Abstract

The Eurozone crisis has sparked renewed interest in the literature about optimum currency areas, in particular in the role of labor mobility as a mechanism of adjustment to shocks. We study the response of mobility in the Eurozone to national labor market conditions. We measure mobility by using data on stocks of foreign population by nationality. We find that mobility in the Eurozone is relatively low. It responded to national differences in unemployment during the crisis, but neither to national differences in wages nor to national differences in GDP per capita.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Source: AMECO database, European Commission.

The OCA criteria include economic features of countries that lower the probability of asymmetric shocks (diversification of production, trade interdependence, and business cycle synchronization), and mechanisms of adjustment to shocks (price and wage flexibility, factor mobility, and fiscal integration). For a review of the literature, see Dellas and Tavlas (2009).

This effect can be linked to the idea that the fullfilment of OCA criteria is endogenous to monetary integration (Frankel and Rose 1998; Alesina et al. 2002). The idea itself is nonetheless controversial (Krugman 1993; Kalemli-Ozcan et al. 2001). For a critical appraisal of the literature in the light of EMU, see Boltho and Carlin (2013), Wagner (2014), and Aizenman (2018).

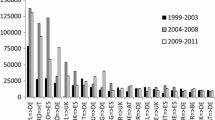

Source: OECD International Migration Database.

In this paper, the terms “mobility” and “migration” are interchangeable. Net inflows of migrants are the difference between inflows of people (the number of immigrants) and outflows of people (the number of emigrants). If net inflows are negative, it means that outflows exceed inflows.

The crude rate of migration is the difference between the total change and the natural change (births minus deaths) of the population. This difference is divided by the average population during the year and expressed per 1000 people.

The net migration rate is the ratio of net inflows of migrants to the average population of the destination country over a given year. It is expressed per 1000 people.

There are 9 out of 28 EU countries that are not members of the Eurozone: Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Sweden, and United Kingdom.

The analysis of how mobility in turn influences labor market adjustments is beyond the scope of this paper (a short review of this subject is made in “Methodology” section).

No data on stocks of foreign population by nationality is available in the case of Cyprus and Malta. It is, therefore, not possible to compute any flows for any year. As for the other countries, the lack of data is such that we could not compute flows before 2011 for Estonia, between 2007 and 2011 for Latvia, and before 2014 for Lithuania. Given the late entry to the Eurozone, the analysis would not have produced any meaningful results if the dataset had contained these countries. In other respects, despite missing data in the case of France, we still could compute net inflows of migrants from other Eurozone countries for at least 7 years (of which 5 years are part of the crisis period).

The Eurostat database includes data from the European Union Labor Force Survey on foreign population by citizenship, age, and labor status, but the definition of country of citizenship is very large (EU-28, EU-15, Total).

A good introduction to the literature about international migration is the handbook edited by Chiswick and Miller (2015). Among studies about labor mobility in Europe, Zaiceva and Zimmermann (2008) explore the historical background and the enlargement of the EU to Central and Eastern European countries. Holland and Paluchowski (2013) examine the context of the recent crisis.

This is currently an unsettled issue because data on skill levels of migrants in the EU is patchy (missing data for some countries) and not available for a period of time sufficiently long to draw some reliable conclusions.

In this matter, Saks and Wozniak (2011) argue that interstate migration in the USA responds to common factors to all locations (national business cycle) rather than local economic conditions.

At the same time, unemployment benefits lower search costs to find a job and may thus not be associated with lower mobility (Tatsiramos 2009).

Pissarides and McMaster (1990) preferred the use of wage growth to wage levels, because they obtained better results from the regression analysis. Eichengreen (1993) found that, for Italy, the wage variable should be in levels and not in first difference. We also did the tests with wage levels and found that conclusions are not affected by the definition of this variable (results are available upon request).

We take into account the changing composition of the Eurozone (from 11 countries in 1999 to 19 countries in 2015).

We use online information which is provided by various Directorates-General in the European Commission.

The eight new member states are Central and Eastern European Countries: Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia, Poland, Slovenia, and Slovakia. There were no restrictions for Cyprus and Malta, given the tiny size of their population.

The software Stata does not supply the R-squared value when one uses the XTLSDVC command (LSDVC estimator). For the reader, we provide it by calculating the correlation between the observed response and the predicted response and then squaring it.

References

Adserà, A., and M. Pytliková. 2015. The role of language in shaping international migration. The Economic Journal 125: F49–F81.

Aizenman, J. 2018. Optimal currency area: A twentieth Century Idea for the twenty-first century? Open Economies Review 29 (2): 373–382.

Akkoyunlu, S., and R. Vickerman. 2001. Migration and the efficiency of european labour markets. In Spatial change and interregional flows in the integrating Europe. Contributions to economics, ed. J. Bröcker, and H. Herrmann. Physica-Verlag HD.

Alesina, A., R. Barro, and S. Tenreyro. 2002. Optimal currency areas. NBER Macroeconomic Annual 17: 301–55.

Arpaia, A., A. Kiss, B. Palvolgyi, and A. Turrini. 2016. Labour mobility and labour market adjustment in the EU. IZA Journal of Migration 5 (21): 1–21.

Beine, M., F. Docquier, and Ç. Özden. 2011. Diasporas. Journal of Development Economics 95: 30–41.

Beine, M., P. Bourgeon, and J.C. Bricongne. 2017. Aggregate fluctuations and international migration. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics.

Bertoli, S., H. Brücker, and J. Fernández-Huertas Moraga. 2013. The European crisis and migration to Germany: Expectations and the diversion of migration flows. IZA discussion paper no. 7170.

Beyer, R., and F. Smets. 2015. Labour market adjustments in Europe and the US: how different? Economic Policy 30 (84): 643–682.

Blanchard, O., and L. Katz. 1992. Regional evolutions. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1: 1–75.

Boltho, A., and W. Carlin. 2013. EMU’s problems: Asymmetric shocks or asymmetric behavior? Comparative Economic Studies 55: 387–403.

Bruno, G.S.F. 2005. Estimation and inference in dynamic unbalanced panel-data models with a small number of individuals. The Stata Journal 87: 361–366.

Chiswick, B., and P. Miller (eds.). 2015. Handbook of the economics of international migration. Amsterdam: Elsevier B.V.

Decressin, J., and A. Fatás. 1995. Regional labor market dynamics in Europe. European Economic Review 39: 1627–55.

De Grauwe, P., and W. Vanhaverbeke. 1993. Is Europe an optimum currency area? Evidence from regional data. In Policy Issues in the Operation of Currency Unions, ed. P. Masson, and M. Taylor, 111–129. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dellas, H., and G. Tavlas. 2009. An optimum-currency-area odyssey. Journal of International Money and Finance 28 (7): 1117–37.

Dao, M., D. Furceri, and P. Loungani. 2014. Regional labor market adjustments in the United States and Europe. IMF working paper no 14/26.

European Central Bank (ECB). 2012. Euro area labour markets and the crisis. Structural issues report, October.

Eichengreen, B. 1990. One money for Europe? Lessons from the US currency union. Economic Policy 10: 117–87.

Eichengreen, B. 1993. Labor markets and European monetary unification. In Policy issues in the operation of currency unions, ed. P. Masson, and M. Taylor, 130–62. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Eichengreen, B. 2014. The Eurozone crisis: the theory of optimum currency areas bites back. Notenstein Academy white paper series.

European Commission. 2011. Labour market developments in Europe 2011. European Economy 2/2011.

European Commission. 2015. Labour market and wage developments in Europe 2015. Report coordinated by Strauss R Arpaia A and Duiella M.

Farhi, E., and I. Werning. 2014. Labor mobility within currency unions. NBER working paper no. 20105.

Frankel, J., and A. Rose. 1998. The endogeneity of the optimum currency area criteria. The Economic Journal 108: 1009–25.

Fratesi, U., and M.R. Riggi. 2007. Does migration reduce regional disparities? The role of skill-selective flows. Review of Urban and Regional Development Studies 19 (1): 78–102.

Gallin, J. 2004. Net migration and state labor market dynamics. Journal of Labor Economics 22 (1): 1–21.

Gibson, H.D., T. Palivos, and G.S. Tavlas. 2014. The crisis in the euro area: An analytic overview. Journal of Macroeconomics 39: 233–39.

Hassler, J., J.V. Rodriguez Mora, K. Storesletten, and F. Zilibotti. 2005. A positive theory of geographic mobility and social insurance. International Economic Review 46 (1): 263–303.

Heinz, F.F., and M. Ward-Warmedinger. 2006. Cross-border labour mobility within an enlarged EU. ECB occasional paper no 52.

Holland, D., T. Fic, A. Rincon-Aznar, L. Stokes, and P. Paluchowski. 2011. Labour mobility within the EU—The impact of enlargement and the functioning of the transitional arrangements. NIESR report.

Holland, D., and P. Paluchowski. 2013. Geographical labour mobility in the context of the crisis. European Employment Observatory Ad-hoc Request.

Jauer, J., T. Liebig, J. Martin, and P. Puhani. 2014. Migration as an adjustment mechanism in the crisis? A comparison of Europe and the United States. OECD social, employment and migration working papers No. 155.

Judson, R.A., and A.L. Owen. 1999. Estimating dynamic panel data models: A guide for macroeconomists. Economics Letters 65: 9–15.

Kalemli-Ozcan, S., B. Sorensen, and O. Yosha. 2001. Economic integration, industrial specialization and the asymmetry of macroeconomic fluctuations. Journal of International Economics 55: 107–37.

Kenen, P. 1969. The theory of optimum currency areas. In Monetary problems of the international economy: An eclectic view, ed. R.A. Mundell, and A.K. Swoboda, 41–60. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Kiviet, J.F. 1995. On bias, inconsistency, and efficiency of various estimators in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics 68: 53–78.

Krugman, P. 1993. Lesson of Massachusetts for EMU. In Adjustment and growth in the European Monetary Union, ed. F. Torres, and F. Giavazzi, 241–61. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Krugman, P. 2012. Revenge of the optimum currency area. NBER Macroeconomics Annual 27: 439–448.

Mundell, R.A. 1961. A theory of optimum currency areas. American Economic Review 51 (4): 657–65.

Pedersen, P., M. Pytlikova, and N. Smith. 2008. Selection and network effects—Migration flows into OECD countries 1990–2000. European Economic Review 52: 1160–86.

Pissarides, C., and I. McMaster. 1990. Regional migration, wage and unemployment: empirical evidence and implications for policy. Oxford Economic Papers 42 (4): 812–31.

Saks, R., and A. Wozniak. 2011. Labor reallocation over the business cycle: New evidence from internal migration. Journal of Labor Economics 29 (4): 697–739.

Tatsiramos, K. 2009. Geographic labour mobility and unemployment insurance in Europe. Journal of Population Economics 22: 267–83.

Wagner, H. 2014. Can we expect convergence through monetary integration? (New) OCA theory versus empirical evidence from European integration. Comparative Economic Studies 56: 176–199.

Zaiceva, A., and K.F. Zimmermann. 2008. Scale, diversity, and determinants of labour migration in Europe. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 24 (3): 267–83.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Alberto Bagnai, Paul Wachtel, the journal’s co-editor, three anonymous referees, Andreea Stoian, Cécile Couharde, Etienne Farvaque, participants at the INFER Conference (Bordeaux, 2017), and participants at the GdRE Conference (Paris, 2017), for useful suggestions. This work is part of a research contract (PACaPe) headed by Xavier Chojnicki (LEM-CNRS, University of Lille), and as such, it has benefited from the financial support of the Directorate General for Foreigners in France (DGEF) of the Ministry of the Interior.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Huart, F., Tchakpalla, M. Labor Market Conditions and Geographic Mobility in the Eurozone. Comp Econ Stud 61, 263–284 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41294-018-0073-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41294-018-0073-5