Abstract

Temperature-dependent diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS) measurements have been carried out on the polycrystalline sample TiO2. Important values from optical parameters such as band gap (Eg), Urbach energy (EU), and Urbach focus (E0) have been estimated in the range of 300–450 K. In order to understand the experimental value of band gap (Eg) of TiO2, i.e., obtained from DRS, a first-principle calculation has been performed. The dependency of EU and the slope of exponential tails (β1, β2) of the density of states has also been studied which determines the distribution of exponential tails near the valence and conduction bands in semiconducting oxides. The behavior of optical band gap and EU has also been investigated with the influence of temperature using Cody model. From the temperature dependence of band gap measurements, the value of thermodynamical parameter such as Debye temperature (θD) has also been estimated. Thus it appears that the temperature-dependent optical absorption spectroscopy is very powerful and economical tool to probe the electronic structure near band edge and also to estimate the important thermodynamical parameter.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Optical properties of titanium dioxide (TiO2) have been the central goal of various intensive investigations over the past few years [1,2,3]. The major objective is to understand the behavior of optical absorption spectra with the application of temperature [4, 5]. Diffuse reflectance spectrometer (DRS) is an effective tool to understand the absorption spectra as a function of doping or temperature. The absorption spectra obtained from DRS contain three possible transitions: (1) main absorption spectra which give the information of optical gap [6, 7], (2) near absorption edge also called Urbach tail showing amount of disorder present in samples [4], and (3) lower absorption spectra which confirm the presence of defect inside the sample [8, 9]. To explore the optical absorption spectra which may be affected from various parameters like temperature, structural transition, doping, etc., an influential work has been done to shape our understanding as to how band gap and disorder varies on semiconducting materials [4, 10]. To understand how the thermal and structural components of the disorder exclusively contribute to the comprehensiveness of the optical absorption tail, Cody et al. [11] accomplished an experimental inquiry of their specific roles.

TiO2 is well known for its high stability, abundance, nontoxicity, and there has been a tremendous amount of application in semiconducting devices. Keeping this view studies has already been done, extending from their synthesis and characterization to atomic scale, i.e., experimental and theoretical investigations [1,2,3]. Taking this into the account, our main aim in the manuscript is to understand the variation of disorder and optical band gap with the application of temperature via diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS). According to Jalalov et al. [12], the behavior of optical absorption can also be explained by the density of electronic states.

where A is the proportionality constant which is independent of the frequency of an absorbed photon; ε0 is the energy at the node of the tails on valence and conduction bands; |B|2 is the dispersion of the matrix element for the electronic transitions; and g (ε) and g (ε + ħω) are the distributions of the DOS consistent of initial and final states of electrons involved in optical transitions during absorption of photons with energy ħω. For the disordered system, an exponential tail behavior has been seen in the density of states near to valance and conduction edge. Temperature is one of the important constraints which play a key role in producing thermal disorder in semiconducting oxides. The decrease in band gap on semiconducting materials is observed with increasing temperature, and it is expected in general as per the Varshni’s [13] relation as follows:

where Eg is the energy gap which may be direct (Egd) or indirect (Egi), Eg(0) is the energy gap at 0 K, and γ and β are constants. It is proposed that the fitting parameter β in Eq. 2 is related to the Debye temperature (θD) [14] as:

In this case, it is found that β = θ/2 where θ is the effective Einstein vibrational frequency in temperature units of the phonon spectrum in the material.

Optical spectroscopy is a tool which can tell about not only the optical band gap of semiconducting materials but also the disorder in the form of Urbach energy as well as various defects [8] present in semiconducting materials. Keeping this in view, here we have performed temperature-dependent DRS and report its dependency on optical band gap [4], Urbach energy [10], and Urbach focus on TiO2 [1, 15, 16]. It is observed that Urbach energy shows opposite behavior from band gap, i.e., with the increase in temperature optical band gap decreases while due to change in optical spectra near absorption tail edge leads to increase disorder present in sample [4]. It is clear from the experimental evidence that Urbach–Martienssen [17, 18] (U–M) tails in the optical absorption spectra showing the variation of disorder produced with the application of temperature as well as variations of band gap with Urbach energy have also been investigated.

2 Experimental and theoretical details

2.1 Structural characterizations

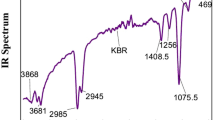

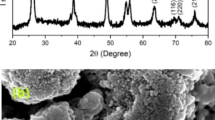

Commercial anatase TiO2 powder of Alfa Aesar with purity 99.999% has been used for characterization. In order to examine the structural phase purity, X-ray diffraction (XRD) experiment has been carried out on Bruker D8 diffractometer equipped with Cu target having LynxEye detector [6, 19,20,21]. The high-temperature X-ray diffraction measurements were performed to confirm the structural phase transition in the prepared samples. Jobin–Yvon Horiba micro-Raman spectrometer was used for Raman measurements. The micro-Raman spectrometer consists of an argon ion laser as light source.

2.2 Temperature-dependent diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS) measurement

The optical band gap of prepared sample has been measured by using DRS measurements [6,7,8]. These measurements have been taken in the 200–800 nm wavelength range using Cary-60 UV–Vis–NIR spectrophotometer having Harrick Video-Barrelino diffuse reflectance probe in the temperature range of 300–450 K [22].

2.3 Theoretical methods

The first-principles calculations are executed using FP-LAPW [23] approach and implemented in WIEN2k code [8, 24, 25]. The Kohn–Sham equations [26, 27] were solved self-consistently using FP-LAPW method. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA + U) has been used for DFT calculation. In the present studies, we have used structural parameters from experimental X-ray diffraction analysis (experimental data). Keeping this in view, we have not used lattice relaxation for calculation. We have taken generalized gradient approximation (GGA + U) as an exchange–correlation potential with U = 5 eV. During calculations, we have used RMTKmax = 7, where Kmax is the plane wave cutoff and RMT is the minimum of all atomic sphere radii (Muffin-tin radii). We have sensibly selected the muffin-tin radii (MT) 1.93 and 1.74 a.u. for Ti and O, respectively. When the total energy of given structure is stable within 10−3 mRy, it is believed that the self-consistent calculations are converged. The k-mesh size of 5 × 5 × 3 has been used in calculation.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Structural characterization and phase purity

Figure 1a shows the powder X-ray diffraction pattern for the prepared sample. The obtained X-ray diffraction data are indexed considering the space group I41/amd, and no impurity peaks are observed, which confirms the structural phase purity of the prepared sample. Further Raman spectra of anatase TiO2 have been recorded which is shown in Fig. 1b. It is clear from Raman spectra that B1g, A1g, and Eg modes confirm the presence of anatase phase with space group I41/amd.

3.2 Diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS)

We have investigated the optical absorption spectra for TiO2 using DRS technique. The spectra acquired from DRS enlightened through Kubelka–Munk [28, 29] equation.

where \(F(R_{\infty } )\) is the Kubelka–Munk function. Expression of Kubelka–Munk function can be written as:

In order to estimate the Eg, the obtained absorption coefficient is altered into Tauc equation [30, 31] and plotted in Fig. 2.

Here in Eq. 6 we have used the values of n = 1/2 for an indirect transition [4, 7, 10] to determine the optical gap of TiO2 as it is proposed to be an indirect band gap material. Using Tauc fitting [30], we have obtained experimental bandgap of TiO2 is 3.21 eV.

3.2.1 First-principle investigation (DFT calculations)

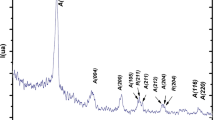

To confirm the type (direct or indirect) of band gap present in anatase TiO2, we have performed DFT calculations, and from band structure, it is clear that anatase phase of TiO2 shows indirect band gap of 3.21 eV shown in Fig. 3. As DRS shows experimental optical band gap Eg = 3.21 eV, to confirm this, we have performed first-principle calculations using WIEN2k code with GGA + U (U = 5 eV). We have taken experimental structural parameters and used them directly for the band gap calculations. As per calculated experimental band gap, which is around 3.21 eV, and to match this value of band gap, we have taken U = 5 eV. For a real system, the value of Coulombic interaction (U) is generally avoided in case of GGA calculation (i.e., U = 0), and hence, the value of experimental band gap of the real system does not match. However, in terms of GGA + U, the value of Coulombic interaction is taken care of to match experimental band gap. This extra Coulombic interaction also tells about the behavior of a real system. Figure 4 shows partial density of states (PDOS) of TiO2 showing gap between valance band maxima (VBM) and conduction band minima (CBM) of 3.21 eV, i.e., band gap (Eg), which matches with experimental DRS results. In case of pure TiO2, the states near Fermi level are dominated by the O-2p and Ti-3d orbitals.

3.2.2 Temperature-dependent band gap

The optical band gap of semiconductors tends to decrease as the increased in temperature [4, 13]. Figure 5 shows the variation of band gap as a function of temperature. From Fig. 5, it is clear that with the increase in the temperature the band gap of TiO2 systematically decreases and consistent with earlier reports [1]. We have fitted experimental data with Varshni’s relation [13, 32, 33] Using this relation, one can estimate the values of fitting parameters γ and β which are functions of thermodynamical quantity like Debye temperature [14, 34]. Inset of Fig. 5 shows the variation of optical spectra (Kubelka–Munk plot) at different temperatures 300–450 K. A relationship between β and θD has been discussed by Manoogian et al. [14, 34] using Varshni’s relation. In the intermediate temperature region, the Einstein temperature θE is related to the Debye temperature θD and β by the relation of θE = (3/4)θD [14, 34] and β = θE/2, respectively. Hence, it is clear that the Varshni’s parameter (β) is related to Debye temperature (θD) as follows: β = (3/8) θD [14]. Debye temperature (θD) = (8/3)β ≈ 562 K, (where β = 211 K obtained from fitting).

According to Shojaee et al. [35], Debye temperature of TiO2 is around 557 K, while using Varshni’s fitting obtained from optical spectroscopy, Debye temperature has been found to be very close to reported value [36], which is around 562 K. Hence it is clear that temperature-dependent DRS provide not only the variation in optical properties but a tool to estimate the thermodynamic properties like Debye temperature.

3.2.3 Determination of band tail width (Urbach energy)

In semiconductors, the fundamental absorption edge below the energy band gap increases exponentially, and the absorption edge is known as the Urbach tail. To understand the behavior of Urbach tails in semiconducting materials, various extensive investigations have already been done over the past few decades. Intensive investigation has been done in studies, i.e., phonons [37, 38], impurities [39], excitons [15], and structural disorders [4], which are associated with the observed exponential tails in optical spectra. Urbach energy (EU) provides the information about the total disorder present in the sample [1, 39,40,41,42]. The contributions to the said energy may be due to various types of disorders such as thermal, polar, chemical, and structural defects.

In order to find the value of EU, we have taken the natural logarithm of F(R) with respect to provided photon energy. After taking natural logarithm of F(R), we will get a straight-line equation which is as follows:

and the obtained equation is compared with equation of straight line

where Urbach energy (EU) is equivalent to the inverse of slope of above equation [4, 10]. The distribution of the density of localized states in the tails of the valence and conduction bands has exponential energy dependence [12]:

where β1 and β2 are parameters controlling the slope of an exponential tails of the valence and conduction bands. \(g\left( {\varepsilon_{\text{v}} } \right)\) and \(g\left( {\varepsilon_{\text{c}} } \right)\) represents as a density of states, and \(N\left( {\varepsilon_{\text{v}} } \right)\) and \(N\left( {\varepsilon_{\text{c}} } \right)\) are no. of atoms in valence and conduction bands respectively.

According to Jalalov et al. [12], Urbach energy is inversely proportional to the slope of an exponential tail of valance and conduction bands, i.e., β1 and β2. Keeping this in view, partial density of states (PDOS) has been calculated to see the variation of conduction band and valance band near Fermi energy using experimental structure parameters. From room-temperature DRS measurement, the presence of disorder in system has been observed from various reports. Hence, it is quite possible to get exponential tail from theoretical model also. Figure 6a shows fitting of valence band decay for density of states near Fermi energy (valence band tail), and Fig. 6b shows fitting of conduction band decay for density of states near Fermi energy (conduction band tail). Interestingly, it is found that the value of inverse of β1 and β2 has been found in the range of meV which clearly indicates that the Urbach energy is inversely proportional to the slope of an exponential tail of valance and conduction bands. Figure 7 shows a schematic diagram with density of states and photon Energy, and it is clearly seen that disorder states (tail state) arise in between valance bands (VB) and conduction bands (CB). The change in the band gaps with increasing temperature can be described by the effect of lattice vibrations on the energy levels in given system. The temperature dependence of the band gap is determined by the density of states [12, 43] of the conduction band and valence band of the semiconductor. Due to the thermal broadening [44] of the density of states near the bottom of the conduction band and valence band reduces the band gap. The temperature dependence of the forbidden states of vibrational level may get allowed near CB and VB, and hence the density of states in the areas of constant edge of the conduction band and valence band has a stepped shape (shown in Fig. 7), i.e., allowed vibrational states near CB and VB for various temperatures like T1, T2, T3, etc.

The reciprocal of the slope of the obtained straight lines leads to determination of the Urbach energy EU. It is observed that, the values of EU in TiO2 were increased from ~ 100 to 220 meV with temperature range 300–450 K. Increasing EU with the application of temperature leads to increase in the disorder present in the sample. The disorder can introduce localized states at the conduction band maxima and valance band minima, which leads to increase the band tail width EU. Kranjčec et al. [45] calculated disorder free energy, i.e., Urbach focus (E0) and observed that at the structural phase transition the value of the E0 changes. The E0 is predicated to be the material constant related to the absorption edge in the absence of any type of disorder in the sample [11, 46]. The detailed discussion on the origin of the E0 is given by Guerra et al. [47]. Figure 8 shows variation of Urbach energy with the application of temperature with range 300–450 K. The value of Urbach focus [4] represents the disorder free energy (i.e. band gap at 0 K) and shown in the inset of Fig. 8. It is well known that the Urbach energy in solids is used to determine not only thermal disorder, but also structural and compositional disorders in semiconducting oxides like TiO2. Figure 9 shows the linear variation in between band gap and Urbach energy with the application of temperature as suggested by Cody model [11]. According to Cody et al. [11], it is found that band gap (\(E_{\text{g}}\)) and Urbach energy (\(E_{\text{u}}\)) show linear behavior which is as expressed:

where Eg(0, 0) and EU(0, 0) are the values of band gap and Urbach energy in a defect-free crystal at 0 K, \(< {\varDelta^{2} } >_{0}\) the zero-point uncertainty [11, 43, 48] in the atomic positions and from fitting the value of the displacement is around 0.05 Å2. It is also important to understand the importance of zero-point uncertainty in the atomic positions, and each real system represents harmonic oscillator model. Using harmonic oscillator, it is easy to estimate minimum oscillator energy (ground vibrational state) [49, 50] as well as \(< {\varDelta^{2} } >_{0}\) as follows:

Derivative of Eq. 13 will give minimum energy of the oscillator at a particular value of \(< {\varDelta^{2} } >_{0}\) is

where \(\hbar\) = Plank constant, \(m_{\text{osc}}\) = mass of oscillator, \(<{\varDelta^{2} }>_{0}\) = zero-point uncertainty in the atomic position [11], E0 = minimum energy of oscillator and \(\omega\) represents oscillating frequency. Here, D represents the second-order deformation potential [48], and this has been approximated ± 0.3 Rydberg/Å2 (or 4.08 eV/Å2) [11]. At zero thermal energy (T = 0 K), the value is nearly zero, and with increase in thermal vibration, the crystal may get deformed. Here \(<{\varDelta^{2} }>_{0} D\) shows deformation energy [43] which may arise due to the uncertainty of atomic positions (lattice mismatch).

4 Conclusion

In summary, the variation of band gap ‘Eg’ and Urbach energy ‘EU’ as a function of temperature has been extensively studied. From GGA + U calculations from PDOS, it is clear that the change in behavior of valence band maxima and conduction band minima is due to the overlapping of O-2p (VBM) with Ti-3d (CBM) orbitals, which can vary as disorder increases in sample. Dependency of Urbach energy and the slope of exponential tails (β1, β2) in density of states have also been studied. In the present investigation, diffuse reflectance spectroscopy used as tools to see the behavior of optical band gap with the influence of temperature and which helps to estimate the thermodynamic parameter like Debye temperature.

References

Tang H, Lévy F, Berger H, Schmid PE (1995) Urbach tail of anatase TiO2. Phys Rev B 52:7771–7774. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.52.7771

Thompson TL, Yates JT (2006) Surface science studies of the photoactivation of TiO2 new photochemical processes. Chem Rev 106:4428–4453. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr050172k

Di Valentin C, Pacchioni G, Selloni A (2009) Reduced and n-type doped TiO2: nature of Ti3+ species. J Phys Chem C 113:20543–20552. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp9061797

Mishra V, Sagdeo A, Kumar V et al (2017) Electronic and optical properties of BaTiO3 across tetragonal to cubic phase transition: an experimental and theoretical investigation. J Appl Phys 122:065105. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4997939

Mishra V, Warshi MK, Kumar R, Sagdeo PR (2018) Design and development of in situ temperature dependent diffuse reflectance spectroscopy setup. J Instrum 13:T11003. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-0221/13/11/T11003

Sagdeo A, Nagwanshi A, Pokhriyal P et al (2018) Disappearance of dielectric anomaly in spite of presence of structural phase transition in reduced BaTiO3: effect of defect states within the bandgap. J Appl Phys 123:161424. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5010870

Singh P, Choudhuri I, Rai HM et al (2016) Fe doped LaGaO3: good white light emitters. RSC Adv 6:100230–100238. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6RA21693E

Mishra V, Sati A, Warshi MK, Phatangare AB, Dhole S, Bhoraskar VN, Ghosh H, Sagdeo A, Mishra V, Kumar R, Sagdeo PR (2018) Effect of electron irradiation on the optical properties of SrTiO3: an experimental and theoretical investigations. Mater Res Express 5:036210

Mishra V, Warshi MK, Sati A et al (2018) Diffuse reflectance spectroscopy: an effective tool to probe the defect states in wide band gap semiconducting materials. Mater Sci Semicond Process 86:151–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mssp.2018.06.025

Kumar A, Warshi MK, Mishra V et al (2017) Strain control of Urbach energy in Cr-doped PrFeO3. Appl Phys A 123:576. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00339-017-1186-9

Cody GD, Tiedje T, Abeles B et al (1981) Disorder and the optical-absorption edge of hydrogenated amorphous silicon. Phys Rev Lett 47:1480–1483. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.47.1480

Zaynobidinov S, Ikramov RG, Jalalov RM (2011) Urbach energy and the tails of the density of states in amorphous semiconductors. J Appl Spectrosc 78:223–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10812-011-9450-9

Varshni YP (1967) Temperature dependence of the energy gap in semiconductors. Physica 34:149–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-8914(67)90062-6

Manoogian A, Woolley JC (1984) Temperature dependence of the energy gap in semiconductors. Can J Phys 62:285–287. https://doi.org/10.1139/p84-043

Kurik MV (1971) Urbach rule. Phys Status Solidi A 8:9–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/pssa.2210080102

Urbach F (1953) The long-wavelength edge of photographic sensitivity and of the electronic absorption of solids. Phys Rev 92:1324. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.92.1324

Martienssen W (1959) The optical absorption edge in ionic crystals. J Phys Chem Solids 8:294–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3697(59)90343-9

Abay B, Güder HS, Efeoğlu H, Yoğurtçu YK (2001) Temperature dependence of the optical energy gap and Urbach–Martienssen’s tail in the absorption spectra of the layered semiconductor Tl2GaInSe4. J Phys Chem Solids 62:747–752. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3697(00)00236-5

Rai HM, Saxena SK, Late R et al (2016) Observation of large dielectric permittivity and dielectric relaxation phenomenon in Mn-doped lanthanum gallate. RSC Adv 6:26621–26629. https://doi.org/10.1039/C5RA28074E

Rai HM, Saxena SK, Mishra V et al (2016) Observation of room temperature magnetodielectric effect in Mn-doped lanthanum gallate and study of its magnetic properties. J Mater Chem C 4:10876–10886. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6TC03641D

Rai HM, Saxena SK, Mishra V et al (2017) Importance of frequency dependent magnetoresistance measurements in analysing the intrinsicality of magnetodielectric effect: a case study. J Appl Phys 122:054103. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4997473

Kumar A, Warshi MK, Mishra V et al (2019) Optical spectroscopy: an effective tool to probe the origin of dielectric loss in Cr doped PrFeO3. Ceram Int. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.01.177

Blaha P, Schwarz K, Sorantin P, Trickey SB (1990) Full-potential, linearized augmented plane wave programs for crystalline systems. Comput Phys Commun 59:399–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-4655(90)90187-6

Blaha P, Schwarz K, Madsen G et al (2001) WIEN2K, an augmented plane wave + local orbitals program for calculating crystal properties. Karlheinz Schwarz, Technische Universität Wien, Wien

Warshi MK, Mishra V, Sagdeo A et al (2018) Structural, optical and electronic properties of RFeO3. Ceram Int 44:8344–8349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2018.02.023

Kohn W, Sham LJ (1965) Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys Rev 140:A1133–A1138. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.140.A1133

Hohenberg P, Kohn W (1964) Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys Rev 136:B864–B871. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.136.B864

Džimbeg-Malčić V, Barbarić-Mikočević Ž, Itrić K (2012) Kubelka–Munk theory in describing optical properties of paper (II). Tech Gaz 19:191–196

Kubelka P (1948) New contributions to the optics of intensely light-scattering materials. Part I. JOSA 38:448–457. https://doi.org/10.1364/JOSA.38.000448

Tauc J, Grigorovici R, Vancu A (2006) Optical properties and electronic structure of amorphous germanium. Phys Status Solidi B 15:627–637. https://doi.org/10.1002/pssb.19660150224

Wood DL, Tauc J (1972) Weak absorption tails in amorphous semiconductors. Phys Rev B 5:3144–3151. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.5.3144

Jiang LF, Shen WZ, Guo QX (2009) Temperature dependence of the optical properties of AlInN. J Appl Phys 106:013515. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3160299

Wu J, Walukiewicz W, Shan W et al (2003) Temperature dependence of the fundamental band gap of InN. J Appl Phys 94:4457–4460. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1605815

Pejova B, Abay B, Bineva I (2010) Temperature dependence of the band-gap energy and sub-band-gap absorption tails in strongly quantized ZnSe nanocrystals deposited as thin films. J Phys Chem C 114:15280–15291. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp102773z

Shojaee E, Mohammadizadeh MR (2010) First-principles elastic and thermal properties of TiO 2: a phonon approach. J Phys Condens Matter 22:015401. https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/22/1/015401

Fang J, Reitz C, Brezesinski T et al (2011) Thermal Conductivity of highly-ordered mesoporous titania thin films from 30 to 320 K. J Phys Chem C 115:14606–14614. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp203400t

Wasim SM, Rincón C, Marín G et al (2001) Effect of structural disorder on the Urbach energy in Cu ternaries. Phys Rev B 64:195101. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.64.195101

Chichibu S, Mizutani T, Shioda T et al (1997) Urbach–Martienssen tails in a wurtzite GaN epilayer. Appl Phys Lett 70:3440–3442. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.119196

Dow JD, Redfield D (1972) Toward a unified theory of Urbach’s rule and exponential absorption edges. Phys Rev B 5:594–610. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.5.594

Kranjčec M, Studenyak IP, Kurik MV (2006) Urbach rule and disordering processes in Cu6P(S1−xSex)5Br1−yIy superionic conductors. J Phys Chem Solids 67:807–817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpcs.2005.10.184

Kranjčec M, Studenyak IP, Bilanchuk VV et al (2004) Compositional behaviour of Urbach absorption edge and exciton–phonon interaction parameters in Cu6PS5I1−xBrx superionic mixed crystals. J Phys Chem Solids 65:1015–1020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpcs.2003.10.061

Zametin VI (1984) Absorption edge anomalies in polar semiconductors and dielectrics at phase transitions. Phys Status Solidi B 124:625–640. https://doi.org/10.1002/pssb.2221240222

Rakhshani AE (2000) Study of Urbach tail, bandgap energy and grain-boundary characteristics in CdS by modulated photocurrent spectroscopy. J Phys Condens Matter 12:4391. https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/12/19/309

Gafur G, Nosir Yusupjanovich S, Ulugbek Inoyatillaevich E (2013) The temperature dependence of the density of states in semiconductors. World J Condens Matter Phys. https://doi.org/10.4236/wjcmp.2013.34036

Kranjčec M, Studenyak IP, Kovacs GS et al (2001) Electric conductivity and optical absorption edge of Cu6P(SexS1−x)5I fast-ion conductors in the selenium-rich region. J Phys Chem Solids 62:665–672. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3697(00)00187-6

Orapunt F, O’Leary SK (2004) The Urbach focus and hydrogenated amorphous silicon. Appl Phys Lett 84:523–525. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1641176

Guerra JA, Montañez L, Zela FD et al (2013) On the origin of the Urbach rule and the Urbach focus. MRS Online Proc Libr Arch 1536:139–145. https://doi.org/10.1557/opl.2013.753

Allen PB, Cardona M (1981) Theory of the temperature dependence of the direct gap of germanium. Phys Rev B 23:1495–1505. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.23.1495

Banwell CN (1966) Fundamentals of molecular spectroscopy. McGraw-Hill, New York

Sathyanarayana DN (2015) Vibrational spectroscopy: theory and applications. New Age International, New Delhi

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank DST-FIST (SR/FST/PSI-225/2016) and SIC IIT Indore for providing some of the basic characterization facilities. Mr. Vikash Mishra, M. Kamal Warshi, and Mr. Anil Kumar sincerely thank Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD), Government of India, for providing financial support through teaching assistantship at IIT Indore. Ms. Aanchal Sati thanks CSIR New Delhi for providing junior research fellowship under Serial Number 1061651837.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mishra, V., Warshi, M.K., Sati, A. et al. Investigation of temperature-dependent optical properties of TiO2 using diffuse reflectance spectroscopy. SN Appl. Sci. 1, 241 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-0253-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-0253-6