Abstract

The crisis has resulted in a substantial rise in unemployment in Europe and a notable divergence in unemployment rates and labour market outcomes post-crisis. In this paper, we offer a detailed examination of the transitional dynamics underpinning changes in employment, unemployment and inactivity across the EU member states during the long period from before the crisis until the recent recovery (2004–2016). We document substantial differences in transitional dynamics across countries and disparate shifts in these over time. We also find systematic cross-country differences in the medium- and long-run trajectories of employment and unemployment generated by these dynamics, which can broadly be associated with differences in labour market institutions and models of labour market regulation and industrial relations (varieties of capitalism or production regimes). Applying a counterfactual analysis, we further document how altering the dynamics of labour market transitions may contribute to reducing significantly the levels of unemployment, and cross-country disparities in these, across the EU.

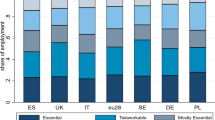

Source: Eurostat data

Source: Authors’ elaboration of Eurostat data

Sources: LFS micro-data and Eurostat aggregate unemployment data. Authors’ computations

Sources: LFS micro-data, authors’ computations

Sources: LFS micro-data, authors’ computations

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Due to missing data on recall questions (past employment status), Germany, the UK and Ireland are excluded from the analysis. Data availability is also limited for some years for some other countries—namely for France, Austria and Spain in 2004–2005; for Sweden in 2004–2006; for Bulgaria and the Netherlands in 2004–2007; and for Malta in 2004–2008.

We identify four such groups: Central Eastern (Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia); Nordics (Netherlands, Finland, Denmark and Sweden); Continental (Belgium, France, Luxemburg and Austria); and Mediterranean (Greece, Spain, Italy, Cyprus, Portugal and Malta). To produce the groups we weight each country on the basis of their GDP. Similar groupings have been used elsewhere in the literature of European labour market dynamics (see, for example, Boeri 2002; Sapir 2006; Ward-Warmedinger and Macchiarelli 2014).

For a recent analysis of transition probabilities using more granular labour market states see Macchiarelli et al. (2018).

This is essentially a transformation matrix, transforming the past distribution of employment outcomes (‘states’) into the current one—or, in matrix notation, Ft=P * Ft−1.

This index is bounded between [0, 1] and can thus be interpreted as a percentage. The inverse of this measure is the well-known Shorrocks and Foster (1987) mobility index, which shows in turn the aggregate probability of individuals changing their labour market status between t and t+ 1, on the basis of matrix P.

In Markov Chain analysis an ergodic distribution is the distribution deriving from multiplying an initial distribution (here, of employment states) Ft by a power n of the transition matrix P such that, for any k > 0, Ft+s=PnFt=Pn+kFt=Ft+s+k. It is thus equivalent to the notion of steady-state. Such a distribution exists if and only if the transition matrix is positive-recurrent, meaning that each and every state can re-occur with a positive probability (i.e., for any state in period t the transition dynamics guarantee that a return to that state will occur in the future, no matter how distant). The ergodic distribution can be calculated by using the left eigenvector that corresponds to the unit (isolated) eigenvalue.

Full results are available from the authors upon request.

Our measure of employment includes successful job-to-job transitions (‘labour market churn’). From results not shown (but available upon request), it appears that the percentage of labour market churn is rather constant both across countries and over time (at around 10%), with few exceptions (e.g., falling in Spain from 15% pre-crisis to 8% post-crisis).

This was accompanied by a substantial decline of transitions from unemployment to inactivity, suggesting perhaps a stronger ‘added worker’ effect in this group.

References

Bentolila, S., and G. Bertola. 1990. Firing costs and labour demand: How bad is eurosclerosis? The Review of Economic Studies 57(3): 381–402.

Boeri, T. 2002. Who’s afraid of the big enlargement? Economic and social implications of the European Union’s prospective eastern expansion (No. 7). Centre for Economic Policy Research.

Boeri, T., and J.F. Jimeno. 2016. Learning from the Great Divergence in unemployment in Europe during the crisis. Labour Economics 41: 32–46.

Boeri, T., and J. Van Ours. 2013. The economics of imperfect labor markets. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Bulligan, G., and E. Viviano. 2017. Has the wage Phillips curve changed in the euro area? IZA Journal of Labor Policy 6(1): 9.

Carcillo, S., R. Fernández, S. Königs, and A. Minea. 2013. NEET youth in the aftermath of the crisis: Challenges and policies, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 164. OECD Publishing.

Cazes, S., S. Verick, and F. Al Hussami. 2011. Diverging trends in unemployment in the United States and Europe: Evidence from Okun’s law and the global financial crisis (No. 994676293402676). International Labour Organization.

Cazes, S., S. Verick, and F. Al Hussami. 2013. Why did unemployment respond so differently to the global financial crisis across countries? Insights from Okun’s law. IZA Journal of Labor Policy 2(1): 10.

Christopoulou, R. and V. Monastiriotis. 2018. Did the crisis make the Greek economy less inefficient? Evidence from the structure and dynamics of sectoral premia. GreeSE Paper No. 125. Hellenic Observatory, LSE.

Daouli, J., M. Demoussis, N. Giannakopoulos, and N. Lampropoulou. 2015. The ins and outs of unemployment in the current Greek economic crisis. South-Eastern Europe Journal of Economics 13(2): 177–196.

Dolado, J.J., M. Jansen, F. Felgueroso, A. Fuentes, and A. Wölfl. 2013. Youth labour market performance in Spain and its determinants: A micro-level perspective, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1039. OECD Publishing.

EC. 2007. Towards common principles of flexicurity: More and better jobs through flexibility and security. Brussels: Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions.

ECB. 2012. Euro area labour markets and the crisis, ECB Occasional Paper No. 138. Task Force for the Monetary policy Committee of the European System of Central Banks, ECB.

Eichhorst, W. and F. Neder. 2014. Youth unemployment in Mediterranean countries, IZA Policy Paper, No. 80.

Elsby, M.W., R. Michaels, and G. Solon. 2009. The ins and outs of cyclical unemployment. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 1(1): 84–110.

Esping-Andersen, G.O. 1990. The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Cambridge: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Grönlund, A., K. Halldén, and C. Magnusson. 2017. A Scandinavian success story? Women’s labour market outcomes in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. Acta Sociologica 60(2): 97–119.

Guichard, S., and E. Rusticelli. 2010. Assessing the impact of the financial crisis on structural unemployment in OECD countries. OECD Economics Department Working Paper No.767, May.

Hall, Peter A., and David Soskice, eds. 2001. Varieties of capitalism: The institutional foundations of comparative advantage. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hijzen, A., L. Monduato, and S. Scarpetta. 2017. The impact of employment protection on temporary employment: Evidence from a regression discontinuity design. Labour Economics 46: 64–76.

Kelly, E., and S. McGuinness. 2015. Impact of the Great Recession on unemployed and NEET individuals’ labour market transitions in Ireland. Economic Systems 39(1): 59–71.

Kilponen, J. and J. Vanhala. 2009. Productivity and job flows: Heterogeneity of new hires and continuing jobs in the business cycle, ECB Working Paper No. 1080. ECB.

Macchiarelli, C., V. Monastiriotis, and N. Lampropoulou. 2018. Transitions in the EU labour market: Structure, crisis and recovery, Report to the DG-EMPL. European Commission.

Marinescu, I. 2017. The general equilibrium impacts of unemployment insurance: Evidence from a large online job board. Journal of Public Economics 150: 14–29.

Marston, S.T., M. Feldstein, and S.H. Hymans. 1976. Employment instability and high unemployment rates. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1976(1): 169–210.

Mauro, J., and S. Mitra. 2015. Understanding out-of-work and out-of-school youth in Europe and Central Asia, World Bank Other Operational Studies 22806. The World Bank.

Monastiriotis, V. 2007. Labour market flexibility in UK regions, 1979–1998. Area 39(3): 310–322.

Monastiriotis, V. 2018. Labour market adjustments during the crisis and the role of flexibility, Social Situation Monitor Research Note (May 2018). Brussels: Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion.

Monfort, P. 2008. Convergence of EU regions: Measures and evolution. Brussels: European Commission, Regional Policy.

Petrongolo, B., and C.A. Pissarides. 2008. The ins and outs of European unemployment. American Economic Review 98(2): 256–262.

Picot, G., and A. Tassinari. 2014. Liberalization, dualization, or recalibration? Labor market reforms under austerity, Italy and Spain 2010–2012. Nuffiled College Working Paper Series in Politics No1741, Oxford University.

Sala, H., J. Silva, and M. Toledo. 2012. Flexibility at the margin and labor market volatility in OECD countries. Scandinavian Journal of Economics 114(3): 991–1017.

Sapir, A. 2006. Globalization and the reform of European social models. Journal of Common Market Studies 44(2): 369–390.

Shorrocks, A.F., and J.E. Foster. 1987. Transfer sensitive inequality measures. The Review of Economic Studies 54(3): 485–497.

Theeuwes, J., M. Kerkhofs, and M. Lindeboom. 1990. Transition intensities in the Dutch labour market 1980–85. Applied Economics 22(8): 1043–1061.

Ward-Warmedinger, M., and C. Macchiarelli. 2014. Transitions in labour market status in EU labour markets. IZA Journal of European Labor Studies 3(1): 17.

Zwick, H.S., S. Syed, and A. Shah. 2016. Augmented Okun’s law within the EMU: Working-time or employment adjustment? A structural equation model. Economics Bulletin 36(1): 440–448.

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion (Grant No. VT/2017/0341).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Monastiriotis, V., Macchiarelli, C. & Lampropoulou, N. Transition Dynamics in European Labour Markets During Crisis and Recovery. Comp Econ Stud 61, 213–234 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41294-019-00084-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41294-019-00084-1