Abstract

Using both macro and firm-level data, we provide an in-depth analysis of Italy’s goods exports relative to its three main trading partners (Germany, France and Spain) in order to gauge the causes of its relative underperformance prior to the 2008–2009 crisis and to assess whether the improvement observed since 2010 reflects cyclical or structural factors. We argue that Italy’s relatively unsatisfactory performance in the 2000s was the result of the interplay between the appreciation of its real effective exchange rate, its specialization in products that were particularly exposed to increasing competition from China, and the size distribution of its exporters, skewed towards small firms. In recent years signs of structural improvement have emerged, alongside cyclical factors, in connection with a shift in the specialization of exports towards sectors that are less exposed to competitive pressures; moreover, the selection process triggered by the exceptional difficulties encountered by micro and small firms both before and during the global financial crisis have plausibly strengthened the population of Italian exporters, making it structurally more resilient to exchange rate appreciations and more capable of keeping pace with external demand developments.

Source: Authors’ calculations on Eurostat and national sources’ (IMTS) data. Percentage contributions to the annual export growth differential between Italy and the other main euro-area countries. (1) “other 3” is the difference between the contribution to the growth rate of Italian exports of sales in the remaining three countries on the one hand, and the contribution to the growth rate of country j’s exports (j representing France, Germany or Spain) of sales in the remaining three countries on the other hand

Source: Authors’ calculations on Istat, Eurostat and IMF-WEO data. (1) Share of Italian goods’ exports on total goods’ imports (at current prices) by reference area (excluding Italy, when applicable)

Source: Authors’ calculations on Eurostat and national sources’ (IMTS) data. Data at the 2-digit level of the Harmonized System classification have been re-arranged so as to mimic the CPA classification. Data for France in 1999 are estimated. (1) For France this category includes goods that are not allocated to any other sector

Source: Authors’ calculations on ICE-Istat IMTS data. Exports for which the exporters’ size was not available are omitted. In panel b) on the horizontal axis percentage changes are reported

Source: Authors’ calculations on Istat and IMF-WEO data

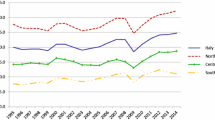

Source: Authors’ calculations on national sources, Eurostat and IMF-WEO data. (1) The indicator considers the import volumes of the main 80 trading partners of each country (covering about 98–99 per cent of its exports and sourced from national accounts data at constant prices from the IMF WEO) and weights them with their average share in the country’s exports in 1999–2000 (for the indicator from 1999 to 2007) and in 2006–2007 (for the indicator from 2008 onwards)

Source: Banca d’Italia. (1) The real effective exchange rate is deflated by producer prices of manufactures sold domestically (see Felettigh et al. 2016 for details on the methodology). An increase in the indicator signals a loss in price competitiveness. (2) Ratio of country’s producer prices to partners’ prices

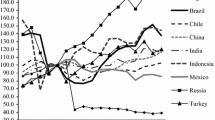

Source: Authors’ calculations on CEPII-BACI data

Source: Authors’ calculations on CEPII-BACI data. (1) Exports at current prices. Mineral and energy products are excluded

Source: Authors’ calculations on CEPII-BACI data. The graph aggregates quality estimates at the product level up to the origin–destination-year level using fixed products weights

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The database, illustrated in Timmer et al. (2016), covers 43 countries over the period 2000–2014.

Felettigh and Oddo (2016) find that market shares based on gross exports are generally consistent with market shares based on value added, especially for advanced economies, although the export performance of Germany relative to France and Italy is less outstanding in value-added terms.

Exports of motor vehicles account for almost 20 per cent of German exports, against less than 10 per cent in Italy.

On the changes in the population of exporters based on firm-level data see Bugamelli et al. (2018).

The measure considers 80 destination countries, whose import volumes are taken from the IMF-WEO database, and whose weight for year t is based on the corresponding weight on Italian exports at current prices in the triennium t − 3, t − 2, t − 1 (rolling base). Rolling 3-year periods, in the place of more volatile previous-period weights, are a good compromise for capturing the stickiness of a country’s export specialization. Moreover, they also help capturing more gradually the “transition between steady states” that began, for example, after China joined the WTO.

A similar indicator of external demand for Italian exports, constructed on the basis of trade flows at current prices at the country-product level sourced from CEPII-BACI—a dataset that provides symmetrized trade flows among around 220 countries for more than 5000 products (HS 6-digit classification), for a total of about 1.1 million potential destination markets—indicates that whereas before the crisis Italy’s exports lagged behind demand in all sectors except for electronics, after 2010 they succeeded in increasing at similar rates in the machinery, food and leather sectors and even outpaced potential demand in the pharmaceutical and motor vehicles industries.

Banca d’Italia produces monthly price-competitiveness indicators, deflated by producer prices of manufactures sold domestically, for 62 countries (see Felettigh et al. 2016).

Although theoretically and empirically no deflator proves to be optimal, it is noteworthy that different trends emerge when considering indicators based on alternative deflators, such as consumer prices, GDP deflators and unit labour costs (Turner and Van’t Dack 1993; Chinn 2006; Giordano and Zollino 2016).

This component can be further decomposed into three items, which separately capture the sectoral and the geographical specialization as well as their interaction.

Another significant development was the trade integration of Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries, which led to “regional supply chains” and which might have displaced Italian exports, especially those to the German market. The magnitude of this shock was however considerably smaller: while China’s market share on world trade increased by 10 percentage points between 1999 and 2015, the combined market share of the main five CEE countries (the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia) increased by just 1.6 percentage points in the same period. We therefore choose to focus only on competition from China in this part of our analysis, although we are aware that competition from CEE countries might have been a factor behind Italy's less favourable performance on euro-area markets.

We consider more than 4500 products at the HS 6-digit level, excluding mineral products to avoid that results be influenced by commodity price cycles, as exports are measured at current prices. Similar results emerge if we measure intensity of competition from China using its market share in 2015.

In other words, we assume that the share of high-competition products in Italian exports in 1999 was not 31 but 21 per cent, that those of the medium and low-competition product groups were proportionately larger (41 and 38 per cent, respectively, instead of 36 and 33), and that the percentage decline in each segment’s share on world trade was the same as that observed.

In a less conservative counterfactual scenario, where we assume that Italy’s shares of medium and high-competition products are also in line with the average of the other three euro-area countries (27 and 52 per cent of total exports, respectively, in 1999), the loss of Italy’s share on world trade would have been about 3.5 percentage points smaller. The growth gap with respect to Germany and Spain would now be reduced by almost 25 per cent.

A second word of caution is that this methodology infers quality only from the demand side; that is, differences in the cost structure across exporting countries are not considered. However, since higher prices due to higher costs negatively affect quantities, by focusing on demand shifters our methodology does not misattribute those differences to (higher) quality. Finally, the methodology rests on a constant-elasticity-of-substitution demand system, and hence disregards potential price variation across firms due to differences in mark-ups.

Results of robustness exercises based on alternative weighting schemes, rather than US imports, are qualitatively similar.

When the export quality indicator is regressed on GDP per capita, controlling for different sets of fixed effects, the R2 is around 0.4, the coefficient of GDP per capita is positive and statistically significant and its magnitude is significantly higher for Germany and Italy than for France and Spain.

We compute for each product-origin–destination the yearly percentage change in our estimated quality parameter. For each country we then exclude observations below the 5th and above the 95th percentile to reduce the influence of outliers.

The average level of quality masks significant heterogeneity across sectors. In comparison with Germany, Italian products are characterized by a relatively high quality in footwear, textiles and other non-metallic mineral products. Relative quality in these sectors also shows an upward trend, supporting the hypothesis that Italian exporters of “traditional” products, exposed to price-based competitive pressures from low-wage economies, have reacted by raising the quality of their exports.

All results reported in this section are broadly robust to clustering standard errors by country-sector. The results and the robustness tests not reported here are available upon request.

Italy’s exports also turn out to be more sensitive to price-competitiveness developments than in the other countries when alternatively deflated REERs are employed (see Bugamelli et al. 2017).

When the share of small firms is included in the baseline regression with only the two standard determinants and no sector and year fixed effects, it is marginally significant and with the expected negative sign.

See Gaulier and Zignago (2010) for the methodological details of the CEPII-BACI dataset.

The NACE Rev.1.1 classification disaggregates manufacturing into 14 branches. We drop “Coke, Refined Petroleum and Nuclear Fuel” due to the fact that it is a clear outlier at current prices and “Manufacturing, Nec; Recycling”, for which REER data are unavailable.

Data are available at: http://www.rieti.go.jp/users/eeri/en/. This variable is available for the 2007 NACE Rev.2 classification: similarly to other variables broken down according to this classification, in order to obtain the Nace Rev.1.1 disaggregation, which is less disaggregated, weighted averages of the sectoral variables were taken, where the weights were given by the country-specific time-varying value added shares, computed on Eurostat data, of each NACE Rev.2 sector in the more aggregated NACE Rev.1.1 sector.

References

Amici M, Bobbio E, Torrini R (2017) Patterns of convergence (divergence) in the euro-area. Profitability versus cost and price indicators. Banca d’Italia Occasional Papers, No. 415

Amiti M, Itskhoki O, Konings J (2014) Importers, exporters, and exchange rate disconnect. Am Econ Rev 104(7):1942–1978

Anderson JE, van Wincoop E (2003) Gravity with gravitas: a solution to the border puzzle. Am Econ Rev 93(1):170–192

Autor DH, Dorn D, Hanson GH (2016) The China Shock: learning from labor market adjustment to large changes in trade. Ann Rev Econ 8(1):205–240

Barba Navaretti G, Bugamelli M, Forlani E, Ottaviano GIP (2017) It takes (more than) a moment: revisiting the link between firm productivity and aggregate exports. Mimeo

Bayoumi RT, Harmsen J, Turunen T (2011) Euro area export performance and competitiveness. IMF Working Papers, No. 140

Berman N, Martin P, Mayer T (2012) How do different exporters react to exchange rate changes? Q J Econ 127(1):437–492

Bernard AB, Eaton J, Jensen JB, Kortum S (2003) Plants and productivity in international trade. Am Econ Rev 93(4):1268–1290

Bernard AB, Jensen JB, Schott PK (2006a) Survival of the best fit: exposure to low wage countries and the (Uneven) growth of US manufacturing plants. J Int Econ 68:219–237

Bernard AB, Jensen JB, Schott PK (2006b) Trade costs, firms and productivity. J Monetary Econ 53:917–937

Berthou A, Dyhne E (2018) Exchange rate movements, firm-level exports and heterogeneity. Banque de France Working Papers, No. 660

Berthou A, Dhyne E, Bugamelli M, Cazacu AM, Demain CV, Harasztosi P, Lalinsky T, Merikull J, Oropallo F, Soares AC (2015) Assessing European firms’exports and productivity distributions: the CompNet trade module. ECB Working Papers, No. 1788

Bloom N, Draca M, Van Reenen J (2015) Trade induced technical change: the impact of Chinese imports on innovation, diffusion and productivity. Review of Economic Studies 83(1):87–117

Bricogne J-C, Fontagné L, Gaulier G, Taglioni D, Vicard V (2012) Firms and the global crisis: French exports in the turmoil. J Int Econ 87(1):134–146

Broda C, Weinstein DE (2006) Globalization and the gains from variety. Q J Econ 121(2):541–585

Bugamelli M, Lotti F (eds), Amici M, Ciapanna E, Colonna F, D’Amuri F, Giacomelli S, Linarello A, Manaresi F, Palumbo G, Scoccianti F, Sette E (2018) Productivity growth in Italy: a tale of a slow-motion change. Banca d’Italia Occasional Papers, No. 422

Bugamelli M, Rosolia A (2006) Produttività e concorrenza estera. Riv di Politica Econ 96(5):55–88

Bugamelli M, Schivardi F, Zizza R (2009) The euro and firm restructuring. In: Alesina A, Giavazzi F (eds) Europe and the Euro. Chicago University Press, Chicago

Bugamelli M, Fabiani S, Sette E (2015a) The age of the dragon: the effect of imports from China on firm-level prices. J Money Credit Bank 47(6):1091–1118

Bugamelli M, Gaiotti E, Viviano E (2015b) Domestic and foreign sales: complements or substitutes? Econ Lett 135:46–51

Bugamelli M, Fabiani S, Federico S, Felettigh A, Giordano C, Linarello A (2017) Back on track? A macro-micro narrative of italian exports. Banca d’Italia Occasional Papers, No. 399

Bugamelli M, Linarello A, Serafini R (2018) The ‘Margin Call’: firm-level export dynamics in Italy. Banca d’Italia, Mimeo

Campa JM, Goldberg LS (2005) Exchange rate pass-through into import prices. Rev Econ Stat 87(4):679–690

Chinn MD (2006) A primer on real effective exchange rates: determinants, overvaluation, trade flows and competitive devaluation. Open Econ Rev 17:115–143

De Bonis R, Ferri G, Rotondi Z (2015) Do firm-bank relationships affect firms’ internationalization? Int Econ 142:60–80

Del Prete S, Federico S (2014) Trade and finance: is there more than just “trade finance”?” Banca d’Italia Working Papers, No. 948

Di Mauro F, Forster K (2008) Globalisation and the competitiveness of the Euro Area. ECB Occasional Papers, No. 97

Federico S (2014) Industry dynamics and competition from low-wage countries: evidence on Italy. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 76(3):389–410

Felettigh A, Oddo G (2016) Market shares in manufacturing value-added: is the picture different? Banca d’Italia Occasional Papers, No. 336

Felettigh A, Giordano C, Oddo G, Romano V (2016) New indicators to assess price-competitiveness developments in the four largest euro-area countries and in their main trading partners. J Econ Soc Meas 41(3):203–235

Gaulier G, Zignago S (2010) BACI: International Trade Database at the Product-level: The 1994–2007 version. CEPII Document du Travail 2010–23

Giordano C, Zollino F (2016) Shedding light on price- and non-price competitiveness determinants of foreign trade in the four largest euro-area countries. Rev Int Econ 24(3):604–634

Giordano C, Toniolo G, Zollino F (2017) Long run trends in Italian productivity. Banca d’Italia Occasional Papers, No. 406

Giovannetti G, Sanfilippo M (2016) China’s competition and the export price strategies of developed countries. Int Rev Appl Econ 30(2):238–254

Giovannetti G, Sanfilippo M, Velucchi M (2011) The “China effect” on EU Exports to OECD markets—a focus on Italy. Universita’ degli Studi di Firenze Economics Working Papers, No. 17

Goldstein M, Kahn MS (1985) Income and price effects in foreign trade. In: Jones RW, Kenen PB (eds) Handbook of International Economics, vol 2. North Holland, Amsterdam

Khandelwal AK, Schott PK, Wei S-J (2013) Trade liberalization and embedded institutional reform: evidence from Chinese exporters. Am Econ Rev 103(6):2169–2195

Koopman R, Wang Z, Wei S-J (2014) Tracing value-added and double counting in gross exports. Am Econ Rev 104(2):459–494

Linder SB (1961) An essay in trade and trasformation. Stockholm, Almqvist and Wiksell

Mayer T, Ottaviano GIP (2011) The happy few: the internationalization of European firms. Blueprints Bruegel, p 12

Melitz MJ (2003) The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica 71:1695–1725

Muir DV, Elekdag S (2013) Trade linkages, balance sheets and spillovers: the Germany-Cental European Supply Chain. IMF Working Papers, No. 210

Sato K, Shimizu J, Shrestha N, Zhang S (2015) Industry-specific real effective exchange rates in Asia. RIETI Discussion Papers 15-E-036

Soderbery A (2015) Estimating import supply and demand elasticities: analysis and implications. J Int Econ 96(1):1–17

Timmer MP, Los B, Stehrer R, de Vries GJ (2016) An anatomy of the global trade slowdown based on the WIOD 2016 Release. GGDC Research Memorandum, No. 162

Turner P, Van’t dack J (1993) Measuring international price and cost competitiveness. BIS Economic Papers, No. 39

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Details on the Datasets Underlying the Empirical Analysis

Appendix: Details on the Datasets Underlying the Empirical Analysis

1.1 Country-Sector Regressions

Exports (exp) Exports of goods at current prices are taken from the CEPII-BACI database.Footnote 24 We use the 1996 version of the 6-digit HS classification, which we aggregate up into 12 manufacturing branches defined by the 2002 Nace Rev.1.1 classification.Footnote 25 Exports of goods data are converted from US dollars into euros using the average annual nominal bilateral exchange rate.

Real Effective Exchange Rate (REER) It is the sector-level REER produced by Sato et al. (2015).Footnote 26 Similarly to the Bank of Italy’s total manufacturing REER, this indicator is deflated using PPIs; however, it is constructed vis-à-vis 28 trading partners (against 61 for the Banca d’Italia indicator).

Potential Demand (potdem) It is constructed using CEPII-BACI data for each country-sector-year cell and is based on three different sets of import weights: (a) average 1998–2000 weights; (b) average 2005–2007 weights and (c) a series obtained by splicing the previous two. We chose to fix the weights at the beginning of the period considered (case a) or at its midpoint (case b), as opposed to rolling-base alternatives, in order to reduce a potential reverse causality bias between export and potential demand developments. Results shown in the paper are based on series (c), although findings are confirmed (and available upon request) when (a) or (b) are used.

Competition From China (comp China) It is proxied by the share of Chinese exports to all destinations in world trade for each sector-year constructed on CEPII-BACI data; it is the same across all four main euro-area countries.

Product Quality (quality) It is based on the measure discussed in Sect. 4.2, employing the elasticities of substitution estimated by Soderbery (2015) and aggregating up to the NACE Rev.1.1 sectoral level using country-specific weights (given by the country average over the entire period). Alternative indicators use the elasticities of substitution taken from Broda and Weinstein (2006) and different sets of weights; results, available upon request, are robust to these alternative indicators.

Firm Size (share 0–49) We exploit Eurostat’s Structural Business Statistics database, which provides information on the number of total manufacturing firms in different size classes by country, and assume that the size composition of all firms is similar to that of exporters. Owing to the patchiness of the data, we select a year for which missing values are few and which represents a mid-point in the period under analysis, namely 2005. We define “small” firms as those with 0–49 employees, but results, available upon request, are robust also to 0–9 and 0–19 size classes.

Capacity Utilization (caputil) This indicator is based on the monthly European Commission Business Survey of manufacturing firms. It is the average current level of capacity utilization in percentage points reported by firms within each country-sector.

Financial Constraints (finconstr) We extract the share of manufacturing firms which report that financial factors are an obstacle to their economic activity from the above-mentioned European Commission Business Survey. We then define a dummy taking value 1 if the share is above the 90th percentile of the distribution of this variable across the four main euro-area countries, 0 otherwise.

1.2 Firm-Level Regressions

Exports (exp) Based on Istat data on the universe of Italian exporters, the dataset on firm-level exports of goods at current prices refers to the firms that provide information on the breakdown of foreign sales by product; these are, according to statistical reporting requirements, all firms that annually export more than 250,000 euros to EU markets and more than 1000 euros to extra-EU countries.

Potential Demand (Δpotdem) Potential demand growth rates at the firm-level are constructed as follows. First, we define the firm-specific mix of exported products (p) at the HS 6-digit level to destination market (d), as that observed in the first year (t = 0) the firm enters the sample. Second, for any product-destination mix (p,d) we compute the growth rate of country d’s imports of product p (ΔIMP pdt ), excluding those from Italy. Finally, we aggregate these growth rates across all the product-destination pairs reached by the firm in the initial year (t = 0), using as weights their share in the firm’s exports at the beginning of the period (ωipd0):

where the choice of keeping the product-destination mix constant should assure that the potential demand shock is exogenous to the firm, namely that it does not reflect product-mix adjustment over time.

Real Effective Exchange Rate (reer) This firm-specific variable is constructed as follows. First, for any destination country (d) we compute the bilateral real exchange rate as the product between the nominal exchange rate and the relative producer price index:

where an increase signals an appreciation of the real exchange rate. Second, we define the set of countries (d) served by firm i in the first year it enters the sample (t = 0). Finally, we aggregate the destination-specific real exchange rate across all the destinations reached by the firm in the initial year, using as weights their share in the firm’s exports at the beginning of the period (ωid0):

Competition From China (Chinashare) This firm-specific measure is constructed combining information on the firm’s product-mix and China’s global market share in the following way. First, for each product and year we use the CEPII-BACI dataset to compute China’s world market share, namely the value of China’s exports as a fraction of world exports, for that product (Chinashare p,t ). Second, we observe the firm-level product-mix (Pi0) in the first year the firm enters the sample (t = 0), irrespective of the destination of its exports. Finally, we aggregate the values of China’s market share across all the products included in P i0 , using as weights the composition across products of the firm’s exports observed at the beginning of the period (ωp0):

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bugamelli, M., Fabiani, S., Federico, S. et al. Back on Track? A Macro–Micro Narrative of Italian Exports. Ital Econ J 4, 1–31 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-018-0072-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-018-0072-8