Abstract

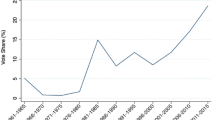

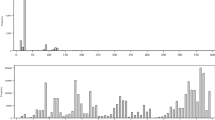

The strategic manipulation of fiscal policy in the context of winning elections is a hotly debated issue in economics and political economy. This paper is a theoretical analysis of the manipulation of fiscal policy by an electorally motivated incumbent politician who derives utility from voting support and dis-utility from primary deficit. The incumbent could be one of the following two types: opportunistic or partisan. Using the method of optimal control, the paper derives the equilibrium time paths of both voting support and primary deficit by the incumbent in a dynamic model of finite time horizon under complete information. The level of voting support obtained in case of both types of incumbents is found to be positive and rising over time. Thus, the opportunistic and partisan budgetary cycles follow a similar time pattern, although the cyclicality in case of former is more pronounced than in case of latter in the period closer to the election year. Besides, an opportunistic incumbent is more likely to face rejection when there is sufficiently strong anti-incumbency. Thus, in case of anti-incumbency with opportunism, primary deficit and voting support fall over time. An opportunistic incumbent is also likely to find it costlier to run a primary deficit higher than a specified threshold level than a partisan one. This implies that per unit votes garnered by raising the primary deficit in excess of the threshold level are lower when the incumbent is opportunistic than when she/he is partisan. Numerical simulations corroborate these analytical results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

04 March 2019

The original version of this article contained the Appendix. The Appendix has been removed and published online as electronic supplementary material.

Notes

In fact, ‘some’, deficit in the economy is claimed to be good if an economy is spending on productive investment activities. However, a large magnitude of expenditure today entails higher future tax, which voters might not like and, hence, expenditure has to be contained below a certain threshold level. In India, for instance, it has been decided to maintain the aggregate fiscal deficit at 3% of gross domestic product (GDP) under the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act (FRBM Act-2003).

While the FRBM Act was passed in 2003, it started having an impact only a few years later.

The analysis in this paper refers to the primary deficit throughout, where positive and negative values represent primary surplus and primary deficit respectively.

The national level elections refer to either parliamentary or presidential elections depending on whether the country follows a parliamentary or presidential form of government.

This is the time path of the fiscal policy variable (and the associated voting support) that maximizes the pay-off for the incumbent government over an election cycle.

It is stated that, “one candidate may be particularly able (or unable) to cope with a shock in the price of oil, or to enact the effective labor market legislation, or to negotiate with trade unions (Persson and Tabellini 1990. pp. 80).”

The opportunistic behavior of different partisan politicians may be different. Adjusting the party’s standing position toward the ‘middle’ might be the most effective opportunistic policy for a partisan politician.

Visible good refers to public provision of the good that is perceived to provide direct or visible benefits to the citizen-voter—for example, providing solar panels as a public good provision.

Note that, as more and more voting support is rendered to the incumbent, there will be more withdrawal (friction) of the citizen-voters over the electoral term, which may also be due to the presence of an alternative party in the political arena. It is this parameter of friction that captures the notion of anti-incumbency later in the analysis.

From eq. (18), the part of the last term \( e^{{ - \frac{\rho }{\epsilon }t + \frac{\alpha - \delta \gamma }{\delta \epsilon }(t - T)}} \) can be written as \( e^{{ - \frac{\rho }{\epsilon }t}} .e^{{\frac{\alpha - \delta \gamma }{\delta \epsilon }(t - T)}} \) where, as \( t \to T \) and small enough \( \epsilon \), we have \( e^{{ - \frac{\rho }{\epsilon }t}} \to 0 \) and \( {{ \frac{\alpha - \delta \gamma }{\delta \epsilon }(t - T)}}\to 1 \).

While no explicit thresholds on parameters are required, suffice is to say that the regularity condition in Eq. (16) is met.

References

Aidt TS, Veiga FJ, Veiga LG (2011) Election results and opportunistic policies: a new test of the rational political business cycle model. Public Choice 148(1):21–44

Alesina A (1987) Macroeconomic policy in a two-party system as a repeated game. Q J Econ 102(3):651–678

Alesina A (1988) Macroeconomics and politics. NBER Macroecon Ann 3:13–52

Alesina A, Perotti R (1995a) Fiscal expansions and adjustments in OECD countries. Econ Policy 10(21):205–248

Alesina A, Perotti R (1995b) The political economy of budget deficits. Staff Papers 42(1):1–31

Alesina A, Rosenthal H (1995) Partisan politics, divided government, and the economy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Alesina A, Sachs J (1988) Political parties and the business cycle in the United States, 1948–1984. J Money Credit Bank 20(1):63–82

Alesina A, Cohen GD, Roubini N (1993) Electoral business cycle in industrial democracies. Eur J Polit Econ 9(1):1–23

Block SA (2002) Political business cycles, democratization, and economic reform: the case of Africa. J Dev Econ 67(1):205–228

Brender A, Drazen A (2005) Political budget cycles in new versus established democracies. J Monet Econ 52(7):1271–1295

Brender A, Drazen A (2013) Elections, leaders, and the composition of government spending. J Pub Econ 97:18–31

Cafiso G (2012a) Debt developments and fiscal adjustment in the EU. Intereconomics 47(1):61–72

Cafiso G (2012b) A guide to public debt equations. SSRN Working Paper

Chiang A (1992) Elements of dynamic optimization. McGraw-Hill, New York

Chortareas G, Logothetis V, Papandreou AA (2016) Political budget cycles and reelection prospects in greece’s municipalities. Eur J Polit Econ 43:1–13

Cukierman A, Meltzer AH (1986) A positive theory of discretionary policy, the cost of democratic government and the benefits of a constitution. Econ Inq 24(3):367–388

Drazen A (2000) The political business cycle after 25 years. NBER Macroecon Ann 15:75–117

Drazen A, Eslava M (2010) Electoral manipulation via voter-friendly spending: theory and evidence. J Dev Econ 92(1):39–52

Election Guide (2018) Year of election. http://www.electionguide.org/elections/past/. Accessed 27 June 2018

Fair RC (1978) The effect of economic events on votes for president. Rev Econ Stat 60(2):159–173

Frey BS, Schneider F (1978) An Empirical study of politico–economic interaction in the United States. Rev Econ Stat 65(01):174–183

Hibbs DA (1977) Political parties and macroeconomic policy. Am Polit Sci Rev 71(04):1467–1487

Hibbs DA (1989) The American political economy. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Kalecki M (1943) Political aspects of full employment. Polit Q 14(4):322–330

Klomp J, De Haan J (2013a) Do political budget cycles really exist? Appl Econ 45(3):329–341

Klomp J, De Haan J (2013b) Political budget cycles and election outcomes. Pub Choice 157(1–2):245–267

Kramer GH (1971) Short-term fluctuations in US voting behavior, 1896–1964. Am Polit Sci Rev 65(01):131–143

Lindbeck A (1976) Stabilization policy in open economies with endogenous politicians. Am Econ Rev 66(2):1–19

IMF Fiscal Monitor-2017 (2018) Primary surplus or deficit. https://www.imf.org/~/media/Files/Publications/fiscal-monitor/2017/October/data/FiscalMonitorDatabaseOct2017.ashx. Accessed 25 June 2018

Nordhaus WD (1975) The political business cycle. Rev Econ Stud 42(2):169–190

Persson T, Tabellini GE (1990) Macroeconomic policy, credibility and politics. Taylor and Francis, London

Persson T, Tabellini GE (2002) Political economics: explaining economic policy. The MIT Press, Cambridge

Rogoff K (1990) Equilibrium political budget cycles. Am Econ Rev 80(1):21–36

Rogoff K, Sibert A (1988) Elections and macroeconomic policy cycles. Rev Econ Stud 55(1):1–16

Schuknecht L (1996) Political business cycles and fiscal policies in developing countries. Kyklos 49(2):155–170

Shi M, Svensson J (2006) Political budget cycles: do they differ across countries and why? J Pub Econ 90(8):1367–1389

Tufte ER (1975) Determinants of the outcomes of mid-term congressional elections. Am Polit Sci Rev 69(03):812–826

Westen D (2008) The political brain: the role of emotion in deciding the fate of the nation. PublicAffairs, New York

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants at the IGC-ISI Summer School Workshop July 12–16, 2014, the Winter School, December 5–17, 2014 at the Delhi of School of Economics, University of Delhi and the conference on ‘Papers in Public Economics and Policy’ at National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP), New Delhi, on March 12–13, 2015. We also benefitted by comments from Prof. Chetan Ghate and Prof. Dilip Mookherjee at the IGC-ISI workshop and Dr. Mausumi Das at the Winter School. We are grateful to Dr. Bodhisattva Sengupta and two anonymous referees for their insightful and valuable comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Manjhi, G., Mehra, M.K. Dynamics of Political Budget Cycle. Ital Econ J 5, 135–158 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-019-00084-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-019-00084-1

Keywords

- Opportunistic incumbent

- Partisan incumbent

- Primary deficit

- Voting support

- Political budget cycles

- Anti-incumbency