Abstract

This study was carried out to investigate the relationship between earthworm trophic groups and soil morphology and chemical attributes, and moreover, to determine which of these attributes would be most significant in explaining the distribution of earthworm communities in agro-ecosystems in the Centre-West region of Côte d’Ivoire. Earthworms' soil morphology and soil samples were studied in three agro-ecosystems: 20-year-old cocoa plantations, 5-year-old mixed cocoa plantations and mixed crop-fields. The semi-deciduous forests near the agro-ecosystems were also sampled and considered as control plots. Earthworm global densities varied on average between 53.9 ± 7.9 and 86.0 ± 19.0 individuals m−2 and biomass between 16.5 ± 3.1 and 20.6 ± 4.1 g m−2 under these ecosystems. Path analysis produced a significant model: soil morphology and chemical attributes under different agro-ecosystems affected the density and biomass of earthworm trophic groups, and these attributes are potential regulators of the fauna communities. The morphological components related to dead leaves (r2 = 0.73, P < 0.05) and fine woods quantities (r2 = 0.71, P < 0.05) are most decisive for detritivore abundances, whereas geophageous mesohumic abundances were positively affected by soil organic carbon (r2 = 0.79, P < 0.05) and N (r2 = 0.84, P < 0.05) and geophageous polyhumic abundances were positively affected only by soil N (r2 = 0.63, P < 0.05). In agro-ecosystems the relationship between soil conditions and earthworm communities varied between earthworm trophic groups, so detritivores were more affected by litter quantity, whereas shallow geophageous populations were guided by soil organic matter.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Earthworms represent an important soil faunal group commonly named soil ecosystem engineers (sensu Jones et al. 1994) that affect soil fertility and conservation through burrowing, ingesting and egesting soil as cast (Lavelle et al. 2006; Blouin et al. 2013; Kanianska et al. 2016). Moreover, earthworms are assumed to play the key ecological roles in litter comminution and soil organic matter decomposition processes which are conditioned by the functional traits of different species (Bouché 1977; Dewi and Senge 2015). They were mainly classified into trophic categories of detritivores and geophageous based on their feeding and living preferences (Lee 1985). Detritivores live and feed at the soil surface on plant litters; their burrowing activity is low when an adequate food source is available. Geophageous feed deeper in the soil organic matter and dead fine roots mixed with soil (Lavelle 1981). According to the feeding strategies in relation to soil organic matter amounts ingested, geophageous may be subdivided into three groups such as polyhumics, mesohumics and oligohumics. Polyhumics consume considerable amount of organic matter, while mesohumics and oligohumics feed on soil, respectively, fairly and poor in organic matter (Lavelle 1981).

Earthworm’s abundance is affected by resource availability as well as disturbances (Jouquet et al. 2018). Agricultural practices induced disturbances that affect the size and composition of the earthworm communities by impacting their ecological groups (Smith et al. 2008; Spurgeon et al. 2016). However, the knowledge about effects of soil environmental variability in shaping earthworm assemblages is poorly understood (Ettema and Wardle 2002). In tropical soils, studies have documented the effects of different land use practices on earthworm communities (Koné et al. 2012; Tondoh et al. 2015). Tondoh et al. (2015) reported a reduction in detritivore species populations, namely Millsonia lamtoiana (Omodeo and Vaillaud 1967), Dichogaster baeri (Sciacchitano 1952) and Dichogaster erhrhardti (Michaelsen 1898) with forest conversion into cocoa plantations, while Koné et al. (2012) showed increases in both detritivore Dichogaster baeri (Sciacchitano 1952) and D. saliens (Beddard 1893) abundance with the adoption of legume-based fallows. Remarkably little is known about earthworm feeding ecology and their relationship to soil morphology and chemical quality in agro-ecosystems. Moço et al. (2010) reported that organic matter, soil acidity and litter quality were regulators of the soil fauna functional groups under cacao agroforestry systems, but litter quality was more decisive than soil quality. Also, Koné et al. (2012) reported a positive influence of soil organic matter on the populations of mesohumic worm M. omodeoi (Sims 1986) under Chromoleana odorata (L.) King and Robinson fallow, whereas litter feeders and polyhumic populations decreased.

In the same study area, investigations carried out by Guéi and Tondoh (2012) revealed that earthworm assemblage is guided by soil organic matter content, which is subject to the type of land use. Continuous conversions of forests into agricultural lands are likely to be a major source of threat to population conservation. However, the better understanding of the soil property impacts on earthworm trophic groups in agro-ecosystems may be required to better manage these organism communities and lead to more sustainable soil management strategies. This paper dealt with the current state of knowledge and aimed to determine the relationship between earthworm trophic groups and soil physical and chemical characteristics in contrasted agro-ecosystems as opposed to the semi-deciduous forests. We hypothesized that earthworm feeding assemblages are controlled by edaphic conditions, mainly soil organic matter.

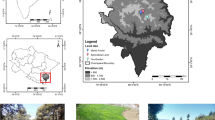

Study sites

We conducted the study around the village Goulikao in the Centre-West region of Côte d’Ivoire (6°30′N, 5°31′W). In the 1970s, this area was part of the main cocoa production area characterized by a high rate of deforestation. As a result, the landscape is composed of a mosaic of land-uses including forests, cocoa plantations, fallows and food crops spread around three settlements, namely Petit Bouaké (6°31.4′ N, 5°31.6′ W), Djè Koffikro (6°28.8′ N, 5°30.4′ W) and N’Kroiêdjô (6°30.9′ N, 5°30.2′ W) located each at least 2 km from the main village Goulikao. These settlements are exclusively occupied by farmers from the savanna areas of the country seeking arable lands for cocoa farming. The land-use system consisted in a mixture of perennial and food crops with fallow as intermediary step for soil regeneration in slash and burn agricultural systems. Food crops such as plantains (Musa spp.) are mixed with cocoa trees until 5-year-old with the aim of having ultimately a cocoa plantation.

The climate is a subequatorial type divided into four seasons. The long dry season starts from November to February, the long wet season from March to June, the short dry season from July to August and the short wet season from September to October. The annual mean rainfall is about 1626.7 mm with an average relative humidity of 79%. The average monthly temperature was about 26 °C with low monthly variability of 1.6 °C. Soils are ferralsols (World Soil Reference 2006), slightly acid in the top 20 cm (pH < 6.5) with a sandy-loam texture (Assié et al. 2008). Nutrient contents are low and decrease rapidly from the upper soil layer to 20 cm depth.

Methods

Sampling and extraction of earthworms’ soil morphology

The sampling campaign took place from June to July 2008 during the major rainy season along a gradient of land-use types starting from forest (baseline plot) to food crops referred to as the most disturbed ecosystem. Specifically, four land-use types including semi-deciduous forests (SF), 20-year-old cocoa plantations (OCP), 5-year-old mixed cocoa plantations (MCP) and mixed crop fields (MCF) were selected in each locality (Petit Bouaké, Djè Koffikro and N’Kroiêdjô) of the landscape in order to obtain 15 replicates for each at the scale of the study area. The mixed-crop fields consisted of a mixture of annual and perennial food crops, such as: cassava, yam, plantains (Musa spp.), maize and vegetables.

We sampled earthworms using a modified method recommended for tropical soils (Anderson and Ingram 1993). It consists at each sampling point in excavating three soil monoliths (50 × 50 × 30 cm) spaced by 5 m interval along a transect (Guéi and Tondoh 2012). Earthworms, hand-sorted and preserved in 4% formaldehyde solution, were identified to species level (Tondoh and Lavelle 2005; Csuzdi and Tondoh 2007), counted and weighted. In this study, we assigned species into four trophic groups (Lavelle 1981) including detritivores and geophageous polyhumics, mesohumics and oligohumics (Table 1).

Soil and litter sampling for study of morphology and chemical properties

Soil morphology is an assessment of the contribution of soil aggregates of different sizes and origins (physical or biogenic), plants, gravels and stones and other components to the spatial architecture of the upper centimetres of soil and derived from visual separation of these items (Topoliantz et al. 2000). Near each soil monolith, a cube of soil, 10 × 10 cm down to 10 cm depth was taken. Soil physical or biogenic aggregates were gently separated as well as other remaining materials such as dead leaves and shoot debris, seeds, gravels and woody debris (Velasquez et al. 2007). The biogenic aggregates (casts, galleries, nests) mainly produced by earthworms, termites, ants and coleoptera were regrouped into three size classes: small biogenic aggregates (BA(1) ≤ 1 cm), medium biogenic aggregates (1 cm ≤ BA(2) ≤ 3 cm) and large biogenic aggregates (BA(3) ≥ 3 cm). Soil physical aggregates produced by chemical–physical processes were also distributed among small, medium and large classes as the biogenic aggregates. Separation was done by gently breaking the soil apart among its natural constituents. Depending on the soil and training of the operator, it took 1–3 h to process one sample. Separated items were counted and the total quantity was given in item numbers by square metre.

At each sampling point, nine soil cores (Ø = 5 cm) were randomly collected at 0–10 cm, air-dried, sieved and mixed thoroughly to form a composite sample. The soil samples were analysed for soil organic carbon (SOC), total N, available P and pH determination. SOC and total N were assessed by dry combustion in a CHN (Thermo-Electron NA-1500). Available P was extracted according the Olsen–Dabin method and was determined by colorimetry at 660 nm (Murphy and Riley 1962). Soil pH was measured in a soil:water suspension at a 1:1 ratio.

Statistical analysis

A total of 15 replicates were considered as the distance separating the three soil monoliths at each sampling point was not enough to consider them as true replicates, meaning that variables were averaged to form a single replicate. The impact of land-use change on earthworm density and biomass, and soil variables was examined using a one-way ANOVA with the Fisher’s LSD test for multiple mean comparisons. The statistical tests were conducted using STATISTICA 7.0 (Statsoft, Tulsa, USA).

The multivariate co-inertia analysis was used to identify relationships between earthworm distributions and environmental variables. Earthworm feeding groups (abundances) were used as ‘ecological groups’ and soil morphology (biogenic and physical aggregates, leaves, shoot and woody debris, seeds, gravels) and chemical attributes (C, N, C/N, pH and available P) as ‘environmental variables’. The statistical significance of the co-inertia was evaluated with a Monte Carlo test with 1000 permutations. We performed the analyses with the software ADE-4 (Thioulouse et al. 1997) available at http://pblil.univ-lyon1.fr/ADE-4/. Additionally to the co-inertia analysis, the interest was to evaluate how environmental variables may influence the distribution of earthworm feeding groups. Thus, one decided to use path analysis to observe causal relations between soil morpho-chemical properties and earthworm community density and biomass. Path coefficient analysis was performed by the lavaan package with R sofware (Rosseel 2012) available at https://github.com/yrosseel/lavaan/issues.

Results

Soil morpho-chemical properties

The conversion of semi-deciduous forests into agro-ecosystems induced a decrease in medium biogenic aggregates (F = 0.75, P = 0.016), leaves (F = 13.6, P < 0.001), woods (F = 9.14, P < 0.001) and stones (F = 3.47, P = 0.02) on the contrary to roots (F = 35.2, P < 0.001), small (F = 18.1, P < 0.001) and medium (F = 19.64, P < 0.001) soil physical aggregates which increased in cocoa plantations. Mixed crop-fields yielded the highest seed quantity (F = 17.07, P < 0.001) (Table 2).

Forest conversion into agro-ecosystems induced significant changes in SOC (F = 16.62, P < 0.001) and total N (F = 13.38, P < 0.001) contents. The highest SOC and N values were displayed under forests and represented twice more the values found under mixed-crop fields (Table 2). In contrast, C/N ratios did not show significant variations between the land-use types. Soil pH values were highest in agro-ecosystems (F = 4.51, P = 0.007), particularly in mixed cocoa plantations of 5-year-old (6.87 ± 0.19) and mixed-crop fields (6.69 ± 0.17). Available phosphorus was lowest in 20-year-old cocoa plantations (41.07 ± 4.93 mg kg−1) and highest in 5-year-old mixed cocoa plantations (58.6 ± 4.42 mg kg−1) (F = 3.56, P = 0.02) (Table 2).

Earthworm communities in different land-use systems

Earthworm total densities varied on average between 53.9 ± 7.9 and 86.0 ± 19.0 individuals m−2 and biomass between 16.5 ± 3.1 and 20.6 ± 4.1 g m−2 under various ecosystems evaluated (Table 3). Total earthworm density was not significantly different among the land-use types; however, detritivore (F = 8.16, P < 0.001) and geophageous mesohumic (F = 3.1, P = 0.045) densities, and geophageous polyhumic biomass (F = 5.6, P = 0.002) decreased in agro-systems. Geophageous polyhumics (42%) and detritivores (39%) were the most abundant taxa; geophageous oligohumics were the less abundant groups and their density was about 1% of the total earthworm density. With respect to the biomass, geophageous mesohumics (52%) and detritivores (33%) were the dominant groups, whereas geophageous oligohumics which accounted for 1% of the total biomass were the least abundant (Table 3).

Co-inertia analysis of fauna communities and soil morphology and chemical attributes

The results of co-inertia analysis of earthworm feeding groups and soil morphology and chemical attributes showed significant relationships (RV coefficient: 0.85, P < 0.008 and RV coefficient: 0.90, P < 0.001 for soil morphology and chemical attributes, respectively) (Figs. 1, 2). The first factor accounted for twice more of the total variability in each co-inertia analysis indicating that it revealed all information. The first factor (61.7%) of co-inertia analysis between earthworms and morphology associated geophageous polyhumics biomass with seed, geophageous mesohumic density and biomass with roots and large biogenic aggregates, and detritivore populations with leaves and wood debris. Cocoa plantations and semi-deciduous forests, respectively, exhibited this pattern most strongly (Fig. 1). As far as the second co-inertia analysis (earthworms-chemical variables) is concerned, factor 1 (76.3%) dealt with associations on the one hand between geophageous polyhumics, SOC and C/N ratios, and on the other hand detritivore biomass and soil pH (Fig. 2).

Co-inertia analysis combining soil morphology and earthworm trophic groups. SF semi-deciduous forests, OCP 20-year-old cocoa plantations, MCP 5-year-old mixed cocoa plantations, MCF mixed crop-fields, Detri. d detrivore density, Geo. meso. d geophageous mesohumic density, Geo. poly. d geophageous polyhumic density, Geo. oligo. d geophageous oligohumic density, Detri. b detrivore biomass, Geo. meso. b geophageous mesohumic biomass, Geo. poly. b geophageous polyhumic biomass, Geo. oligo. b geophageous oligohumic biomass, BA biogenic aggregates, PA soil physical aggregates, (1) small ≤ 1 cm, (2) 1 cm ≤ medium ≤ 3 cm, (3) large ≥ 3 cm

Co-inertia analysis combining soil chemical properties and earthworm trophic groups. SF semi-deciduous forests, OCP 20-year-old cocoa plantations, MCP 5-year-old mixed cocoa plantations, MCF mixed crop-fields, Detri. d detrivore density, Geo. meso. d geophageous mesohumic density, Geo. poly. d geophageous polyhumic density, Geo. oligo. d geophageous oligohumic density, Detri. b detrivore biomass, Geo. meso. b geophageous mesohumic biomass, Geo. poly. b geophageous polyhumic biomass, Geo. oligo. b geophageous oligohumic biomass

Soil morpho-chemical properties and earthworm communities: path analysis

Path analyses with soil morphology and chemical properties as exogenous variables and earthworm trophic group attributes as endogenous variables, showed a significant path relating soil morphology variables and the detritivore densities (T = 1.89, P < 0.01), and only a significant relationship (P < 0.05) between chemical parameters and geophageous mesohumic and polyhumic populations (Fig. 3). The oligohumic worm density and biomass were not influenced by soil attributes (Fig. 3d).

Path model relating earthworm trophic group attributes as endogenous variables (A-detritivore; B-geophageous mesohumic; C-geophageous polyhumic; D-geophageous oligohumic), and soil morphology and chemical properties as exogenous variables. BA biogenic aggregates, PA soil physical aggregates, (1) small ≤ 1 cm, (2) 1 cm ≤ medium ≤ 3 cm, (3) large ≥ 3 cm. PC path coefficient, significant at P < 0.05. P values in brackets

Detritivores were positively affected by soil morphology. According to path coefficient analysis, leaves (r2 = 0.73, P < 0.05) and fine woods (r2 = 0.71, P < 0.05) were the morphology attributes with a strong positive effect on the density and biomass of detritivores. However, they did not show significant relationship with soil chemical parameters (T = 0.11, P = 0.71). As for geophageous mesohumic worms, they were positively affected by soil chemical status (Fig. 3b) as shown by their positive relationship with SOC (r2 = 0.79, P < 0.05) and N (r2 = 0.84, P < 0.05) indicating the overwhelming influence of chemical attributes. Similarly, the density and biomass of geophageous polyhumics were positively affected only by soil N (r2 = 0.63, P < 0.05) (Fig. 3c).

Discussion

The co-inertia analyses showed significant relationships between earthworm trophic groups and soil morphology and chemical attributes, indicating that forests’ conversion into agro-ecosystems associated with soil attributes changes affected earthworm communities. These observations are consistent with previous results yielded by Singh et al. (2016) in the agro-ecosystems of the northwestern part of the Punjab, India. Some feeding groups are more sensitive than others to the effect of forests’ conversion into agro-ecosystems. Agricultural practises particularly affected detritivore, geophageous polyhumic and mesohumic densities while oligohumic populations were not influenced. These results highlight the idea that soil heterogeneity induced by land use practices contributed to the formation of population patches for some earthworm species (Jiménez et al. 2011). For instance, in soils with a direct seeded system with living mulch, epigeic earthworm populations were more abundant than those in conventional farming systems with ploughing (Pelosi et al. 2009). As detritivore earthworms feed on plant litters at the soil surface (Lee 1985), they are negatively impacted by decreasing in litter cover and ploughing as they cannot gain access to their trophic resource (Jiménez et al. 2011; Bertrand et al. 2015). This assertion is corroborated by the path analysis that showed a positive control of dead leaves and fine woods over the abundance of detritivore worms. Moreover, detritivore earthworms are positively influenced by the availability of food and moist soil conditions, and such conditions are provided by soil cover by litter and dead fine woods (Bertrand et al. 2015). Earthworms like moist soils and are most active in such conditions because the water protection mechanisms in their bodies are not well developed. Their body functioning such as respiration rate strongly depends on the gas diffusion through the moist body wall (Lapied et al. 2009).

Endogeic earthworms, i.e., geophageous polyhumics and mesohumics were affected by soil organic matter content mostly by soil organic carbon and total N that affected directly and positively their density. These results are consistent with previous observations in tropical (Guéi and Tondoh 2012; Huerta and Van der Wal 2012; Moço et al. 2010) and temperate agro-ecosystems (Schirrmann et al. 2016), which suggested that soil organic matter are strong drivers of the abundance of endogeic earthworm communities in agricultural ecosystems. Endogeic earthworm populations were guided by soil organic matter content. They rapidly responded to changes in C availability induced by soil management practices (Lapied et al. 2009), and this is one of the main reasons why they are considered as good bio-indicators of changes in soil quality induced by land use change (Guéi and Tondoh 2012).

This work also indicates that geophageous oligohumics were only the endogeic earthworm groups that were not affected by land use type and soil attributes. This is corroborated by the co-inertia result that showed no association between polyhumic earthworm populations and soil chemical and morphological properties. These observations tend to confirm that species of these trophic groups withstood adverse effects of forest conversion to agro-ecosystems as they lived deeper in soil and consumed soil less rich in organic matter (Bouché 1977; Lavelle 1981). The soil depth conditions offered protection against agricultural detrimental practices such as tillage, mineral fertilizers and herbicide applications. For instance, Fraser et al. (1996) observed in temperate soils that the endogeic earthworm Apporrectodea caliginosa dominates and is more tolerant to agricultural soils because it lived in relatively protected habitat within the soil.

Conclusions

Our studies demonstrated that the relationship between soil conditions and earthworm communities varied between earthworm functional groups in agro-ecosystems. The detritivore populations were more affected by litter quantity than shallow geophageous groups that were mainly guided by soil organic matter. Soil morphology components related to dead leaves and fine woods are the most decisive attributes for detritivore earthworm density. Chemical attributes which affected geophageous polyhumics and mesohumics in cocoa systems and mixed crop-fields included mainly soil organic carbon and nitrogen. Because earthworms are important as soil ecosystem engineers (sensu Jones et al. 1994), maintaining litter cover at soil surface could be a good practice to promote their healthy activities to improve ecosystem functioning in tropical agro-ecosystems.

References

Anderson JM, Ingram J (1993) Tropical soil biology and fertility: a handbook of methods. CABI, Oxford, p 171

Assié KH, Angui KTP, Tamia AJ (2008) Effet de la mise en culture et des contraintes naturelles sur quelques propriétés physiques ferrallitiques au Centre-Ouest de la Côte d’Ivoire: conséquences sur la dégradation des sols. Eur J Sci Res 23:149–166

Beddard FE (1893) On some new species of earthworms from various parts of the world. Proc Zool Soc Lond 1892:666–706

Bertrand M, Barot S, Blouin M, Whalen J, de Oliveira T, Roger-Estrade J (2015) Earthworm services for cropping systems. A review. Agron Sustain Dev 35:553–567

Blouin M, Hodson ME, Delgado EA, Baker G, Brussaard L, Butt KR, Dai J, Dendooven L, Pérès G, Tondoh JE, Cluzeau D, Brun JJ (2013) A review of earthworm impact on soil function and ecosystem services. Eur J Soil Sci 64:161–182

Bouché MB (1977) Stratégies lombriciennes. In: Lohm U, Persson T (eds) Soil organism as components of ecosystems. Ecology Bulletin. eds, pp 122–132

Csuzdi C, Tondoh EJ (2007) New and little-known earthworm species from the Ivory Coast (Oligochaeta: acanthodrilidae: Benhamiinia-Eudrilidae). J Nat Hist 41:2551–2567

Dewi WS, Senge M (2015) Earthworm diversity and ecosystem services under threat. Rev Agric Sci 3:25–35

Ettema CH, Wardle DA (2002) Spatial soil ecology. Trends Ecol Evol 17:177–183

Fraser PM, Williams PH, Haynes RJ (1996) Earthworm species, population size and biomass under different cropping systems across the Canterbury Plains, New Zealand. Appl Soil Ecol 3:49–57

Guéi AM, Tondoh EJ (2012) Ecological preferences of earthworms for land-use types in semi-deciduous forest area, Ivory Coast. Ecol Indic 18:644–651

Huerta E, Van der Wal H (2012) Soil macroinvertebrates’ abundance and diversity in home gardens in Tabasco, Mexico, vary with soil texture, organic matter and vegetation cover. Eur J Soil Biol 50:68–75

Jiménez JJ, Decaëns T, Amézqita E, Rao I, Thomas RJ, Lavelle P (2011) Short-range spatial variability of soil physico-chemical variables related to earthworm clustering in a neotropical gallery forest. Soil Biol Biochem 43:1071–1080

Jones CG, Lawton JH, Shachak M (1994) Organisms as ecosystem engineers. Oikos 69:373–386

Jouquet P, Chaudhary E, Kumar ARV (2018) Sustainable use of termite activity in agro-ecosystems with reference to earthworms. A review. Agron Sustain Dev 38:3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-017-0483-1

Kanianska R, Jauová J, Makovníková J, Kizeková M (2016) Assessment of relationships between earthworms and soil abiotic and biotic factors as a tool in sustainable agricultural. Sustainability 8:906. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8090906

Koné AW, Edoukou EF, Tondoh JE, Gonnety JT, Angui KT, Masse D (2012) Comparative study of earthworm communities, microbial biomass, and plant nutrient availability under 1-year Cajanus cajan (L.) Millsp and Lablab purpureus (L.) Sweet cultivations versus natural regrowths in a guinea savanna zone. Biol Fertil Soils 48:337–347

Lapied E, Nahamani J, Rousseau JX (2009) Influence of texture and amendments on soil properties and earthworm communities. Appl Soil Ecol 43:241–249

Lavelle P (1981) Stratégies de reproduction chez les vers de terre. Acta Oecol 2:117–133

Lavelle P, Decaëns T, Aubert M, Barot S, Blouin M, Bureau F, Margerie P, Mora P, Rossi JP (2006) Soil invertebrates and ecosystem services. Eur J Soil Biol 42:3–15

Lee KE (1985) Earthworms: their ecology and relationships with soils and land use. Academic Press, Sydney

Michaelsen W (1898) Über eine neue Gattung und vier neue Arten der Unterfamilie Benhamini. Mitteilungen Naturhistorischen Museum Hamburg 15:165–178

Moço SKM, Gama-Rodrigues FE, Gama-Rodrigues CA, Machado RCR, Baligar CV (2010) Relationships between invertebrate communities, litter quality and soil attributes under different cacao agroforestry systems in the south of Bahia, Brazil. Appl Soil Ecol 46:347–354

Murphy J, Riley JP (1962) A modified single solution method for the determination of phosphate in natural waters. Anal Chim Acta 27:31–36

Omodeo P, Vaillaud M (1967) Les Oligochètes de la savane de Gpakobo en Côte d’Ivoire. Bull Inst Français Afrique. Noire 29:925–944

Pelosi C, Bertrand M, Roger-Estrade J (2009) Earthworm community in conventional, organic and direct seeding with living mulch cropping systems. Agron Sustain Dev 29:287–295

Rosseel Y (2012) Lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling and more Version 0.5-12 (BETA). https://github.com/yrosseel/lavaan/issues

Schirrmann M, Joschko M, Gebbers R, Kramer E, Zörner M, Barkusky D, Timmer J (2016) Proximal soil sensing—a contribution for species habitat distribution modelling of earthworms in agricultural soils? PLoS ONE 11:e0158271. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158271

Sciacchitano I (1952) Oligochètes de la Côte d’Ivoire. Revue Suisse Zoology 59:447–486

Sims RW (1986) Revision of the Western African earthworm genus Millsonia (Octochaetidae, Oligochaeta). Bull Br Mus Nat Hist Zool 50:273–313

Singh S, Singh J, Vig AP (2016) Effect of abiotic factors on the distribution of earthworms in different land use pattern. J Basic Appl Zool 74:41–50

Smith RG, Mc Swiney CP, Grandy AS, Suwanwaree P, Snider RM, Robertson GP (2008) Diversity and abundance of earthworms across an agricultural land-use intensity gradient. Soil Tillage Res 100:83–88

Spurgeon DJ, Liebeke M, Anderson C, Kille P, Lawlor A, Bundy JG, Lahive E (2016) Ecological drivers influence the distributions of two cryptic lineages in an earthworm morphospecies. Appl Soil Ecol 108:8–15

Stephenson J (1928) Oligocheata from lake tanganyiga (Dr. C. Christy's Expedition 1926). Ann Mag Nat Hist 10:1–17

Thioulouse J, Chessel D, Dolédec S, Olivier JM (1997) ADE-4: a multivariate analysis and graphical display software. Stat Comput 7:75–83

Tondoh EJ, Lavelle P (2005) Population dynamics of Hyperiodrilus africanus (Oligochaeta, Eudrilidae) in Ivory Coast. J Trop Ecol 21:493–500

Tondoh JE, Kouamé FN, Guéi AM, Sey B, Koné AW, Gnessougou N (2015) Ecological changes induced by full-sun cocoa farming in Côte d’Ivoire. Glob Ecol Conserv 3:575–595

Topoliantz S, Ponge JF, Viaux P (2000) Earthworm and enchytraeid activity under different arable farming systems, as exemplified by biogenic structures. Plant Soil 225:39–51

Velasquez E, Pelosi C, Brunet D, Grimaldi M, Martin M, Rendeiro AC, Barrios E, Lavelle P (2007) This ped is my ped: visual separation and near infrared spectra allow determination of the origins of soil macroaggregates. Pedobiologia 51:75–87

World Soil Base for Soil Resource (2006) World soil resources reports, 103. A framework for international classification, correlation and communication. FAO, p 127

Acknowledgements

This work was part of the Ph.D dissertation at the “Université Nangui Abrogoua” of the first author, who is grateful for the financial support of UNEP-GEF through the project N° GF/2715-2 “Conservation and Sustainable management of Below-Ground Biodiversity (CSM-BGBD). We thank farmers and technicians for helping us to achieve the outputs of the project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Guéi, A.M., N’Dri, J.K., Zro, F.G.B. et al. Relationships between soil morpho-chemical parameters and earthworm community attributes in tropical agro-ecosystems in the Centre-West region of Côte d’Ivoire, Africa. Trop Ecol 60, 209–218 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42965-019-00021-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42965-019-00021-4