. All authors interpreted the data and made an intellectual contribution to the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Peinemann, F., McGauran, N., Sauerland, S. et al. Disagreement in primary study selection between systematic reviews on negative pressure wound therapy. BMC Med Res Methodol 8, 41 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-41

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-41