Abstract

This Mundell-Fleming Lecture focuses on the connections between trade policy and the macroeconomy. Part I considers the evidence on tariffs and growth from an historic vantage point. Part 2 then reviews what we know about trade policy and macroeconomic fluctuations. Although the first part is about growth and the second part is about fluctuations, similar issues and policy implications arise in the two contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Specifically, it may be back due to its revenue-raising potential for a country currently running a current account deficit and needing to reconcile cuts in tax rates with revenue neutrality.

One might say “the elusive Laursen-Metzler effect”, because Obstfeld (1982) showed that theoretical support for the existence of a Laursen-Metzler effect is fragile (in essence, that whether saving rises with an improvement in the terms of trade depends on why the terms of trade improve). In addition, the empirical literature is split, with both Chinn and Prasad (2003) and Agenor and Aizenman (2004) rejecting the hypothesis of such an effect.

Refer, for example, to Mankiw (2014). It is also invoked in discussions of trade negotiations—for example, in the observation that anticipations earlier this year that President Trump would abandon NAFTA were accompanied by immediate depreciation of the Mexican peso against the dollar, which promised to offset any impact of a more restrictive trade policy toward Mexico on the US economy (see for example the discussion in Freund 2017).

As Mundell describes in his own keynote address to the very first IMF Annual Research Conference (Mundell 2001).

Citations are below.

Other work has sought to defend the compatibility of cross-country regressions with the conventional wisdom, arguing that the effects of openness vary with circumstances but are generally positive. See Wacziarg and Welch (2008), Billmeier and Nannicini (2013) and Estevadeordal and Taylor (2013) for research along these lines.

Asking whether higher import duties in the USA are “a good idea” is not exactly the same as asking whether they would stimulate faster growth, but when the University of Chicago’s IGM Forum polled some three dozen economists on this in late 2016, 100% of respondents answered no. http://www.igmchicago.org/surveys/import-duties.

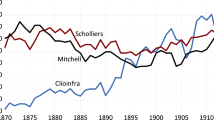

Vamvakidis (2002) finds the same positive correlation for the 1930s.

The regression evidence survives dropping these two countries from the sample, in other words. Not everyone reads the evidence as I do. Irwin (2002) argues that the positive correlation in the O’Rourke sample hinges on the inclusion of key outliers. He adds countries and shows that this weakens the growth–tariff correlation. He does not control for inter alia changes in factor inputs, however, data on such ancillary variables not being readily available for additional countries. Tena-Junguito (2009) similarly considers a larger country sample and reaches Irwin-like conclusions but is similarly unable to directly control for other country characteristics.

There were exceptions, like the German “marriage of iron and rye”, which resulted in both agricultural and industrial imports being taxed, but even there tariffs on agricultural imports were cut starting in the 1890s.

Those additional factors plausibly included transport costs and other frictions segmenting national markets, differences in technological sophistication and different endowments of skilled labor and materials.

The French blockade on imports from Britain was not as effectively enforced in Southern Europe as in Northern Europe, and it is this geographical variation that Jurasz exploits.

I would note, however, that foreign investment in this earlier period was not mainly foreign direct investment; it was mainly portfolio investment (bond finance), so it does not necessarily support the view that foreign finance works best when it is in the form of FDI. Such portfolio investment as occurred could dry up abruptly; there was no dearth of sudden stops and debt crises (Reinhart and Rogoff 2009). If countries that were more dependent on and integrated into global financial markets grew faster, they did so despite their vulnerability to crisis risk.

Countries like Germany, which protected both industry and agriculture, as noted above, were an exception to this generalization about tariffs falling most heavily on manufactured goods. Temin (2002) argues that German growth suffered in this period from the Empire’s maintenance of protection for agriculture, which slowed the shift of resources into industry; to the extent that growth was rapid, it follows that this must have been for other reasons.

Trade policy played a role here as well. Abolition of the Corn Laws (tariffs on agricultural imports) in the 1840s removed protection from a previously favored sector, leading to additional transfer of labor out of agriculture, as producers concentrated on more fertile land, high-value-added crops and more capital-intensive methods. Clark (2002) describes the sources of agricultural productivity growth in this period.

The wage gap between agriculture and manufacturing in the USA was even larger, on the order of fivefold for much of the nineteenth century. But one should be careful. As research at the IMF (Mourmouras and Rangazas 2007) has shown, half of this gap reflects non-wage compensation of farm workers and cost of living differences between urban and rural areas. A portion of the rest reflects that workers in manufacturing worked longer hours. Another portion is due to the measurement problem that some portion of agricultural output is not marketed and therefore unmeasured. Removing these factors yields an estimated labor productivity gap similar to that cited in the text.

Nor is there a positive correlation with tariffs on “exotics” (wine, tea, sugar and other luxury goods, imports of which were taxed exclusively for revenue-raising reasons). Tariffs on agricultural imports, in this sample, are in fact negatively associated with the growth of per capita GDP.

In other words, they may reflect, at least in part, the existence of non-marketed, non-measured output in agriculture, differences in hours worked across sectors, and other factors, as noted in footnote 20.

Describing those positive shocks would require another lecture. A good introduction is the article by Wright (1990) cited earlier.

The argument regarding the nineteenth century must rest mainly on costs of information rather than simple transportation costs, given that the latter could be recouped in a matter of weeks (Rosenbloom 1990).

The special case of the South is the topic of Wright (1986).

The effects of tariff protection would still vary, of course, with the severity of the distortion, which might differ across countries. Unfortunately, there are few systematic cross-country comparisons of labor mobility in this period. For discussion see Long and Ferrie (2005).

These are all industrial inputs into agriculture, which were less important in the nineteenth century.

Completeness requires mentioning a final hypothesis, that tariffs were helpful on big-push grounds in the nineteenth century, when they encouraged countries to invest in a set of complementary industries in each of which productivity depended on investment in the other sectors, but that they were no longer helpful in the twentieth century, when countries could plug into global supply chains, limiting the importance of domestic complementarities. The problem, to my mind, is that the observed change in the tariff-growth relationship long predates the significant development of global supply chains at the end of the century.

See Schwartz (2017) on this constraint.

This was in Keynes’ private evidence to the Macmillan Committee (reprinted in Moggridge 1981).

Equivalently, he described how a tariff, by raising profitability for domestic producers, would encourage investment, boosting output and employment in his proto-Keynesian model. In this emphasis, Keynes was adopting the framework he developed in his Treatise on Money (Keynes 1930), although in the Treatise he did not consider the case for a tariff directly.

Moggridge (1981), p. 120.

See Auerbach (2017a). Where Mundell considered only an import tariff, he was working with a one-good model. With two goods, importables and exportables that are imperfect substitutes, we need the combination of an import tax and export rebate or subsidy in order for offsetting exchange rate changes to leave relative prices unchanged. Baumann et al. (2017) emphasize the importance of the rebate for exporters for this neutrality result. Note that the assumption of zero first-order effects is not to deny the existence of second-order effects due to the move a less distortionary tax system, to which I return momentarily.

While a temporary tariff or border-adjustment tax is different, that’s not what’s under discussion in the tax reform debate. Razin and Svensson (1983) analyze the temporary tariff case in a simple intertemporal model, showing that it will result in less short-run appreciation of the exchange rate than in the permanent tariff case and therefore some short-run improvement in the current account. Erceg et al. (2017) analyze the equivalent policy in a dynamic New Keynesian open economy with optimizing consumers and producers, where producer prices are sticky as in Calvo (1983) and there is full pass-through of exchange rate and tax changes, together with a central bank following a Taylor rule. They show that the Razin-Svensson results carry over, and in addition there will be positive short-run output effects. I note for amusement that these are exactly the effects of a temporary tariff in earlier, less elaborate models with forward-looking behavior such as Eichengreen (1981). There is empirical support for these theoretical propositions: Li (2004) found that exchange rate movements were smaller in episodes of trade liberalization where policy reversals were expected.

Auerbach (2017b) provides further discussion of this scenario, including the possibility that the tax is phased in over time.

This assumes other sources of price stickiness or else asset-valuation effects of the sort described below. Appreciation of the dollar in the final two months of 2016, plausibly reflecting expectations that the newly elected US president would impose new tariffs on imports, was consistent with this interpretation.

It assumes, in the US case, that US imports have sticky foreign currency prices, so they move one-to-one with the exchange rate (passthrough is 100 percent), while the prices of their domestic substitutes are sticky in dollars.

Here, obviously, I am discussing the case of the USA; the more general case is that of domestic currency invoicing or pricing to market.

The pioneering work here was Mundell (1968).

Revenge of the Laursen-Metzler effect, one might say.

Lindé and Pescatori (2017) show that an analogous result holds when international asset markets are complete (when there exists a set of Arrow-Debreu securities contingent on tariffs).

This is the model analyzed in Eichengreen (1981).

Working in a related context, Farhi et al. (2014) show that the standard neutrality result requires a country in this position to partially default on its external debt.

Because a tariff put upward pressure on the CPI, it had a negative real balance effect; hence the contraction. Equivalently, the tariff had to be met by deflation, which increased real balances but reduced output and employment in a model with sticky money wages.

The same issues arise in the case of a border-adjustment tax for a country with a trade deficit (where revenues from imports exceed rebates for exports).

Equivalently, they assumed Ricardian equivalence.

And he implicitly assumed that there was no Ricardian equivalence. Rose and Ostry (1989) adopt analogous assumptions in their benchmark theoretical analysis.

This assumes, once again, that domestic goods are in less than perfectly elastic supply.

In addition, the asset-valuation effects are likely to be even greater than in the base case considered above. But their impact on spending would be at least partially offset by the positive wealth effects of increased productive efficiency and higher investment.

Some argue that the same is likely to be true of the border-adjustment tax in practice, because for example it is hard to apply the rebate to exports of services.

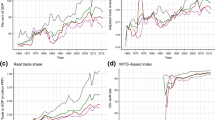

They find the same thing when using lower frequency trade policy data.

This operates through the mechanism emphasized by Melitz (2003), who considered the case of a country that opens up to international trade, where more intense import competition causes less productive firms to exit, allowing only more productive firms to remain.

Which, I like to insist, are really just two ways of saying the same thing, given the formidable challenge for most countries of pegging the exchange rate in an environment of high capital mobility.

There is also the danger of trade wars and retaliation. In theory, the net macroeconomic effects depend on the setting—for example, on whether economies are suffering from liquidity-trap-like conditions (as I showed in Eichengreen 1989). In practice, however, the broader effects are all but certain to be negative, insofar as they make it more difficult for borrowing countries to service and repay their debts and sour the climate for international cooperation.

This view suggests that the advisability of removing or maintaining capital account restrictions is context specific, that their removal should be contingent on, for example, prior steps to strengthen financial markets, institutions, regulation and policy sufficient to ensure that any induced threats to financial stability are limited. It suggests the benefits are likely to exceed the risks only if a country has reached a certain level or threshold of financial and institutional development, in other words. See IMF (2012).

References

Abramovitz, Moses, and Paul David. 1983. Reinterpreting Economic Growth: Parables and Realities. American Economic Association Papers and Proceedings 63: 428–439.

Agenor, Pierre, and Joshua Aizenman. 2004. Saving and the Terms of Trade under Borrowing Constraints. Journal of International Economics 63: 321–340.

Amiti, Mary, and Jozef Konings. 2007. Trade Liberalization, Intermediate Inputs and Productivity: Evidence from Indonesia. American Economic Review 97: 1161–1638.

Aschauer, David. 1987. Some Macroeconomic Effects of Tariff Policy. In Economic Perspectives, 10–18. Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.

Auerbach, Alan. 2017a. Border Adjustment and the Dollar. In AEI Economic Perspectives (February).

Auerbach, Alan. 2017b. Demystifying the Destination-Based Cash-Flow Tax. Paper Presented to the Brookings Panel (7–8 September).

Bairoch, Paul. 1972. Free Trade and European Economic Development in the 19th Century. European Economic Review 3: 211–245.

Bairoch, Paul. 1989. European Trade Policy, 1815–1914. In Cambridge Economic History of Europe, vol. 8, ed. Peter Mathias, and Sidney Pollard, 1–160. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bairoch, Paul. 1993. Economics and World History: Myths and Paradoxes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Barattieri, Alessandro, Matteo Cacciatore, and Fabio Ghironi. 2017. Protectionism and the Business Cycle. Collegio Carlo Alberto, HEC Montreal and University of Washington (July) (unpublished manuscript).

Barbiero, Omar, Emmanuel Farhi, Gita Gopinath, and Oleg Itskhoki. 2017. The Economics of Border Adjustment Tax. Harvard University and Princeton University (June) (unpublished manuscript).

Baumann, Ursel, Alistair Dieppe, and Allan Dizioli. 2017. Why Should the World Care? Analysis, Mechanisms and Spillovers of the Destination Based Border Adjusted Tax. ECB Working Paper no. 2093 (August).

Bhagwati, Jagdish. 1978. Foreign Trade Regimes and Economic Development. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger.

Billmeier, Andres, and Tommaso Nannicini. 2013. Assessing Economic Liberalization Episodes: A Synthetic Control Approach. Review of Economics and Statistics 95: 983–1001.

Bordo, Michael, and Hugh Rockoff. 1996. The Gold Standard as a ‘Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval’. Journal of Economic History 56: 389–428.

Boyer, Russell. 1977. Commercial Policy Under Alternative Exchange Rate Regimes. Canadian Journal of Economics 10: 218–232.

Broadberry, Stephen, and Douglas Irwin. 2006. Labor Productivity in Britain and America During the Nineteenth Century. Explorations in Economic History 43: 257–279.

Calvo, Guillermo A. 1983. Staggered prices in a utility-maximizing framework. Journal of Monetary Economics 12: 383–398.

Chan, Kenneth. 1978. The Employment Effects of Tariffs Under a Free Exchange Rate Regime. Journal of International Economics 8: 415–423.

Chinn, Menzie, and Eswar Prasad. 2003. Medium-Term Determinants of Current Accounts in Industrial and Developing Countries: An Empirical Exploration. Journal of International Economics 59: 47–76.

Clark, Gregroy. 2002. The Agricultural Revolution and the Industrial Revolution: England , 1500–1912. UC Davis (June) (unpublished manuscript).

Collins, William, and Jeffrey Williamson. 2001. Capital Goods Prices, Global Capital Markets and Accumulation: 1870–1950. Journal of Economic History 61: 59–94.

Conybeare, John. 1991. Voting for Protection: An Electoral Model of Tariff Policy. International Organization 45: 57–81.

Dasgupta, Partha, and Joseph Stiglitz. 1988. Learning by Doing, Market Structure, and Industrial and Trade Policies. Oxford Economic Papers 40: 246–268.

Davis, Lance. 1965. The Investment Market, 1870–1914: The Evolution of a National Market. Journal of Economic History 25: 360–365.

Davis, Lance, and Robert Gallman. 2001. Evolving Financial Markets and International Capital Flows: Britain, the Americas and Australia, 1865–1914. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Della Paolera, Gerardo, and Alan Taylor. 2011. A New Economic History of Argentina. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

DeLong, Bradford. 1998. Trade Policy and America’s Standard of Living: A Historical Perspective. In Imports, Exports, and the American Worker, ed. Susan Collins. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution.

DeLong, Bradford, and Lawrence Summers. 1991. Equipment Investment and Economic Growth. Quarterly Journal of Economics 106: 445–502.

Dornbusch, Rudiger. 1987. External Balance Correction: Depreciation or Protection? In Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 249–269.

Eichengreen, Barry. 1981. A Dynamic Model of Tariffs, Output and Employment under Flexible Exchange Rates. Journal of International Economics 11: 341–359.

Eichengreen, Barry. 1989. The Political Economy of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff. Research in Economic History 11: 1–44.

Erceg, Christopher, Andrea Prestipino, and Andrea Raffo. 2017. The Macroeconomic Effects of Trade Policy. Federal Reserve Board (March) (unpublished manuscript).

Estevadeordal, Antoni, and Alan Taylor. 2013. Is the Washington Consensus Dead? Growth, Openness and the Great Liberalization, 1970s–2000s. Review of Economics and Statistics 95: 1669–1690.

Farhi, Emmanuel, Gita Gopinath, and Oleg Itskhoki. 2014. Fiscal Devaluations. Review of Economic Studies 81: 725–760.

Feis, Herbert. 1930. Europe, the World’s Banker, 1870–1914. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Fishlow, Albert. 1985. Lessons from the Past: Capital Markets During the 19th Century and the Interwar Period. International Organization 39: 383–439.

Flandreau, Marc, Jacques Le Cacheux, and Frédéric Zumer. 1998. Stability without a Pact? Lessons from the Gold Standard 1880–1914. Economic Policy 13: 115–162.

Freund, Caroline. 2017. Scrapping NAFTA will Sink the Peso and Expand the Trade Deficit. In Trade & Investment Policy Watch, Washington, DC: Peterson Institute of International Economics (29 August).

Gopinath, Gita. 2017. A Macroeconomic Perspective on Border Taxes. Paper Presented to the Brookings Panel (7–8 September).

Gopinath, Gita, Oleg Itskhoki, and Roberto Rigobon. 2010. Currency Choice and Exchange Rate Passthrough. American Economic Review 100: 304–336.

Hanlon, Walker. 2017. Evolving Comparative Advantage in Shipbuilding During the Transition from Wood to Steel. New York University (unpublished manuscript).

Herrendorf, Berthold, and Todd Schoellman. 2011. Why is Agricultural Productivity so Low in the United States? Arizona State University, Tempe (February) (unpublished manuscript).

International Monetary Fund. 2012. The Liberalization and Management of Capital Flows: An Institutional View (14 November).

Irwin, Douglas. 1998. Did Late 19th Century U.S. Tariffs Promote Infant Industries? Evidence from the Tinplate Industry. NBER Working Paper no. 6835 (December).

Irwin, Douglas. 2002. Interpreting the Tariff-Growth Correlation of the Late 19th Century. American Economic Association Papers and Proceedings 92: 165–169.

Jacks, David. 2006. New Results on the Tariff-Growth Paradox. European Review of Economic History 10: 205–230.

James, John. 1976. The Development of the National Money Market, 1893–1911. Journal of Economic History 35: 878–897.

Juhasz, Reka. 2014. Temporary Protection and Technology Adoption: Evidence from the Napoleonic Blockade. London School of Economics (unpublished manuscript).

Keynes, John Maynard. 1930. A Treatise on Money, vol. 2. London: Macmillan.

Krueger, Anne. 1983. Trade and Employment in Developing Countries: Synthesis and Conclusions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Krueger, Anne. 1984. Trade Policies in Developing Countries. In Handbook of International Economics, vol. 1, ed. Ronald Jones, and Peter Kenen, 519–569. Amsterdam: North Holland.

Krugman, Paul. 1982. The Macroeconomics of Protection with a Floating Exchange Rate. Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy 16: 141–182.

Lagarde, Christine. 2017. Building a More Resilient and Inclusive Global Economy. Brussels (12 April), https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2017/04/07/building-a-more-resilient-and-inclusive-global-economy-a-speech-by-christine-lagarde.

Lehmann, Sibylle, and Kevin O’Rourke. 2011. The Structure of Protection and Growth in the Late Nineteenth Century. Review of Economics and Statistics 93: 606–616.

Li, Xiangming. 2004. Trade Liberalization and Real Exchange Rate Movement. IMF Working Paper no. WP/03/124 (June).

Lindé, Jesper, and Andrea Pescatori. 2017. The Macroeconomic Effects of Trade Tariffs: Revisiting the Lerner Symmetry Result. IMF Working Paper WP/17/151 (July).

Little, Ian, Malcolm David, Tibor Scitovsky, and Maurice Scott. 1970. Industry and Trade in Some Developing Countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Long, Jason, and Joseph Ferrie. 2005. Labor Mobility. In Oxford Encyclopedia of Economic History, vol. 3, ed. Joel Mokyr, 248–250. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mankiw, Gregory. 2014. Principles of Macroeconomics, 7th ed. Independence, KY: South-Western College Publishers.

Melitz, Marc. 2003. The Impact of Trade on Intra-Industry Reallocations and Aggregate Industry Productivity. Econometrica 71: 1695–1725.

Moggridge, Donald, ed. 1981. The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, Volume 20: Activities 1929–1931: Rethinking Employment and Unemployment Policies, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mourmouras, Alex and Peter Rangazas. 2007. Wage Gaps and Development: Lessons from U.S. History. IMF Working Paper no. WP/07/105 (May).

Mundell, Robert. 1961. Flexible Exchange Rates and Employment Policy. Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science 27: 509–517.

Mundell, Robert. 1968. International Economics. New York: Macmillan.

Mundell, Robert. 2001. On the History of the Mundell–Fleming Model. IMF Staff Papers 47: 215–227.

Nielsen, Sopren Bo. 1989. Effects of Macroeconomic Transmission of Tariffs. In Growth and External Debt Management, ed. Hans Singer, and Soumitra Sharma, 211–219. London: Macmillan.

Obstfeld, Maurice. 1982. Aggregate Spending and the Terms of Trade: Is There a Laursen-Metzler Effect? Quarterly Journal of Economics 97: 251–270.

Obstfeld, Maurice. 2016. Tariffs Do More Harm than Good at Home. IMF Blog (8 September), https://blogs.imf.org/2016/09/08/tariffs-do-more-harm-than-good-at-home/.

O’Rourke, Kevin. 2000. Tariffs and Growth in the Late 19th Century. Economic Journal 110: 456–483.

Pahre, Robert. 2007. Politics of Trade Cooperation in the 19th Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pavcnik, Nina. 2002. Trade Liberalization, Exit, and Productivity Improvements: Evidence from Chilean Plants. Review of Economic Studies 69: 245–276.

Razin, Assaf, and Lars Svensson. 1983. Trade Taxes and the Current Account. Economics Letters 13: 55–57.

Reinhart, Carmen, and Kenneth Rogoff. 2009. This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Restuccia, Diego, Dennis Yang, and Xiaodong Zhu. 2008. Agriculture and Aggregate Productivity: A Quantitative Cross-Country Analysis. Journal of Monetary Economics 55: 234–250.

Rodriguez, Francisco, and Dani Rodrik. 2001. Trade Policy and Economic Growth: A Skeptic’s Guide to the Cross-National Evidence. NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2000: 261–338.

Rose, Andrew, and Jonathan Ostry. 1989. Tariffs and the Macroeconomy: Evidence from the USA. International Finance Discussion Paper no. 365. Washington, DC: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (November).

Rosenbloom, Joshua. 1990. One Market or Many? Labor Market Integration in the Late Nineteenth-Century United States. Journal of Economic History 50: 85–107.

Rosenbloom, Joshua. 2002. Looking for Work, Searching for Workers: American Labor Markets during Industrialization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sachs, Jeffrey. 1985. External Debt and Macroeconomic Performance in Latin America and East Asia. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2: 523–564.

Schonhardt-Bailey, Cheryl. 2014. Lessons in Lobbying for Free Trade in 19th-Century Britain: To Concentrate or Not. American Political Science Review 85: 37–58.

Schularick, Moritz, and Thomas Steger. 2010. Financial Integration, Investment and Economic Growth: Evidence from Two Eras of Financial Globalization. Review of Economics and Statistics 92: 756–758.

Schwartz, Nelson. 2017. Workers Needed, But Drug Testing Takes a Toll. New York Times, 25 July, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/24/business/economy/drug-test-labor-hiring.html?ref=business.

Temin, Peter. 2002. The Golden Age of European Growth Reconsidered. European Review of Economic History 4: 3–22.

Tena-Junguito, Antonio. 2009. Bairoch Revisited: Tariff Structure and Growth in the Late Nineteenth Century. European Review of Economic History 14: 111–143.

Tower, Edward. 1973. Commercial Policy Under Fixed and Flexible Exchange Rates. Quarterly Journal of Economics 87: 436–454.

Vamvakidis, Athanasios. 2002. How Robust is the Growth-Openness Connection? Historical Evidence. Journal of Economic Growth 7: 57–80.

Wacziarg, Romain, and Karen Welch. 2008. Trade Liberalization and Growth: New Evidence. World Bank Economic Review 22: 187–231.

Wright, Gavin. 1986. Old South, New South: Revolutions in the Southern Economy Since the Civil War. New York: Basic Books.

Wright, Gavin. 1990. The Origins of American Industrial Success, 1879–1940. American Economic Review 80: 651–668.