Abstract

In this study, the ignition characteristics and the flow properties of the mixed convection flow are presented. Detailed formulations of the forced, natural and mixed convection problems have been discussed. In order to avoid inconvenient switch between the forced and natural convection we introduce a continuous transformation in the mixed convection. We make a comparison between these situations which reveal a good agreement. For mixed convection flow, the ignition distance is explicitly expressed as a function of the Prandtl number, reaction parameter and wall temperature. It has been observed that owing to the increase of the aforesaid parameters, the thermal ignition distance is reduced. Numerical results are illustrated for velocity, temperature, and concentration for different physical parameters. Furthermore, the development of combustion is presented by using streamlines, isotherms and isolines of fuel and oxidizer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Reactive boundary layer flow has received extensive attention in the case of ignition combustion because the research on this subject is not only related to the basic problem of combustion theory but also related to the practical problems such as flame stabilization in combustor [5], the development of industrial combustor [4], fires external to storage or processing equipment [7], the process of initiation of accidental fires and explosion [5] etc. Furthermore, the ignition phenomenon is important from an academic perspective.

Toong [1] investigated the ignition conditions in the flow of the laminar boundary layer on a hot flat plate under forced convection. The approximate solution to the boundary layer equations obtained by the series expansion method. The similarity between experimental data and the numerical results was qualitatively satisfactory.

The development of combustion was depicted to reveal variations in velocity, temperature, reaction rate and concentration. Sheu and Lin [2] carried out the ignition phenomenon for non-catalytic flow over a wedge shaped plate under forced convection. The apparent ignition criterion was defined according to the relevant Damköhler number, which strongly influenced by several system parameters.

Law [3] investigated stagnation point flow of an isothermal hot surface. If the wall temperature exceeds the critical value determined by the relevant system parameters, the gas phase combustion occurs on the whole wall. This critical wall temperature was considered to be the lowest ignition temperature of the wall. Sheu and Lin [4] studied the combustion of a non-premixed boundary layer flow through a wedge shaped porous plate under the effects of forced convection. Theoretical ignition phenomena were derived from large activation energy asymptotic methods. In addition, asymptomatic and numerical results were compared.

Law and Law [5] used the large activation energy asymptotic method to study the ignition of a pre-mixed combustible mixture on a hot plate. They noticed that there exist self-similar solutions for the flow with chemical freezing limit and found a local similar solution in the inner diffusion reaction zone. Under the condition of laminar natural convection, Ono et al. [6] theoretically and experimentally studied the ignition problem of combustibles flowing through an electrically heated vertical plate. The results obtained from their experimental data showed good agreement with the theoretical prediction of a numerical analysis of the fundamental equations. The results were illustrated combining the ignition and surface height, surface and ambient temperature, pressure and combustible properties.

Chen and Faeth [7] described the theoretical study of igniting combustible gases through heated vertical surfaces. The dimensionless governing equations were solved numerically. The progress of combustion was clarified with respect to the changes in velocity, temperature, reaction rate and concentration. Berman and Ryazanstev [8] studied the ignition of combustible gas on a semi infinite flat heated plate. They used matched asymptotic expansions for the high activation energy limit to obtain an expression for the ignition distance. Here analytical expressions for the ignition distance were also presented to describe the problem.

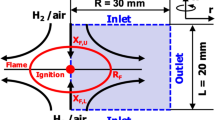

Melguizo-Gavilanes et al. [9] numerically and experimentally investigated the buoyancy-driven flow and reaction mechanism of hydrogen-air mixture on a quickly heated surface. The ignition system was described by utilizing preferred velocity, species and temperature terms. Boeck et al. [10] also carried out numerical simulation and performed experimental investigation to examine the combustion of premixed hydrogen and air produced by a hot glow plug. However, Treviño and Méndez [11] analyzed the ignition phenomenon of combustible mixture of hydrogen, oxygen and nitrogen by employing asymptotic analysis techniques. Campbell [12] examined the natural convection in a spherical vessel to explore the action of exothermic chemical relation. Iglesias et al. [13] described the behavior of thermal explosion in a spherical vessel under the natural convection.

Sparrow et al. [14] discussed the combined forced and free convection flow of a non-isothermal body which subjected to a non-uniform free stream velocity. They used similar solution to solve laminar boundary layer equations and showed that the boundary-layer solution may be expanded into a power series in Gr/Re2. They also found that the parameter Gr/Re2 controlling the relative importance of the forced and free convection. The velocity and temperature functions were described on the graph for the Prandtl number Pr = 0.7 and different values of Gr/Re2. Merkin [15] used series expansion method to solve the non-similar boundary layer equations and obtained two series solutions. One of which was valid when ξ go to zero and occurred at the leading edge and another was arising when ξ go to an asymptotically large value.

A local similarity method was used by Lloyd and Sparrow [16] for an isothermal vertical plate. Numerical results were exhibited for Prandtl numbers of 0.003, 0.01, 0.03, 0.72, 10 and 100. In addition, provide detailed information about liquid metals as well as gases and common liquids. Roy and Parvin [17] studied boundary layer flow of combustible gas under mixed convection. They used perturbation method for smaller values of ξ and asymptotic method for larger values of ξ.

A combined free and forced convective flow was investigated by Soundalgekar et al. [18] for a semi-infinite vertical plate where they derived series solution in power of Gr/Re2 and the resulting similarity equations were solved numerically. A set of continuous transformations of the boundary layer equations were introduced under mixed convection flow by Hunt and Wilks [19]. The method displayed the evaluation of the boundary layer between the similarity regimes. The method presented the boundary layer evaluation between similarity regimes.

The motivation of this paper is to reveal the ignition distance location and the flow properties of the combined forced and natural convection flow. In order to achieve the target, we sequentially formulate the forced and natural convection problems. Finally, a continuous transformation is introduced to circumvent the inconvenient switch between the forced and natural convection. Solutions of the conservation equation are acquired by the method of finite difference. A comparison is made between forced and mixed convection for small values of ξ as well as natural and mixed convection which are in excellent agreement for large values of ξ. The behavior of ignition distance with the modification of the momentum, thermal, and concentration boundary layers at the plate is investigated. Numerical solutions are displayed and discussed in relation to streamlines, isotherms, and concentrated isolines. Profile of the dimensionless velocity, temperature and concentration distribution for oxidizer and fuel are shown graphically for several values of physical parameters.

Section 2 deals with the mathematical formulation of the problem and asymptotic analysis is described to find the ignition distance location under Sect. 3. Numerical solutions methodology is explained under in Sect. 4. In Sect. 5, a detailed analysis of the outcomes is exhibited for physical parameters. Section 6 summarizes the article with concluding remarks. Reference section is attached at the end of the article.

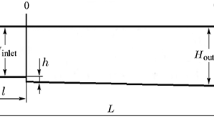

2 Mathematical formulation

In the presence of the gravitational field, a steady, 2D laminar boundary layer flow has been considered over a heated inclined surface. The flow parameters such as velocity, pressure, and density of the flow for each point are independent of time. The physical configuration and coordinate system are shown in Fig. 1. Here the specific heat of the species under constant pressure (cp) is assumed to be constant. It is also considered that the radiative heat transfer, Soret and Dufour effects are negligible. The fuel (F) reacts with oxidizer (O) following an irreversible exothermic reaction as follows:

That is, the fuel is transformed to the product without any intermediate change.

Additionally, the reacting chemical is assumed to be a mixture of ideal gases, in which the relations ρμ = ρ∞μ∞ and ρλ = ρ∞λ∞ hold and the values of ρμ, ρλ, ρDF and ρDO are kept constant.

Based on the above conjectures, the governing equations of boundary-layer flow on the inclined surface are expressed as follows [20, 21]

where (x, y) the distances along and normal to the surface, (u, v) the velocity components along the x and y directions, T the temperature, ρ the density, p the pressure, μ the viscosity, λ the thermal conductivity and Di (i = F, O) the mass diffusivity of the combustible gas mixture within the boundary layer, the universal gas constant and the acceleration due to gravity are symbolized by g and R. Also, α denotes the angle of inclination of the surface towards the gravitational field, specific heat of combustion is represented by q, the fuel and oxidizer mass fractions are symbolized by YF and YO, the molecular weights of fuel and oxidizer are denoted by WF and WO.

In Eqs. (4)‒(6), the reaction term is represented by the following formula,

here B the frequency factor, γ the temperature exponent, ni (i = F, O) the reaction order of fuel and oxidizer and E the activation energy.

The corresponding boundary conditions are

where U0 is the free stream velocity, T∞ and Tw the ambient temperature and surface temperature with Tw > T∞ and YF,∞ and YO,∞ represent the ambient fuel and oxidizer mass fractions.

2.1 Forced convection regime

To get a system of equations we introduce the following conversions that applies to the entire regime of forced convection

where χ = νOWO/WF stands for the mass stoichiometric ratio between oxidizer and fuel. The scale factor along horizontal axis x is U02/ g, temperature scale \(T = q\tilde{T}/c_{p}\), Mass fraction scale for fuel YF = yF, Mass fraction scale for oxidizer YO = yOχ.

From Eq. (11) it is clear that when the forced convection velocity U0 is very high and the buoyancy force is relatively small then the value of ξ is small. So, for the forced convection flow the boundary layer is formed near the leading edge.

The stream function ψ(x, y) is described by the following format,

Introducing the above dimensionless variables from Eqs. (11)−(12) into the governing Eqs. (3)-(6) gives the following dimensionless form of the equations

where the dimensionless reaction term is presented as follows

where n = nF + nO and in the above equations the dimensionless parameters are defined as

Here, Pr is the Prandtl number, ScF the Schmidt numbers for fuel and ScO the Schmidt numbers for oxidizer, δ the non‒dimensional surface temperature, θA the non‒dimensional activation energy, A the non‒dimensional heat release parameter and Λ the non‒dimensional reaction parameter.

The boundary conditions (9) and (10) now become

where yF,∞ = YF,∞ and yO,∞ = YO,∞/χ.

2.2 Natural convection regime

The boundary layer in the natural convection regime is basically formed by the buoyancy forces. The following appropriate conversions are proposed for the natural convection regime

Using the above transformations, Eqs. (3)-(6) are reduced to the following form

with the boundary conditions

2.3 Mixed convection regime

For the propose of obtaining a system of equations relevant for both forced and natural convection, the coordinate transformations for mixed convection will be

It is evident from Eq. (29) that when ξ is small the above transformations become similar to that of the forced convection and when ξ is large they reduce to that of the free convection flow. Combining the relations given in Eqs. (29), the gossverning Eqs. (3)-(6) are

Subject to the boundary conditions

3 Asymptotic analysis

3.1 Chemically frozen limit

The response of most pre-ignition regions is very weak. From this physical way of thinking, changes in flow characteristics along the flow direction can be minimized. Firstly, a solution under the chemical freezing limit of the standard asymptotic method is required. Secondly, considering \(\theta_{A} \to \infty\), that means, the reaction condition is negligible. For all of these reasons, the flow field is completely frozen. Under the above consideration the governing Eqs. (30)-(33) gives the following form of the equations

subject to the conditions (34) and (35).

3.2 Weakly reactive state

Ignition is more likely to occur near high temperature walls (\(\hat{\eta }\) → 0), because of large activation energy. With this criterion, we set up the following coordinate transformation,

where

Then, obtaining the new form of energy equation applying the transformation (40)

where

The boundary conditions take the following form

According to Eq. (40), as \(\hat{\eta }\) → 0 the transformed coordinate ζ becomes

When \(\hat{\eta }\) → 0 and ζ → 0, the stretched inner coordinate considered as

Here, \(\phi^{^{\prime}}_{fz,w} = {{\partial \phi_{fz} \left( {\xi ,0} \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\partial \phi_{fz} \left( {\xi ,0} \right)} {\partial \hat{\eta }}}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {\partial \hat{\eta }}}\). The magnitude of \(\phi^{\prime}_{fz,w}\) is negative for the problem of interest. The perturbation parameter is symbolized by \(\varepsilon\) and expressed as \(\varepsilon = {{T_{w}^{2} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{T_{w}^{2} } {\theta_{A} }}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {\theta_{A} }}T_{\infty } \left( {T_{w} - T_{\infty } } \right)\).

The temperature in the inner region is expressed as follows

According to the coordinate σ, the inner expansion (47) becomes

After substituting Eq. (48) into (42), as \(\hat{\eta }\) → 0 we have

Conspicuously, the diffusion term \(\frac{{\partial^{2} \tau }}{{\partial \sigma^{2} }}\) of Eq. (49) is more dominating than the other term on left. In Eq. (49), the diffusion term and the reaction term are balanced in the weak reaction condition. Therefore, Eq. (49) is simplified to

where

The boundary conditions are

The condition (52) can be determined by matching the inner and outer solutions which was performed by Law and Law [5] and Rangle et al. [22].

3.3 Ignition criterion

In Ref. [3], it is concluded that two solutions are found for the condition Δ < 1, however, there is no solution for Δ > 1. That is why the ignition must occur for Δ = 1. As the DamkÖhler number is the ratio of the chemical effect to transport effect, the condition ΔI = 1 represents the balance between the reaction rate and the convective mass transport rate. Assuming,

Equation (51) yields

Combining (54) and (11), the first ignition location in dimensional form is

It is worthy of mentioning that the ignition distance location, xI, depends on the wall temperature, Tw. In this work, the critical temperature is the minimum temperature that is needed for starting ignition. When the ignition is first occurring, then in the presence of fuel and oxidizer the ignition temperature being high and ignition distance become small rapidly. At this stage the value of ignition distance is approximately zero. Sheu and Lin [4] analyzed that when Tw is greater than a critical value, ignition would occur simultaneously over the entire surface. So, the ignition could happen for this minimum critical temperature.

4 Numerical solutions

In this study, Fortran 90 programming language has been used for numerical simulation. Equations 30 and 33 are solved via the finite difference method. According to said method, we initially adopt the following assumptions to transform the partial differential Eqs. (30)-(33) into a system of second-order differential equations,

Substituting Eq. (56) into the Eqs. (30)-(33), we obtain

The corresponding boundary conditions are

Here we consider,

Now, we use the central difference approximation along the η direction and the backward difference for the ξ direction. Then, the tri‒diagonal algebraic equation system is expressed as the following form

Here, Wi, j represents the unknowns such as the functions u, ϕ, ΦF and ΦO. The subscript \(k = \overline{1,4}\) represents the momentum equation, the energy equation and the species equations for fuel and oxidizer respectively. Moreover, \(i = \overline{1,M}\) and \(j = \overline{1,N}\) are the corresponding grid points in ξ and \(\hat{\eta }\)-directions, respectively. Keeping j fixed, the well-known Thomas algorithm [23] is used to solve the tri‒diagonal Eq. (64) for i (= 1, 2, 3,…, M). Then express the result in j directions. Until the steady state is reached, the solution is determined from ξ = 0.0 at each step in the ξ direction. The convergence criterions are selected so that the difference between the values of \(h\left( {\xi ,\hat{\eta }} \right)\) in two successive iterations is less than 10‒5. For the present numerical simulation, the final mesh sizes are considered as Δξ = 0.01, \(\Delta \hat{\eta }\) = 0.025. Along ξ direction, the computation is carried out starting at ξ = 0.0 and proceeding to ξ = 50.

5 Results and discussion

Using the finite difference method, the governing conservation equations of the two dimensional, steady, laminar boundary layer flow on the heated inclined plate under the three discrete modes are solved. For the mixed convection, the natural convection is of comparable order of forced convection. We thus define coordinate variable ξ (= g/U02x) in the ratio of gravitational force and convection velocity.

It indicates that when the forced convection velocity U0 is very high and the buoyancy force is relatively small then the value of ξ is small. So, for the forced convection flow the boundary layer is formed near the leading edge. In addition, when the buoyancy force is dominant, the value of ξ is large enough and the boundary layer develops far from the leading edge which is known as natural convection.

According to the above concept, we are trying to verify the accuracy of numerical results solving the forced convection Eqs. 14, 17, natural convection Eqs. 23, 26 and mixed convection Eq. 30, 33. For small values of ξ, mixed convection behaves like forced convection and large values of ξ, mixed convection acts like natural convection. The variation of physical parameters such as Prandtl number (Pr), Scmidth number (Sc), angle of inclination of the surface (α), and reaction parameter (Λ) on the velocity, temperature, fuel and oxidizer concentration profiles are illustrated. The effect of varying physical parameter on the streamlines, isotherms and isolines of fuel and oxidizer concentration are also demonstrated. Finally, observe the relationship between ignition and related system parameters through graphical methods.

Here the properties of the butane-air mixture are taken as nF = 0.15, nO = 1.65, WF = 58 g/mol, WO = 32 g/mol, YF,∞ = YO,∞ = 0.2, γ = 0.75, νO = 6.5, q = 4.2 × 107 J/kg, cp = 1046 J/(kg K), p = 1 atm [4, 24], Pr = 0.7, ScF = ScO = 0.65, θA = 34.3, T∞ = 293 K, Tw/T∞ = 3.9 [7], g = 9.8 m/s2, B = 3.4 × 108, μ∞ = 10−5 kg/(ms) and Λ = 1.84 × 105.

In Figs. 2a and c we demonstrate the numerical solutions considering the parameters from Chen and Faeth [7] with the aim of validating the present solutions. Chen and Faeth [7] explained their numerical solution via graphical method. They don’t give any experimental data. For this reason we choose graphical method to verify the numerical solutions.

Compare a velocity, b temperature and c concentration profiles with Chen and Faeth [7]

It is observed that if we assume α = 0.0 in Eq. (23), nO = 0.0 and γ = 0.0 in Eq. (23), the model of this study will adopt the form of [7]. Furthermore, the boundary conditions (27) and (28) are considered as yF,∞ = yO,∞ = 1.0 and F ' → 0 at Y → . It is observed from Figs. 2a and c that the current solution is in good agreement with Chen and Faeth's solution [7].

5.1 Effect on velocity, temperature, fuel and oxidizer concentration profiles for different physical parameters.

Figure 3a and d shows the comparison of forced convection and mixed convection for different values of coordinate variables ξ. It is noted that figures are drawn considering the relations between forced and mixed convection for small values of ξ, while Pr = 0.7, Sc = 0.65 and α = 45°.

The results show that for small ξ, forced convection and mixed convection have good consistency. The relations between natural and mixed convection are shown in Figs. 4a-d for large values of ξ. It can be clearly seen from the figure that the solutions are very consistent for large values of ξ, when Pr = 0.7, Sc = 0.65 and α = 45°.

The impact of Prandtl number, Pr, on the velocity, temperature, fuel concentration and oxidizer concentration are illustrated in Figs. 5a-d. The Prandtl number (Pr = μcp/ λ) is defined as the dimensionless ratio between kinematic viscosity and thermal diffusivity. It is seen that the increase of the Prandtl number means the increase of the kinematic viscosity or a decrease of the thermal diffusivity. If the momentum diffusivity increases, then the velocity of the fluid is increasing gradually. Accordingly, the momentum boundary layer thickness decrease. On the contrary, increase of the Prandtl number, Pr, the thickness of the thermal boundary layer. The concentration boundary layer for fuel rising with mounting value of Pr till η = 2.2. But after η = 2.2 reversal scenario has occurred. Likewise, with an increasing value of Pr up to η = 1.8, the concentration boundary layer for oxidizer increases. But there is an opposite situation after η = 1.8.

The effect of the Schmidt number, Sc, on the velocity, temperature, fuel concentration and oxidizer concentration is depicted in Figs. 6a-d. The results show that the momentum and thermal boundary layer of the higher Sc value remain unchanged, but the concentration boundary layer is significantly reduced. The Schmidt number (ScF = μ /ρDF, ScO = μ /ρDO) is a dimensionless number, which is defined as the ratio of motion diffusivity to mass diffusivity. We see that Sc becomes higher for increasing value of kinematic viscosity or decreasing of mass diffusivity. Figure 6c and d present that with an increasing value of Sc within the range of = 0.0 to 1.25, the concentration boundary layer for fuel decreases. But it is exchange it’s characteristic after η = 1.25. Similarly, the concentration boundary layer for oxidizer boosts, with a higher value of Sc up to η = 1.15. But there is an opposite scene after η = 1.15.

Figures 7a and 6d exhibite the impact of the angle of inclination, α on velocity, temperature, fuel concentration and oxidizer concentration. The results show that with the increase of the inclination angle, the velocity, the boundary layer flow rate of the fuel and oxidant concentration decrease, and the temperature distribution is contradictory. The thermal boundary layer increases with the increases of the values of α. This is because as the inclination angle increases, the influence of buoyancy force due to thermal changes decreases by a factor of cos(α) as the plate is inclined. It can be noted that if α = 0 the issue reduces to the vertical flat plate and when α = 30, 45, 60 the problem decreases to the inclined flat plate.

Figures 8a and d exhibit the impact of the variation in the value of Λ on the velocity, temperature and concentration profiles, when the ambient temperature is fixed. It can be understood from Eq. (19) that the parameter of the reaction, Λ depends on the frequency factor, B. Collisions between the molecules of the combustible occurs with the increasing value of B. Heat is produced for this reason. This has a significant impact on the rate of reaction and then the reaction rate becomes higher. Reaction parameter, Λ is proportional to the dimensionless reaction rate, ω. Therefore, the increase in Λ produces an increase in the reaction rate that increases the momentum boundary layer and the thermal border layer thickness. On the other hand, the concentration boundary layer for fuel and oxidizer reduce with for the higher value of reaction parameter.

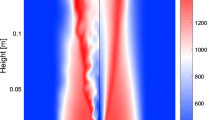

5.2 Illustration of streamline, isotherms and isolines of concentration for different physical parameters

Figures 9a−d show the influence of Prandtl number on the streamlines, isotherms, isolines of fuel and isolines of oxidizer concentration, while Sc = 0.65, α = 45°and ξ = 30. It is seen that the momentum and the concentration boundary layers become thicker for higher values of Pr. However the thermal boundary layer decreases as the Prandtl number increases. It is because when Pr is higher, the produced heat is transferred away from the surface at a lower rate.

The pattern of streamlines, isotherms, isolines of fuel and isolines of oxidizer concentration for different values of Schmidt number is exhibited in Figs. 10a-d, taking Pr = 0.65, α = 45° and ξ = 30. It is seen from the figure that for higher Sc values, the momentum boundary layer and thermal boundary layer are almost unchanged. On the other hand, the concentration boundary layer is significantly reduced.

Figures 11a−d depict the variation of streamlines, isotherms, isolines of fuel and oxidizer isolines of concentration for different values of angle, α, while Pr = 0.7, Sc = 0.65 and ξ = 30. It is evident from the figures that as the value of the inclination angle α of the plate increases, the momentum boundary layer and the concentration boundary layer become thicker, and the thermal boundary layer becomes thinner. This is why the increase in the inclination with respect to the horizontal direction enhances buoyancy force.

The variation of reaction parameter, Λ on streamlines, isotherms, isolines of fuel and isolines of oxidizer concentration are illustrated in Figs. 12a, d, taking Pr = 0.65, Sc = 0.65, α = 45° and ξ = 30. The reaction rate, ω increases for higher values of Λ. So, heat is generated from the chemical reaction near the surface. It is seen that the higher values of reaction parameter, thicken the momentum and concentration boundary layers as well as the thermal boundary layer.

5.3 Effects of various physical parameters on the ignition distance profile

Using the ignition distance XI,ξ=0 for Pr = 0.7, Sc = 0.65 and T∞ = 293 K, the dimensionless ignition distance XI/XI,ξ=0 is introduced here.

The effect of Pr on the value of XI/XI,ξ=0 is shown in Fig. 13. Results indicate that the ignition distance diminishes for higher values of Pr. As Prandtl number is the ratio of the momentum diffusivity to the thermal diffusivity, higher value of Pr causes smaller heat diffusion from the surface to the nearby region. So, a larger Prandtl number induces faster ignition.

According to Fig. 14, a slightly increased wall temperature causes a considerable reduction in ignition distance. In the initial phase of the ignition phenomenon, the wall temperature is low and the effect of the combustion on the process is negligible. For this reason, ignition distance is maximized. The higher values of the wall temperature determine the growth of the ignition region. In this study, we have been considered 3.9 as a critical value of dimensionless ignition temperature. In Fig. 14, we are numerically investigated that if the value of Tw /T∞ > 3.9 then the value of XI/XI, ξ=0 is gradually decreasing. On the other hand, the value of XI/XI, ξ=0 is competitively large when Tw /T∞ < 3.9. It is also noticeable that the magnitude of XI/XI,ξ=0 is very small for Tw /T∞ > 5.2. As a result, it can be understood that ignition occurs simultaneously over the whole surface. Furthermore, we calculate the asymptotic results and it is seen that the asymptotic and numerical solutions qualitatively agree well.

An increase in the reaction parameters, Λ, leads to an increase in the reaction rate and plays a role in reducing the ignition distance. Figure 15 presents the effect of the reaction parameters of the ignition distance.

6 Conclusions

The problem of thermal ignition of a combustible boundary-layer flow over an inclined hot plate has been examined under mixed convection. The governing boundary layer equations are converted to a dimensionless form. Then the obtained nonlinear systems of partial differential equations are numerically solved by the finite difference method. A comparison is made between forced and mixed convection for small values of ξ as well as natural and mixed convection which are in excellent agreement for large values of ξ. The obtained results are presented graphically and it is pointed out that.

-

1

As the value of the dimensionless coordinate variable increases, the thickness of the temperature boundary layer and the concentration boundary layer both decrease, while the thickness of the momentum boundary layer increases.

-

2

For a higher Prandtl number, the momentum boundary layer and the concentration boundary layer become thicker, but as the Prandtl number increases, the thermal boundary layer decreases.

-

3

Because of higher Schmidt numbers, the momentum boundary layer and thermal boundary layer are almost unaffected. At the same time, the concentration boundary layer is significantly reduced.

-

4

For the sake of higher inclination angles, the thickness of the momentum boundary layer and the concentration boundary layer are noticeably increased.

-

5

For increasing values of the reaction parameter, thicken the momentum and concentration boundary layers, as well as the thermal boundary layer.

The paper can be extended to study the effect of time and radiation. This may help in investigating ignition distance location more accurately.

Abbreviations

- B :

-

Frequency factor (m3/kg s)

- c p :

-

Specific heat capacity of the combustible (J/ kg K)

- D :

-

Molecular mass diffusivity (m2/ s)

- E :

-

Activation energy (J/ kg)

- F, f, h :

-

Dimensionless stream function

- g :

-

Acceleration due to gravity (m/ s2)

- N :

-

Total reaction order nF + nO

- n F :

-

Reaction order of fuel

- n O :

-

Reaction order of oxidizer

- P :

-

Pressure (N/ m2)

- Pr :

-

Prandtl number

- q :

-

Specific heat of combustion (J/ kg)

- R :

-

Universal gas constant (J/ kg K)

- Sc :

-

Schmidt number

- T :

-

Temperature (K)

- \(\tilde{T}\) :

-

Dimensionless temperatur

- T ∞ :

-

Ambient temperature (K)

- U 0 :

-

Free stream velocity (m/ s)

- u :

-

Streamwise velocity component (m/ s)

- v :

-

Transverse velocity component (m/ s)

- W :

-

Molecular weight (kg/ mol)

- w :

-

Rate of chemical reaction (kg/ m3s)

- x :

-

Distance along the surface (m)

- y :

-

Distance normal to the surface (m)

- Y :

-

Dimensionless transverse coordinate

- Y F, y F :

-

Mass fraction of fuel

- Y O, y O :

-

Mass fraction of oxidizer

- Y F , ∞ :

-

YF,∞: Ambient mass fraction of fuel

- Y O , ∞ :

-

Ambient mass fraction of oxidizer

- α :

-

Angle of inclination

- χ :

-

Stefan-Boltzmann constant (W/ m2 K4)

- γ :

-

Temperature exponent

- δ :

-

(TW − T∞)/T∞

- ε :

-

Perturbation parameter \({{T_{w}^{2} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{T_{w}^{2} } {\theta_{A} }}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {\theta_{A} }}T_{\infty } \left( {T_{w} - T_{\infty } } \right)\)

- Φ :

-

Dimensionless Mass fraction

- Λ :

-

Reaction parameter

- η, \(\hat{\eta }\) :

-

Dimensionless transverse coordinate

- θ, Θ :

-

Dimensionless temperature

- θ A :

-

Dimensionless activation energy

- λ :

-

Thermal conductivity (W/ m K)

- μ :

-

Viscosity (kg/m s)

- ν :

-

Kinematic viscosity (m2/ s)

- ξ :

-

Dimensionless streamwise coordinate

- ψ :

-

Stream function

- ρ :

-

Density (kg/ m3)

- σ :

-

Stretched inner coordinate

- τ :

-

Perturbed temperature

- ω :

-

Dimensionless rate of chemical reaction

- F :

-

Fuel Fuel

- fz :

-

Chemically frozen state

- I :

-

Ignition state

- in :

-

Inner expansion

- O :

-

Oxidizer

- w :

-

Hot surface

- ∞ :

-

Ambient condition

- ~ :

-

Dimensionless variable

- ′:

-

Differentiation with respect to η

References

Toong TY (1957) Ignition and combustion in a laminar boundary layer over a hot surface. Symp (Int) Combust 6(1):532–540

Lin MC, Sheu WJ (1994) Theoretical criterion for ignition of a combustible gas flowing over a wedge. Combust Sci Tech 99:299–312

Law CK (1978) On the stagnation point ignition of a premixed combustible. Int J Heat Mass Transf 2:1363–1368

Sheu WJ, Lin MC (1997) Ignition of non-premixed wall-bounded boundary-layer flows. Combust Sci Tech 122:231–255

Law CK, Law HK (1979) Thermal-ignition analysis in boundary-layer flows. J Fluid Mech 92(1):97–108

Ono S, Kawano H, Niho H, Fukuyama G (1976) Ignition in a free convection from vertical hot plate. Bull JSME 19(132):676–683

Chen LD, Faeth GM (1981) Ignition of a combustible gas near heated vertical surfaces. Combust Flame 42:77–92

Berman VS, Ryazanstsev YS (1978) Ignition of a gas in a boundary layer at a heated plate. Fluid Dyn 12:758–764

Melguizo-Gavilanes J, Boeck LR, Mével R, Shepherd JE (2017) Hot surface ignition of stoichiometric hydrogen-air mixtures. Int J Hydrog Energy 42:7393–7403

Boeck LR, Melguizo-Gavilanes J, Shepherd JE (2019) Hot surface ignition dynamics in premixed hydrogen-air near the lean flammability limit. Combust Flame 210:467–478

Treviño C, Méndez F (1991) Asymptotic analysis of the ignition of hydrogen by a hot plate in a boundary layer flow. Combust Sci Technol 78:197–216

Campbell AN (2015) The effect of external heat transfer on thermal explosion in a spherical vessel with natural convection. Phys chem chem phys 17:16894–16906

Iglesias I, Sánchez AL, Williams FA, Liñán A (2015) Effects of natural convection on thermal explosions in spherical vessels, Proceedings of the 25th ICDERS 2–7, Aug, Leeds, UK

Sparrow EM, Eichorn R, Gregg JL (1959) Combined forced and free convection in a boundary layer flow. Phys Fluids 2:319–328

Merkin JH (1969) The effect of buoyancy forces on the boundary layer flow over a semi-infinite vertical flat plate in a uniform stream. J Fluid Mech 35:439–450

Lloyd JR, Sparrow EM (1970) Combined forced and free convection flow on vertical surfaces. Int J Heat Mass Transf 13(2):434–438

Roy NC, Parvin S (2019) Laminar boundary layer flow of a combustible gas over a semi-infinite porous surface. SN Appl Sci 1:1656

Soundalgekar VM, Takhar HS, Vighnesam NV (1988) The combined free and forced convection flow past a semi-infinite vertical plate with variable surface temperature. Nucl Eng Des 110:95–98

Hunt R, Wilks G (1981) Continuous transformation computation of boundary layer equations between similarity regimes. J Comput Phys 40(2):478–490

Sheu WJ, Lin MC (1996) Thermal ignition in buoyancy-driven boundary layer flows along inclined hot plates. Int J Heat Mass Transf 39(10):2187–2190

Roy NC (2019) Natural convection flow of a combustible along inclined hot plates. Therm Sci Eng Prog 11(6):409–416

Rangel RH, Fernandez-Pello AC, Treviño C (1986) Gas phase ignition of a premixed combustible by catalytic and non-catalytic cylindrical surfaces. Combust Sci Tech 48(1–2):45–63

Blottner FG (1970) Finite difference methods of solution of the boundary-layer equations. AIAA J 8(2):193–205

Sheu WJ, Lin MC (1997) Ignition of accelerated combustible boundary-layer flows under mixed convection. Combust Sci Technol 130(1–6):1–24

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Parvin, S., Roy, N.C. & Gorla, R.S.R. Thermal ignition of a combustible over an inclined hot plate. SN Appl. Sci. 3, 352 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-021-04363-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-021-04363-4