Abstract

This paper explores the influence of the two historical and arguably most important correlates of fertility, i.e. female labor participation and pensions. We confirm the long-established negative impact of government provided pensions and all other welfare state social policies except pro-family ones on fertility between 1990 and 2013 in OECD countries. We also claim the reports about positive correlation between female labor participation and fertility, which caused a recent upsurge in research, to be spurious. Our results show a statistically insignificant relationship as a result of pro-family policies designed to offset the negative impact of female labor participation. We conclude that current societies in developed countries continue to have an unsustainable level of reproduction to an extent allowing depopulation, largely due to high and ever increasing female labor participation and a high level of social expenditure, particularly on pensions. We suggest an alternative set of pro-family and pro-natality policies and a decrease in social expenditure as a possible solution.

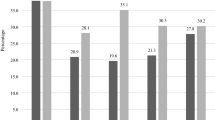

Source: World Bank and OECD databases

Source: World bank

Source: OECD

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The list of possible influences on TFR is obviously much longer. Guinnane (2011) gives a possible summary in his theoretical paper about the major economic explanations for fertility transition.

For a literature review of the rise and fall of fertility restrictions in early Europe please see Voigtländer and Voth (2012).

Note that this Figure displays social expenditure as a percentage of GDP. Our choice of this measure was motivated by the need to analyze social expenditure as an incentive or disincentive for having children, for which they need to be comparable across countries, especially in relation to the average wealth level in the country. The result of this choice is that part of the social expenditure development as visualized in Fig. 1, especially the peak in 2008 and subsequent significant drop, may be driven not so much by a change in social expenditure in absolute terms, but rather as a drop and then a recovery of GDP during the crisis and post-crisis period.

The number of years required for the population of an area to halve its size with current population growth, a mirror to doubling time.

For example, the Czech word “výminek” stems from the word “vymínit si”, or ‘to demand’, referring to the situation where the parent bequeaths the family inheritance usually to the oldest or strongest son in exchange for a separate room or an annex to the house, food rations and possibly rudimentary health care. The differences across cultures and countries, however, vary greatly from written contracts within extended family to the other extreme of no economic relationship between parents and children from the mid-teens, when children leave home (Guinnane 2011).

The number of children considered ideal by the general public is becoming a vital piece of sociological evidence. The reason for this is straightforward. In her description of the ageing Japanese society, Boling (2008) describes different types of personal gratification before marriage which lead to its postponement and late childbearing in order to conclude: “Perhaps the self-fulfilling quality of such decisions and values is leading Japan into a “fertility trap” as theorized by Lutz et al. (2006), which seems already to have changed the ideal number of children in Germany from 2.0 to 1.76” (Boling 2008, p. 321). Let us note that Germany has real TFR below 1.76 and is depopulating by about 200,000 people every year with negative prospects.

Eurobarometer survey (2008), family life and the needs of an aging population, summary.

These countries are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, United Kingdom and United States.

More precisely, only one variable, the wage gap between sexes, is available since 2000 only. However, from a theoretical point of view (and based on our empirical findings as well), it is a crucial variable in the model.

Note that favourable conditions for women on the labor market should not be restricted only to employed women and that self-employment (entrepreneurship) is often a way how mothers reconcile their professional and family life. As Zwan et al. (2016), women engage in “necessity entrepreneurship” significantly more often than men.

Note also that the relationship between social expenditure and family can get even more complex when inter-family altruism is taken into account, as shown by Koda and Uruyos (2015).

To further support this conjecture, we performed auxiliary regressions confirming that social expenditure on family (containing expenditure on maternity and parental leave) are positively correlated with female labor force participation and negatively correlated with unemployment.

A financial tool reportedly tested in Estonia. The amount is linked to the mother's previous wages.

References

Adserà, A. (2004). Changing fertility rates in developed countries. The impact of labour market institutions. Journal of Population Econ, 17(1), 17–43.

Adserà, A. (2005) Vanishing children: From high unemployment to low fertility in developed countries. The American Economic Review, 95(2), Paper and proceedings of the one hundred seventeenth annual meeting of the American Economic Association, Philadelphia, PA, 189–193.

Barro, J. R. (1974). Are government bonds net wealth? The Journal of Political Economy, 82(6), 1095–1117.

Becker, G. S. (1960) An economic analysis of fertility. In: Universities-National Bureau, Demographic and economic change in developed countries, 209–240.

Boldrin, M. and De Nardi, M. & Jones, L. E. (2005) Fertility and social security. NBER Working Paper No. 11146.

Boling, P. (2008). Demography, culture, and policy: Understanding Japan’s low fertility. Population and Development Review, 34(2), 307–326.

Bongaarts, J. (1978). A framework for analyzing the proximate determinants of fertility. Population and Development Review, 4(1), 105–132.

Bongaarts, J., Cleland, J., Townsend, J. W., Bertrand, J. T., Das Gupta, M. (2012). Family planning programs for the 21st century: Rationale and design. The Population Council.

Bongaarts, J., & Sobotka, T. (2012). A demographic explanation for the recent rise in European fertility. Population and Development Review, 38(1), 83–120.

Butz, W. P., & Ward, M. P. (1979). Countercyclical U.S. fertility and its implications. Social Security Bulletin, 42(8), 38–43.

Chesnais, J.-C. (1996). Fertility, family, and social policy in contemporary Western Europe. Population and Development Review, 22(4), 729–739.

D’Ercole, M. M. & D’Addio, A. C. (2005). Trends and determinants of fertility rates in OECD countries: The role of policies. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers.

Da Rocha, J. S., & Fuster, L. (2006). Why are fertility rates and female employment ratios positively correlated across OECD countries? International Economic Review, 47(4), 1187–1222.

De Jager, A. (2013). Social welfare policy as an instrument for fertility regulation. Netspar Theses.

Doepke, M., Hazan, M. & Maoz, Y. (2015). The baby boom and World War II: A macroeconomic analysis. NBER Working Paper No. 13707.

Easterlin, R. A. (1973). Does money buy happiness? The Public Interest, 30, 3–10.

Easterlin, R. A. (1980). Birth and fortune: The impact of numbers on personal welfare. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Entwise, B., & Winegarden, C. R. (1984). Fertility and pension programs in LDCs: A model of mutual reinforcement. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 32(2), 331–354.

European Commission (2008) Family life and the needs of an aging population: Summary. Flash Eurobarometer 247.

Evan, T. (2014). Chapters of European economic history. Prague: Karolinum Press.

Fenge, R. & Scheubel, B. (2013). Pensions and fertility: Back to the roots. The introduction of Bismarck’s pension scheme and the European fertility decline. CESifo Working Paper No. 4383.

Glowaki, T., & Richmond, A. K. (2007). How government policies influence declining fertility rates in developed countries. Middle States Geographer, 40, 32–38.

Goldstein, J., Sobotka, T., & Jasilioniene, A. (2009). The end of “Lowest-Low” fertility? Population and Development Review, 35(4), 663–699.

Golini, A. (1998). How low can fertility be? An empirical exploration. Population and Development Review, 24(1), 59–73.

Guinnane, T. W. (2011). The historical fertility transition: A guide for economists. Journal of Economic Literature, 49(3), 589–614.

Hajnal, J. (1965). European marriage patterns in perspective. In D. V. Glass & D. E. Eversley (Eds.), Population in history: Essays in historical demography (pp. 101–143). Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company.

Hohm, C. F. (1975). Social security and fertility: An international perspective. Demography, 12(4), 629–644.

Hyatt, D. E., & Milne, W. J. (1991). Can public policy affect fertility? Canadian Public Policy, 17(1), 77–85.

Kalwij, A. (2010). The impact of family policy expenditure on fertility in Western Europe. Demography, 47(2), 503–519.

Koda, Y., & Uruyos, M. (2015). Altruism and four shades of family relationships. Eurasian Economic Review, 5(2), 345–365.

Kögel, T. (2004). Did the association between fertility and female employment within OECD countries really change its sign? Journal of Population Economics, 17(1), 45–65.

Kohler, H.-P., Billari, F. C., & Ortega, J. A. (2002). The emergence of lowest-low fertility in Europe during the 1990s. Population and Development Review, 28(4), 641–680.

Lee, R. (2003). The demographic transition: Three centuries of fundamental change. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17(4), 167–190.

Liebenstein, H. (1957). Economic backwardness and economic growth. Hoboken: Wiley.

Livingstone, G. (2014). Birth rates lag in Europe and the U.S., but the desire for kids does not. Washington DC: Pew Research Center.

Lutz, W., Skirbekk, V. and Testa, M.R. (2006). The low-fertility trap hypothesis: forces that may lead to further postponement and fewer births in europe. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, Vol. 4, Postponement of Childbearing in Europe, pp. 167–192.

Macunovich, D. J. (1998). Relative cohort size and inequality in the United States. American Economic Review, 88(2), 259–264.

McDonald, P. (2007). Low fertility and policy. Ageing Horizons, 7, 22–27.

Michel, P., & Cardia, E. (2004). Altruism, intergenerational transfers of time and bequests. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 28(8), 1681–1701.

Morgan, P. S. (2003). Is low fertility a twenty-first-century demographic crisis? Demography, 40(4), 589–603.

Örsal, D. D. K. & Goldstein, J. R. (2010). The increasing importance of economic conditions on fertility. MPIDR Working Paper WP 2010-014.

Pampel, F. C. (1993). Relative cohort size and fertility: The socio-political context of the Easterlin effect. American Sociological Review, 58(4), 496–514.

Rank, M. R. (1989). Fertility among women of welfare: Incidence and determinants. American Sociological Review, 54(2), 296–304.

Testa, M. R. (2011). Family sizes in Europe: Evidence from the 2011 Eurobarometer survey. European Demographic Research Papers. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Maria_Testa/publication/263051049_Family_Sizes_in_Europe_Evidence_from_the_2011_Eurobarometer_Survey_Contents/links/0c960539aac38d1098000000.pdf. Accessed 5 Jul 2016.

United Nations (2015). World population prospects: The 2015 revision. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs/Population Division.

Van der Zwan, P., Thurik, R., Verheul, I., & Hessels, J. (2016). Factors influencing the entrepreneurial engagement of opportunity and necessity entrepreneurs. Eurasian Business Review, 6(3), 273–295.

Voigtländer, N. & Voth, H.-J. (2012). How the west ‘invented’ fertility restriction. NBER Working Paper No. 17314.

Walker, J. R (1995). The effect of public policies on recent Swedish fertility behavior. Journal of Population Economics, 8(3), 223–251.

Willis, R. J. (1973). A new approach to the economic theory of fertility behavior. Journal of Political Economy, 81(2), S14–S64.

Wright, R. E. (1989). The Easterlin hypothesis and European fertility rates. Population and Development Review, 15(1), 107–122.

Yang, J. (2013). Parochial welfare politics and the small: Welfare state in South Korea. Comparative Politics, 45(4), 457–475.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Evan, T., Vozárová, P. Influence of women’s workforce participation and pensions on total fertility rate: a theoretical and econometric study. Eurasian Econ Rev 8, 51–72 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40822-017-0074-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40822-017-0074-0